Archive

Spike To Learn

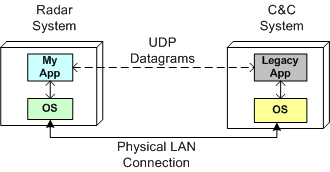

As one of the responsibilities on my last project, I had to interface one of our radars to a 10+ year old, legacy, command-and-control system built by another company. My C++11 code was required to receive commands from the control system and send radar data to it via UDP datagrams over a LAN that connects the two systems together.

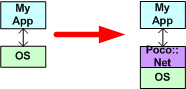

It’s unfortunate, but we won’t get a standard C++ networking library until the next version of the C++ standard gets ratified in 2017. However, instead of using the low-level C sockets API to implement the interface functionality, I chose to use the facilities of the Poco::Net library.

Poco is a portable, well written, and nicely documented set of multi-function, open source C++ libraries. Among other nice, higher level, TCP/IP and http networking functionality, Poco::Net provides a thin wrapper layer around the native OS C-language sockets API.

Since I had never used the Poco::Net API before, I decided to spike off the main trail and write a little test program to learn the API before integrating the API calls directly into my production code. I use the “Spike To Learn” best practice whenever I can.

Here is the finished and prettied-up spike program for your viewing pleasure:

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

#include "Poco/Net/SocketAddress.h"

#include "Poco/Net/DatagramSocket.h"

using Poco::Net::SocketAddress;

using Poco::Net::DatagramSocket;

int main() {

//simulate a UDP legacy app bound to port 15001

SocketAddress legacyNodeAddr{"localhost", 15001};

DatagramSocket legacyApp{legacyNodeAddr}; //create & bind

//simulate my UDP app bound to port 15002

SocketAddress myAddr{"localhost", 15002};

DatagramSocket myApp{myAddr}; //create & bind

//myApp creates & transmits a message

//encapsulated in a UDP datagram to the legacyApp

char myAppTxBuff[]{"Hello legacyApp"};

auto msgSize = sizeof(myAppTxBuff);

myApp.sendTo(myAppTxBuff,

msgSize,

legacyNodeAddr);

//legacyApp receives a message

//from myApp and prints its payload

//to the console

char legacyAppRxBuff[msgSize];

legacyApp.receiveBytes(legacyAppRxBuff, msgSize);

std::cout << std::string{legacyAppRxBuff}

<< std::endl;

//legacyApp creates & transmits a message

//to myApp

char legacyAppTxBuff[]{"Hello myApp!"};

msgSize = sizeof(legacyAppTxBuff);

legacyApp.sendTo(legacyAppTxBuff,

msgSize,

myAddr);

//myApp receives a message

//from legacyApp and prints its payload

//to the console

char myAppRxBuff[msgSize];

myApp.receiveBytes(myAppRxBuff, msgSize);

std::cout << std::string{myAppRxBuff}

<< std::endl;

}

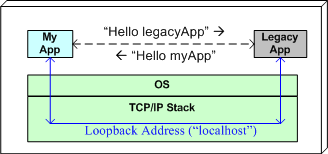

As you can see, I used the Poco::Net::SocketAddress and Poco::Net::DatagramSocket classes to simulate the bi-directional messaging between myApp and the legacyApp on one machine. The code first transmits the text message “Hello legacyApp!” from myApp to the legacyApp; and then it transmits the text message “Hello myApp!” from the legacyApp to myApp.

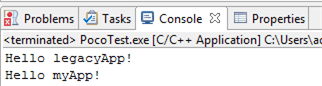

Lest you think the program doesn’t work 🙂 , here is the console output after the final compile & run cycle:

As a side note, notice that I used C++11 brace-initializers to uniformly initialize every object in the code – except for one: the msgSize object. I had to fallback and use the “=” form of initialization because “auto” does not yet play well with brace-initializers. For who knows why, the type of obj in a statement of the form “auto obj{5};” is deduced to be a std::initializer_list<T> instead of a simple int. I think this strange inconvenience will be fixed in C++17. It may have been fixed already in the recently ratified C++14 standard, but I don’t know for sure. Do you?

Ooh, The New Phone Book Is Here!

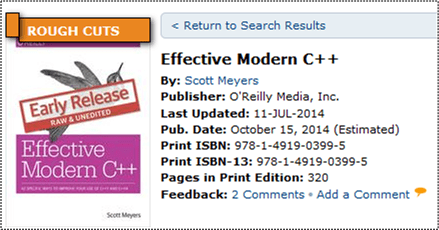

W00t! The pre-release version of Scott Meyers’ “Effective Modern C++” book is currently available to SafariBooksOnline subscribers:

In case you were wondering, here is the list of items Scott covers:

I’m currently on item number 11. What item are you on? 😛

In case you were wondering what the hell the title of this post has to do with the content of it, here’s the missing piece of illogic:

Multiple, Independent Sources Of Information On The Same Topic

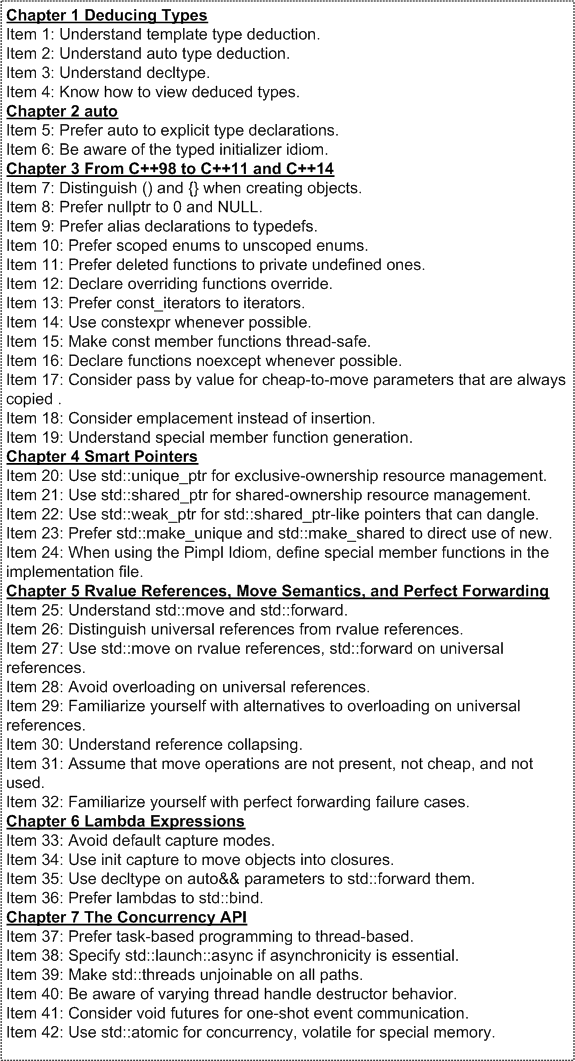

I can’t rave enough about how great a safaribooksonline.com subscription is for writing code. Take a look at this screenshot:

As you can hopefully make out, I have five Firefox tabs open to the following C++11 programming books:

- The C++ Programming Language, 4th Edition – Bjarne Stroustrup

- The C++ Standard Library: A Tutorial and Reference (2nd Edition) – Nicolai M. Josuttis

- C++ Primer Plus (6th Edition) – Stephen Prata

- C++ Primer (5th Edition) – Stanley B. Lippman, Josée Lajoie, Barbara E. Moo

- C++ Concurrency in Action: Practical Multithreading – Anthony Williams

A subscription is a bit pricey, but if you can afford it, I highly recommend buying one. You’ll not only write better code faster, you’ll amplify your learning experience by an order of magnitude from having the capability to effortlessly switch between multiple, independent sources of information on the same topic. W00t!

Game Changer

Even though I’m a huge fan of the man, I was quite skeptical when I heard Bjarne Stroustrup enunciate: “C++ feels like a new language“. Of course, Bjarne was talking about the improvements brought into the language by the C++11 standard.

Well, after writing C++11 production code for almost 2 years now (17 straight sprints to be exact), I’m no longer skeptical. I find myself writing code more fluidly, doing battle with the problem “gotchas” instead of both the problem and the language gotchas. I don’t have to veer off track to look up language technical details and easily forgotten best-practices nearly as often as I did in the pre-C++11 era.

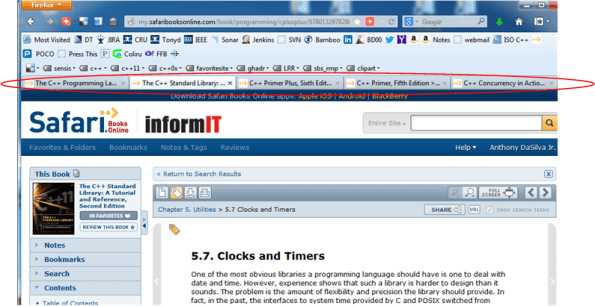

It seems that the authors of the “High Integrity C++” coding standard agree with my assessment. In a white paper summarizing the changes to their coding standard, here is what they have to say:

Even though C++’s market niche has shrunk considerably in the 21st century, it is still widely used throughout the industry. The following chart, courtesy of Scott Meyers’ recent talk at Facebook, shows that the old-timer still has legs. The pending C++14 and C++17 updates virtually guarantee its relevance far into the future; just like the venerable paper clip and spring-loaded mouse trap.

Context Sensitive Keywords

Update: Thanks to Chris’s insightful comment, the title of this post should have been “Context Sensitive Identifiers“. “override” and “final” are not C++ keywords; they are identifiers with special meaning.

If maintaining backward compatibility is important, then introducing a new keyword into a programming language is always a serious affair. Introducing a new keyword that is already used in millions of lines of existing code as an identifier (class name, namespace name, variable name, etc), can break a lot of product code and discourage people from upgrading their compilers and using the new language/library features.

Unlike other languages, backward compatibility is a “feature” (not a “meh“) in C++. Thus, the proposed introduction of a new keyword is highly scrutinized by the standards committee when core language improvements are considered. This is the main reason why the verbosity-reducing “auto” keyword wasn’t added until the C++11 standard was hatched.

Even though Bjarne Stroustrup designed/implemented “auto” in C++ over 30 years ago to provide for convenient compiler type deduction, the priority for backward compatibility with C caused it to be sh*t-canned for decades. However, since (hopefully) nobody uses it in C code anymore (“auto” is the default storage type for all C local variables – so why be redundant?), the time was deemed right to include it in the C++11 release. Of course, some really, really old C/C++ code will get broken when compiled under a new C++11 compiler, but the breakage won’t be as dire as if “auto” had made it into the earlier C++98 or C++03 standards.

With the seriousness of keyword introduction in mind, one might wonder why the “override” and “final” keywords were added to C++11. Surely, they’re so common that millions of lines of C/C++ legacy code will get broken. D’oh!

But wait! To severely limit code-breakage, the “override” and “final” keywords are defined to be context sensitive. Unless they’re used in a purposefully narrow, position-specific way, C++11 compilers will reject the source code that contains them.

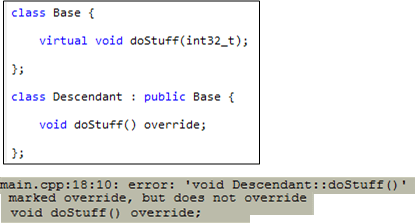

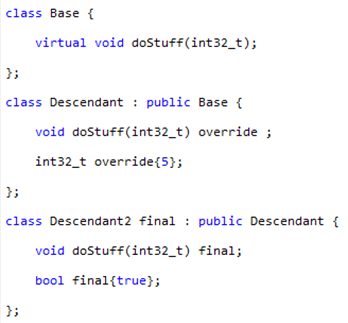

The “final” keyword (used to explicitly prevent further inheritance and/or virtual function overriding) can only be used to qualify a class definition or a virtual function declaration. The closely related “override” keyword (used to prevent careless mistakes when declaring a virtual function) can only be used to qualify a virtual function. The figure below shows how “final” and “override” clarify programmer intention and prevent accidental mistakes.

Because of the context-specific constraints imposed on the “final” and “override” keywords, this (crappy) code compiles fine:

The point of this last code fragment is to show that the introduction of context-specific keywords is highly unlikely to break existing code. And that’s a good thing.

Looks Weird, But Don’t Be Afraid To Do It

Modern C++ (C++11 and onward) eliminates many temporaries outright by supporting move semantics, which allows transferring the innards of one object directly to another object without actually performing a deep copy at all. Even better, move semantics are turned on automatically in common cases like pass-by-value and return-by-value, without the code having to do anything special at all. This gives you the convenience and code clarity of using value types, with the performance of reference types. – C++ FAQ

Before C++11, you’d have to be tripping on acid to allow a C++03 function definition like this to survive a code review:

std::vector<int> moveBigThingsOut() {

const int BIGNUM(1000000);

std::vector<int> vints;

for(int i=0; i<BIGNUM; ++i) {

vints.push_back(i);

}

return vints;

}

Because of: 1) the bolded words in the FAQ at the top of the page, 2) the fact that all C++11 STL containers are move-enabled (each has a move ctor and a move assignment member function implementation), 3) the fact that the compiler knows it is required to destruct the local vints object just before the return statement is executed, don’t be afraid to write code like that in C++11. Actually, please do so. It will stun reviewers who don’t yet know C++11 and may trigger some fun drama while you try to explain how it works. However, unless you move-enable them, don’t you dare write code like that for your own handle classes. Stick with the old C++03 pass by reference idiom:

void passBigThingsOut(std::vector<int>& vints) {

const int BIGNUM(1000000);

vints.clear();

for(int i=0; i<BIGNUM; ++i) {

vints.push_back(i);

}

}

Which C++11 user code below do you think is cleaner?

//This one-liner?

auto vints = moveBigThingsOut();

//Or this two liner?

std::vector<int> vints{};

passBigThingsOut(vints);

Move Me, Please!

UPDATE: Don’t read this post. It’s wrong, sort of 🙂 Actually, please do read it and then go read John’s comment below along with my reply to him. D’oh!

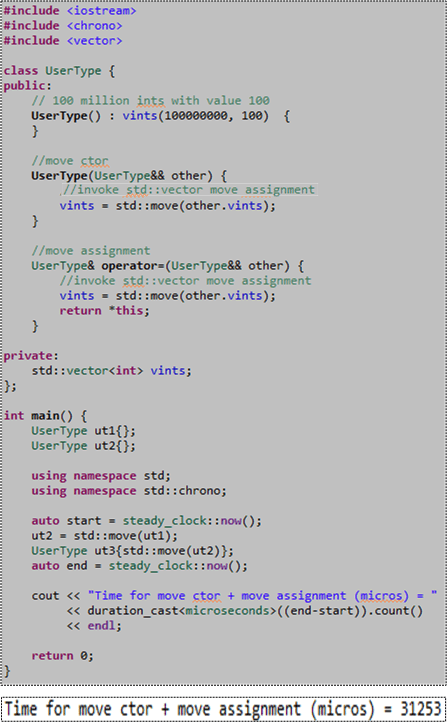

Just because all the STL containers are “move enabled” in C++11, it doesn’t mean you get their increased performance for free when you use them as member variables in your own classes. You don’t. You still have to write your own “move” constructor and “move” assignment functions to obtain the superior performance provided by the STL containers. To illustrate my point, consider the code and associated console output for a typical run of that code below.

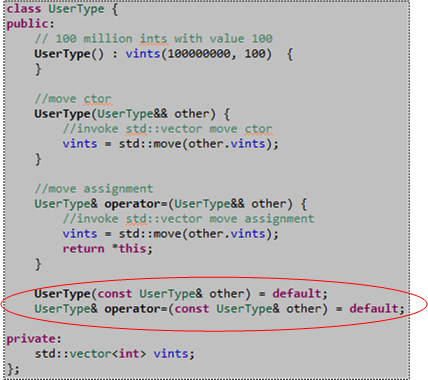

Please note the 3o-ish millisecond performance measurement we’ll address later in this post. Also note that since only the “move” operations are defined for the UserType class, if you attempt to “copy” construct or “copy” assign a UserType object, the compiler will barf on you (because in this case the compiler doesn’t auto-generate those member functions for you):

However, if you simply add “default” declarations of the copy ctor and copy assignment operations to the UserType class definition, the compiler will indeed generate their definitions for you and the above code will compile cleanly:

Ok, now remember that 30-ish millisecond performance metric we measured for “move” performance? Let’s compare that number to the performance of a “copy” construct plus “copy” assign pair of operations by adding this code to our main() function just before the return statement:

After compiling and running the code that now measures both “move” and “copy” performance, here’s the result of a typical run:

As expected, we measured a big boost in performance, 5X in this case, by using “moves” instead of old-school “copies“. Having to wrap our args with std::move() to signal the compiler that we want a “move” instead of “copy” was well worth the effort, no?

Summarizing the gist of this post; please don’t forget to write your own simple “move” operations if you want to leverage the “free” STL container “move” performance gains in the copyable classes you write that contain STL containers. 🙂

NOTE1: I ran the code in this post on my Win 8.1 Lenovo A-730 all-in-one desktop using GCC 4.8/MinGW and MSVC++13. I also ran it on the Coliru online compiler (GCC 4.8). All test runs yielded similar results. W00t!

NOTE2: When I first wrote the “move” member functions for the UserType class, I forgot to wrap other.vints with the overhead-free std::move() function. Thus, I was scratching my (bald) head for a while because I didn’t know why I wasn’t getting any performance boost over the standard copy operations. D’oh!

NOTE3: If you want to copy and paste the code from here into your editor and explore this very moving topic for yourself, here is the non-.png listing:

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

#include <vector>

class UserType {

public:

// 100 million ints with value 100

UserType() : vints(100000000, 100) {

}

//move ctor

UserType(UserType&& other) {

//invoke std::vector move assignment

vints = std::move(other.vints);

}

//move assignment

UserType& operator=(UserType&& other) {

//invoke std::vector move assignment

vints = std::move(other.vints);

return *this;

}

UserType(const UserType& other) = default;

UserType& operator=(const UserType& other) = default;

private:

std::vector<int> vints;

};

int main() {

UserType ut1{};

UserType ut2{};

using namespace std;

using namespace std::chrono;

auto start = steady_clock::now();

ut2 = std::move(ut1);

UserType ut3{std::move(ut2)};

auto end = steady_clock::now();

cout << "Time for move ctor + move assignment (micros) = "

<< duration_cast<microseconds>((end-start)).count()

<< endl;

UserType ut4{};

UserType ut5{};

start = steady_clock::now();

ut5 = ut4;

UserType ut6{ut5};

end = steady_clock::now();

cout << "Time for copy ctor + copy assignment (micros) = "

<< duration_cast<microseconds>((end-start)).count()

<< endl;

return 0;

}

Auto Forgetfulness

The other day, I started tracking down a defect in my C++11 code that was exposed by a unit test. At first, I thought the bugger had to be related to the domain logic I was implementing. However, after 4 hours of inspection/testing/debugging, the answer simply popped into my head, seemingly out of nowhere (funny how that works, no?). It was due to my “forgetting” a subtle characteristic of the C++11 automatic type deduction feature implemented via the “auto” keyword.

To elaborate further, take a look at this simple function prototype:

SomeReallyLongTypeName& getHandle();

On first glance, you might think that the following call to getHandle() would return a reference to an internal, non-temporary, object of type SomeReallyLongTypeName that resides within the scope of the getHandle() function.

auto x = getHandle();

However, it doesn’t. After execution returns to the caller, x contains a copy of the internal, non-temporary object of type SomeReallyLongTypeName. If SomeReallyLongTypeName is non-copyable, then the compiler would have mercifully clued me into the problem with an error message (copy ctor is private (or deleted)).

To get what I really want, this code does the trick:

auto& x = getHandle();

The funny thing is that I already know “auto” ignores type qualifications from routinely writing code like this:

std::vector<int> vints{};

//fill up "vints" somehow

for(auto& elem : vints) {

//do something to each element of vints

}

However, since it was the first time I used “auto” in a new context, its type-qualifier-ignoring behavior somehow slipped my feeble mind. I hate when that happens.

Periodic Processing With Standard C++11 Facilities

With the addition of the <chrono> and <thread> libraries to the C++11 standard library, programs that require precise, time-synchronized functionality can now be written without having to include any external, non-standard libraries (ACE, Boost, Poco, pthread, etc) into the development environment. However, learning and using the new APIs correctly can be a non-trivial undertaking. But, there’s a reason for having these rich and powerful APIs:

The time facilities are intended to efficiently support uses deep in the system; they do not provide convenience facilities to help you maintain your social calendar. In fact, the time facilities originated with the stringent needs of high-energy physics. Furthermore, language facilities for dealing with short time spans (e.g., nanoseconds) must not themselves take significant time. Consequently, the <chrono> facilities are not simple, but many uses of those facilities can be very simple. – Bjarne Stroustrup (The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition).

Many soft and hard real-time applications require chunks of work to be done at precise, periodic intervals during run-time. The figure below models such a program. At the start of each fixed time interval T, “doStuff()” is invoked to perform an application-specific unit of work. Upon completion of the work, the program (or task/thread) “sleeps” under the care of the OS until the next interval start time occurs. If the chunk of work doesn’t complete before the next interval starts, or accurate, interval-to-interval periodicity is not maintained during operation, then the program is deemed to have “failed“. Whether the failure is catastrophic or merely a recoverable blip is application-specific.

Although the C++11 time facilities support time and duration manipulations down to the nanosecond level of precision, the actual accuracy of code that employs the API is a function of the precision and accuracy of the underlying hardware and OS platform. The C++11 API simply serves as a standard, portable bridge between the coder and the platform.

The figure below shows the effect of platform inaccuracy on programs that need to maintain a fixed, periodic timeline. Instead of “waking up” at perfectly constant intervals of T, some jitter is introduced by the platform. If the jitter is not compensated for, the program will cumulatively drift further and further away from “real-time” as it runs. Even if jitter compensation is applied on an interval by interval basis to prevent drift-creep, there will always be some time inaccuracy present in the application due to the hardware and OS limitations. Again, the specific application dictates whether the timing inaccuracy is catastrophic or merely a nuisance to be ignored.

The simple UML activity diagram below shows the cruxt of what must be done to measure the “wake-up error” on a given platform.

On each pass through the loop:

- The OS wakes us up (via <thread>)

- We retrieve the current time (via <chrono>)

- We compute the error between the current time and the desired time (via <chrono>)

- We compute the next desired wake-up time (via <chrono>)

- We tell the OS to put us to sleep until the desired wake-up time occurs (via <thread>)

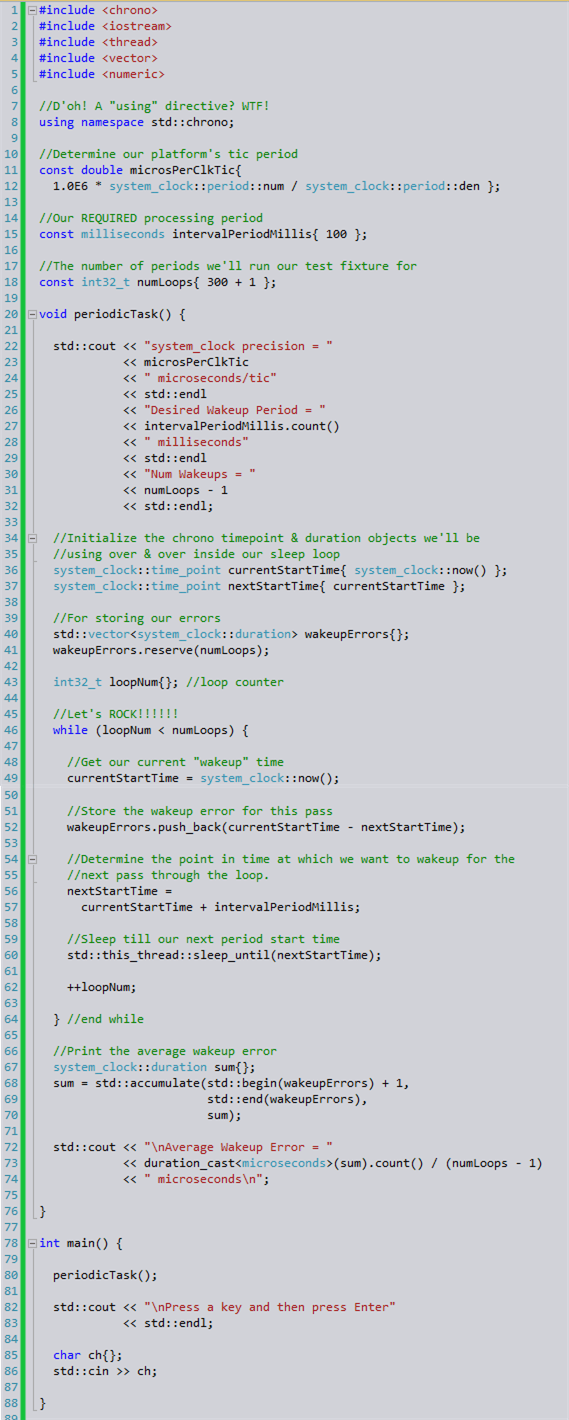

For your viewing and critiquing pleasure, the source code for a simple, portable C++11 program that measures average “wakeup error” is shown here:

The figure below shows the results from a typical program run on a Win7 (VC++13) and Linux (GCC 4.7.2) platform. Note that the clock precision on the two platforms are different. Also note that in the worst case, the 100 millisecond period I randomly chose for the run is maintained to within an average of .1 percent over the 30 second test run. Of course, your mileage may vary depending on your platform specifics and what other services/daemons are running on that platform.

The purpose of writing and running this test program was not to come up with some definitive, quantitative results. It was simply to learn and play around with the <chrono> and <thread> APIs; and to discover how qualitatively well the software and hardware stacks can accommodate software components that require doing chunks of work on fixed, periodic, time boundaries.

In case anyone wants to take the source code and run with it, I’ve attached it to the site as a pdf: periodicTask.pdf. You could simulate chunks of work being done within each interval by placing a std::this_thread::sleep_for() within the std::this_thread::sleep_until() loop. You could elevate numLoops and intervalPeriodMillis from compile time constants to command line arguments. You can use std::minmax_element() on the wakeup error samples.

C++1y Automatic Type Deduction

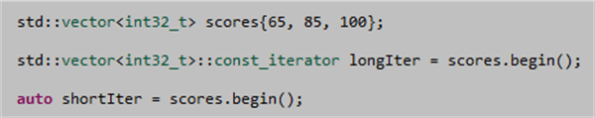

The addition, err, redefinition of the auto keyword in C++11 was a great move to reduce code verbosity during the definition of local variables:

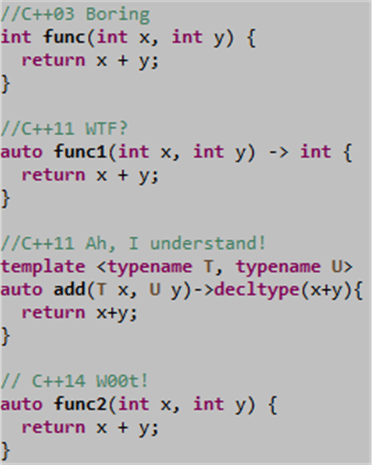

In addition to this convenient usage, employing auto in conjunction with the new (and initially weird) function-trailing-return-type syntax is useful for defining function templates that manipulate multiple parameterized types (see the third entry in the list of function definitions below).

In the upcoming C++14 standard, auto will also become useful for defining normal, run-of-the-mill, non-template functions. As the fourth entry below illustrates, we’ll be able to use auto in function definitions without having to use the funky function-trailing-return-type syntax (see the useless, but valid, second entry in the list).

For a more in depth treatment of C++11’s automatic type deduction capability, check out Herb Sutter’s masterful post on the new AAA (Almost Always Auto) idiom.