A No Go For Me

Of course, if I was unemployed, or actively looking for a new job, I would have replied differently to the solicitation. Wouldn’t you have?

Grow And Fix

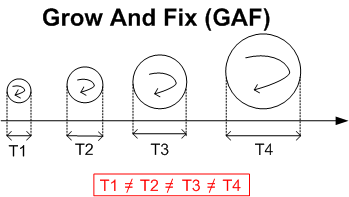

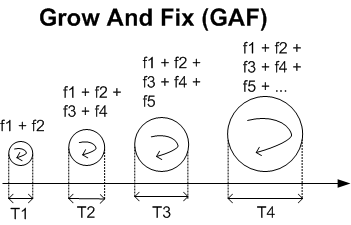

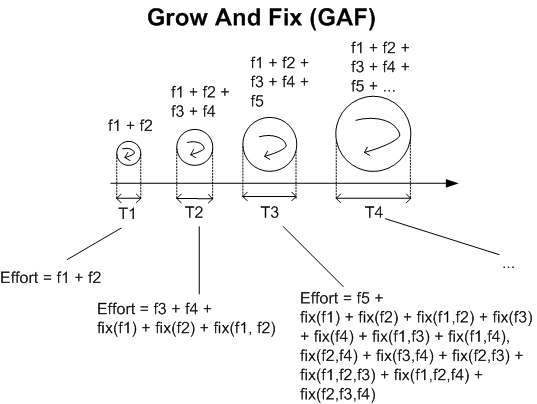

The figure below shows a series of “Grow And Fix” (GAF) cycles that models a software development effort. The gaps between each cycle represent external (to the team) deployment/usage/feedback periods. In practice, there usually are no gaps. After all, any upstanding org filled with managers who are paid to obsess over efficiency can’t allow for any idle machines between incremental releases.

Note that in the GAF way of doing things, the duration for producing a stand-alone increment varies from increment to increment. That’s because the GAF community thinks the act of arbitrarily setting T1 == T2 == T3 == T4 == T (like, say, T == 30 days) for every major increment is a pretty much stupid and dogmatic policy. As stated in the 16 page GAF user guide, the duration for each release is proportional to the breadth and depth of the functionality (f1, f2…. fx) allocated to the release.

In addition to the effort required for defining, creating and integrating new functionality into the growing system, the GAF method takes into account the effort required to “unbreak” existing functionality and to handle emergent, unexpected, behaviors that arise from function-to-function interactions (fix(f1,f2), fix(f1,f3)…).

For more detailed information on the groundbreaking new GAF methodology, including real success stories, endorsements, certification costs, books, T-shirts, hoodies, mugs, and upcoming community conferences, visit the GAF website. Enter the code BD00 at checkout to receive a 10% discount and free shipping on your first purchase.

Why “Agile” and especially Scrum are terrible

In six years of blogging, I’ve never reblogged a post… until now. I don’t agree with every point made in this insightful rant, and I outright disagree with several of them, but I resonate with many of the others via direct personal experience.

Follow-up post: here

It’s probably not a secret that I dislike the “Agile” fad that has infested programming. One of the worst varieties of it, Scrum, is a nightmare that I’ve seen actually kill companies. By “kill” I don’t mean “the culture wasn’t as good afterward”; I mean a drop in the stock’s value of more than 85 percent. This shit is toxic and it needs to die yesterday. For those unfamiliar, let’s first define our terms. Then I’ll get into why this stuff is terrible and often detrimental to actual agility. Then I’ll discuss a single, temporary use case under which “Agile” development actually is a good idea, and from there explain why it is so harmful as a permanent arrangement.

So what is Agile?

The “Agile” fad grew up in web consulting, where it had a certain amount of value: when dealing with finicky clients who don’t…

View original post 3,303 more words

Holier Than Thou

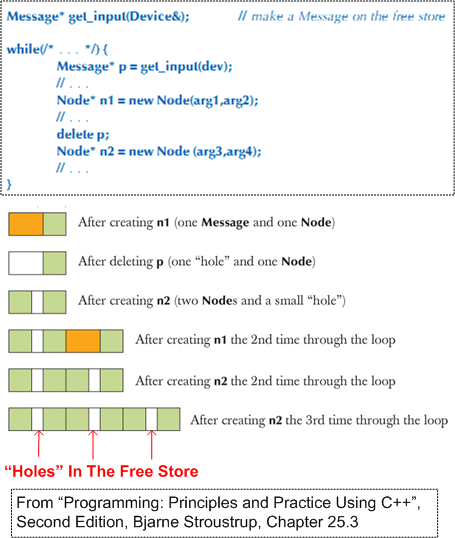

Since C++ (by deliberate design) does not include a native garbage collector or memory compactor, programs that perform dynamic memory allocation and de-allocation (via explicit or implicit use of the “new” and “delete” operators) cause small “holes” to accumulate in the free store over time. I guess you can say that C++ is “holier than thou“. 😦  Mind you, drilling holes in the free store is not the same as leaking memory. A memory leak is a programming bug that needs to be squashed. A fragmented free store is a “feature“. His holiness can become an issue only for loooong running C++ programs and/or programs that run on hardware with small RAM footprints. For those types of niche systems, the best, and perhaps only, practical options available for preventing any holes from accumulating in your briefs are to eliminate all deletes from the code:

Mind you, drilling holes in the free store is not the same as leaking memory. A memory leak is a programming bug that needs to be squashed. A fragmented free store is a “feature“. His holiness can become an issue only for loooong running C++ programs and/or programs that run on hardware with small RAM footprints. For those types of niche systems, the best, and perhaps only, practical options available for preventing any holes from accumulating in your briefs are to eliminate all deletes from the code:

- Perform all of your dynamic memory allocations at once, during program initialization (global data – D’oh!), and only utilize the CPU stack during runtime for object creation/destruction.

- If your application inherently requires post-initialization dynamic memory usage, then use pre-allocated, fixed size, unfragmentable, pools and stacks to acquire/release data buffers during runtime.

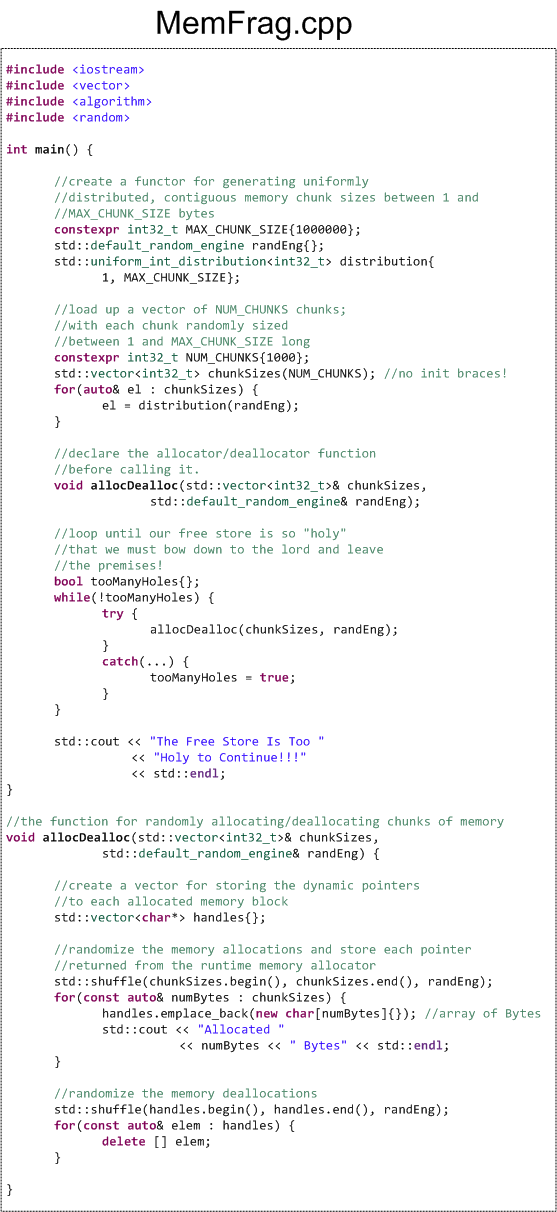

If your system maps into the “holes can freakin’ kill someone” category and you don’t bake those precautions into your software design, then the C++ runtime may toss a big, bad-ass, std::bad_alloc exception into your punch bowl and crash your party if it can’t find a contiguous memory block big enough for your impending new request. For large software systems, refactoring the design to mitigate the risk of a fragmented free store after it’s been coded/tested falls squarely into the expensive and ominous “stuff that’s hard to change” camp. And by saying “stuff that’s hard to change“, I mean that it may be expensive, time consuming, and technically risky to reweave your basket (case). In an attempt to verify that the accumulation of free store holes will indeed crash a program, I wrote this hole-drilling simulator:  Each time through the while loop, the code randomly allocates and deallocates 1000 chunks of memory. Each chunk is comprised of a random number of bytes between 1 and 1MB. Thus, the absolute maximum amount of memory that can be allocated/deallocated during each pass through the loop is 1 GB – half of the 2 GB RAM configured on the linux virtual box I am currently running the code on. The hole-drilling simulator has been running for days – at least 5 straight. I’m patiently waiting for it to exit – and hopefully when it does so, it does so gracefully. Do you know how I can change the code to speed up the time to exit?

Each time through the while loop, the code randomly allocates and deallocates 1000 chunks of memory. Each chunk is comprised of a random number of bytes between 1 and 1MB. Thus, the absolute maximum amount of memory that can be allocated/deallocated during each pass through the loop is 1 GB – half of the 2 GB RAM configured on the linux virtual box I am currently running the code on. The hole-drilling simulator has been running for days – at least 5 straight. I’m patiently waiting for it to exit – and hopefully when it does so, it does so gracefully. Do you know how I can change the code to speed up the time to exit?

Note1: This post doesn’t hold a candle to Bjarne Stroustrup’s thorough explanation of the “holiness” topic in chapter 25 of “Programming: Principles and Practice Using C++, Second Edition“. If you’re a C++ programmer (beginner, intermediate, or advanced) and you haven’t read that book cover-to-cover, then… you should.

Note2: For those of you who would like to run/improve the hole-drilling simulator, here is the non-.png source code listing:

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

int main() {

//create a functor for generating uniformly

//distributed, contiguous memory chunk sizes between 1 and

//MAX_CHUNK_SIZE bytes

constexpr int32_t MAX_CHUNK_SIZE{1000000};

std::default_random_engine randEng{};

std::uniform_int_distribution distribution{

1, MAX_CHUNK_SIZE};

//load up a vector of NUM_CHUNKS chunks;

//with each chunk randomly sized

//between 1 and MAX_CHUNK_SIZE long

constexpr int32_t NUM_CHUNKS{1000};

std::vector chunkSizes(NUM_CHUNKS); //no init braces!

for(auto& el : chunkSizes) {

el = distribution(randEng);

}

//declare the allocator/deallocator function

//before calling it.

void allocDealloc(std::vector& chunkSizes,

std::default_random_engine& randEng);

//loop until our free store is so "holy"

//that we must bow down to the lord and leave

//the premises!

bool tooManyHoles{};

while(!tooManyHoles) {

try {

allocDealloc(chunkSizes, randEng);

}

catch(const std::bad_alloc&) {

tooManyHoles = true;

}

}

std::cout << "The Free Store Is Too "

<< "Holy to Continue!!!"

<< std::endl;

}

//the function for randomly allocating/deallocating chunks of memory

void allocDealloc(std::vector& chunkSizes,

std::default_random_engine& randEng) {

//create a vector for storing the dynamic pointers

//to each allocated memory block

std::vector<char*> handles{};

//randomize the memory allocations and store each pointer

//returned from the runtime memory allocator

std::shuffle(chunkSizes.begin(), chunkSizes.end(), randEng);

for(const auto& numBytes : chunkSizes) {

handles.emplace_back(new char[numBytes]{}); //array of Bytes

std::cout << "Allocated "

<< numBytes << " Bytes" << std::endl;

}

//randomize the memory deallocations

std::shuffle(handles.begin(), handles.end(), randEng);

for(const auto& elem : handles) {

delete [] elem;

}

}

If you do copy/paste/change the code, please let me know what you did and what you discovered in the process.

Note3: I have an intense love/hate relationship with the C++ posts that I write. I love them because they attract the most traffic into this gawd-forsaken site and I always learn something new about the language when I compose them. I hate my C++ posts because they take for-freakin’-ever to write. The number of create/reflect/correct iterations I execute for a C++ post prior to queuing it up for publication always dwarfs the number of mental iterations I perform for a non-C++ post.

The Same Script, A Different Actor

A huge, lumbering dinosaur wakes up, looks in the mirror and sez: “WTF! Look how ugly and immobile I am!“. After pondering its predicament for a few moments, Mr. Dino has an epiphany: “All I gotta do is go on a diet and get a makeover!“.  It’s the same old, same old, script:

It’s the same old, same old, script:

- A large company’s performance deteriorates over time because of increasing bureaucracy, apathy, and inertia.

- Wall St. goes nutz, pressuring the company to take action.

- A new, know-it-all, executive with a successful track record is hired on to improve performance.

- The nouveau executive mandates sweeping, across-the-board, changes in the way people work without consulting the people who do the work.

- The exec makes the rounds in the press, espousing how he’s gonna make the company great again.

- After all the hoopla is gone, the massive change effort flounders and all is forgotten – it’s back to the status quo.

The latest incarnation of this well worn tale seems to describe what’s happening in the IT department at longtime IT stalwart, IBM: IBM CIO Designs New IT Workflow for Tech Giant Under Pressure. We’ve heard this all before (Nokia, Research In Motion, Sun, etc):

The mission is to have innovation and the speed of small companies .. and see if we can do that at scale – IBM Corp. CIO Jeff Smith

I’ll give you one guess at to what Mr. Smith’s turnaround strategy is…

Give up? It’s, of course, “Large Scale, Distributed, Agile Development“.

I can see all the LeSS (Large Scale Scrum) and SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework) consultants salivating over all the moolah they can suck out of IBM. Gotta give ’em credit for anticipating the new market for “scaling Agile” and setting up shop to reap the rewards from struggling, deep-pocketed, behemoths like IBM.

It’s ironic that IBM wants to go Agile, yet a part of their business is (was?) to provide Agile consulting expertise to other companies. In fact, one of their former Agile consultant employees, Scott Ambler, invented his own Agile processes: Agile Unified Process (AUP) and Disciplined Agile Delivery (DAD). On top of that, look who wrote this:

Obviously, not all massive turnaround efforts fail. In fact, IBM did an about face once before under the leadership of, unbelievably, a former Nabisco cookie executive named Lou Gerstner. I like IBM. I hope they deviate from the script and return to greatness once again.

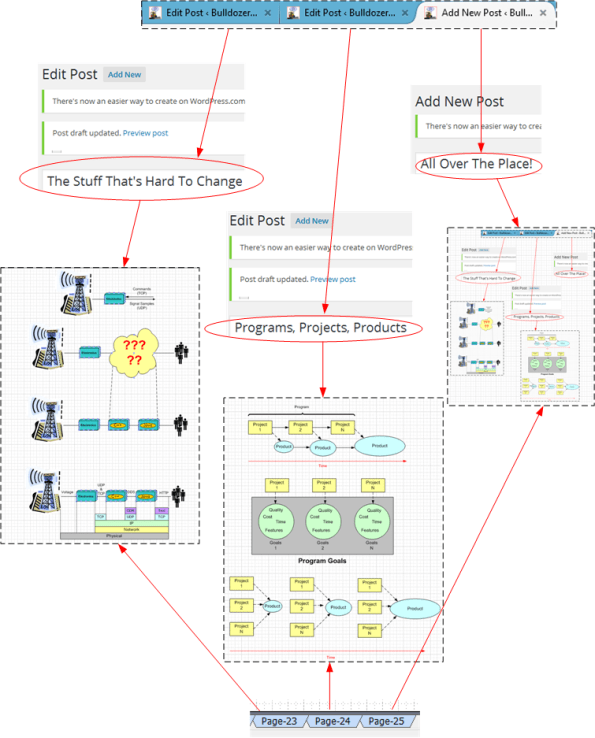

A Semi-Organized Mess

I don’t know when this post will be published, but I started writing it at 6:13 AM on Saturday, May 16, 2015. I had woken up at 4:00 AM (which is usual for me) and started drafting a blog post that’s currently titled “The Stuff That’s Hard To Change“. Then, whilst in the midst of crafting that post, a partially formed idea popped into my head for another post. So I:

- pushed the first idea aside,

- executed a mental context switch, and

- started writing the second post (which is currently titled “Programs, Projects, Products“).

Whilst writing the second post, yet another idea for a third post (the one you’re currently reading) came to mind. So, yet again, I spontaneously performed a mental context switch and started writing this post. Sensing that something was amiss, I stepped back and found myself… thrashing all over the freakin’ place!

In case you’re wondering what my browser and visio tabs looked like during my maniacal, mutli-tasking, fiasco, here’s a peek into the semi-organized mess that was churning in my mind at the time:

Thankfully, I don’t enter a frenzied, ADHD, writing state that often. Because of my training as a software engineer and the meticulous thinking style required to write code, I’m usually a very focused, single-tasking, person – sometimes too focused, and oblivious to what’s happening outside of my head.

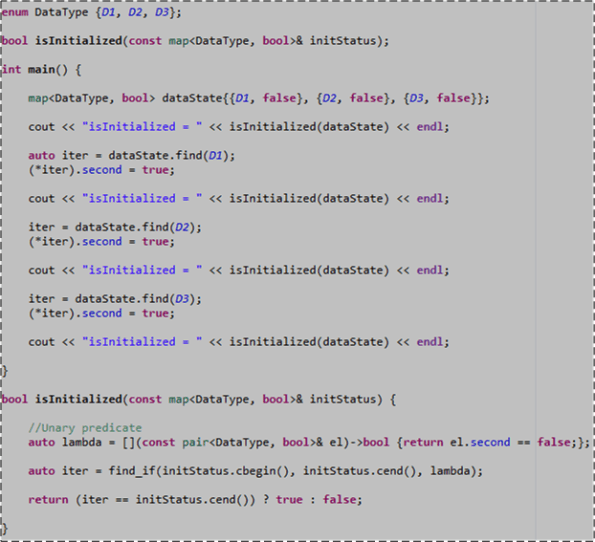

Oh, I almost forgot, but the act of writing the previous paragraph reminded me. I squeezed in a fourth task during my 4:00 AM to 6:00 AM stint at my computer. I prototyped a C++ function that I knew I needed to use at work soon:

I actually wrote that code first, prior to entering my thrashful writing state. And, in extreme contrast to my blogging episode, I wrote the code in a series of focused, iterative, write/test/fix, feedback loops. There was no high speed context-switching involved. It’s strange how the mind works.

The mind is like a box of chocolates. Ya never know what you’re gonna get.

Acting In C++

Because they’re a perfect fit for mega-core processors and they’re safer and more enjoyable to program than raw, multi-threaded, systems, I’ve been a fan of Actor-based concurrent systems ever since I experimented with Erlang and Akka (via its Java API). Thus, as a C++ programmer, I was excited to discover the “C++ Actor Framework” (CAF). Like the Akka toolkit/runtime, the CAF is based on the design of the longest living, proven, production-ready, pragmatic, actor-based, language that I know of – the venerable Erlang programming language.

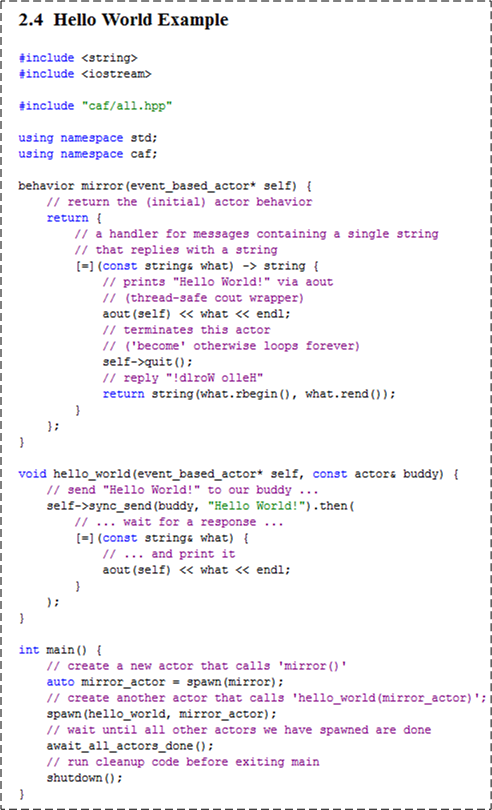

Curious to check out the CAF, I downloaded, compiled, and installed the framework source code with nary a problem (on CentOS 7.0, GCC 4.8.2). I then built and ran the sample “Hello World” program presented in the user manual:

As you can see, the CAF depends on the use one of my favorite C++11 features – lambda functions – to implement actor behavior.

The logic in main() uses the CAF spawn() function to create two concurrently running, message-exchanging (messages of type std::string), actors named “mirror” and “hello_world“. During the spawning of the “hello_world” actor, the main() logic passes it a handle (via const actor&) to the previously created “mirror” actor so that “hello_world” can asynchronously communicate with “mirror” via message-passing. Then, much like the parent thread in a multi-threaded program “join()“s the threads it creates to wait for the threads to complete their work, the main() thread of control uses the CAF await_all_actors_done() function to do the same for the two actors it spawns.

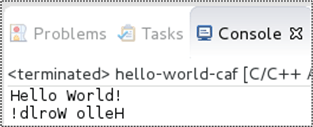

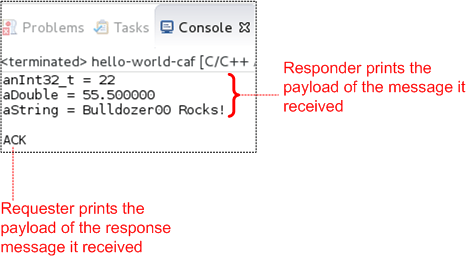

When I ran the program as a local C++ application in the Eclipse IDE, here is the output that appeared in the console window:

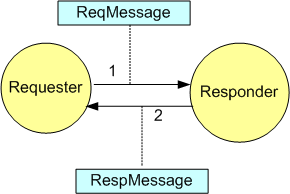

The figure below visually illustrates the exchange of messages between the program’s actors during runtime. Upon being created, the “hello_world” actor sends a text message (via sync_send()) containing “Hello World” as its payload to the previously spawned “mirror” actor. The “hello_world” actor then immediately chains the then() function to the call to synchronously await for the response message it expects back from the “mirror” actor. Note that a lambda function that will receive and print the response message string to the console (via the framework’s thread-safe aout object) is passed as an argument into the then() function.

Looking at the code for the “mirror” actor, we can deduce that when the framework spawns an instance of it, the framework gives the actor a handle to itself and the actor returns the behavior (again, in the form of a lambda function) that it wants the framework to invoke each time a message is sent to the actor. The “mirror” actor behavior: prints the received message to the console, tells the framework that it wants to terminate itself (via the call to quit()), and returns a mirrored translation of the input message to the framework for passage back to the sending actor (in this case, the “hello_world” actor).

Note that the application contains no explicit code for threads, tasks, mutexes, locks, atomics, condition variables, promises, futures, or thread-safe containers to futz with. The CAF framework hides all the underlying synchronization and message passing minutiae under the abstractions it provides so that the programmer can concentrate on the application domain functionality. Great stuff!

I modified the code slightly so that the application actors exchange user-defined message types instead of std::strings.

Here is the modified code:

struct ReqMessage {

int32_t anInt32_t;

double aDouble;

string aString;

};

struct RespMessage {

enum class AckNack{ACK, NACK};

AckNack response;

};

void printMsg(event_based_actor* self, const ReqMessage& msg) {

aout(self) << "anInt32_t = " << msg.anInt32_t << endl

<< "aDouble = " << msg.aDouble << endl

<< "aString = " << msg.aString << endl

<< endl;

}

void fillReqMessage(ReqMessage& msg) {

msg.aDouble = 55.5;

msg.anInt32_t = 22;

msg.aString = "Bulldozer00 Rocks!";

}

behavior responder(event_based_actor* self) {

// return the (initial) actor behavior

return {

// a handler for messages of type ReqMessage

// and replies with a RespMessage

[=](const ReqMessage& msg) -> RespMessage {

// prints the content of ReqMessage via aout

// (thread-safe cout wrapper)

printMsg(self, msg);

// terminates this actor *after* the return statement

// ('become' a quitter, otherwise loops forever)

self->quit();

// reply with an "ACK"

return RespMessage{RespMessage::AckNack::ACK};

}};

}

void requester(event_based_actor* self, const actor& responder) {

// create & send a ReqMessage to our buddy ...

ReqMessage req{};

fillReqMessage(req);

self->sync_send(responder, req).then(

// ... wait for a response ...

[=](const RespMessage& resp) {

// ... and print it

RespMessage::AckNack payload{resp.response};

string txt =

(payload == RespMessage::AckNack::ACK) ? "ACK" : "NACK";

aout(self) << txt << endl;

});

}

int main() {

// create a new actor that calls 'responder()'

auto responder_actor = spawn(responder);

// create another actor that calls 'requester(responder_actor)';

spawn(requester, responder_actor);

// wait until all other actors we have spawned are done

await_all_actors_done();

// run cleanup code before exiting main

shutdown();

}

Whence Actors?

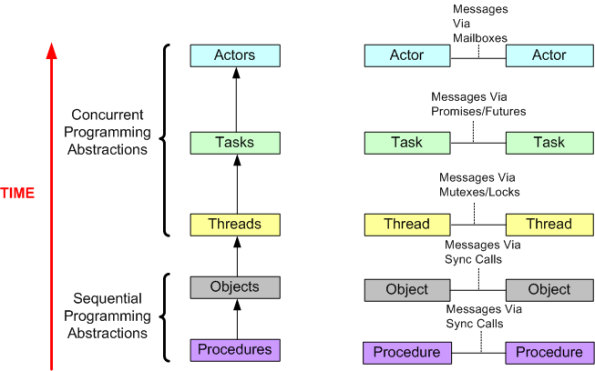

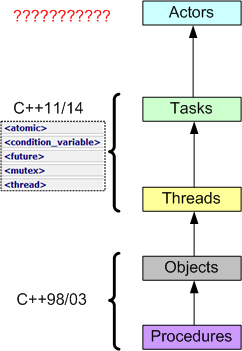

While sketching out the following drawing, I was thinking about the migration from sequential to concurrent programming driven by the rise of multicore machines. Can you find anything wrong with it?

Right out of the box, C++ provided Objects (via classes) and procedures (via free standing functions). With C++11, standardized support for threads and tasks finally arrived to the language in library form. I can’t wait for Actors to appear in….. ?

It’s All About That Jell

Agile, Traditional, Lean, Burndown Charts, Kanban Boards, Earned Value Management Metrics, Code Coverage, Static Code Analysis, Coaches, Consultants, Daily Standup Meetings, Weekly Sit Down Meetings, Periodic Program/Project Reviews. All the shit managers obsess over doesn’t matter. It’s all about that Jell, ’bout that jell, ’bout that jell.