Archive

The Undiscussable Issues Of Code Reviews

Everyone and their brother, including BD00, thinks source code inspections are a best practice for detecting and eliminating defects before they burrow into your code to wreak havoc during expensive, downstream debugging debacles. There are reams of study data to support the efficiency of code reviews (relative to testing) in the battle of the bug. But, the world being as messy as it is, there’s a fly in the ointment. That fly is the cost required to, and this is important, “effectively” execute code reviews:

“And yet, at somewhere around 100 lines of code inspected per hour, it takes an investment of many hours to inspect even the smallest piece of software, say a couple of thousand of lines of code.” – Facts And Fallacies Of SW Engineering, Robert Glass, P106

“There’s a sweet spot around 150 lines per hour that detects most of the bugs you’re going to find.” – The Art Of Designing Embedded Systems, Jack Gannsle, P21

Given these metrics, let’s concoct a concrete example so we can further investigate the cost issue :

Assuming the simple math is correct, the project manager in this example should “explicitly” allocate $200K and 4 calendar months of effort somewhere in his/her micro-managed Microsoft Project plan for our 100K line program, no?

The question is, when was the last time you saw a project plan that transparently and explicitly enumerated the time and cost for performing those code reviews mandated by your CMMI L3+ compliant process? If you haven’t seen such a plan, find out what kind of blowback you get from asking to have the resources required for “effective” code reviews embedded in your current or next prescriptive project plan. For even more drama, ask your QA group if there are any metrics (bugs found/review-hour, bug densities) that indicate how effective your code reviews are.

Since we’re having fun here, let’s go a little deeper into this undiscussable underworld by examining these two assumptions from our fabricated example:

- The reviewers are qualified and readily available: they understand the programming language(s) the code is written in; they have memorized the 200 page home-grown coding standards manual(s); they understand and have memorized the functional requirements the code is supposed to implement.

- The reviews are synchronized; the reviewers all start and end the code review at the same time.

Are these assumptions realistic? If not, then how do the budget and schedule numbers get affected?

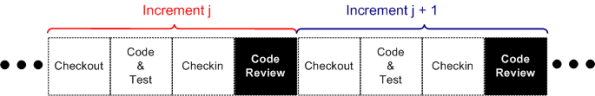

Finally, in an iterative and incremental development process, when should code reviews take place? Piece-meal and disruptively after checking in each increment’s unit-tested code? In one big, formal she-bang after all the unit tests have passed?

How do you do code reviews, and how effective are they?

A Stone Cold Money Loser

A widespread and unquestioned assumption deeply entrenched within the software industry is:

For large, long-lived, computationally-dense, high-performance systems, this attitude is a stone cold money loser. When the original cast of players has been long departed, and with hundreds of thousands (perhaps millions) of lines of code to scour, how cost-effective and time-effective do you think it is to hurl a bunch of overpaid programmers and domain analysts at a logical or numerical bug nestled deeply within your golden goose. What about an infrastructure latency bug? A throughput bug? A fault-intolerance bug? A timing bug?

Everybody knows the answer, but no one, from the penthouse down to the boiler room wants to do anything about it:

To lessen the pain, note that to be “kind” (shhh! Don’t tell anyone) BD00 used the less offensive “artifacts” word – not the hated “D” word. And no, I don’t mean huge piles of detailed, out-of-synch, paper that would torch your state if ignited. And no, I don’t mean sophisticated-looking, semantic-less garbage spit out by domain-agnostic tools “after” the code is written.

Wah, wah, wah:

- “But it’s impossible to keep the artifacts in synch with the code” – No, it’s not.

- “But no one reads artifacts” – Then make the artifacts readable.

- “But no one knows how to write good artifacts” – Then teach them.

- “But no one wants to write artifacts” – So, what’s your point? This is a business, not a vacation resort.

Not Either, But Both?

I recently dug up an old DDS tutorial pitch by distributed system middleware expert extraordinaire, Doug Schmidt. The last slide in the pitch shows a side-by-side, high-level feature comparison of CORBA and DDS:

High performance middleware technologies like CORBA and DDS are big, necessarily complex beasts that have high learning curves. Thus, I’m not so sure I agree with Doug’s assessment that complex software systems (like sensor-based command and control systems) need both. One can build a pub-sub mechanism on top of CORBA (using the notification, event, or messaging services) and one can build a client-server, request-response mechanism on top of DDS (using the TCP/IP-like “reliability” QoS). What do you think about the tradeoff? Fill the holes yourself with a tad of home-grown infrastructure code, or use both and create a two-headed, fire-breathing dragon?

The Org Is The Product

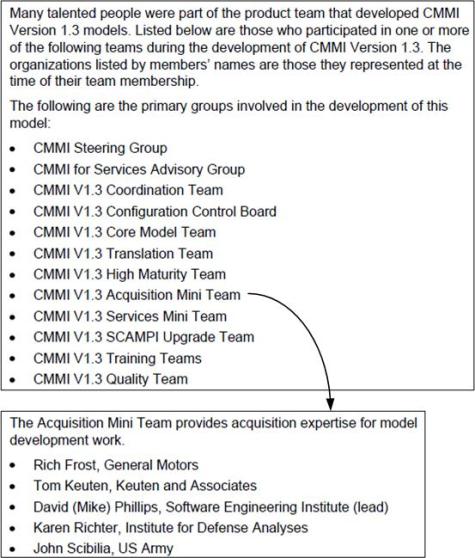

Someone once said something like: “the products an organization produces mirror the type of organization that produces them“. Thus, a highly formal, heavyweight, bureaucratic, title-obsessed, siloed, and rigid org will most likely produce products of the same ilk.

With this in mind, let’s look at the US DoD funded Software Engineering Institute (SEI) and one of its flagship products: the “CMMI® for Development, Version 1.3“. The snippet below was plucked right out of the 482 page technical report that defines the CMMI-DEV:

So, given no other organizational information other than that provided above, what kind of product would you speculate the CMMI-DEV is? Of course, like BD00 always is, you’d be dead wrong if you concluded that the CMMI-DEV is a highly formal, heavyweight, bureaucratic, title-obsessed, siloed, and rigid model for product development.

Firefighter Fran

Being anointed as a firefighter in an org that’s constantly battling blazes is one of the highest callings there is for any group member not occupying a coveted slot in the chief’s inner circle. Hell, since you didn’t start the fire and you’re gonna try your best to save the lot from a financial disaster, it’s a can’t-lose situation. If you fail, you’ll be patted on the back with a “nice try soldier; now we’re gonna go find the firestarter and kick his arse to kingdom come”. If you extinguish the blaze, at least you’ll lock in that 2% raise for this fiscal year. You might even get an accompanying $25 Dunkin Donuts gift card to keep your spare tire inflated with dozens of delectable, confectionary delights.

Given the above context, let’s start this heart-warming story off with you in the glorious role of firefighter Fran. You, my dear Fanny, oops, I mean Franny, have been assigned to put out a major blaze in one of your flagship legacy software products before it spreads to one of the nearby money silos and blows it sky high. Time, as always, is of the utmost importance. D’oh!

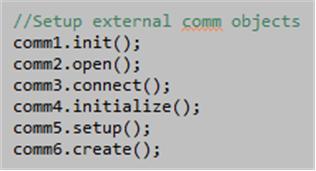

Since the burning pile of poop’s “agile” architecture and design documentation is a bunch of fluffy camouflage created solely to satisfy some process compliance checklist, you check out the code base and directly fire up vi (IDEs are for new age pussies!) for some serious sleuthing.

After glancing at the source tree‘s folder structure and concluding that it’s an incomprehensible, acronym-laden quagmire, you take the random plunge. With fingers a tremblin’ and fire hose a danglin’, you open up one of the 5000 source code files that’s postfixed with the word “Main“. You then start sequentially reading some hieroglyphics that’s supposed to be source code and you come to an abrupt halt when you see this:

And… that’s it! The story pauses here because BD00’s lizard brain is about to explode and it’s your turn to provide some “collaborative“, creative input.

So, what does our guaranteed-to-be-hero, fireman Fran, do next? Does the fire get doused? Does the pecuniary silo explode? Is the firestarter ever found? Does Fanny get the DD gift card? If so, how many crullers and donut holes does he scarf down?

Who knows, maybe you can become a self-proclaimed l’artiste like BD00 too, no?

Too Detailed, Too Fast

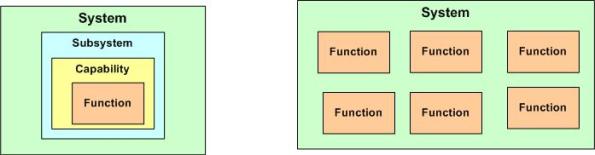

One of the dangers system designers continually face is diving into too much detail, too fast. Given a system problem statement, the tendency is to jump right into fine-grained function (feature) definitions so that the implementation can get staffed and started pronto. Chop-chop, aren’t you done yet?

The danger in bypassing a multi-leveled analysis/synthesis effort and directly mapping the problem elements into concrete, buildable functions is that important, unseen, higher level relationships can be missed – and you may pay the price for your haste with massive downstream rework and integration problems. Of course, if the system you’re building is simple enough or you’re adding on to an existing system, then the skip level approach may work out just fine.

Irritated

Unsurprisingly, one of BD00’s posts irritated a reader who stumbled upon it. For some strange reason, BD00’s scribblings have that effect on some people. In the irritating post, “The Old Is New Again“, BD00 referred to Data and Control Flow diagrams as “old and obsolete“. In caustic BD00 fashion, the reader commented:

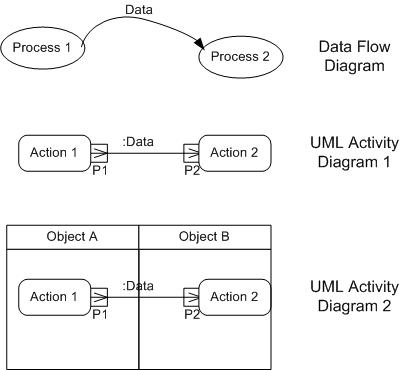

Use Cases and Activity Diagrams, in contrast (to the Data Flow diagram), offer little guidance in effective partitioning. They rely upon the age old “sledge hammer” approach to partitioning” (ie, just break-er-up any way you can). Sledge hammer partitioning is what cave men used to partition entities. So in a critical sense, DFD’s are new and hip, while Use Cases and Activity Diagrams are based upon logic that is older than dirt.

BD00 likes all visual modeling tools – including the DFD hatched during the heyday of structured analysis. BD00 only meant “old and obsolete” in the sense that DFDs pre-dated the arrival of the UML and the object-oriented approach to system analysis and design. However, BD00 did feel the need to correct the reader’s misunderstanding of the features and capabilities that UML Activity Diagrams offer up to analysts/designers.

Both the DFD and UML activity diagram pair below equivalently capture an analyst’s partitioning design decision (where DFD Process X == Activity Diagram Action X). Via “swimlanes“, the lower activity diagram makes the result of a second design decision visible: the conscious allocation of the Actions to the higher level Objects that will perform them during system operation. So, how are UML activity diagrams inferior to DFDs in supporting partitioning? A rich palette of other symbols (forks, joins, decisions, merges, control flows, signals) are also available to analysts (if needed) for capturing design decisions and exposing them for scrutiny.

DFDs and UML diagrams are just tools – job performance aids. Learning how to use them, and learning how to use them effectively, are two separate challenges. Design “guidance” for system partitioning, leveling, balancing, etc, has to come from somewhere else. From a mentor? From personal experience learning how to design systems over time? From divine intervention?

You May Be Wrong

With the frequency and ferocity of attacks BD00 foists upon the guild of institutional management in this highfalutin blog, you might think BD00 is a miserably unhappy and vengeful malcontent at work. If you do, then you’d be wrong. BD00 knows for a fact that his boss’s boss reads this blog “religiously“. BD00 also knows that his company’s CEO has stopped by to sample the waters at least once. The CEO even discretely and unjudgmentally referenced an idea from this caustic blog in a large gathering (for which he received a free BD00 T-shirt).

Do one thing every day that scares you. – Baz Luhrmann (Everybody’s Free To Wear Sunscreen)

In three-plus years of blogging, BD00 has never received a peek-a-boo visit or been directly rebuked or threatened by anyone in his company’s leadership chain for exposing his wacko, close-to-home thoughts in writing. If you wrote a similar, self-exposing blog, could you confidently say the same about your management ?

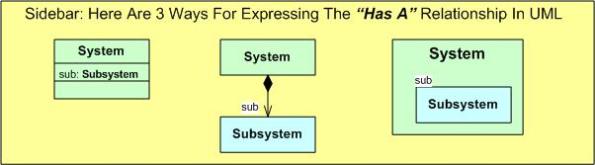

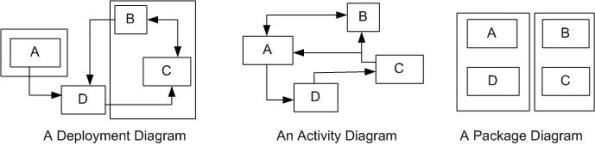

Broken, Not Bent

It’s one thing to “bend” the UML to express a design concept that you don’t know how to express with the language, but it’s another thing to “break” it outright. By “break“, I mean drawing old-school, ad-hoc, single-symbol diagrams that all look alike and passing them off as UML class, deployment, activity, etc, diagrams.

By propagating broken UML diagrams out into the world in a sincere, but fruitless, attempt to establish a shared understanding among team members, the exact opposite can occur – mass confusion and an error prone, friction-filled development effort. Even worse, presenting the ad-hoc quagmire to customers and financiers who have a rudimentary education in object orientation and UML can cause them to question the competence of the presenters and the wisdom of their investment choice.

But hey, there’s nothing to worry about. Nobody understands or cares about the UML anyway. Thus, the ambiguity, inconsistency, and conflicts inherent in the design won’t be exposed (or ever traced-back-to) if schedule and cost disaster strikes.

All models are wrong. Some, however, are useful. – George E. Box

Related articles

- Proprietary Extensions (bulldozer00.com)

- UML Tool for Fast UML Diagrams (allincircles.wordpress.com)

- Mind Maps: The Poor Man’s Design Tool (drdobbs.com)

Scrum And Non-Scrum Interfaces

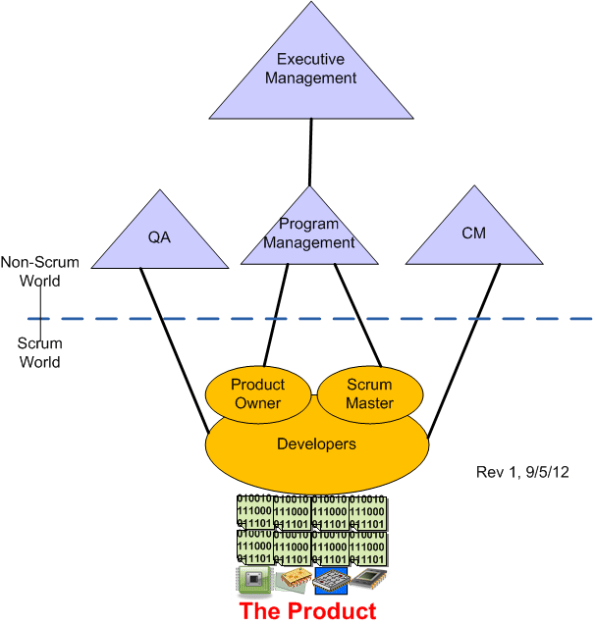

According to the short and sweet Schwaber/Sutherland Scrum Guide, a Scrum team is comprised of three, and only three, simple roles: the Product Owner, the Scrum Master, and the Developers. One way of “interfacing” a flat and collaborative Scrum team to the rest of a traditional hierarchical organization is shown below. The fewer and thinner the connections, the less impedance mismatch and the greater the chances of efficient success.

Regarding an ensemble of Scrum Developers, the guide states:

Scrum recognizes no titles for Development Team members other than Developer, regardless of the work being performed by the person; there are no exceptions to this rule.

I think (but am not sure) that the unambiguous “no exceptions” clause is intended to facilitate consensus-based decision-making and preclude traditional “titled” roles from making all of the important decisions.

So, what if your conservative org is willing to give Scrum an honest, spirited, try but it requires the traditional role of “lead(s)” on teams? If so, then from a pedantic point of view, the model below violates the “no exceptions” rule, no? But does it really matter? Should Scrum be rigidly followed to the letter of the law? If so, doesn”t that demand go against the grain of the agile philosophy? When does Scrum become “Scrum-but“, and who decides?

Related articles

- The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (bulldozer00.com)

- Bring Back The Old (bulldozer00.com)

- Ultimately And Unsurprisingly (bulldozer00.com)

- From Complexity To Simplicity (bulldozer00.com)

- Why I’m done with Scrum (lostechies.com)