Archive

Requirements Before, Design After

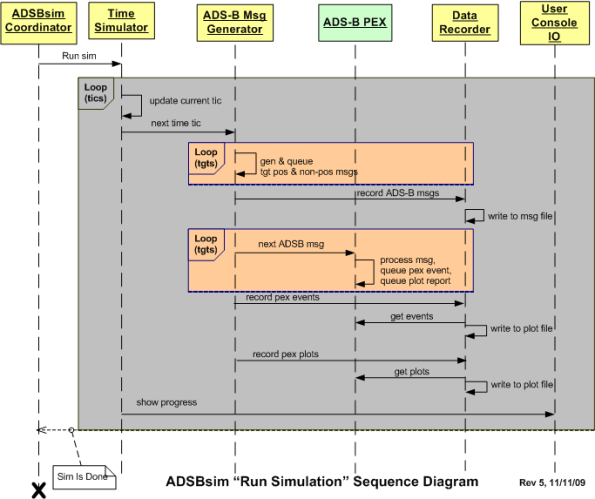

The figure below depicts a UML sequence diagram of the behavior of a simulator during the execution of a user defined scenario. Before the code has been written and tested, one can interpret this diagram as a set of interrelated behavioral requirements imposed on the software. After the code has been written, it can be considered a design artifact that reflects what the code does at a higher level of abstraction than the code itself.

Interpretations like this give credence to Alan Davis’s brilliant quote:

One man’s requirement is another man’s design

Here’s a question. Do you think that specifying the behavior requirements in the diagram would have been best conveyed via a user story or a use case description?

Here’s a question. Do you think that specifying the behavior requirements in the diagram would have been best conveyed via a user story or a use case description?

Partial Training

If you’re gonna spend money on training your people, do it right or don’t do it at all.

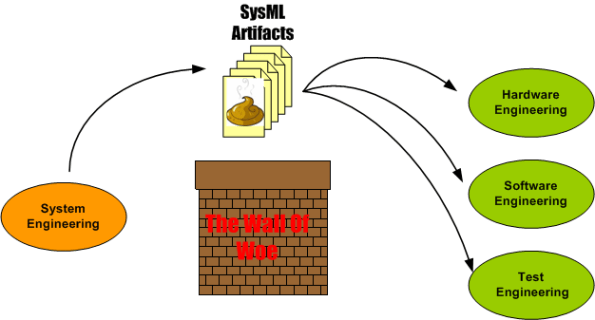

Assume that a new project is about to start up and the corpo hierarchs decide to use it as a springboard to institutionalizing SysML into its dysfunctional system engineering process. The system engineering team is then sent to a 3 day SysML training course where they get sprayed by a fire hose of detailed SysML concepts, terminology, syntax, and semantics.

Armed with their new training, the system engineering team comes back, generates a bunch of crappy, incomplete, ambiguous, and unhelpful SysML artifacts, and then dumps them on the software, hardware, and test teams. The receiving teams, under the schedule gun and not having been trained to read SysML, ignore the artifacts (while pretending otherwise) and build an unmaintainable monstrosity that just barely works – at twice the cost they would would have spent if no SysML was used. The hierarchs, after comparing product development costs before and after SysML training, declare SysML as a failure and business returns to the same old, same old. Bummer.

The Requirements Landscape

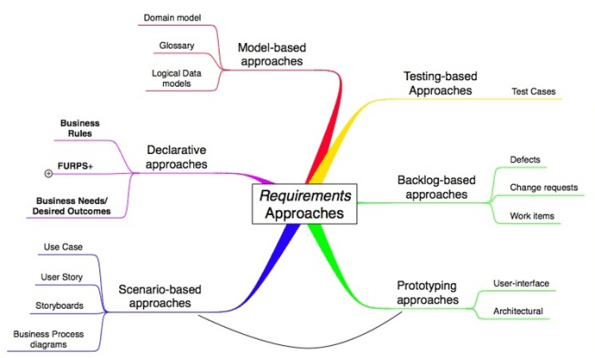

Kurt Bittner, of Ivar Jacobson International, has written a terrific white paper on the various approaches to capturing requirements. The mind map below was copied and pasted from Kurt’s white paper.

In his paper, Bittner discusses the pluses and minuses of each of his defined approaches. For the text-based “declarative” approaches, he states the pluses as: “they are familiar” and “little specialized training” is needed to write them. Bittner states the minuses as:

- They are “poor at specifying flow behavior”

- It’s “hard to connect related requirements”

IMHO, as systems get more and more complex, these shortcomings lead to bigger and bigger schedule, cost, and quality shortfalls. Yet, despite the advances in requirements specification methodologies nicely depicted in Bittner’s mind map, defense/aerospace contractors and their bureaucratic government customers seem to be forever married to the text-based “shall” declarative approach of yesteryear. Dinosaur mindsets, the lack of will to invest in corpo-wide training, and expensive past investments in obsolete and entrenched text-based requirements tools have prevented the newer techniques from gaining much traction. Do you think this encrusted way of specifying requirements will change anytime soon?

Shallmeisters, Get Over It.

If you pick up any reference article or book on requirements engineering, I think you’ll find that most “experts” in the field don’t obsess over “shalls”. They know that there’s much more to communicating requirements than writing down tidy, useless, fragmented, one line “shall” statements. If you don’t believe me, then come out of your warm little cocoon and explore for yourself. Here are just a few references:

http://www.amazon.com/Process-System-Architecture-Requirements-Engineering/dp/0932633412/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1257672507&sr=1-3

With the growing complexity of software-intensive systems that need to be developed for an org to remain sustainable and relevant, the so-called venerable “shall” is becoming more and more dinosaurish. Obviously, there will always be a place for “shalls” in the development process, but only at the most superficial and highest level of “requirements specification”; which is virtually useless to the hardware, software, network, and test engineers who have to build the system (while you watch from the sidelines and “wait” until the wrong monstrosity gets built so you can look good criticizing it for being wrong).

So, what are some alternatives to pulling useless one dimensional “shalls” out of your arse? How about mixing and matching some communication tools from this diversified, two dimensional menu:

- UML Class diagrams

- UML Use Case diagrams

- UML Deployment diagrams

- UML Activity diagrams

- UML State Machine diagrams

- UML Sequence diagrams

- Use Case Descriptions

- User Stories

- IDEF0 diagrams

- Data Flow Diagrams

- Control Flow Diagrams

- Entity-Relationship diagrams

- SysML Block Definition diagrams

- SysML Internal Block Definition diagrams

- SysML Requirements diagrams

- SysML Parametric diagrams

Get over it, add a second dimension to your view, move into this century, and learn something new. If not for your company, then for yourself. As the saying goes, “what worked well in the past might not work well in the future”.

What The Hell’s A Unit?

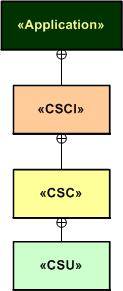

- CSCI = Computer Software Configuration Item

- CSC = Computer Software Component

- CSU = Computer Software Unit

In my industry (aerospace and defense), we use the abstract, programming-language-independent terms CSCI, CSC, and CSU as a means for organizing and conversing about software architectures and designs. The terms go way back, and I think (but am not sure) that someone in the Department Of Defense originally conjured them up.

The SysML diagram below models the semantic relationships between these “formal” terms. An application “contains” one or more CSCIs, each of which which contains one or more CSCs, each of which contains one or more CSUs. If we wanted to go one level higher, we could say that a “system” contains one or more Applications.

In my experience, the CSCI-CSC-CSU tree is almost never defined and recorded for downstream reference at project start. Nor is it evolved or built-up as the project progresses. The lack of explicit definition of the CSCs and, especially the CSUs, has often been a continuous source of ambiguity, confusion, and mis-communication within and between product development teams.

“The biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” – George Bernard Shaw.

A consequence of not classifying an application down to the CSU level is the classic “what the hell’s a unit?” problem. If your system is defined as just a collection of CSCIs comprised of hundreds of thousands of lines of source code and the identification of CSCs and CSUs is left to chance, then a whole CSCI can be literally considered a “unit” and you only have one unit test per CSCI to run (LOL!)

In preparation for an idea that follows, check out the language-specific taxonomies that I made up (I like to make stuff up so people can rip it to shreds) for complex C++ and Java applications below. If your app is comprised of a single, simple process without any threads or tasks (like they teach in school and intro-programming books), mentally remove the process and thread levels from the diagram. Then just plop the Application level right on top of the C++ namespace and/or the Java package levels.

To solve, or at least ameliorate the “what the hell’s a unit?” problem, I gently propose the consideration of the following concrete-to-abstract mappings for programs written in C++ and Java. In both languages, each process in an application “is a” CSCI and each thread within a process “is a” CSC. A CSU “is a” namespace (in C++) or a package (in Java).

I think that adopting a map such as this to use as a standard communication tool would lead to fewer mis-communications between and among development team members and, more importantly, between developer orgs and customer orgs that require design artifacts to employ the CSCI/CSC/CSU terminology.

As just stated, the BD00 proposal maps a C++ namespace or a java package into the lowest level element of abstract organization – the CSU. If that level of granularity is too coarse, then a class, or even a class member function (method in Java), can be designated as a CSU (as shown below). The point is that each company’s software development organization should pick one definition and use it consistently on all their projects. Then everyone would have a chance of speaking a common language and no one would be asking, “what the hell’s a freakin’ unit?“.

So, “What the hell’s a unit?” in your org? A member function? A class? A namespace? A thread? A process? An application? A system?

Useless Cases

Despite the blasphemous title of this blarticle, I think that “use cases” are a terrific tool for capturing a system’s functional requirements out of the ether; for the right class of applications. Nevertheless, I agree with requirements “expert” Karl Wiegers, who states the following in “More About Software Requirements: Thorny Issues And Practical Advice“:

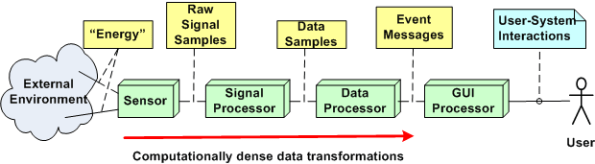

However, use cases are less valuable for projects involving data warehouses, batch processes, hardware products with embedded control software, and computationally intensive applications. In these sorts of systems, the deep complexity doesn’t lie in the user-system interactions. It might be worthwhile to identify use cases for such a product, but use case analysis will fall short as a technique for defining all the system’s behavior.

I help to define, specify, design, code, and test embedded (but relatively “big”) software-intensive sensor systems for the people-transportation industry. The figure below shows a generic, pseudo-UML diagram of one of these systems. Every component in the string is software-intensive. In this class of systems, like Karl says, “the deep complexity doesn’t lie in the user-system interactions”. As you can see, there’s a lot of special and magical “stuff” going on behind the GUI that the user doesn’t know about, and doesn’t care to know about. He/she just cares that the objects he/she wants to monitor show up on the screen and that the surveillance picture dutifully provided by the system is an accurate representation of what’s going on in the real world outside.

A list of typical functions for a product in this class may look like this:

- Display targets

- Configure system

- Monitor system operation

- Tag target

- Control system operation

- Perform RF signal filtering

- Perform signal demodulation

- Perform signal detection

- Perform false signal (e.g. noise) rejection

- Perform bit detection, extraction, and message generation

- Perform signal attribute (e.g. position, velocity) estimation

- Perform attribute tracking

Notice that only the top five functions involve direct user interaction with the product. Thus, I think that employing use cases to capture the functions required to provide those capabilities is a good idea. All the dirty and nasty”perform” stuff requires vertical, deep mathematical expertise and specification by sensor domain experts (some of whom, being “expert specialists”, think they are Gods). Thus, I think that the classical “old and unglamorous” Software Requirements Specification (SRS) method of defining the inputs/processing/output sequences (via UML activity diagrams and state machine diagrams) blows written use case descriptions out of the water in terms of Return On Investment (ROI) and value transferred to software developers.

Clueless Bozo Managers (BMs) and senior wannabe-a-BM developers who jump on the “use cases for everything” bandwagon (but may have never written a single use case description themselves) waste company time and money trying to bully “others” into ramming a square peg into a round hole. But they look hip, on the ball, and up to date doing it. And of course, they call it leadership.

Structure And The “ilities”

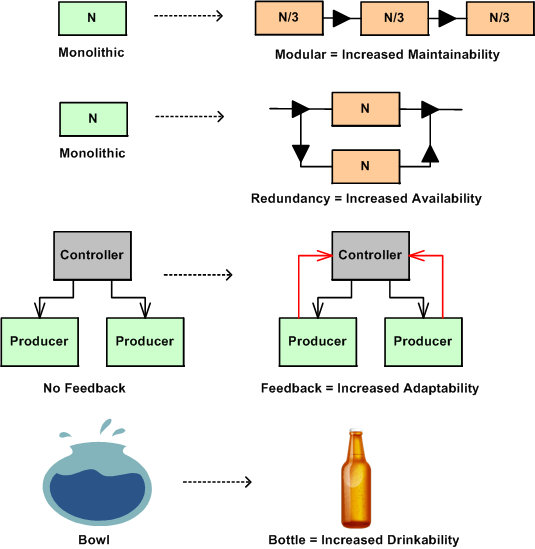

In nature, structure is an enabler or disabler of functional behavior. No hands – no grasping, no legs – no walking, no lungs – no living. Adding new functional components to a system enables new behavior and subtracting components disables behavior. Changing the arrangement of an existing system’s components and how they interconnect can also trade-off qualities of behavior, affectionately called the “ilities“. Thus, changes in structure effect changes in behavior.

The figure below shows a few examples of a change to an “ility” due to a change in structure. Given the structure on the left, the refactored structure on the right leads to an increase in the “ility” listed under the new structure. However, in moving from left to right, a trade-off has been made for the gain in the desired “ility”. For the monolithic->modular case, a decrease in end-to-end response-ability due to added box-to-box delay has been traded off. For the monolithic->redundant case, a decrease in buyability due to the added purchase cost of the duplicate component has been introduced. For the no feedback->feedback case, an increase in complexity has been effected due to the added interfaces. For the bowl->bottle example, a decrease in fill-ability has occurred because of the decreased diameter of the fill interface port.

The plea of this story is: “to increase your aware-ability of the law of unintended consequences”. What you don’t know CAN hurt you. When you are bound and determined to institute what you think is a “can’t lose” change to a system that you own and/or control, make an effort to discover and uncover the ilities that will be sacrificed for those that you are attempting to instill in the system. This is especially true for socio-technical systems (do you know of any system that isn’t a socio-technical system?) where the influence on system behavior by the technical components is always dwarfed by the influence of the components that are comprised of groups of diverse individuals.

Don’t Be Late!

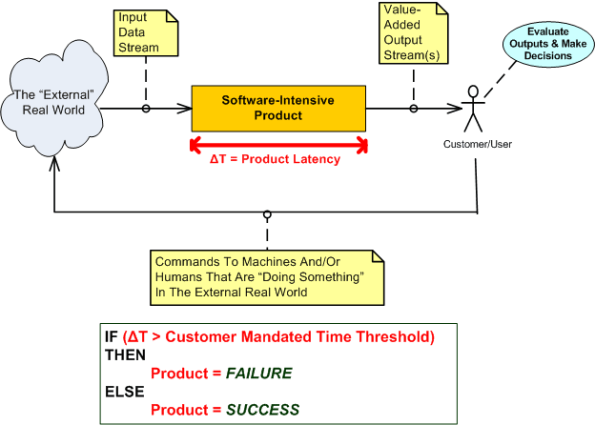

The software-intensive products that I get paid to specify, design, build, and test involve the real-time processing of continuous streams of raw input data samples. The sample streams are “scrubbed and crunched” in order to generate higher-level, human interpretable, value-added, output information and event streams. As the external stream flows into the product, some samples are discarded because of noise and others are manipulated with a combination standard and proprietary mathematical algorithms. Important events are detected by monitoring various characteristics of the intermediate and final output streams. All this processing must take place fast enough so that the input stream rate doesn’t overwhelm the rate at which outputs can be produced by the product; the product must operate in “real-time”.

The human users on the output side of our products need to be able to evaluate the output information quickly in order to make important and timely command and control decisions that affect the physical well-being of hundreds of people. Thus, latency is one of the most important performance metrics used by our customers to evaluate the acceptability of our products. Forget about bells and whistles, exotic features, and entertaining graphical interfaces, we’re talking serious stuff here. Accuracy and timeliness of output are king.

Latency (or equivalently, response time) is the time it takes from an input sample or group of related samples to traverse the transformational processing path from the point of entry to the point of egress through the software-dominated product “box” or set of interconnected boxes. Low latency is good and high latency is bad. If product latency exceeds a time threshold that makes the output effectively unusable to our customers , the product is unacceptable. In some applications, failure of the absolute worst case latency to stay below the threshold can be the deal breaker (hard real time) and in other applications the average latency must not exceed the threshold xx percent of the time where xx is often greater than 95% (soft real time).

Latency is one of those funky, hard-to-measure-until-the-product-is-done, “non-functional” requirements. If you don’t respect its power to make or break your wonderful product from the start of design throughout the entire development effort, you’ll get what you deserve after all the time and money has been spent – lots of rework, stress, and angst. So, if you work on real-time systems, don’t be late!

Four Or Two?

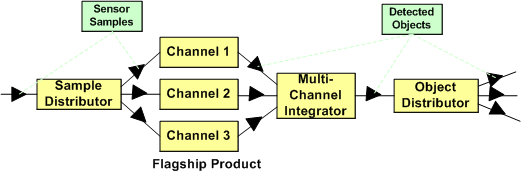

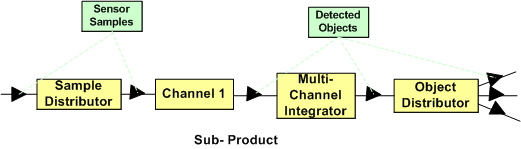

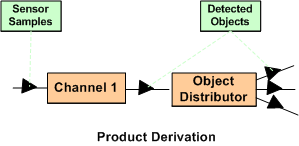

Assume that the figure below represents the software architecture within one of your flagship products. Also assume that each of the 6 software components are comprised of N non-trivial SLOC (Source Lines Of Code) so that the total size of the system is 6N SLOC. For the third assumption, pretend that a new, long term, adjacent market opens up for a “channel 1” subset of your product.

To address this new market’s need and increase your revenue without a ton of investment, you can choose to instantiate the new product from your flagship. As shown in the figure below, if you do that, you’ve reduced the complexity of your new product addition by 1/3 (6N to 4N SLOC) and hence, decreased the ongoing maintenance cost by at least that much (since maintainability is a non-linear function of software size).

Nevertheless, your new product offering has two unneeded software components in its design: the “Sample Distributor” and the “Multi-Channel Integrator”. Thus, if as the diagram below shows, you decide to cut out the remaining fat (the most reliable part in a system is the one that’s not there – because it’s not needed), you’ll deflate your long term software maintenance costs even further. Your new product portfolio addition would be 1/3 the original size (6N to 2N SLOC) of your flagship product.

If you had the authority, which approach would you allocate your resources to? Would you leave it to chance? Is the answer a no brainer, or not? What factors would prevent you from choosing the simpler two component solution over the four component solution? What architecture would your new customers prefer? What would your competitors do?

Sum Ting Wong

- SYS = Systems

- SW = Software

- HW = Hardware

When the majority of SYS engineers in an org are constantly asking the HW and SW engineers how the product works, my Chinese friend would say “sum ting (is) wong”. Since they’re the “domain experts”, the SYS engineers supposedly designed and recorded the product blueprints before the box was built. They also supposedly verified that what was built is what was specified. To be fair, if no useful blueprints exist, then 2nd generation SYS engineers who are assigned by org corpocrats to maintain the product can’t be blamed for not understanding how the product works. These poor dudes have to deal with the inherited mess left behind by the sloppy and undisciplined first generation of geniuses who’ve moved on to cushy “staff” and “management” positions.

Leadership is exploring new ground while leaving trail markers for those who follow. Failing to demand that first generation product engineers leave breadcrumbs on the trail is a massive failure of leadership.

If the SYS engineers don’t know how the product works at the “white box” level of detail, then they won’t be able to efficiently solve system performance problems, or conceive of and propose continuous improvements. The net effect is that the mysterious “black box” product owns them instead of vice versa. Like an unloved child, a neglected product is perpetually unruly. It becomes a serial misbehaver and a constant source of problems for its parents; leaving them confounded and confused when problems manifest in the field.

A corpocracry with leaders that are so disconnected from the day-to-day work in the bowels of the boiler room that they don’t demand system engineering ownership of products, get what they deserve; crappy products and deteriorating financial performance.