Archive

LSD… Far Out Man

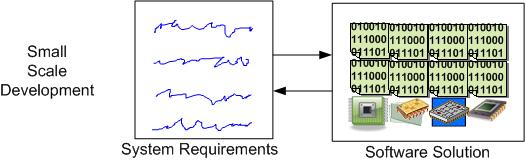

Alright, before we go on, let’s first get something out of the way so that we can start from the same context. This post is not about Small Scale Development (SSD) projects. As the following figure shows, on SDD projects one can successfully write code directly from a list of requirements (with some iterative back-and-forth of course) or set of use cases or (hopefully not) both.

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s talk about the real subject of this post: Large Scale Development (LSD <- appropriate acronym, no?) projects. On hallucinogenic LSD efforts, one or possibly two additional activities are required to secure any chance at timely success. As the next figure shows, these two activities are “System Design” and “Software Design“.

So, what’s the difference between “system design” and “software design“? Well, if you’re developing software-intensive products for a specialized business domain (e.g. avionics, radar, sonar, medical, taxes), then you’re gonna need domain experts to bridge the GOHI (Gulf Of Human Intellect) between the higher level requirements and the lower level software design…..

Most specialized domain experts don’t know enough about general software design (object-oriented, structured, functional) and most software experts don’t know enough about domain-specific design to allow for successfully skipping the system design phase/stage. But that hasn’t stopped orgs from doing this….

Most specialized domain experts don’t know enough about general software design (object-oriented, structured, functional) and most software experts don’t know enough about domain-specific design to allow for successfully skipping the system design phase/stage. But that hasn’t stopped orgs from doing this….

Motorcycle And Software Maintenance

Robert Pirsig’s “Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance” is one of my fave books of all time. I have a soft cover copy that I bought in the nineties. Because of its infinite depth and immersive pull, I’ve read it at least three times over the years. Thus, when Amazon.com sent me a recommendation for the kindle version of it for $2.99, I jumped at the chance to e-read it and capture some personally meaningful notes from it.

(Published in 1974) the book sold 5 million copies worldwide. It was originally rejected by 121 publishers, more than any other bestselling book, according to the Guinness Book of Records. – Wikipedia

In a nutshell, ZATAOMM is about a college professor (Pirsig himself) who ends up going insane over his obsession with trying to objectively define what the metaphysical concept of “quality” means.

Quality…you know what it is, yet you don’t know what it is. But that’s self-contradictory. But some things are better than others, that is, they have more quality. But when you try to say what the quality is, apart from the things that have it, it all goes poof! There’s nothing to talk about. But if you can’t say what Quality is, how do you know what it is, or how do you know that it even exists? If no one knows what it is, then for all practical purposes it doesn’t exist at all.

During my fourth read of ZATAOMM, I started noticing how much of the wisdom Mr. Pirsig proffers up applies to the “art” of software development/maintenance:

When you want to hurry something, that means you no longer care about it and want to get on to other things.

This comes up all the time in

mechanicalsoftware work. A hang-up. You just sit and stare and think, and search randomly for new information, and go away and come back again, and after a while the unseen factors start to emerge.Sometimes just the act of writing down the problems straightens out your head as to what they really are.

The craftsman isn’t ever following a single line of instruction. He’s making decisions as he goes along. For that reason he’ll be absorbed and attentive to what he’s doing even though he doesn’t deliberately contrive this. He isn’t following any set of written instructions because the nature of the material at hand determines his thoughts and motions, which simultaneously change the nature of the material at hand.

Any effort that has self-glorification as its final endpoint is bound to end in disaster.

Stuck. No answer. Honked. Kaput. It’s a miserable experience emotionally. You’re losing time. You’re incompetent. You don’t know what you’re doing. You should be ashamed of yourself.

This gumption trap of anxiety, which results from overmotivation, can lead to all kinds of errors of excessive fussiness. You fix things that don’t need fixing, and chase after imaginary ailments. You jump to wild conclusions and build all kinds of errors into the machine because of your own nervousness.

Impatience is close to boredom but always results from one cause: an underestimation of the amount of time the job will take. You never really know what will come up and very few jobs get done as quickly as planned. Impatience is the first reaction against a setback and can soon turn to anger if you’re not careful.

Impatience, stuckness, underestimation, anxiety, and carelessness. These are just a subset of the feelings and behaviors that pervade dysfunctionally soulless organizations whose sole focus is on “following prescribed process and meeting schedule“.

Hand In Hand

Me thinks that these two quotes go together hand in hand, and in the order presented:

“At first I hoped that such a technically unsound project would collapse but I soon realized it was doomed to success.” – C. A. Hoare

“The bitterness of poor system performance remains long after the sweetness of low prices and prompt delivery are forgotten.” – Jerry Lim

Have you ever participated on a project that made it out the door but caused financial and social “problems” sometime downstream? Lucky for him, BD00 hasn’t.

What’s The Diff?

One of the problems I’ve always had with the word “agile” is that it’s so overloaded (like “system“) that anyone can claim “agility“:

Everyone is doing agile these days – even those who aren’t – Scott Ambler

Along this vein, check out this slide from a unnamed agile expert:

Now tell me, how is this advice different from the unconscionable and anti-agile:

To define tests, you have to have some understanding of the requirements to test against in your cranium, no? It’s just that, in agile-land, you’ll be excommunicated from the cult if you formally write them down before slinging code. WTF?

Like “agile” was a backlash against “waterfall” in the past, maybe “waterfall” will be a circular backlash against “agile” in the future?

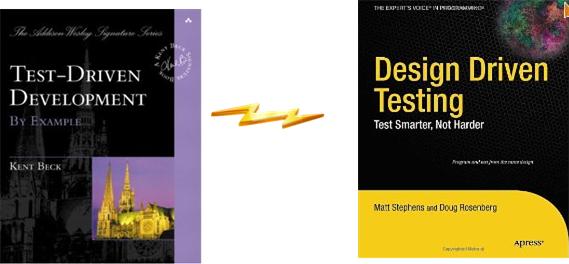

Likewise, instead of creating an emergent Frankensteinian design with revered “TDD“, why not hop off the bandwagon and create emergent tests with “DDT“?

Asynchronous Flows And Synchronous Transactions

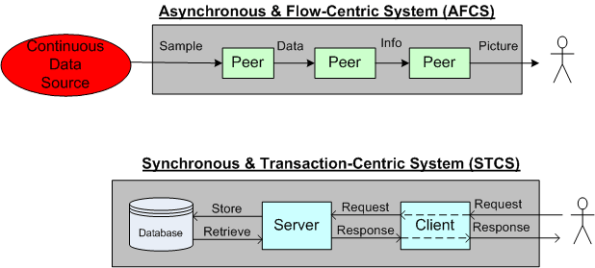

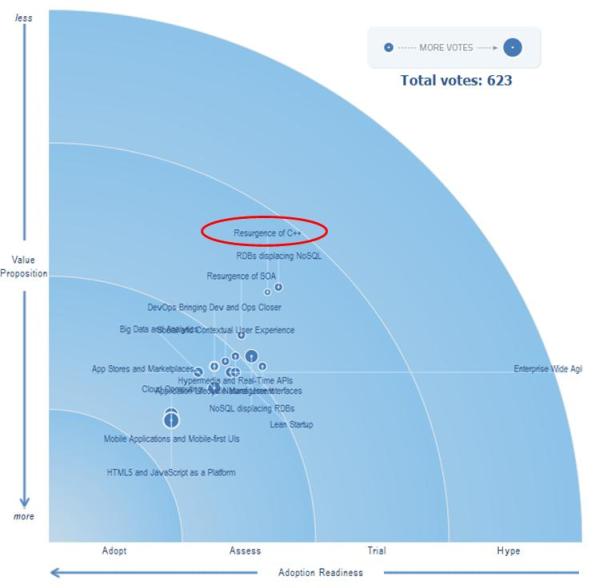

The figure below shows a pair of BD00 concocted models for two classes of systems; peer-to-peer and client-server:

The primary mission of an AFCS is to progressively transform a high rate stream of incoming raw samples into a higher level, abstract representation of some phenomena that’s important to its users. In an STCS, the system’s primary mission is to transform low rate user requests into information that’s important to its users.

In business support applications, STC systems dominate the scene. In aerospace and defense applications, AFC systems are king. Of course, the situation is never as simplistic as BD00 sez. Hybrid systems like the sensor-based command and control model below can be found everywhere.

For some reason (maybe market size and/or community culture and/or media exposure?), most software technology advancements (languages, patterns, methodologies, frameworks, etc) seem to emerge out of the STCS space. Those innovations that are “applicable” get adopted in the AFCS space. Hell, even those that are inapplicable (because they weren’t designed with performance as the top priority) get adopted.

Hyped And Valueless

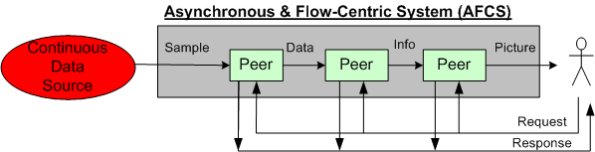

In “Major Software Development Trends for 2013”, the editors of InfoQ asked its readers to rank several software development trends in terms of their “adoption readiness” and the “value proposition” they offer. As you can see below, the 623 voters (so far) think that “the resurgence of C++” is the least valuable and least adoptable among the 16 listed trends.

My take, and I fully admit to being totally biased for C++11, is that the vast majority of voters are web, mobile, or IT business application developers. They don’t develop real-time and/or safety-critical systems where C and C++ excel. Hell, just looking at the list of trends, you can tell that they are all geared toward web/mobile/IT applications. But that makes sense because the market for those types of apps dwarfs all others and that’s what’s driving the relentless innovation that keeps the software industry fresh, new, and brutally exciting.

Boulders And Pebbles

When embarking on a Software Product Line (SPL) development, one of the first, far-reaching cost decisions to be tackled is the level of “granularity” of the component set. Obviously, you don’t want to develop one big, fat-ass, 5 million line monstrosity that has to have 1000s of lines changed/added/hacked for each customer “instantiation“. Gee, that’s probably how you operate now and why you’re tinkering with the idea of an SPL approach for the future.

On the other hand, you don’t want to build 1000s of 10K-line pieces that are a nightmare for composition, configuration, versioning and integration. For a given domain, there’s a “subjective” sweet spot somewhere between a behemoth 5M-line boulder and a basket of 10K-line pebbles. However, if you’re gonna err on one side or the other, err on the side of “bigger“:

…beware of overly fine-grained components, because too many components are hard to manage, especially when versioning rears its ugly head, hence “DLL hell.” – Martin Fowler (UML Distilled)

The primacy of system functions and system function groups allows a new member of the product line to be treated as the composition of a few dozen high-quality, high-confidence components that interact with each other in controlled, predictable ways as opposed to thousands of small units that must be regression tested with each new change. Assembly of large components without the need to retest at the lowest level of granularity for each new system is a critical key to making reuse work. – Brownsword/Clements (A Case Study In Successful Product Line Development)

We Must!

Time For A Toga Party!

So, How Do You Know?

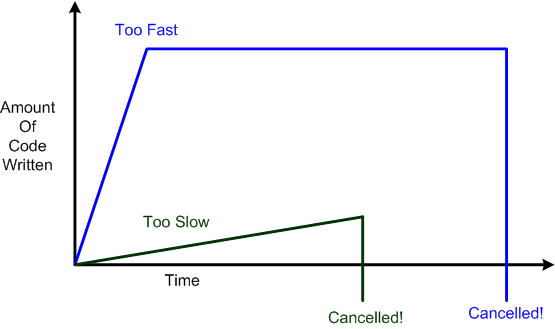

In the software development industry, going too slow can result in nothing getting done in an “acceptable” amount of time and thus, impatient managers cancelling projects. On the other hand, going too fast can result in hackneyed designs, halted downstream progress due to lots of rework on an unmanageable code base, and thus, frustrated managers cancelling projects.

As the figure below shows, the irony is that going too slow can result in less sunk cost due to earlier cancellation than going too fast – which gives a false illusion of great progress till the fit hits the shan.

So, how do you “objectively” know if you’re going too fast or too slow? It’s simple: you freakin’ don’t. However, in a world increasingly dominated by “agile” indoctrination, faster seems to be always equated with better and the tortoise vs. hare parable is heresy.