Archive

Functional Allocation VIII

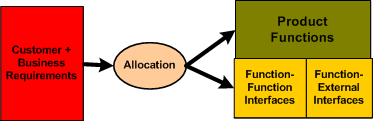

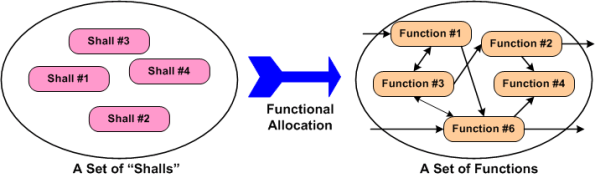

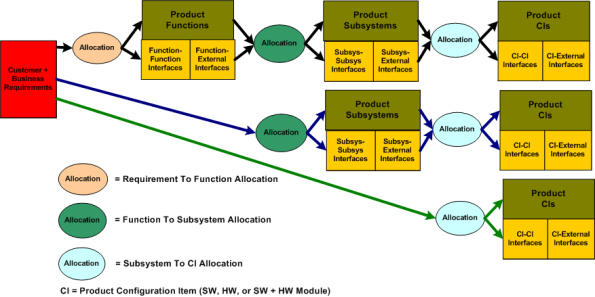

Typically, the first type of allocation work performed on a large and complex product is the shall-to-function (STF) allocation task. The figure below shows the inputs and outputs of the STF allocation process. Note that it is not enough to simply identify, enumerate, and define the product functions in isolation. An integral sub-activity of the process is to conjure up and define the internal and external functional interfaces. Since the dynamic interactions between the entities in an operational system (human or inanimate) give the system its power, I assert that interface definition is the most important part of any allocation process.

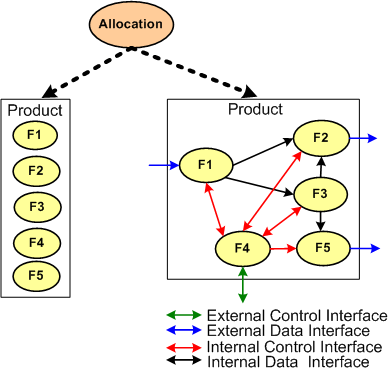

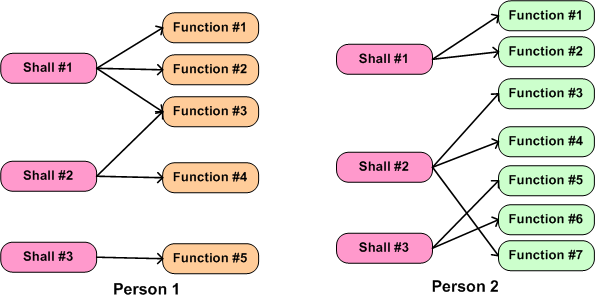

The figure below illustrates two alternate STF allocation outputs produced by different people. On the left, a bland list of unconnected product functions have been identified, but the functional structure has not been defined. On the right, the abstract functional product structure, defined by which functions are required to interact with other functions, is explicitly defined.

If the detailed design of each product function will require specialized domain expertise, then releasing a raw function list on the left to the downstream process can result in all kinds of counter productive behavior between the specialists whose functions need to communicate with each other in order to contribute to the product’s operation. Each function “owner” will each try to dictate the interface details to the “others” based on the local optimization of his/her own functional piece(s) of the product. Disrespect between team members and/or groups may ensue and bad blood may be spilled. In addition, even when the time consuming and contentious interface decision process is completed, the finished product will most likely suffer from a lack of holistic “conceptual integrity” because of the multitude of disparate interface specifications.

It is the lead system engineer’s or architect’s duty to define the function list and the interfaces that bind them together at the right level of detail that will preserve the conceptual integrity of the product. The danger is that if the system design owner goes too far, then the interfaces may end up being over-constrained and stifling to the function designers. Given a choice between leaving the interface design up to the team or doing it yourself, which approach would you choose?

Functional Allocation VII

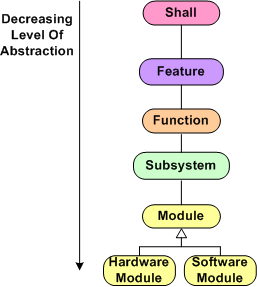

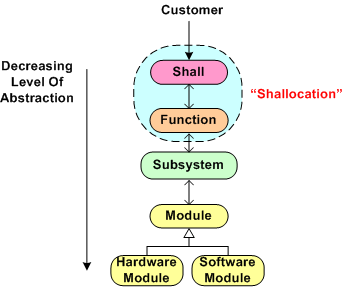

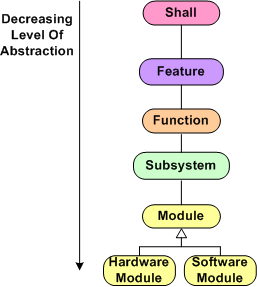

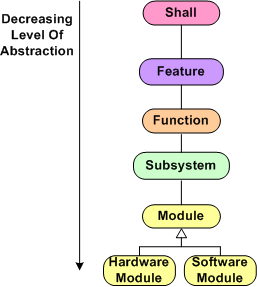

Here we are at blarticle number 7 on the unglamorous and boring topic of “Functional Allocation”. Once again, for a reference point of discussion, I present the hypothetical allocation tree below (your company does have a guidepost like this, doesn’t it?). In summary, product “shalls” are allocated to features, which are allocated to functions, which are allocated to subsystems, which are allocated to software and hardware modules. Depending on the size and complexity of the product to be built, one or more levels of abstraction can be skipped because the value added may not be worth the effort expended. For a simple software-only system that will run on Commercial-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) hardware, the only “allocation” work required to be performed is a shall-to-software module mapping.

During the performance of any intellectually challenging human endeavor, mistakes will be made and learning will take place in real-time as the task is performed. That’s how fallible humans work, period. Thus for the output of such a task like “allocation” to be of high quality, an iterative and low latency feedback loop approach should be executed. When one qualified person is involved, and there is only one “allocation” phase to be performed (e.g. shall-to-module), there isn’t a problem. All the mistake-making, learning, and looping activity takes place within a single mind at the speed of thought. For (hopefully) long periods of time, there are no distractions or external roadblocks to interrupt the performance of the task.

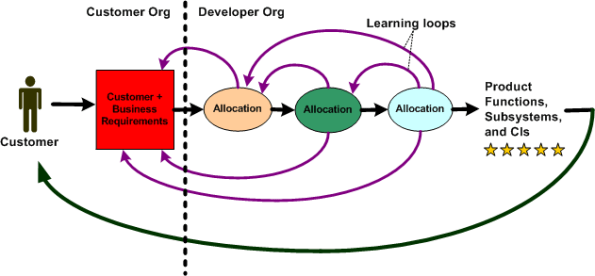

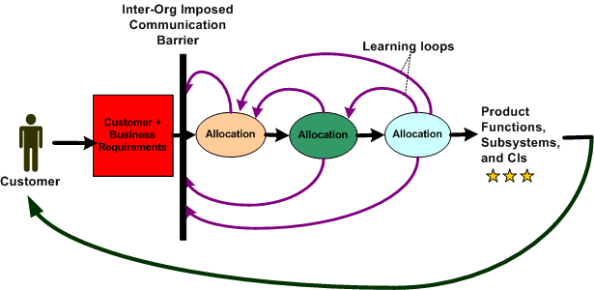

For a big and complex multi-technology product where multiple levels of “allocation” need to be performed and multiple people and/or specialized groups need to be involved, all kinds of socio-technical obstacles and roadblocks to downstream success will naturally emerge. The figure below shows an effective product development process where iteration and loop-based learning is unobstructed. Communication flows freely between the development groups and organizations to correct mistakes and converge on an effective solution . Everything turns out hunky dory and the customer gets a 5 star product that he/she/they want and the product meets all expectations.

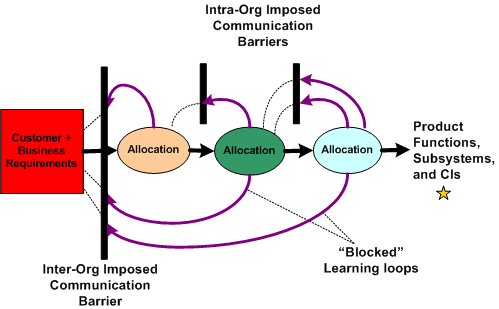

The figure below shows a dysfunctional product development process. For one reason or another, communication feedback from the developer org’s “allocation” groups is cut off from the customer organization. Since questions of understanding don’t get answered and mistakes/errors/ambiguities in the customer requirements go uncorrected, the end product delivered back to the customer underperforms and nobody ends up very happy. Bummer.

The figure below illustrates the worst possible case for everybody involved – a real mess. Not only do the customer and developer orgs not communicate; the “allocation” groups within the developer org don’t, or are prohibited from, communicating effectively with each other. The product that emerges from such a sequential linear-think process is a real stinker, oink oink. The money’s gone. the time’s gone, and the damn thang may not even work, let alone perform marginally.

Obviously, this situation is a massive failure of corpo leadership and sadly, I assert that it is the norm across the land. It is the norm because almost all big customer and developer orgs are structured as hierarchies of rank and stature with “standard” processes in place that require all kinds and numbers of unqualified people to “be in the loop” and approve (disapprove?) of every little step forward – lest their egos be hurt. Can a systemic, pervasive, baked-in problem like this be solved? If so, who, if anybody, has the ability to solve it? Can a single person overcome the massive forces of nature that keep a hierarchical ecosystem like this viable?

“The Biggest problem To Communication Is The Illusion That It Has Taken Place.” – George Bernard Shaw

Functional Allocation VI

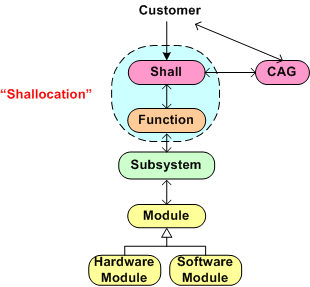

Every big system, multi-level, “allocation” process (like the one shown below) assumes that the process is initialized and kicked-off with a complete, consistent, and unambiguous set of customer-supplied “shalls”. These “shalls” need to be “shallocated” by a person or persons to an associated aggregate set of future product functions and/or features that will solve, or at least ameliorate, the customer’s problem. In my experience, a documented set of “shalls” is always provided with a contract, but the organization, consistency, completeness, and understandability of these customer level requirements often leaves much to be desired.

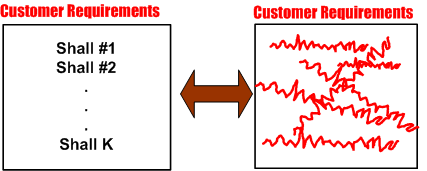

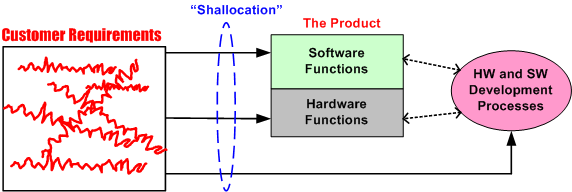

The figure below represents a hypothetical requirements mess. The mess might have been caused by “specification by committee”, where a bunch of people just haphazardly tossed “shalls” into the bucket according to different personal agendas and disparate perceptions of the problem to be solved.

Given a fragmented and incoherent “mess”, what should be done next? Should one proceed directly to the Shall-To-Function (STF) process step? One alternative strategy, the performance of an intermediate step called Classify And Group (CAG), is shown below. CAG is also known as the more vague phrase; “requirements scrubbing”. As shown below, the intent is to remove as much ambiguity and inconsistency as possible by: 1) intelligently grouping the “shalls” into classification categories; 2) restructuring the result into a more usable artifact for the next downstream STF allocation step in the process.

The figure below shows the position of the (usually “hidden” and unaccounted for) CAG process within the allocation tree. Notice the connection between the CAG and the customer. The purpose of that interface is so that the customer can clarify meaning and intent to the person or persons performing the CAG work. If the people performing the CAG work aren’t allowed, or can’t obtain, access to the customer group that produced the initial set of “shalls”, then all may be lost right out of the gate. Misunderstandings and ambiguities will be propagated downstream and end up embedded in the fabric of the product. Bummer city.

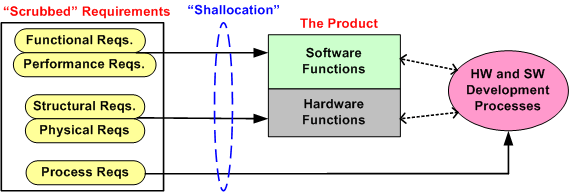

Once the CAG effort is completed (after several iterations involving the customer(s) of course), the first allocation activity, Shall-To-Function (STF), can then be effectively performed. The figure below shows the initial state of two different approaches prior to commencement of the STF activity. In the top portion of the figure, CAG was performed prior to starting the STF. In the bottom portion, CAG was not performed. Which approach has a better chance of downstream success? Does your company’s formal product development process explicitly call out and describe a CAG step? Should it?

Functional Allocation V

Holy cow! We’re up to the fifth boring blarticle that delves into the mysterious nature of “Functional Allocation”. Let’s start here with the hypothetical 6 level allocation reference tree that was presented earlier.

Assume that our company is smart enough to define and standardize a reference tree like this one in their formal process documentation. Now, let’s assume that our company has been contracted to develop a Large And Complex (LAC) software-intensive system. My fuzzy and un-rigorous definition of large and complex is:

“The product has, (or will have after it’s built) lots of parts, many different kinds of parts, lots of internal and external interfaces, and lots of different types of interfaces”.

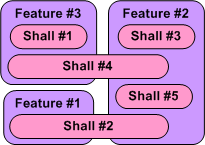

The figure below shows a partial result of step one in the multi-level process; the Shall-To-Feature (STF) allocation process. Given a set of 5 customer-supplied abstract “shalls”, someone has made the design decisions that led to the identification and definition of 3 less-abstract features that the product must provide in order to satisfy the customer shalls.We’ve started the movement from the abstract to the less abstract.

Just imagine what the model below would look like in the case where we had 100s of shalls to wrestle with. How could anyone possibly conclude up front that the set of shalls have been completely covered by the feature set? At this stage of the game, I assert that you can’t. You have to make a commitment and move on. In all likelihood, the initial STF allocation result won’t work. Thus, if your process doesn’t explicitly include the concept of “iterating on mistakes made and on new knowledge gained” as the product development process lurches forward, you’ll get what you deserve.

Note that in the simple example above, there is no clean and proper one-to-one STF mapping and there are 2 cross-cutting “shalls”. Also, note that there is no logical rule or mathematical formula grounded in physics that enables a shallocator (robot or human) to mechanically compute an “optimum” feature set and perform the corresponding STF allocation. It’s abstract stuff, and different qualified people will come up with different designs. Management, take heed of that fact.

So, given the initial finished STF allocation output (recorded and made accessible and visible for others to evaluate, of course) how was it arrived at? Could the effort be codified in a step-by-step Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) so that it can be classified as “repeatable and predictable”? I say no, regardless of what bureaucrats and process managers who’ve never done it themselves think. What about you, what do you think?

Functional Allocation IV

Part IV is a continuation of our discussion regarding the often misunderstood and ill-defined process of “functional allocation”. In this part we’ll, explore the nature of the “shallocation” task, some daunting organizational obstacles to its successful completion, and the dependency of quality of output on the specific persons assigned (or allocated?) to the task.

If you can find one, the process description of functional allocation starts out assuming that a human allocator is given a linear text list, which maybe quite large, of “shalls” supplied by an external customer or internal customer advocate. Of course, these “shalls” are also assumed to be unambiguous, consistent, non-contradictory, complete, and intelligently organized (yeah, right).

My personal experience has been that the “shalls” are usually strewn all over the place and the artifact that holds them is severely lacking in what Fred Brooks called “conceptual integrity”. Sometimes, the “shalls” seem to randomly jump back and forth from high level abstractions down to physical properties – a mixed mess hacked together by a group of individuals with different agendas. In addition, some customers (especially government bureaucracies) often impose some overconstraining “shalls” on the structure of the development team and the processes that the team is required to use during the development of the solution to their problem (control freaks). Even worse, in order to project a false image of “we know what we’re doing” infallibility and the fact that they don’t have to do the hard value-creation work themselves, helpful managers of developer orgs often discourage, or downright prevent, clarification questions from being asked of the customer by development team members. All communciations must be filtered through the “proper” chain of command, regardless of how long it takes or whether technical questions get filtered and distorted to incomprehensibilty through non-technical wonks with a fancy title. Bummer.

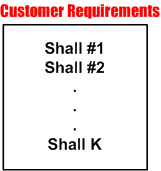

Because we want to move forward with this discussion, assume the unassume-able; the customer “shall” list is perfectly complete and understood by the developer org’s system engineers. What’s next? The figure below shows the “initialization” state. The perfect list of “shalls” must be shallocated to a set of non-existent product functions. Someone, somehow, has got to conceive of and define the set of functions and the logical inter-function connectivity that will satisfy the perfectly clear and complete “shalls” list.

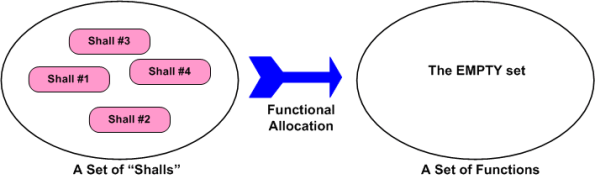

Piece of cake, right? The task of shallocation is so easy and well described by many others (yeah, right), that I won’t even waste any e-space giving the step by step recipe for it. The figure below shows the logical functional structure of the product after the trivial shallocation process is completed by a robot or an expensive automated software tool.

Realistically, in today’s world the shallocation process can’t be automated away, and it’s highly person-specific. As the example in the figure below shows, given the same set of “shalls”, two different people will, “after a miracle occurs”, likely conjure up a different set of functions in an attempt to meet the customer’s product requirements. Not only can the number of functions, and the internal nature of each function be different, the allocation of shalls-to-functions may be different. Expecting a pristine, one-to-one shall-to-function mapping is unrealistically utopian.

What the example below doesn’t show is the person-specific creation of the inter-function logical connectivity (see the right portion of the previous figure) that is required for the product system to “work”. After all, a set of unconnected functions, much like a heap of car parts, doesn’t do anything but sit there looking sophisticated. It’s the interactions between the functions during operation that give a product it’s power to maybe, just maybe, solve a customer’s problem.

The purpose of part IV in this seemingly endless series of blarticles on “functional allocation” was to basically point out the person-specific nature of the first step in a multi-level nested allocation process. It also hinted at some obstacles that conspire to thwart the effective performance of the task of shallocation.

Functional Allocation III

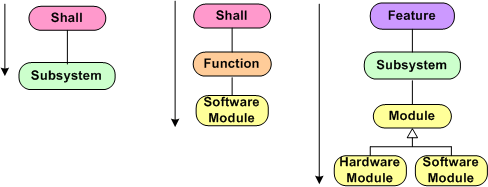

The figure below shows the movement from the abstract to the concrete through a nested “allocation” process designed for big and complex products (thus, hackers and duct-tapers need not apply). “Shalls” are allocated to features, which are allocated to functions, which are allocated to subsystems, which are allocated to hardware and software modules. Since allocation is labor intensive, which takes time, which takes money, are all four levels of allocation required? Can’t we just skip all the of the intermediate levels, allocate “shalls” to HW/SW modules, and start iteratively building the system pronto? Hmmm. The answer is subjective and, in addition to product size/complexity, it depends on many corpo-specific socio-technical factors. There is no pat answer.

The figure below shows three variations derived from the hypothetical six-level allocation reference template. In the left-most process, two or more product subsystems that will (hopefully) satisfy a pre-existing set of “shalls” are conceived. At the end of the allocation process, the specification artifacts are released to teams of people “allocated” to each subsystem and the design/construction process continues. In the middle process, each SW module, along with the set of shalls and functions that it is required to implement is allocated to a SW developer. In the right process, which, in addition to custom software requires the creation of custom HW, the specification artifacts are allocated to various SW and HW engineers. (Since multiple individuals are involved in the development of the product, the definition of all entity-to-entity interfaces is at least as crucial as the identification and definition of the entities themselves, but that is a subject for another future post.)

Which process variation, if any, is “best”? Again, the number of unquantifiable socio-technical factors involved can make the decision daunting. The sad part is, in order to avoid thinking and making a conscious decision, most corpo orgs ram the full 6 level process down their people’s throats no matter what. To pour salt on the wound, management, which is always on the outside and looking-in toward the development teams, piles on all kinds of non-value-added byzantine approval procedures while simultaneously pounding the team(s) with schedule pressure to compplete. If you’re on the inside and directly creating or indirectly contributing to value creation, it’s not pretty. Bummer.

Functional Allocation II

Assume that you’re lucky and your company has a standard, generic product breakdown structure as follows:

- Product

- Functions

- Subsystems

- Configuration Items (Hardware and Software modules)

In order to achieve business success, an operating product needs to perform the functions that a user needs or wants for some reason. The functions are implemented by the number of, and interconnections between, the product subsystems. The subsystems are comprised of the hardware and software modules that animate the product.

Depending on the complexity of the new product that is required to be developed, between one and three “allocation” paths from concept to product can be pursued. The figure below shows these paths.

If the problem that the product is required to control or solve is simple, the relatively short bottom path can be selected. If the finished aggregation of CIs do their intended job of seamlessly and elegantly supplying users with the functionality that they want/need, then the product will, in all likelihood, be successful. Profits will flow and customers will be happy. Classic win-win.

If the problem is complex, then the top path should be followed. Consciously or unconsciously pursuing the bottom path for complex products can, and usually is, disasterous. At best, money will be lost. At worst, people can die as a result of the end product’s failure to do what it was intended to do. Even if the top path is correctly chosen, failure to execute the process effectively can produce the same result as choosing the wrong bottom path. For success, the product and the “allocation” process must match. Success won’t be guaranteed, but the likelihood of success will increase.

So, what can cause a business failure even when the product and process are correctly matched at the outset? The list of reasons is long. Here are just a few that come to mind:

- Technical incompetence

- Managerial incompetence

- Massive external or internal schedule pressure that leads to corner-cutting

- Inter and/or intra-group rivalries naturally encouraged by hierarchically structured organizations of rank and privilege.

- An unfair reward system

- An obsession with following a rigid, micro-prescribed process to the letter of the law (dotting all the i’s and crossing all the t’s)

In summary, a product-process mismatch virtually guarantees long term business failure, but a product-process match may, just may, result in business success. The odds seem to be stacked in favor of failure. Bummer.

Functional Allocation I

Some system engineering process descriptions talk about “Functional Allocation” as being one of the activities that is performed during product development. So, what is “Functional Allocation”? Is it the allocation of a set of interrelated functions to a set of “something else”? Is it the allocation of a set of “something else” to a set of function(s)? Is it both? Is it done once, or is it done multiple times, progressing down a ladder of decreasing abstraction until the final allocation iteration is from something abstract to something concrete and physically measurable?

I hate the word “allocation”. I prefer the word “design” because that’s what the activity really is. Given a specific set of items at one level of abstraction, the “allocator” must create a new set of items at the next lower level of abstraction. That seems like design to me, doesn’t it? Depending on the nature and complexity of the product under development, conjuring up the next lower level set of items may be very difficult. The “allocator” has an infinite set of items to consciously choose from and purposefully interconnect. “Allocation” implies a bland, mechanistic, and deterministic procedure of apportioning one set of given items to another different set of given items. However, in real life only one set of items is “given” and the other set must be concocted out of nowhere.

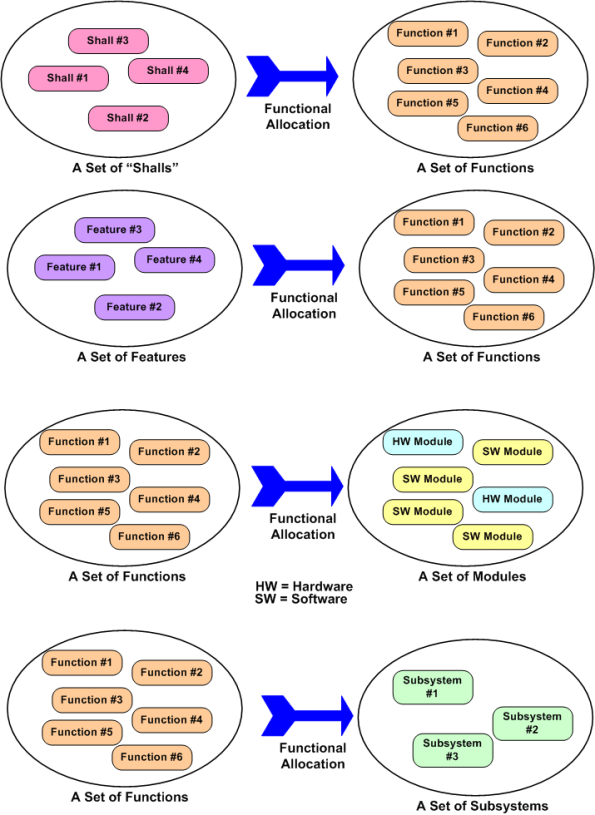

The figure below shows four different types of functional allocations: shalls-to-functions, features-to-functions, functions-to-modules, and functions-to-subsystems. Each allocation example has a set of functions involved. In the first two examples, the set of functions have been allocated “to”, and in the last two examples, the set of functions have been allocated “from”.

So, again I ask, what is functional allocation? To managers who love to remove people from the loop and automate every activity they possibly can to reduce costs, can human beings ever be removed from the process of functional allocation? If you said no, then what can you do to help make the process of allocation more efficient?