Archive

D4P4D

I just received two copies of William Livingston’s “Design For Prevention For Dummies” (D4P4D) gratis from the author himself. It’s actually section 7 of the “Non-Dummies” version of the book. With the addition of “For Dummies” to the title, I think it was written explicitly for me. D’oh!

The D4P is a mind bending, control theory based methodology (think feedback loops) for problem prevention in the midst of powerful, natural institutional forces that depend on problem manifestation and continued presence in order to keep the institution alive.

Mr. Livingston is an elegant, Shakespearian-type writer who’s fun to read but tough as hell to understand. I’ve enjoyed consuming his work for over 25 years but I still can’t understand or apply much of what he says – if anything!

As I slowly plod through the richly dense tome, I’ll try to write more posts that disclose the details of the D4P process. If you don’t see anything more about the D4P from me in the future, then you can assume that I’ve drowned in an ocean of confusion.

Human And Automated Controllers

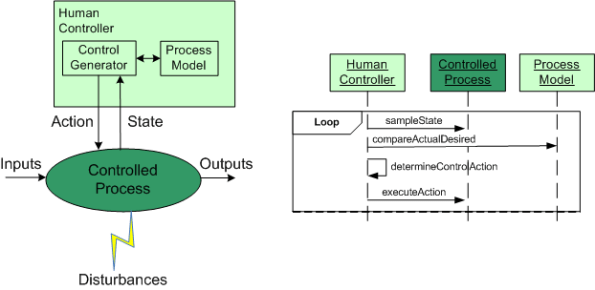

Note: The figures that follow were adapted from Nancy Leveson‘s “Engineering A Safer World“.

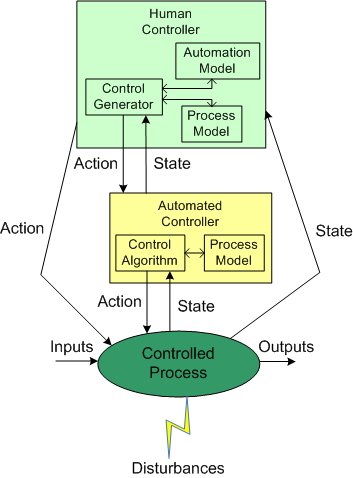

In the good ole days, before the integration of fast (but dumbass) computers into controlled-process systems, humans had no choice but to exercise direct control over processes that produced some kind of needed/wanted results. During operation, one or more human controllers would keep the “controlled process” on track via the following monitor-decide-execute cycle:

- monitor the values of key state variables (via gauges, meters, speakers, etc)

- decide what actions, if any, to take to maintain the system in a productive state

- execute those actions (open/close valves, turn cranks, press buttons, flip switches, etc)

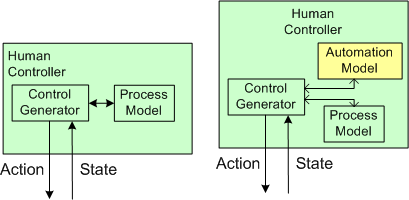

As the figure below shows, in order to generate effective control actions, the human controller had to maintain an understanding of the process goals and operation in a mental model stored in his/her head.

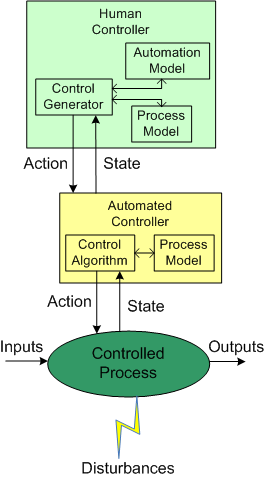

With the advent of computers, the complexity of systems that could be, were, and continue to be built has skyrocketed. Because of the rise in the cognitive burden imposed on humans to effectively control these newfangled systems, computers were inserted into the control loop to: (supposedly) reduce cognitive demands on the human controller, increase the speed of taking action, and reduce errors in control judgment.

The figure below shows the insertion of a computer into the control loop. Notice that the human is now one step removed from the value producing process.

Also note that the human overseer must now cognitively maintain two mental models of operation in his/her head: one for the physical process and one for the (supposedly) subservient automated controller:

Assuming that the automated controller unburdens the human controller from many mundane and high speed monitoring/control functions, then the reduction in overall complexity of the human’s mental process model may more than offset the addition of the requirement to maintain and understand the second mental model of how the automated controller works.

Since computers are nothing more than fast idiots with fixed control algorithms designed by fallible human experts (who nonetheless often think they’re infallible in their domain), they can’t issue effective control actions in disturbance situations that were unforeseen during design. Also, due to design flaws in the hardware or software, automated controllers may present an inaccurate picture of the process state, or fail outright while the controlled process keeps merrily chugging along producing results.

To compensate for these potentially dangerous shortfalls, the safest system designs provide backup state monitoring sensors and control actuators that give the human controller the option to override the “fast idiot“. The human controller relies primarily on the interface provided by the computer for monitoring/control, and secondarily on the direct interface couplings to the process.

B and S == BS

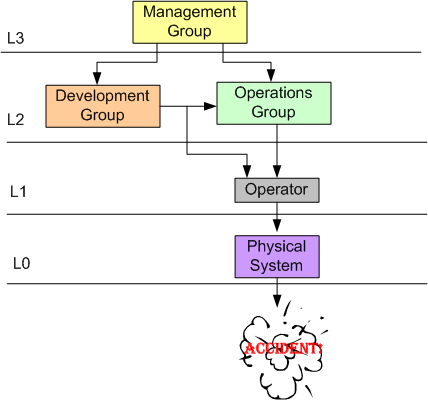

About a year ago, after a recommendation from management guru Tom Peters, I read Sidney Dekker’s “Just Culture“. I mention this because Nancy Leveson dedicates a chapter to the concept of a “just culture” in her upcoming book “Engineering A Safer World“.

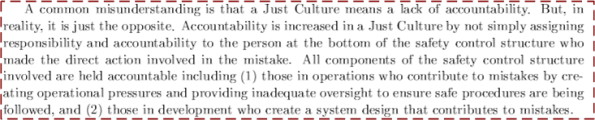

The figure below shows a simple view of the elements and relationships in an example 4 level “safety control structure“. In unjust cultures, when a costly accident occurs, the actions of the low elements on the totem pole, the operator(s) and the physical system, are analyzed to death and the “causes” of the accident are determined.

After the accident investigation is “done“, the following sequence of actions usually occurs:

- Blame and Shame (BS!) are showered upon the operator(s).

- Recommendations for “change” are made to operator training, operational procedures, and the physical system design.

- Business goes back to usual

- Rinse and repeat

Note that the level 2 and level 3 elements usually go uninvestigated – even though they are integral, influential forces that affect system operation. So, why do you think that is? Could it be that when an accident occurs, the level 2 and/or level 3 participants have the power to, and do, assume the role of investigator? Could it be that the level 2 and/or level 3 participants, when they don’t/can’t assume the role of investigator, become the “sugar daddies” to a hired band of independent, external investigators?

The Law Of Diminishing Returns…

Is It Safe?

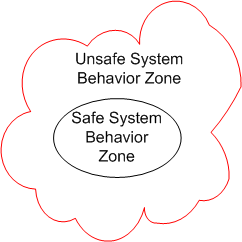

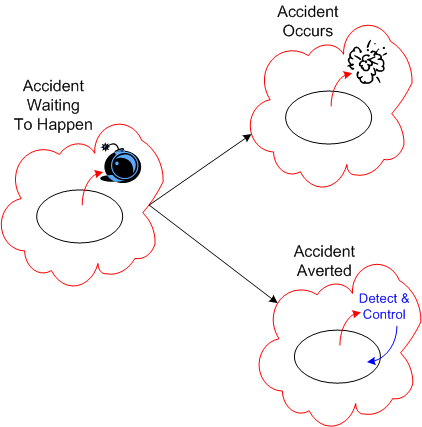

Assume that we place a large, socio-technical system designed to perform some safety-critical mission into operation. During the performance of its mission, the system’s behavior at any point in time (which emerges from the interactions between its people and machines), can be partitioned into 2 zones: safe and unsafe.

Since the second law of dynamics, like all natural laws, is impersonal and unapologetic, the system’s behavior will eventually drift into the unsafe system behavior zone over time. Combine the effects of the second law with poor stewardship on behalf of the system’s owner(s)/designer(s), and the frequency of trips into scary-land will increase.

Just because the system’s behavior veers off into the unsafe behavior zone doesn’t guarantee that an “unacceptable” accident will occur. If mechanisms to detect and correct unsafe behaviors are baked into the system design at the outset, the risk of an accident occurring can be lowered substantially.

Alas, “safety“, like all the other important, non-functional attributes of a system, is often neglected during system design. It’s unglamorous, it costs money, it adds design/development/test time to the sacred schedule. and the people who “do safety” are under-respected. The irony here is that after-the-accident, bolt-on, safety detection and control kludges cost more and are less trustworthy than doing it right in the first place.

Dysfunctional Interactions

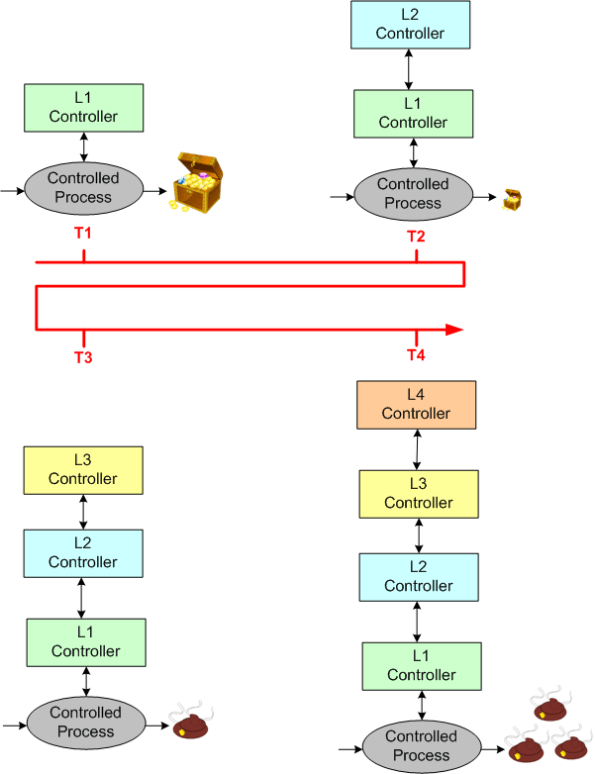

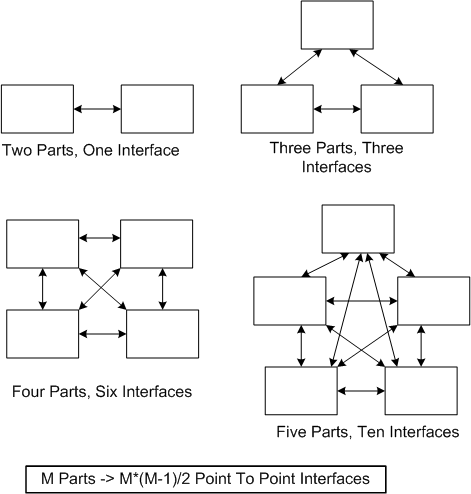

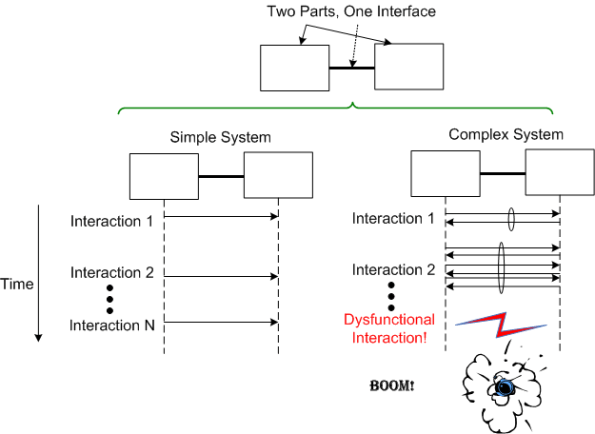

In “Engineering A Safer World“, Nancy Leveson states that dysfunctional interactions between system parts play a bigger role in accidents than individual part failures. Relative to yesterday’s systems, today’s systems contain many more parts. But because of manufacturing advances, each part is much more reliable than it used to be.

A consequence of adding more parts to a system is that the numbers of potential connections and interactions between parts starts exploding fast. Hence, there’s a greater chance of one dysfunctional interaction crashing the whole system – even whilst the individual parts and communication links continue to operate reliably.

Even with a “simple” two part system, if its designed-in purpose requires many rich and interdependent interactions to be performed over the single interface, watch out. A single dysfunctional interaction can cause the system to seize up and stop producing the emergent behavior it was designed to provide:

So, what’s the lesson here for system designers? It’s two-fold. Minimize the number of interfaces in your design and, more importantly, limit the number, types, and exchanges over each interface to only those that are required to fulfill the system’s purpose. Of course, if no one knows what’s required (which is the number one cause of unsuccessful systems), then you’re hosed no matter what. D’oh!

Out With The Old And In With The New

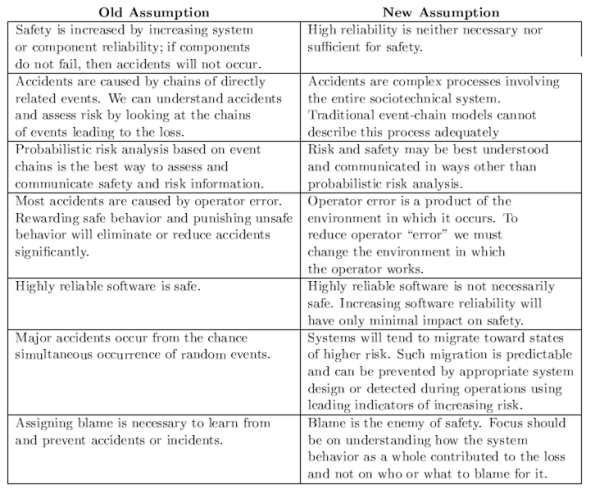

Nancy Leveson has a new book coming out that’s titled “Engineering A Safer World” (the full draft of the book is available here: EASW). In the beginning of the book, Ms. Leveson asserts that the conventional assumptions, theory, and techniques (FMEA == Failure Modes and Effects Analysis, Fault Tree Analysis == FTA, Probability Risk Assessment == PRA) for analyzing accidents and building safe systems are antiquated and obsolete.

The expert, old-guard mindset in the field of safety engineering is still stuck on the 20th century notion that systems are aggregations of relatively simple, electro-mechanical parts and interfaces. Hence, the steadfast fixation on FMEA, FTA, and PRA. On the contrary, most of the 21st century safety-critical systems are now designed as massive, distributed, software-intensive systems.

As a result of this emerging, brave new world, Ms. Leveson starts off her book by challenging the flat-earth assumptions of yesteryear:

Note that Ms. Leveson tears down the former truth of reliability == system_safety. After proposing her set of new assumptions, Ms. Leveson goes on to develop a new model, theory, and set of techniques for accident analysis and hazard prevention.

Note that Ms. Leveson tears down the former truth of reliability == system_safety. After proposing her set of new assumptions, Ms. Leveson goes on to develop a new model, theory, and set of techniques for accident analysis and hazard prevention.

Since the subject of safety-critical systems interests me greatly, I plan to write more about her novel approach as I continue to progress through the book. I hope you’ll join me on this new learning adventure.

Unavailability II

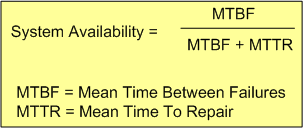

The availability of a software-intensive, electro-mechanical system can be expressed in equation form as:

With the complexity of modern day (and future) systems growing exponentially, calculating and measuring the MTBF of an aggregate of hardware and (especially) software components is virtually impossible.

Theoretically, the MTBF for an aggregate of hardware parts can be predicted if the MTBF of each individual part and how the parts are wired together, are “known“. However, the derivation becomes untenable as the number of parts skyrockets. On the software side, it’s patently impossible to predict, via mathematical derivation, the MTBF of each “part“. Who knows how many bugs are ready to rear their fugly heads during runtime?

From the availability equation, it can be seen that as MTTR goes to zero, system availability goes to 100%. Thus, minimizing the MTTR, which can be measured relatively easily compared to the MTBF ogre, is one effective strategy for increasing system availability.

The “Time To Repair” is simply equal to the “Time To Detect A Failure” + “The Time To Recover From The Failure“. But to detect a failure, some sort of “smart” monitoring device (with its own MTBF value) must be added to the system – increasing the system’s complexity further. By smart, I mean that it has to have built-in knowledge of what all the system-specific failure states are. It also has to continually sample system internals and externals in order to evaluate whether the system has entered one of those failures states. Lastly, upon detection of a failure, it has to either inform an external agent (like a human being) of the failure, or somehow automatically repair the failure itself by quickly switching in a “good” redundant part(s) for the failed part(s). Piece of cake, no?

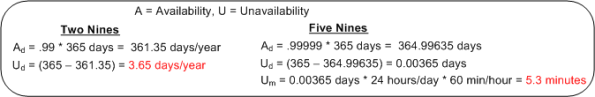

Unavailable For Business

The availability of a system is usually specified in terms of the “number of nines” it provides. For example, a system with an availability specification of 99.99 provides “two nines” of availability. As the figure below shows, a service that is required to provide five nines of availability can only be unavailable 5.3 minutes per year!

Like most of the “ilities” attributes, the availability of any non-trivial system composed of thousands of different hardware and software components is notoriously difficult and expensive to predict or verify before the system is placed into operation. Thus, systems are deployed and fingers crossed in the hope that the availability it provides meets the specification. D’oh!

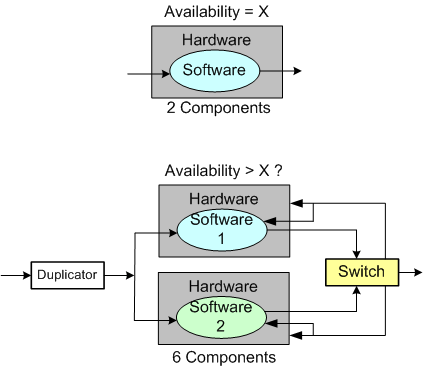

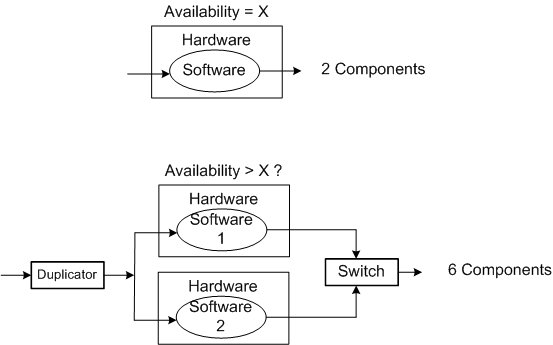

One way of supposedly increasing the availability of a system is to add redundancy to its design (see the figure below). But redundancy adds more complex parts and behavior to an already complex system. The hope is that the increase in the system’s unavailability and cost and development time caused by the addition of redundant components is offset by the overall availability of the system. Redundancy is expensive.

As you might surmise, the switch in the redundant system above must be “smart“. During operation, it must continuously monitor the health of both output channels and automatically switch outputs when it detects a failure in the currently active channel.

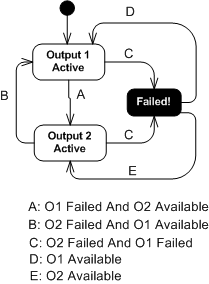

The state transition diagram below models the behavior required of the smart switch. When a switchover occurs due to a detected failure in the active channel, the system may become temporarily unavailable unless the redundant subsystem is operating as a hot standby (vs. cold standby where output is unavailable until it’s booted up from scratch). But operating the redundant channel as a hot standby stresses its parts and decreases overall system availability compared to the cold spare approach. D’oh!

Another big issue with adding redundancy to increase system availability is, of course, the BBoM software. If the BBoM running in the redundant channel is an exact copy of the active channel’s software and the failure is due to a software design or implementation defect (divide by zero, rogue memory reference, logical error, etc), that defect is present in both channels. Thus, when the switch dutifully does its job and switches over to the backup channel, it’s output may be hosed too. Double D’oh! To ameliorate the problem, a “software 2” component can be developed by an independent team to decrease the probability that the same defect is inserted at the same place. Talk about expensive?

Achieving availability goals is both expensive and difficult. As systems become more complex and human dependence on their services increases, designing, testing, and delivering highly available systems is becoming more and more important. As the demand for high availability continues to ooze into mainstream applications, those orgs that have a proven track record and deep expertise in delivering highly available systems will own a huge competitive advantage over those that don’t.

That’s All It Takes?

The MITRE corporation has a terrific web site loaded with information on the topic of system engineering. In spite of this, on the “Evolution of Systems Engineering” page, the conditions for system engineering success are laid out as:

- The system requirements are relatively well-established.

- Technologies are mature.

- There is a single or relatively homogeneous user community for whom the system is being developed.

- A single individual has management and funding authority over the program.

- A strong government program office capable of a peer relationship with the contractor.

- Effective architecting, including problem definition, evaluation of alternative solutions, and analysis of execution feasibility.

- Careful attention to program management and systems engineering foundational elements.

- Selection of an experienced, capable contractor.

- Effective performance-based contracting.

That’s it? That’s all it takes? Piece of cake. Uh, I think I’ll ship some parkas and igloo blueprints to hell to help those lost souls adapt to their new environment.