Archive

Underbid And Overpromise

As usual, I don’t get it. I don’t get the underbid-overpromise epidemic that’s been left untreated for ages. Proposal teams, under persistent pressure from executives to win contracts from customers, and isolated from hearing negative feedback by unintegrated program execution and product development teams, perpetually underbid on price/delivery and over-promise on product features and performance. This unquestioned underbid-overpromise industry worst practice has been entrenched in mediocracies since the dawn of the cover-your-ass, ironclad contract. The undiscussable but real tendency to, uh, “exaggerate” an org’s potential to deliver is baked into the system. That’s because competitors and customers are willing co-conspirators in this cycle of woe. The stalemate ensures that there’s no incentive for changing the busted system. As the saying goes; “if we can’t fix it, it ain’t broke!“. D’oh!

If a company actually could take the high road and submit more realistic proposals to customers, they’d go out of business because non-individual customers (i.e. dysfunctional org bureaucracies where no one takes responsibility for outcomes) choose the lowest bidder 99.99999% of the time. I said “actually could” in the previous sentence because most companies “can’t“. That’s because most are so poorly managed that they don’t know what or where their real costs are. Unrecorded overtime, vague and generic work breakdown structures, inscrutable processes, and wrongly charged time all guarantee that the corpo head sheds don’t have a clue where their major cost sinks are. Bummer.

Structure And The “ilities”

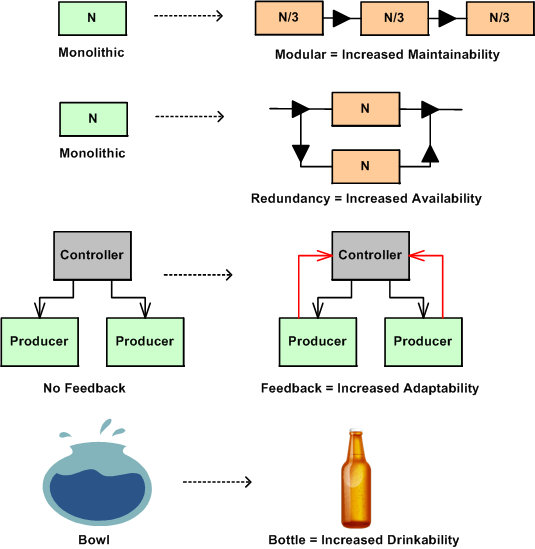

In nature, structure is an enabler or disabler of functional behavior. No hands – no grasping, no legs – no walking, no lungs – no living. Adding new functional components to a system enables new behavior and subtracting components disables behavior. Changing the arrangement of an existing system’s components and how they interconnect can also trade-off qualities of behavior, affectionately called the “ilities“. Thus, changes in structure effect changes in behavior.

The figure below shows a few examples of a change to an “ility” due to a change in structure. Given the structure on the left, the refactored structure on the right leads to an increase in the “ility” listed under the new structure. However, in moving from left to right, a trade-off has been made for the gain in the desired “ility”. For the monolithic->modular case, a decrease in end-to-end response-ability due to added box-to-box delay has been traded off. For the monolithic->redundant case, a decrease in buyability due to the added purchase cost of the duplicate component has been introduced. For the no feedback->feedback case, an increase in complexity has been effected due to the added interfaces. For the bowl->bottle example, a decrease in fill-ability has occurred because of the decreased diameter of the fill interface port.

The plea of this story is: “to increase your aware-ability of the law of unintended consequences”. What you don’t know CAN hurt you. When you are bound and determined to institute what you think is a “can’t lose” change to a system that you own and/or control, make an effort to discover and uncover the ilities that will be sacrificed for those that you are attempting to instill in the system. This is especially true for socio-technical systems (do you know of any system that isn’t a socio-technical system?) where the influence on system behavior by the technical components is always dwarfed by the influence of the components that are comprised of groups of diverse individuals.

Distributed Vs. Centralized Control

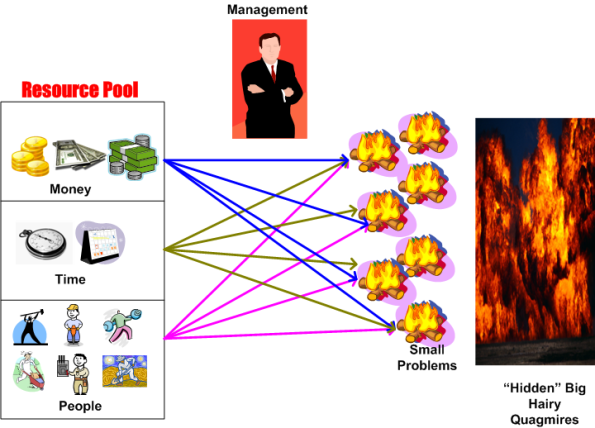

The figure below models two different configurations of a globally controlled, purposeful system of components. In the top half of the figure, the system controller keeps the producers aligned with the goal of producing high quality value stream outputs by periodically sampling status and issuing individualized, producer-specific, commands. This type of system configuration may work fine as long as:

- the producer status reports are truthful

- the controller understands what the status reports mean so that effective command guidance can be issued when problems manifest.

If the producer status reports aren’t truthful (politics, culture of fear, etc.), then the command guidance issued by the controller will not be effective. If the controller is clueless, then it doesn’t matter if the status reports are truthful. The system will become “hosed”, because the inevitable production problems that arise over time won’t get solved. As you might guess, when the status reports aren’t truthful and the controller is clueless, all is lost. Bummer.

The system configuration in the bottom half of the figure is designed to implement the “trust but verify” policy. In this design, the global controller directly receives samples of the value streams in addition to the producer status reports. The integration of value stream samples to the information cache available to the controller takes care of the “untruthful status report” risk. Again, if the controller is clueless, the system will get hosed. In fact, there is no system configuration that will work when the controller is incompetent.

How many system controllers do you know that actually sample and evaluate value stream outputs? For those that don’t, why do you think they don’t?

The system design below says “syonara dude” to the global omnipotent and omniscient controller. Each producer cell has its own local, closely coupled, and knowledgeable controller. Each local controller has a much smaller scope and workload than the previous two monolithic global controller designs. In addition, a single clueless local controller may be compensated for if the collective controller group has put into place a well defined, fair, and transparent set of criteria for replacement.

What types of systems does your organization have in place? Centrally controlled types, distributed control types, a mixture of both, hybrids? Which ones work well? How do you see yourself in your org? Are you a producer, a local controller, both a local controller and a producer, an overconfident global controller, a narcissistic controller of global controllers, a supreme controller of controllers who control other controllers who control yet other controllers? Do you sample and evaluate the value stream?

Mista Level

“Design is an intimate act of communication between the designer and the designed” – W. L. Livingston

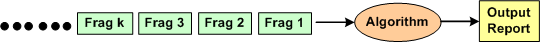

I’m currently in the process of developing an algorithm that is required to accumulate and correlate a set of incoming, fragmented messages in real-time for the purpose of producing an integrated and unified output message for downstream users.

The figure below shows a context diagram centered around the algorithm under development. The input is an unending, 24×7, high speed, fragmented stream of messages that can exhibit a fair amount of variety in behavior, including lost and/or corrupted and/or misordered fragments. In addition, fragmented message streams from multiple “sources” can be interlaced with each other in a non-deterministic manner. The algorithm needs to: separate the input streams by source, maintain/update an internal real-time database that tracks all sources, and periodically transmit source-specific output reports when certain validation conditions are satisfied.

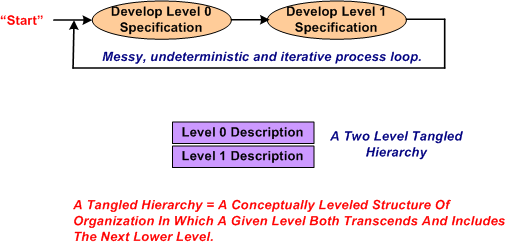

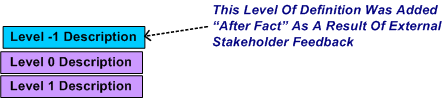

After studying literally 1000s of pages of technical information that describe the problem context that constrains the algorithm, I started sketching out and “playing” with candidate algorithm solutions at an arbitrary and subjective level of abstraction. Call this level of abstraction level 0. After looping around and around in the L0 thought space, I “subjectively decided” that I needed a second, more detailed but less abstract, level of definition, L1.

After maniacally spinning around within and between the two necessarily entangled hierarchical levels of definition, I arrived at a point of subjectively perceived stability in the design.

After receiving feedback from a fellow project stakeholder who needed an even more abstract level of description to communicate with other, non-development stakeholders, I decided that I mista level. However, I was able to quickly conjure up an L-1 description from the pre-existing lower level L0 and L1 descriptions.

Could I have started the algorithm development at L-1 and iteratively drilled downward? Could I have started at L1 and iteratively “syntegrated” upward? Would a one level-only (L-1, L0, or L1) specification be sufficient for all downstream stakeholders to use? The answers to all these questions, and others like them are highly subjective. I chose the jagged and discontinuous path that I traversed based on real-time situational assessment in the now, not based on some one-size-fits-all, step-by-step corpo approved procedure.

Three Things

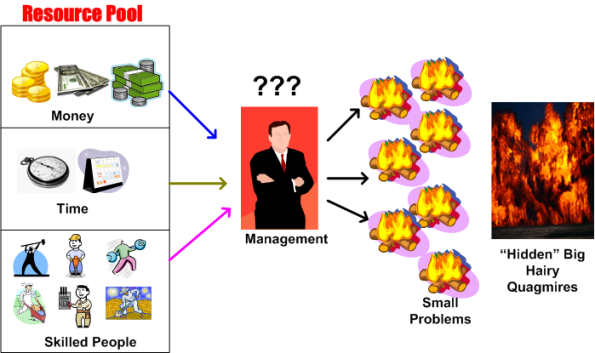

Three things: people, money, and time. These three interdependent resource types are the weapons that managers can deploy to create and sustain wealth for an organization. Managers are tasked with the challenge of judiciously apportioning these raw resources to the creation and sustainment of value-added products and services that solve customer problems. In addition to the creation and sustainment of products and services, the difficulty of continuously aligning and steering large groups of people toward the goals of growth and increasing profitability causes problem “fires” to be ignited within the corpo citadel. Bloated processes and warring factions are just two examples of the infinite variety of “pop up” fires that impede growth and profitability.

Left unchecked, internal brush fires always grow and merge into paradoxically massive, but hidden, forest fires that consume valuable resources. Brush fires feed on neglect and ignorance. Instead of creating wealth and continuously satisfying the external customer base, the three resource pools get exhausted by constantly being allocated to extinguishing internal fires.

Unless managers can “see” the growing fires, one or more massive fireballs can burn the organization to the ground. So, how can managers prevent massive fireballs from consuming would-be profits and customer goodwill? By constantly listening to, and investigating, and smartly acting on, the concerns of their people and their customers. Just listening is not enough. Just investigating is not enough. Just listening and investigating is not enough. Just listening and investigating and ineffective action is not enough. Listening, investigating, and effective action are all required.

No Good Deed

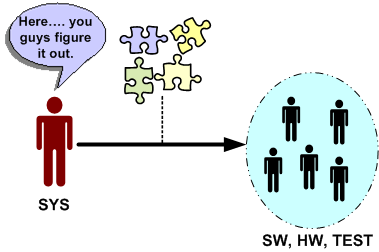

Let’s say that the system engineering culture at your hierarchically structured corpo org is such that virtually all work products handed off (down?) to hardware, software and test engineers are incomplete, inconsistent, fragmented, and filled with incomprehensible ambiguity. Another word that describes this type of low quality work is “camouflage”. Since it is baked into the “culture”, camouflage is expected, it’s taken for granted, and it’s burned into everyone’s mind that “that’s the way it is and that’s the way it always will be”.

Now, assume that someone comes along and breaks from the herd. He/she produces coherent, understandable, and directly usable outputs for the SW and HW and TEST engineers to make rapid downstream progress. How do you think the maverick system engineer would be treated by his/her peers? If you guessed: “with open arms”, then you are wrong. Statements like “that’s too much detail”, “it took too much time”, “you’re not supposed to do that”, “that’s not what our process says we should do”, etc, will reign down on the maverick. No good deed goes unpunished. Sic.

Why would this seemingly irrational and dysfunctional behavior occur? Because hirearchical corpo cultures don’t accept “change” without a fight, regardless of whether the change is good or bad. By embracing change, the changees have to first acknowledge the fact that what they were doing before the change wasn’t working. For engineers, or non-engineers with an engineering mindset of infallibility, this level of self-awareness doesn’t exist. If a maverick can’t handle the psychological peer pressure to return to the norm and produce shoddy work products, then the status quo will remain entrenched. Sadly but surely, this is what everyone wants, including management, and even more outrageously, the HW, SW, and TEST engineers. Bummer.

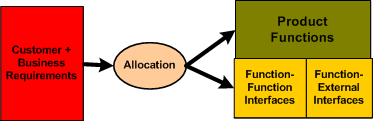

Functional Allocation VIII

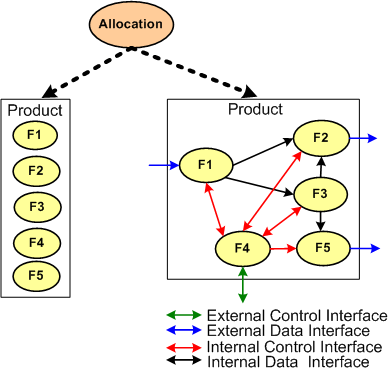

Typically, the first type of allocation work performed on a large and complex product is the shall-to-function (STF) allocation task. The figure below shows the inputs and outputs of the STF allocation process. Note that it is not enough to simply identify, enumerate, and define the product functions in isolation. An integral sub-activity of the process is to conjure up and define the internal and external functional interfaces. Since the dynamic interactions between the entities in an operational system (human or inanimate) give the system its power, I assert that interface definition is the most important part of any allocation process.

The figure below illustrates two alternate STF allocation outputs produced by different people. On the left, a bland list of unconnected product functions have been identified, but the functional structure has not been defined. On the right, the abstract functional product structure, defined by which functions are required to interact with other functions, is explicitly defined.

If the detailed design of each product function will require specialized domain expertise, then releasing a raw function list on the left to the downstream process can result in all kinds of counter productive behavior between the specialists whose functions need to communicate with each other in order to contribute to the product’s operation. Each function “owner” will each try to dictate the interface details to the “others” based on the local optimization of his/her own functional piece(s) of the product. Disrespect between team members and/or groups may ensue and bad blood may be spilled. In addition, even when the time consuming and contentious interface decision process is completed, the finished product will most likely suffer from a lack of holistic “conceptual integrity” because of the multitude of disparate interface specifications.

It is the lead system engineer’s or architect’s duty to define the function list and the interfaces that bind them together at the right level of detail that will preserve the conceptual integrity of the product. The danger is that if the system design owner goes too far, then the interfaces may end up being over-constrained and stifling to the function designers. Given a choice between leaving the interface design up to the team or doing it yourself, which approach would you choose?

Functional Allocation VII

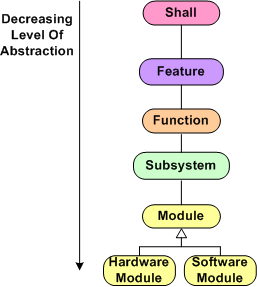

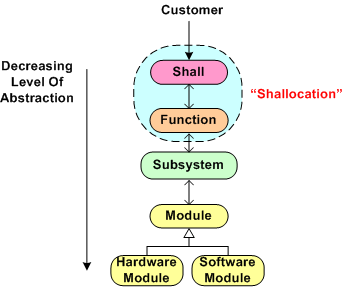

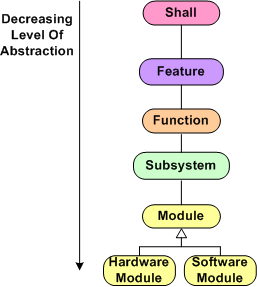

Here we are at blarticle number 7 on the unglamorous and boring topic of “Functional Allocation”. Once again, for a reference point of discussion, I present the hypothetical allocation tree below (your company does have a guidepost like this, doesn’t it?). In summary, product “shalls” are allocated to features, which are allocated to functions, which are allocated to subsystems, which are allocated to software and hardware modules. Depending on the size and complexity of the product to be built, one or more levels of abstraction can be skipped because the value added may not be worth the effort expended. For a simple software-only system that will run on Commercial-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) hardware, the only “allocation” work required to be performed is a shall-to-software module mapping.

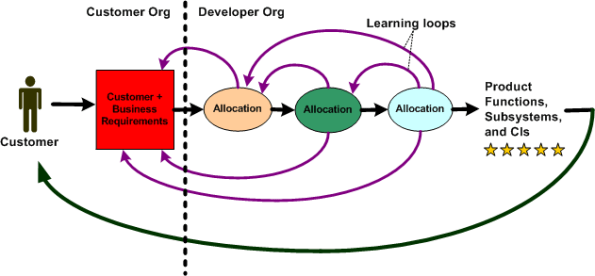

During the performance of any intellectually challenging human endeavor, mistakes will be made and learning will take place in real-time as the task is performed. That’s how fallible humans work, period. Thus for the output of such a task like “allocation” to be of high quality, an iterative and low latency feedback loop approach should be executed. When one qualified person is involved, and there is only one “allocation” phase to be performed (e.g. shall-to-module), there isn’t a problem. All the mistake-making, learning, and looping activity takes place within a single mind at the speed of thought. For (hopefully) long periods of time, there are no distractions or external roadblocks to interrupt the performance of the task.

For a big and complex multi-technology product where multiple levels of “allocation” need to be performed and multiple people and/or specialized groups need to be involved, all kinds of socio-technical obstacles and roadblocks to downstream success will naturally emerge. The figure below shows an effective product development process where iteration and loop-based learning is unobstructed. Communication flows freely between the development groups and organizations to correct mistakes and converge on an effective solution . Everything turns out hunky dory and the customer gets a 5 star product that he/she/they want and the product meets all expectations.

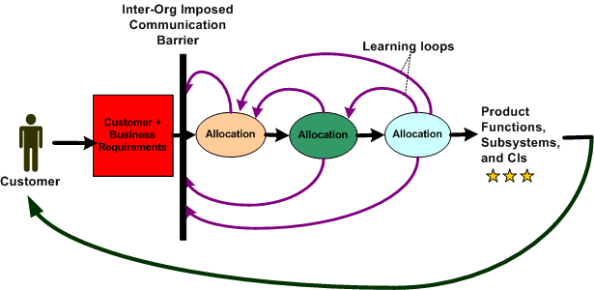

The figure below shows a dysfunctional product development process. For one reason or another, communication feedback from the developer org’s “allocation” groups is cut off from the customer organization. Since questions of understanding don’t get answered and mistakes/errors/ambiguities in the customer requirements go uncorrected, the end product delivered back to the customer underperforms and nobody ends up very happy. Bummer.

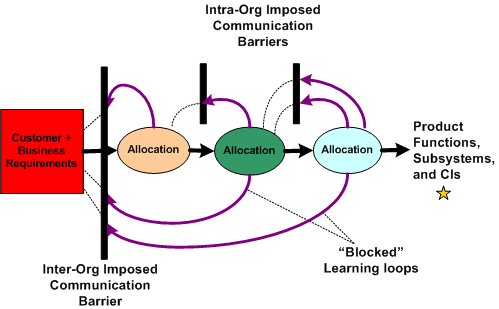

The figure below illustrates the worst possible case for everybody involved – a real mess. Not only do the customer and developer orgs not communicate; the “allocation” groups within the developer org don’t, or are prohibited from, communicating effectively with each other. The product that emerges from such a sequential linear-think process is a real stinker, oink oink. The money’s gone. the time’s gone, and the damn thang may not even work, let alone perform marginally.

Obviously, this situation is a massive failure of corpo leadership and sadly, I assert that it is the norm across the land. It is the norm because almost all big customer and developer orgs are structured as hierarchies of rank and stature with “standard” processes in place that require all kinds and numbers of unqualified people to “be in the loop” and approve (disapprove?) of every little step forward – lest their egos be hurt. Can a systemic, pervasive, baked-in problem like this be solved? If so, who, if anybody, has the ability to solve it? Can a single person overcome the massive forces of nature that keep a hierarchical ecosystem like this viable?

“The Biggest problem To Communication Is The Illusion That It Has Taken Place.” – George Bernard Shaw

Functional Allocation VI

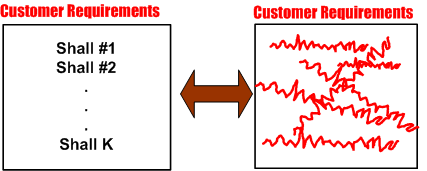

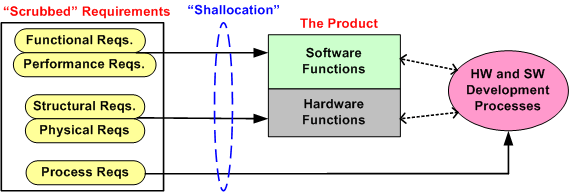

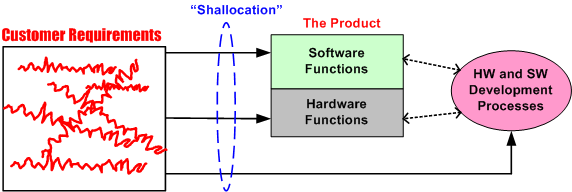

Every big system, multi-level, “allocation” process (like the one shown below) assumes that the process is initialized and kicked-off with a complete, consistent, and unambiguous set of customer-supplied “shalls”. These “shalls” need to be “shallocated” by a person or persons to an associated aggregate set of future product functions and/or features that will solve, or at least ameliorate, the customer’s problem. In my experience, a documented set of “shalls” is always provided with a contract, but the organization, consistency, completeness, and understandability of these customer level requirements often leaves much to be desired.

The figure below represents a hypothetical requirements mess. The mess might have been caused by “specification by committee”, where a bunch of people just haphazardly tossed “shalls” into the bucket according to different personal agendas and disparate perceptions of the problem to be solved.

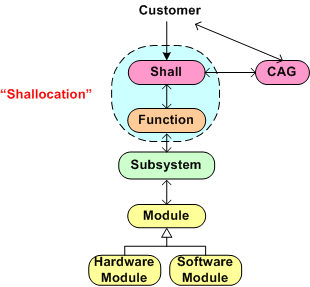

Given a fragmented and incoherent “mess”, what should be done next? Should one proceed directly to the Shall-To-Function (STF) process step? One alternative strategy, the performance of an intermediate step called Classify And Group (CAG), is shown below. CAG is also known as the more vague phrase; “requirements scrubbing”. As shown below, the intent is to remove as much ambiguity and inconsistency as possible by: 1) intelligently grouping the “shalls” into classification categories; 2) restructuring the result into a more usable artifact for the next downstream STF allocation step in the process.

The figure below shows the position of the (usually “hidden” and unaccounted for) CAG process within the allocation tree. Notice the connection between the CAG and the customer. The purpose of that interface is so that the customer can clarify meaning and intent to the person or persons performing the CAG work. If the people performing the CAG work aren’t allowed, or can’t obtain, access to the customer group that produced the initial set of “shalls”, then all may be lost right out of the gate. Misunderstandings and ambiguities will be propagated downstream and end up embedded in the fabric of the product. Bummer city.

Once the CAG effort is completed (after several iterations involving the customer(s) of course), the first allocation activity, Shall-To-Function (STF), can then be effectively performed. The figure below shows the initial state of two different approaches prior to commencement of the STF activity. In the top portion of the figure, CAG was performed prior to starting the STF. In the bottom portion, CAG was not performed. Which approach has a better chance of downstream success? Does your company’s formal product development process explicitly call out and describe a CAG step? Should it?

Functional Allocation V

Holy cow! We’re up to the fifth boring blarticle that delves into the mysterious nature of “Functional Allocation”. Let’s start here with the hypothetical 6 level allocation reference tree that was presented earlier.

Assume that our company is smart enough to define and standardize a reference tree like this one in their formal process documentation. Now, let’s assume that our company has been contracted to develop a Large And Complex (LAC) software-intensive system. My fuzzy and un-rigorous definition of large and complex is:

“The product has, (or will have after it’s built) lots of parts, many different kinds of parts, lots of internal and external interfaces, and lots of different types of interfaces”.

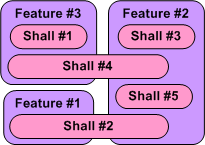

The figure below shows a partial result of step one in the multi-level process; the Shall-To-Feature (STF) allocation process. Given a set of 5 customer-supplied abstract “shalls”, someone has made the design decisions that led to the identification and definition of 3 less-abstract features that the product must provide in order to satisfy the customer shalls.We’ve started the movement from the abstract to the less abstract.

Just imagine what the model below would look like in the case where we had 100s of shalls to wrestle with. How could anyone possibly conclude up front that the set of shalls have been completely covered by the feature set? At this stage of the game, I assert that you can’t. You have to make a commitment and move on. In all likelihood, the initial STF allocation result won’t work. Thus, if your process doesn’t explicitly include the concept of “iterating on mistakes made and on new knowledge gained” as the product development process lurches forward, you’ll get what you deserve.

Note that in the simple example above, there is no clean and proper one-to-one STF mapping and there are 2 cross-cutting “shalls”. Also, note that there is no logical rule or mathematical formula grounded in physics that enables a shallocator (robot or human) to mechanically compute an “optimum” feature set and perform the corresponding STF allocation. It’s abstract stuff, and different qualified people will come up with different designs. Management, take heed of that fact.

So, given the initial finished STF allocation output (recorded and made accessible and visible for others to evaluate, of course) how was it arrived at? Could the effort be codified in a step-by-step Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) so that it can be classified as “repeatable and predictable”? I say no, regardless of what bureaucrats and process managers who’ve never done it themselves think. What about you, what do you think?