Archive

Easier To Use, And More Expressive

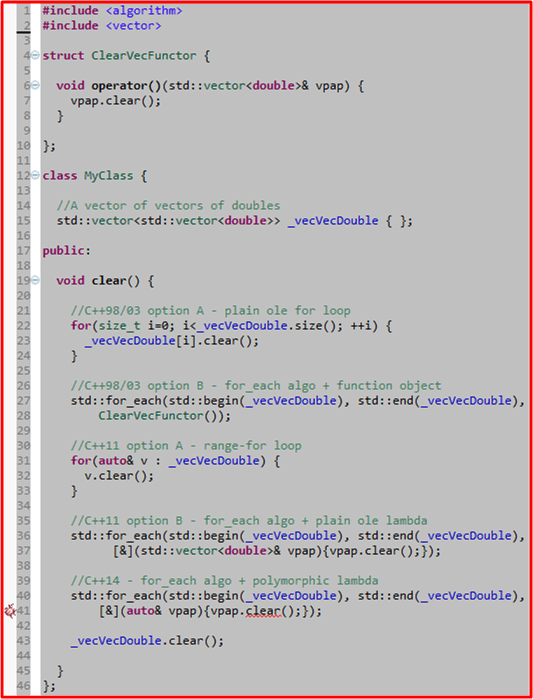

One of the goals for each evolutionary increment in C++ is to decrease the probability of an average programmer from making mistakes by supplanting “old style” features/idioms with new, easier to use, and more expressive alternatives. The following code sample attempts to show an example of this evolution from C++98/03 to C++11 to C++14.

In C++98/03, there were two ways of clearing out the set of inner vectors in the vector-of-vectors-of-doubles data structure encapsulated by MyClass. One could use a plain ole for-loop or the std::for_each() STL algorithm coupled with a remotely defined function object (ClearVecFunctor). I suspect that with the exception of clever language lawyers, blue collar programmers (like me) used the simple for-loop option because of its reduced verbosity and compactness of expression.

With the arrival of C++11 on the scene, two more options became available to programmers: the range-for loop, and the std::for_each() algorithm combined with an inline-defined lambda function. The range-for loop eliminated the chance of “off-by-one” errors and the lambda function eliminated the inconvenience of having to write a remotely located functor class.

The ratification of the C++14 standard brought yet another convenient option to the table: the polymorphic lambda. By using auto in the lambda argument list, the programmer is relieved of the obligation to explicitly write out the full type name of the argument.

This example is just one of many evolutionary improvements incorporated into the language. Hopefully, C++17 will introduce many more.

Note: The code compiles with no warnings under gcc 4.9.2. However, as you can see in the image from the bug placed on line 41, the Eclipse CDT indexer has not caught up yet with the C++14 specification. Because auto is used in place of the explicit type name in the lambda argument list, the indexer cannot resolve the std::vector::clear() member function.

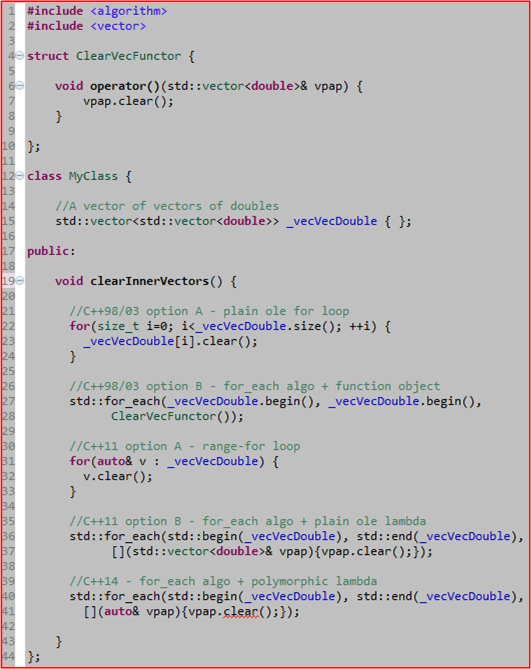

8/26/15 Update – As a result of reader code reviews provided in the comments section of this post, I’ve updated the code as follows:

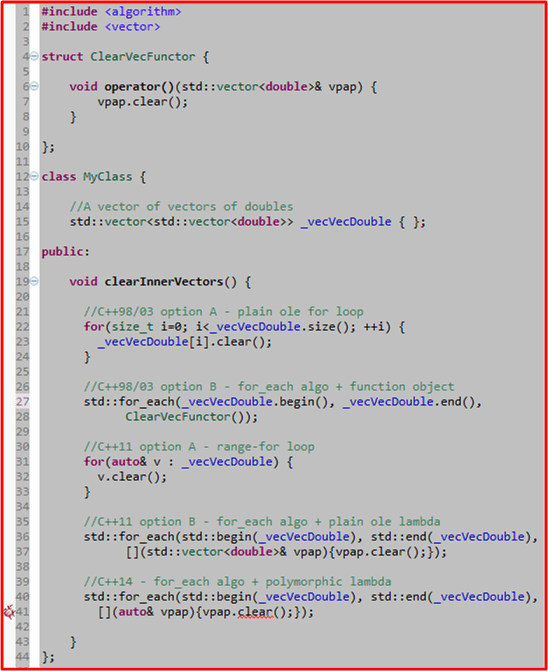

8/29/15 Update – A Fix to the Line 27 begin-begin bug:

Is It Safe?

Remember this classic torture scene in “Marathon Man“? D’oh!  Now, suppose you had to create the representation of a message that simply aggregates several numerical measures into one data structure:

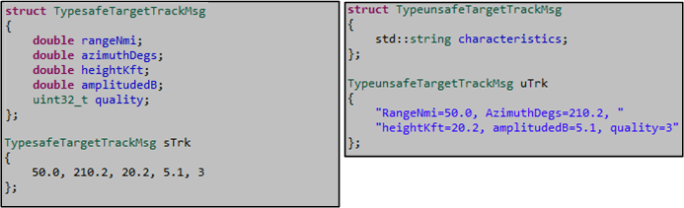

Now, suppose you had to create the representation of a message that simply aggregates several numerical measures into one data structure:

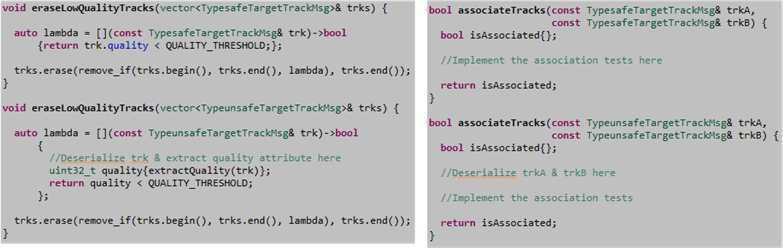

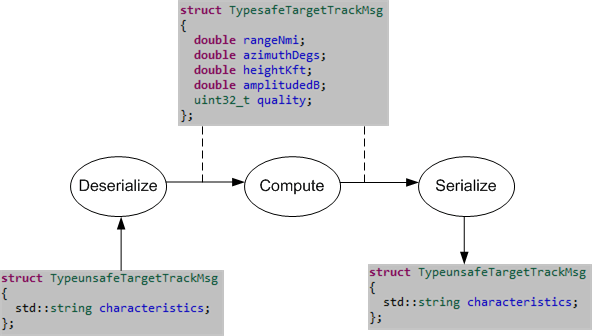

Given no information other than the fact that some numerical computations must be performed on each individual target track attribute within your code, which implementation would you choose for your internal processing? The binary, type-safe, candidate, or the text, type-unsafe, option? If you chose the type-unsafe option, then you’d impose a performance penalty on your code every time you needed to perform a computation on your tracks. You’d have to deserialize and extract the individual track attribute(s) before implementing the computations:

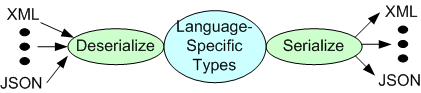

If your application is required to send/receive track messages over a “wire” between processing nodes, then you’d need to choose some sort of serialization/deserialization protocol along with an over-the-wire message format. Even if you were to choose a text format (JSON, XML) for the wire, be sure to deserialize the input as soon as possible and serialize on output as late as possible. Otherwise you’ll impose an unnecessary performance hit on your code every time you have to numerically manipulate the fields in your message.

More generally….

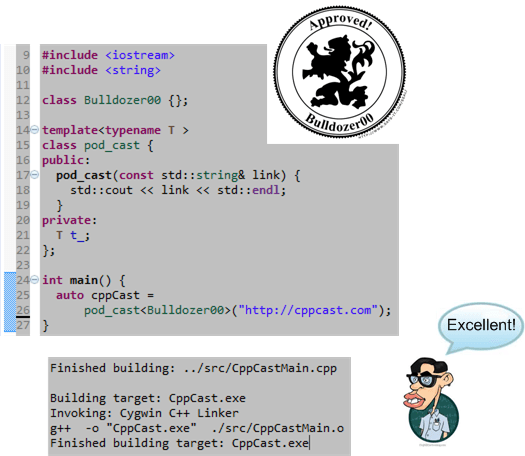

Template Argument 1 Is Invalid

I’d like to thank the hard working hosts of the first ever C++ podcast, Rob Irving and Jason Turner, for mentioning my “Time To Get Moving!” blog post on episode #16. If you’re a C++ coder and you’re not a subscriber to this great learning resource, then shame on you.

Hey Rob and Jason, you guys gotta slightly modify your logo. You’re statement doesn’t compile because it’s illegal to use the “+” character in an identifier name 🙂

Since I pointed out the bug, what do you guys think about changing your template argument,”C++“, to “Bulldozer00“?

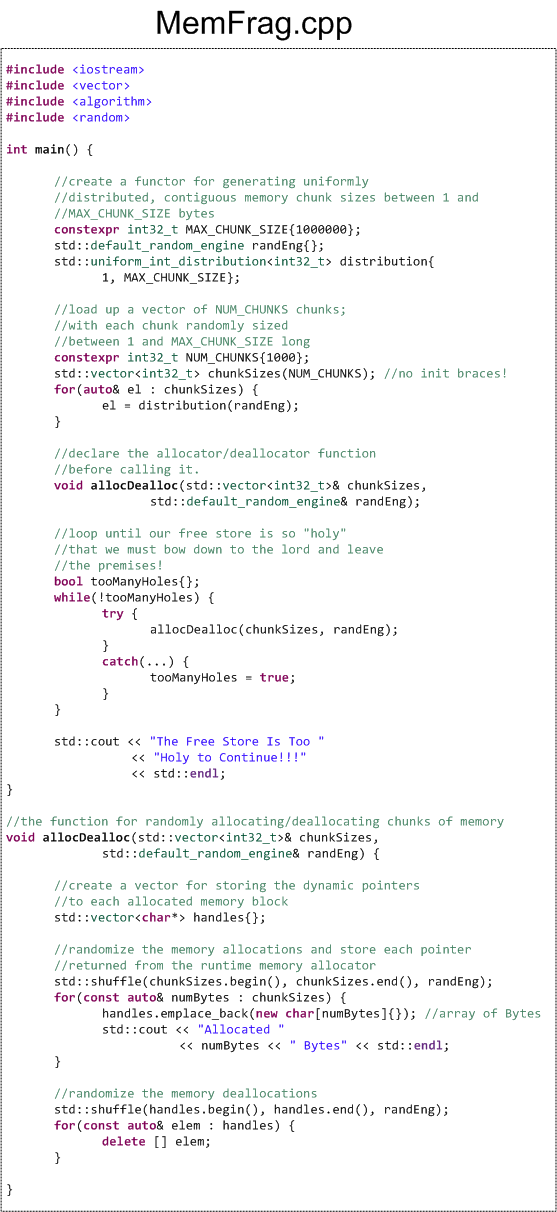

Holier Than Thou

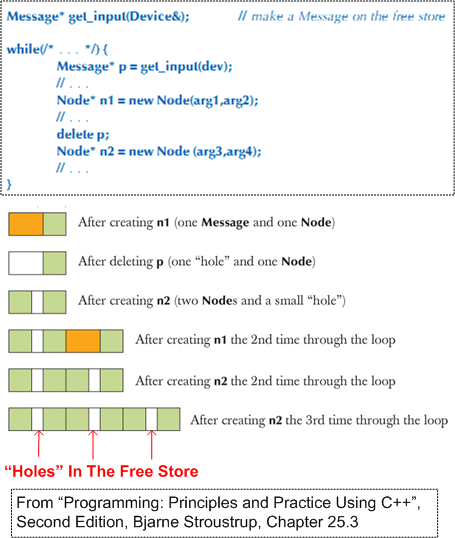

Since C++ (by deliberate design) does not include a native garbage collector or memory compactor, programs that perform dynamic memory allocation and de-allocation (via explicit or implicit use of the “new” and “delete” operators) cause small “holes” to accumulate in the free store over time. I guess you can say that C++ is “holier than thou“. 😦  Mind you, drilling holes in the free store is not the same as leaking memory. A memory leak is a programming bug that needs to be squashed. A fragmented free store is a “feature“. His holiness can become an issue only for loooong running C++ programs and/or programs that run on hardware with small RAM footprints. For those types of niche systems, the best, and perhaps only, practical options available for preventing any holes from accumulating in your briefs are to eliminate all deletes from the code:

Mind you, drilling holes in the free store is not the same as leaking memory. A memory leak is a programming bug that needs to be squashed. A fragmented free store is a “feature“. His holiness can become an issue only for loooong running C++ programs and/or programs that run on hardware with small RAM footprints. For those types of niche systems, the best, and perhaps only, practical options available for preventing any holes from accumulating in your briefs are to eliminate all deletes from the code:

- Perform all of your dynamic memory allocations at once, during program initialization (global data – D’oh!), and only utilize the CPU stack during runtime for object creation/destruction.

- If your application inherently requires post-initialization dynamic memory usage, then use pre-allocated, fixed size, unfragmentable, pools and stacks to acquire/release data buffers during runtime.

If your system maps into the “holes can freakin’ kill someone” category and you don’t bake those precautions into your software design, then the C++ runtime may toss a big, bad-ass, std::bad_alloc exception into your punch bowl and crash your party if it can’t find a contiguous memory block big enough for your impending new request. For large software systems, refactoring the design to mitigate the risk of a fragmented free store after it’s been coded/tested falls squarely into the expensive and ominous “stuff that’s hard to change” camp. And by saying “stuff that’s hard to change“, I mean that it may be expensive, time consuming, and technically risky to reweave your basket (case). In an attempt to verify that the accumulation of free store holes will indeed crash a program, I wrote this hole-drilling simulator:  Each time through the while loop, the code randomly allocates and deallocates 1000 chunks of memory. Each chunk is comprised of a random number of bytes between 1 and 1MB. Thus, the absolute maximum amount of memory that can be allocated/deallocated during each pass through the loop is 1 GB – half of the 2 GB RAM configured on the linux virtual box I am currently running the code on. The hole-drilling simulator has been running for days – at least 5 straight. I’m patiently waiting for it to exit – and hopefully when it does so, it does so gracefully. Do you know how I can change the code to speed up the time to exit?

Each time through the while loop, the code randomly allocates and deallocates 1000 chunks of memory. Each chunk is comprised of a random number of bytes between 1 and 1MB. Thus, the absolute maximum amount of memory that can be allocated/deallocated during each pass through the loop is 1 GB – half of the 2 GB RAM configured on the linux virtual box I am currently running the code on. The hole-drilling simulator has been running for days – at least 5 straight. I’m patiently waiting for it to exit – and hopefully when it does so, it does so gracefully. Do you know how I can change the code to speed up the time to exit?

Note1: This post doesn’t hold a candle to Bjarne Stroustrup’s thorough explanation of the “holiness” topic in chapter 25 of “Programming: Principles and Practice Using C++, Second Edition“. If you’re a C++ programmer (beginner, intermediate, or advanced) and you haven’t read that book cover-to-cover, then… you should.

Note2: For those of you who would like to run/improve the hole-drilling simulator, here is the non-.png source code listing:

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

int main() {

//create a functor for generating uniformly

//distributed, contiguous memory chunk sizes between 1 and

//MAX_CHUNK_SIZE bytes

constexpr int32_t MAX_CHUNK_SIZE{1000000};

std::default_random_engine randEng{};

std::uniform_int_distribution distribution{

1, MAX_CHUNK_SIZE};

//load up a vector of NUM_CHUNKS chunks;

//with each chunk randomly sized

//between 1 and MAX_CHUNK_SIZE long

constexpr int32_t NUM_CHUNKS{1000};

std::vector chunkSizes(NUM_CHUNKS); //no init braces!

for(auto& el : chunkSizes) {

el = distribution(randEng);

}

//declare the allocator/deallocator function

//before calling it.

void allocDealloc(std::vector& chunkSizes,

std::default_random_engine& randEng);

//loop until our free store is so "holy"

//that we must bow down to the lord and leave

//the premises!

bool tooManyHoles{};

while(!tooManyHoles) {

try {

allocDealloc(chunkSizes, randEng);

}

catch(const std::bad_alloc&) {

tooManyHoles = true;

}

}

std::cout << "The Free Store Is Too "

<< "Holy to Continue!!!"

<< std::endl;

}

//the function for randomly allocating/deallocating chunks of memory

void allocDealloc(std::vector& chunkSizes,

std::default_random_engine& randEng) {

//create a vector for storing the dynamic pointers

//to each allocated memory block

std::vector<char*> handles{};

//randomize the memory allocations and store each pointer

//returned from the runtime memory allocator

std::shuffle(chunkSizes.begin(), chunkSizes.end(), randEng);

for(const auto& numBytes : chunkSizes) {

handles.emplace_back(new char[numBytes]{}); //array of Bytes

std::cout << "Allocated "

<< numBytes << " Bytes" << std::endl;

}

//randomize the memory deallocations

std::shuffle(handles.begin(), handles.end(), randEng);

for(const auto& elem : handles) {

delete [] elem;

}

}

If you do copy/paste/change the code, please let me know what you did and what you discovered in the process.

Note3: I have an intense love/hate relationship with the C++ posts that I write. I love them because they attract the most traffic into this gawd-forsaken site and I always learn something new about the language when I compose them. I hate my C++ posts because they take for-freakin’-ever to write. The number of create/reflect/correct iterations I execute for a C++ post prior to queuing it up for publication always dwarfs the number of mental iterations I perform for a non-C++ post.

Acting In C++

Because they’re a perfect fit for mega-core processors and they’re safer and more enjoyable to program than raw, multi-threaded, systems, I’ve been a fan of Actor-based concurrent systems ever since I experimented with Erlang and Akka (via its Java API). Thus, as a C++ programmer, I was excited to discover the “C++ Actor Framework” (CAF). Like the Akka toolkit/runtime, the CAF is based on the design of the longest living, proven, production-ready, pragmatic, actor-based, language that I know of – the venerable Erlang programming language.

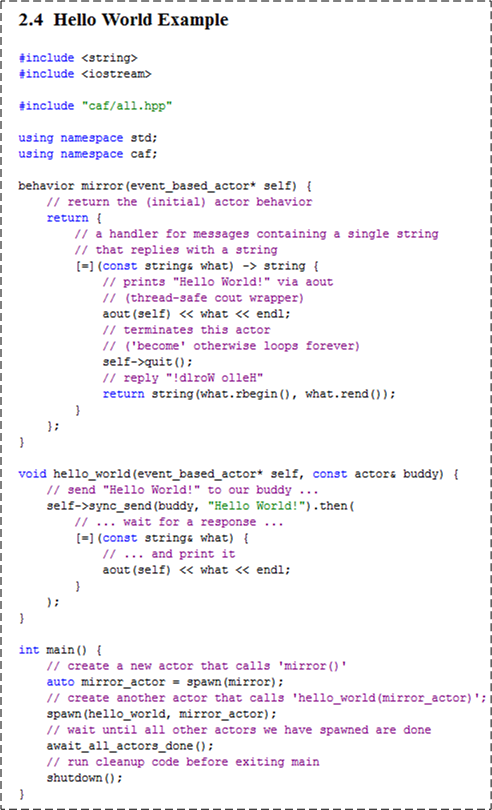

Curious to check out the CAF, I downloaded, compiled, and installed the framework source code with nary a problem (on CentOS 7.0, GCC 4.8.2). I then built and ran the sample “Hello World” program presented in the user manual:

As you can see, the CAF depends on the use one of my favorite C++11 features – lambda functions – to implement actor behavior.

The logic in main() uses the CAF spawn() function to create two concurrently running, message-exchanging (messages of type std::string), actors named “mirror” and “hello_world“. During the spawning of the “hello_world” actor, the main() logic passes it a handle (via const actor&) to the previously created “mirror” actor so that “hello_world” can asynchronously communicate with “mirror” via message-passing. Then, much like the parent thread in a multi-threaded program “join()“s the threads it creates to wait for the threads to complete their work, the main() thread of control uses the CAF await_all_actors_done() function to do the same for the two actors it spawns.

When I ran the program as a local C++ application in the Eclipse IDE, here is the output that appeared in the console window:

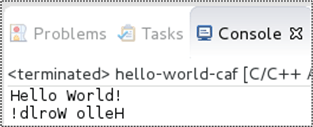

The figure below visually illustrates the exchange of messages between the program’s actors during runtime. Upon being created, the “hello_world” actor sends a text message (via sync_send()) containing “Hello World” as its payload to the previously spawned “mirror” actor. The “hello_world” actor then immediately chains the then() function to the call to synchronously await for the response message it expects back from the “mirror” actor. Note that a lambda function that will receive and print the response message string to the console (via the framework’s thread-safe aout object) is passed as an argument into the then() function.

Looking at the code for the “mirror” actor, we can deduce that when the framework spawns an instance of it, the framework gives the actor a handle to itself and the actor returns the behavior (again, in the form of a lambda function) that it wants the framework to invoke each time a message is sent to the actor. The “mirror” actor behavior: prints the received message to the console, tells the framework that it wants to terminate itself (via the call to quit()), and returns a mirrored translation of the input message to the framework for passage back to the sending actor (in this case, the “hello_world” actor).

Note that the application contains no explicit code for threads, tasks, mutexes, locks, atomics, condition variables, promises, futures, or thread-safe containers to futz with. The CAF framework hides all the underlying synchronization and message passing minutiae under the abstractions it provides so that the programmer can concentrate on the application domain functionality. Great stuff!

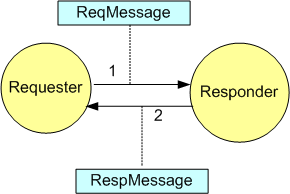

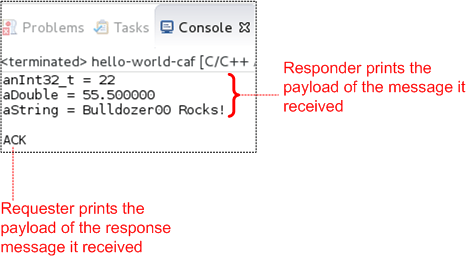

I modified the code slightly so that the application actors exchange user-defined message types instead of std::strings.

Here is the modified code:

struct ReqMessage {

int32_t anInt32_t;

double aDouble;

string aString;

};

struct RespMessage {

enum class AckNack{ACK, NACK};

AckNack response;

};

void printMsg(event_based_actor* self, const ReqMessage& msg) {

aout(self) << "anInt32_t = " << msg.anInt32_t << endl

<< "aDouble = " << msg.aDouble << endl

<< "aString = " << msg.aString << endl

<< endl;

}

void fillReqMessage(ReqMessage& msg) {

msg.aDouble = 55.5;

msg.anInt32_t = 22;

msg.aString = "Bulldozer00 Rocks!";

}

behavior responder(event_based_actor* self) {

// return the (initial) actor behavior

return {

// a handler for messages of type ReqMessage

// and replies with a RespMessage

[=](const ReqMessage& msg) -> RespMessage {

// prints the content of ReqMessage via aout

// (thread-safe cout wrapper)

printMsg(self, msg);

// terminates this actor *after* the return statement

// ('become' a quitter, otherwise loops forever)

self->quit();

// reply with an "ACK"

return RespMessage{RespMessage::AckNack::ACK};

}};

}

void requester(event_based_actor* self, const actor& responder) {

// create & send a ReqMessage to our buddy ...

ReqMessage req{};

fillReqMessage(req);

self->sync_send(responder, req).then(

// ... wait for a response ...

[=](const RespMessage& resp) {

// ... and print it

RespMessage::AckNack payload{resp.response};

string txt =

(payload == RespMessage::AckNack::ACK) ? "ACK" : "NACK";

aout(self) << txt << endl;

});

}

int main() {

// create a new actor that calls 'responder()'

auto responder_actor = spawn(responder);

// create another actor that calls 'requester(responder_actor)';

spawn(requester, responder_actor);

// wait until all other actors we have spawned are done

await_all_actors_done();

// run cleanup code before exiting main

shutdown();

}

Scaling Up And Out

Ever since I discovered the venerable Erlang programming language and the great cast of characters (especially Joe Armstrong) behind its creation, I’ve been chomping at the bit to use it on a real, rent-paying, project. That hasn’t happened, but the next best thing has. I’m currently in the beginning stage of a project that will be using “Akka” to implement a web-based radar system gateway.

Akka is an Erlang-inspired toolkit and runtime system for the JVM that elegantly supports the design and development of highly concurrent and distributed applications. It’s written in Scala, but it has both Scala and Java language bindings.

Jonas Boner, the creator of Akka, was blown away by the beauty of Erlang and its ability to support “nine nines” of availability – as realized in a commercial Ericsson telecom product. At first, he tried to get clients and customers to start using Erlang. But because Erlang has alien, Prologue-based syntax, and its own special VM/development infrastructure, it was a tough sell. Thus, he became determined to bring”Erlangness” to the JVM to lower the barriers to entry. Jonas seems to be succeeding in his crusade.

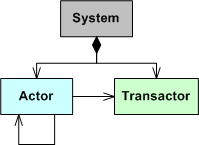

At the simplest level of description, an Akka-based application is comprised of actors running under the control of an overarching Akka runtime system container. An actor is an autonomous, reactive entity that contains state, behavior, and an input mailbox from which it consumes asynchronously arriving messages. An actor communicates with its parents/siblings by issuing immutable, fire-and-forget (or asynchronous request-and-remember), messages to them. The only way to get inside the “head” of an actor is to send messages to it. There are no backdoors that allow other actors to muck with the inner state of an actor during runtime. Like people, actors can be influenced, but not explicitly coerced or corrupted, by others. However, also like people, actors can be terminated for errant behavior by their supervisors. 🙂

For applications that absolutely require some sort of shared state between actors, Akka provides transactors (and agents). A transactor is an implementation of software transactional memory that serializes access to shared memory without the programmer having to deal with tedious, error-prone, mutexes and locks. In essence, the Akka runtime unshackles programmers from manually handling the frustrating minutiae (deadlocks, race conditions (Heisenbugs), memory corruption, scalability bottlenecks, resource contention) associated with concurrent programming. Akka allows programmers to work at a much more pleasant, higher level of abstraction than the traditional, bare bones, threads/locks model. You spend more time solving domain-level problems than battling with the language/library implementation constraints.

You design an Akka based system by, dare I say, exercising some upfront design brain muscle:

- decomposing and allocating application functionality to actors,

- allocating data to inter-actor messages and transactors,

- wiring the actors together to structure your concurrent system as a network of cooperating automatons.

The Akka runtime supervises the application by operating unobtrusively in the background:

- mapping actors to OS threads and hardware cores,

- activating an actor for each message that appears in its mailbox,

- handling actor failures,

- realizing the message passing mechanisms.

Gee, I wonder if the agile TDD and the “no upfront anything” practices mix well with concurrent, distributed system design. Silly me. Of course they do. Like all things agile, they’re universally applicable in all contexts. (Damn, I thought I’d make it through this whole post without dissing the dogmatic agile priesthood, but I failed yet again.)

Akka not only makes it easy to scale up on a multi-core processor, Akka makes it simple to scale out and distribute (if needed) your concurrent design amongst multiple computing nodes via a URL-based addressing scheme.

There is much more deliciousness to Akka than I can gush about in this post (most notably, actor supervision trees, futures, routers, message dispatchers, etc), but you can dive deeper into Akka (or Erlang) if I’ve raised the hairs on the back of your geeky little neck. The online Akka API documentation is superb. I also have access to the following three Akka books via my safaribooksonline account:

Since C++ is my favorite programming language, I pray that the ISO C++ committee adds Erlang-Akka like abstractions and libraries to the standard soon. I know that proposals for software transactional memory and improved support for asynchronous tasking and futures are being worked on as we speak, but I don’t know if they’ll be polished enough to add to the 2017 standard. Hurry up guys :).

Regime Change

Revolution is glamorous and jolting; evolution is mundane and plodding. Nevertheless, evolution is sticky and long-lived whereas revolution is slippery and fleeting.

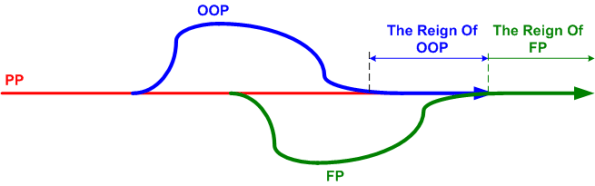

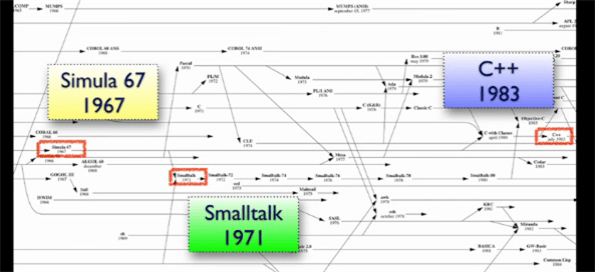

As the figure below from Neal Ford’s OSCON “Functional Thinking” talk reveals, it took a glacial 16 years for Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) to firmly supplant Procedural Programming (PP) as the mainstream programming style of choice. There was no revolution.

Starting with, arguably, the first OOP language, Simula, the subsequent appearance of Smalltalk nudged the acceptance of OOP forward. The inclusion of object-oriented features in C++ further accelerated the adoption of OOP. Finally, the emergence of Java in the late 90’s firmly dislodged PP from the throne in an evolutionary change of regime.

I suspect that the main reason behind the dethroning of PP was the ability of OOP to more gracefully accommodate the increasing complexity of software systems through the partitioning and encapsulation of state.

Mr. Ford asserts, and I tend to agree with him, that functional programming is on track to inherit the throne and relegate OOP to the bench – right next to PP. The main force responsible for the ascent of FP is the proliferation of multicore processors. PP scatters state, OOP encapsulates state, and FP eschews state. Thus, the FP approach maps more naturally onto independently running cores – minimizing the need for performance-killing synchronization points where one or more cores wait for a peer core to finish accessing shared memory.

The mainstream-ization of FP can easily be seen by the inclusion of functional features into C++ (lambdas, tasks, futures) and the former bastion of pure OOP, Java (parallel streams). Rather than cede the throne to pure functional languages like the venerable Erlang, these older heavyweights are joining the community of the future. Bow to the king, long live the king.

On The Origin Of Features

Thanks to an angel on the blog staff at the ISO C++ web site, my last C++ post garnered quite a few hits that were sourced from that site. Thus, I’m following it up with another post based on the content of Bjarne Stroustrup’s brilliant and intimate book, “The Design And Evolution Of C++“.

The drawing below was generated from a larger, historical languages chart provided by Bjarne in D&E. It reminds me of a couple of insightful quotes:

“Complex systems will evolve from simple systems much more rapidly if there are stable intermediate forms than if there are not.” — Simon, H. 1982. The Sciences of the Artificial.

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked… A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system.” — Gall, J. 1986. Systemantics: How Systems Really Work and How They Fail.

A we can see from the figure, “Simula67” and “C” were the ultimate ancestral parents of the C++ programming language. Actually, as detailed in my last post, “frustration” and “unwavering conviction” were the true parents of creation, but they’re not languages so they don’t show up on the chart. 🙂

To complement the language-lineage figure, I compiled this table of early C++ features and their origins from D&E:

Finally, if you were wondering what Mr. Stroustrup’s personal feature-filtering criteria were (and still are 30+ years later!), here is the list:

If you consider yourself a dedicated C++ programmer who has never read D&E and my latest 2 posts haven’t convinced you to buy the book, then, well, you might not be a dedicated C++ programmer.

And In The Beginning…

I’m on my second pass through Bjarne Stroustrup’s “The Design And Evolution Of C++“. In the book, which was published exactly 20 years ago in 1994, Bjarne discloses all of the “whys” and “hows” that drove the growth of C++ up to the time of the book’s publication.

In the beginning, before there was C++ there was the even-more-nerdly-named “C With Classes” (CWC). Bjarne’s motivation for creating CWC was, as many inventions are, rooted in frustration:

This was exactly the kind of problem that I had become determined never again to attack without the proper tools. – Bjarne Stroustrup

The problem Bjarne refers to in the above quote was: “the task of exploring if/how the UNIX kernel could be distributed over a network of LAN-connected computers“. The preceding “never again” problem was for achieving his Ph.D. thesis at Cambridge University: “to study alternatives for the organization of system software for distributed systems“. Notice how the word “distributed” appears in both problems – and this was way back in the 70’s when bell bottoms were in fashion and prior to the rise of multi-core processor technology.

Even though he didn’t say why he chose the tool for his Cambridge Ph.D. thesis project, Bjarne used Nygaard and Dahl’s Simula programming language to code up a program for “simulating software running on a distributed system“. If you already know the history of C++, you won’t be surprised at Bjarne’s feelings for Simula or why he imported some of its key features into CWC:

It was a pleasure to write that simulator. The features of Simula were almost ideal for the purpose, and I was particularly impressed by the way the concepts of the language helped me think about the problems in my application. The class concept allowed me to map my application concepts into the language constructs in a direct way that made my code more readable than I had seen in any other language. The way Simula classes can act as co-routines made the inherent concurrency of my application easy to express.

Class hierarchies were used to express variants of application-level concepts. The use of class hierarchies was not heavy, though; the use of classes to express concurrency was much more important in the organization of my simulator.

During writing and initial debugging, I acquired a great respect for the expressiveness of Simula’s type system and its compiler’s ability to catch type errors.

In the above book quotes, we see the “whys” for:

- The appearance of the “Classes” word in “C With Classes“.

- CWC’s’s support for an object oriented programming style

- CWC’s static type system.

In contrast to Simula’s elegant expressiveness, its compile time and runtime performance were abysmal (garbage collection + runtime type checking + built-in concurrency = slooow). The runtime performance was so poor that Bjarne had to rewrite his simulator in low-level BPCL at the last second in order to get any meaningful results out of the program to stuff into his Ph.D. thesis.

Although there were several other pragmatic reasons for the appearance of the “C” in “C With Classes” (flexibility, ubiquity of available compilers, direct mapping of data to the hardware, simple linkage and runtime systems), performance ultimately drove the decision to use the well known and proven C language as ground zero for CWC – despite its funky syntactic quirks and unsafe features.

Curiously, support for concurrency was provided in CWC’s very first library in 1980. Concurrency appeared in the form of a tasking library and built-in support for two special functions recognized by the preprocessor: call() and return(). If defined by the programmer for a class, these functions would get implicitly invoked prior to entry and prior to exit of every class member function except for the constructor/destructor. They were required by the monitor class in the tasking library to acquire and release a lock for precluding data races. Interestingly, the call() and return() functions were later removed because “nobody used them but me“. We’d have to wait until 2011 for concurrency to return to C++ in the form of new libraries.

On exiting this post, I’d like to show you this e-mail exchange with Bjarne regarding the possibility of a book sequel in the near future:

Why not join an e-mail campaign to get Bjarne started on D&E II? So, go ahead. E-mail Bjarne like I did and plead with him to start penning the sequel. The 20 year trek from 1994 to 2014 has got to be filled with as many great “hows” and “whys” as D&E I.

A Grand Introduction

We should not be ashamed of bits. We should be proud of them. – Alex Stepanov

You may not interpret it in the same way as I did, but I found this cppcon conference introduction of Bjarne Stroustrup by programming scholar Alex Stepanov very moving:

Are you ashamed of bits, addresses, and being faithful to the machine? I’m not.