Archive

What’s REALLY Required

An understanding and application of “Systems Thinking” are pre-requisites to effective leadership in any large socio-technical group endeavor. Since business schools and pundits teach so-called business skills in disconnected, specialized, fragmented chunks and the primary component of systems thinking is the opposite of this classically entrenched Descartesian way of thinking, effective large scale leadership is nowhere to be found except in rare, small pockets of brilliance.

Systems thinking employs analytical thinking as a subordinate to its opposite – synthetic thinking. Since most (the vast majority of?) elite execs intentionally fragment their time to match their thinking style and they don’t know how to synthesize anything but an inflated and infallible image of themselves, they’re eternally stuck in the quagmire of one dimensional analytical thinking without a clue. But hey, ya gotta give them credit for knowing how to stuff their pockets with greenbacks.

D4P And D4F

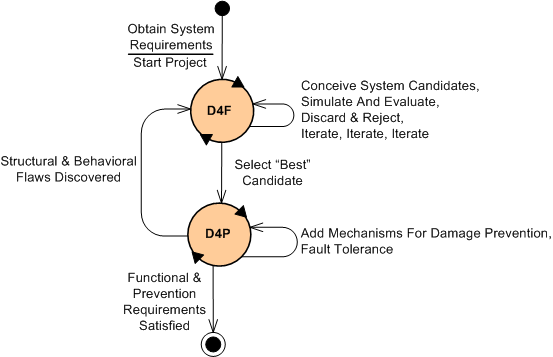

As some of you may know, my friend Bill Livingston recently finished writing his latest book, “Design For Prevention” (D4P). While doodling and wasting time (if you hadn’t noticed, I like to waste time), I concocted an idea for supplementing the D4P with something called “Design For Function” (D4F). The figure below shows, via a state machine diagram, the proposed marriage of the two complementary processes.

After some kind of initial problem definition is formulated by the owner(s) of the problem, the requirements for a “future” socio-technical system whose purpose is to dissolve the problem are recorded and “somehow” awarded to an experienced problem solver in the domain of interest. Once this occurs, the project is kicked off (Whoo Hoo!) and the wheels start churning via entry into the D4F state. In this state, various structures of connected functions are conceived and investigated for fitness of purpose. This iterative process, which includes short-cycle-run-break-fix learning loops via both computer-based and mental simulations, separates the wheat from the chaff and yields an initial “best” design according to some predefined criteria. Of course, adding to the iterative effort is the fact that the requirements will start changing before the ink dries on the initial snapshot.

Once the initial design candidate is selected for further development, the sibling D4P state is entered for the first (but definitely not last) time. In this important but often neglected problem solving system sub-state, the problem solution system candidate is analyzed for failure modes and their attendant consequences. Additional monitoring and control functional structures are then conceived and integrated into the system design to prevent failures and mitigate those failures that can’t be prevented. The goal at this point is to make the system fault tolerant and robust to large, but low probability, external and internal disturbances. Again, iterative simulations are performed as reconnaissance trips into the future to evaluate system effectiveness and robustness before it gets deployed into its environment.

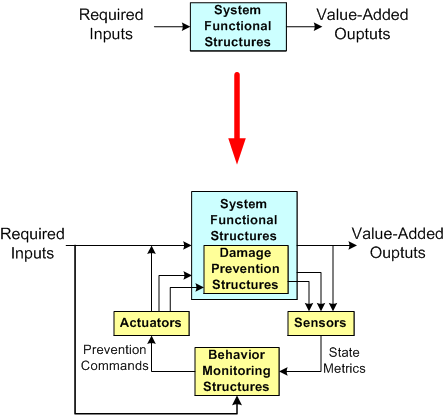

The figure below shows a dorky model of a system design before and after the D4P process has been executed. Notice the necessary added structural and behavioral complexity incorporated into the system as a result of recursively applying the D4P. Also note that the “Behavior Monitoring” structure(s), be they composed of people in a social system or computers in an automated system, or most likely both, need to have an understanding of the primary system goal seeking functions in order to effectively issue damage prevention and mitigation instructions to the various system elements. Also note that these instructions need not only be logically correct, they need to be timely for them to be effective. If the time lag between real-time problem sensing and control actuating is too great (which happens repeatedly and frequently in huge multi-layered command and control hierarchies that don’t have or want an understanding of what goes on down in the dirty boiler room), then the internal/external damage caused by the system can be as devastating as a cheaper, less complex system operating with no damage prevention capability at all.

So what do you think? Is this D4F + D4P process viable? A bunch of useless baloney?

Machine Age Thinking, Systems Age Thinking

In Ackoff’s Best, Mr. Russell Ackoff states the following

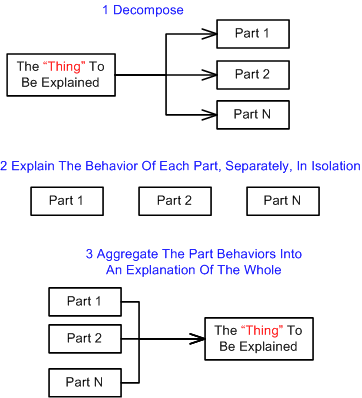

…Machine-Age thinking: (1) decomposition of that which is to be explained, (2) explanation of the behavior or properties of the parts taken separately, and (3) aggregating these explanations into an explanation of the whole. This third step, of course, is synthesis.

The figure below models the classical machine age, mechanistic thinking process described by Ackoff. The problem with this antiquated method of yesteryear is that it doesn’t work very well for systems of any appreciable complexity – especially large socio-technical systems (every one of which is mind-boggingly complex). During the decomposition phase, the interactions between the parts that animate the “thing to be explained” are lost in the freakin’ ether. Even more importantly, the external environment in which the “thing to be explained” lives and interacts is nowhere to be found. This is a huge mistake because the containing environment always has a profound effect on the behavior of the system as a whole.

Mr. Ackoff professes that the antidote to mechanistic thinking is……. system thinking (duh!):

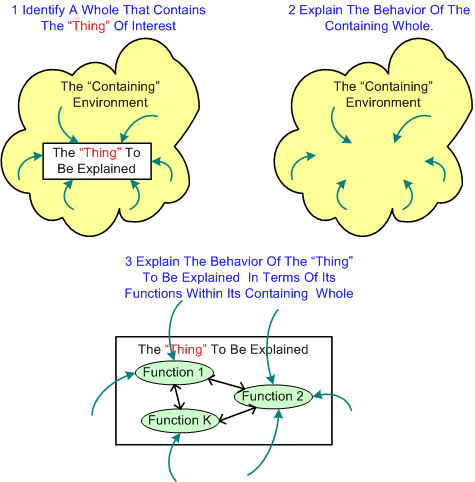

In the systems approach there are also three steps:

1. Identify a containing whole (system) of which the thing to be explained is a part.

2. Explain the behavior or properties of the containing whole.

3. Then explain the behavior or properties of the thing to be explained in terms of its role(s) or function(s) within its containing whole.

Note that in this sequence, synthesis precedes analysis.

The figure below graphically depicts the systems thinking process. Note that the relationships between the “thing to be explained” and its containing whole are first class citizens in this mode of thinking.

One of the primary reasons why we seek to understand systems is so that we can diagnose and solve problems that arise within established systems; or to design new systems to solve problems that need to be controlled or ameliorated. By applying the wrong thinking style to a system problem, the cure often ends up being worse than the disease. D’oh!

One of the primary reasons why we seek to understand systems is so that we can diagnose and solve problems that arise within established systems; or to design new systems to solve problems that need to be controlled or ameliorated. By applying the wrong thinking style to a system problem, the cure often ends up being worse than the disease. D’oh!