Archive

Going Turbo-Agile

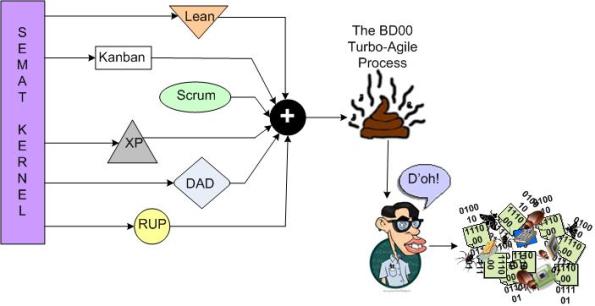

I’m planning on using the state of the art SEMAT kernel to cherry-pick a few “best practices” and concoct a new, proprietary, turbo-agile software development process. The BD00 Inc. profit deluge will come from teaching 1 hour certification courses all over the world for $2000 a pop. To fund the endeavor, I’m gonna launch a Kickstarter project.

What do you think of my slam dunk plan? See any holes in it?

Alternative Considerations

Before you unquestioningly accept the gospel of the “evolutionary architecture” and “emergent design” priesthood, please at least pause to consider these admonitions:

Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe – Abe Lincoln

Measure twice, cut once – Unknown

If I had an hour to save the world, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute finding solutions – Albert Einstein

100% test coverage is insufficient. 35% of the faults are missing logic paths – Robert Glass

Rule-Based Safety

In this interesting 2006 slide deck, “C++ in safety-critical applications: the JSF++ coding standard“, Bjarne Stroustrup and Kevin Carroll provide the rationale for selecting C++ as the programming language for the JSF (Joint Strike Fighter) jet project:

First, on the language selection:

- “Did not want to translate OO design into language that does not support OO capabilities“.

- “Prospective engineers expressed very little interest in Ada. Ada tool chains were in decline.“

- “C++ satisfied language selection criteria as well as staffing concerns.“

They also articulated the design philosophy behind the set of rules as:

- “Provide “safer” alternatives to known “unsafe” facilities.”

- “Craft rule-set to specifically address undefined behavior.”

- “Ban features with behaviors that are not 100% predictable (from a performance perspective).”

Note that because of the last bullet, post-initialization dynamic memory allocation (using new/delete) and exception handling (using throw/try/catch) were verboten.

Interestingly, Bjarne and Kevin also flipped the coin and exposed the weaknesses of language subsetting:

What they didn’t discuss in the slide deck was whether the strengths of imposing a large coding standard on a development team outweigh the nasty weaknesses above. I suspect it was because the decision to impose a coding standard was already a done deal.

Much as we don’t want to admit it, it all comes down to economics. How much is the lowering of the risk of loss of life worth? No rule set can ever guarantee 100% safety. Like trying to move from 8 nines of availability to 9 nines, the financial and schedule costs in trying to achieve a Utopian “certainty” of safety start exploding exponentially. To add insult to injury, there is always tremendous business pressure to deliver ASAP and, thus, unconsciously cut corners like jettisoning corner-case system-level testing and fixing hundreds of “annoying” rules violations.

Does anyone have any data on whether imposing a strict coding standard actually increases the safety of a system? Better yet, is there any data that indicates imposing a standard actually decreases the safety of a system? I doubt that either of these questions can be answered with any unbiased data. We’ll just continue on auto-believing that the answer to the first question is yes because it’s supposed to be self-evident.

Revolution, Or Malarkey?

BD00 has been following the development of Ivar Jacobson et al’s SEMAT (Software Engineering Method And Theory) work for a while now. He hasn’t decided whether it’s a revolutionary way of thinking about software development or a bunch of pseudo-academic malarkey designed to add funds to the pecuniary coffers of its creators (like the late Watts Humphrey’s, SEI-backed, PSP/TSP?).

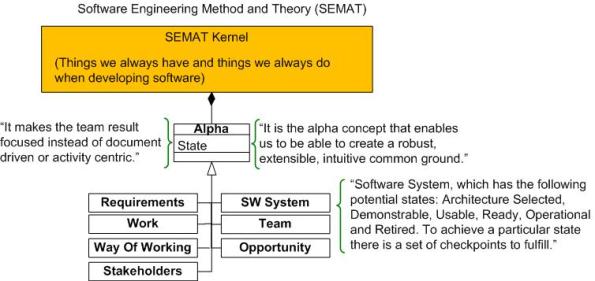

To give you (and BD00!) an introductory understanding of SEMAT basics, he’s decided to write about it in this post. The description that follows is an extracted interpretation of SEMAT from Scott Ambler‘s interview of Ivar: “The Essence of Software Engineering: An Interview with Ivar Jacobson”.

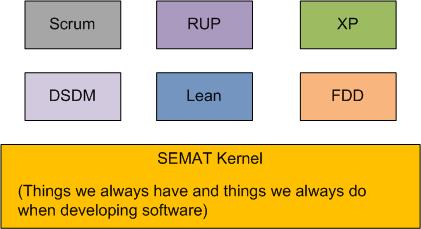

As the figure below shows, the “kernel” is the key concept upon which SEMAT is founded (note that all the boasts, uh, BD00 means, sentences, in the graphic are from Ivar himself).

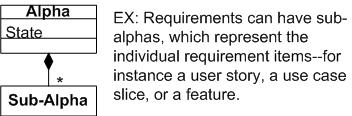

In its current incarnation, the SEMAT kernel is comprised of seven, fundamental, widely agreed-on “alphas“. Each alpha has a measurable “state” (determined by checklist) at any time during a development endeavor.

At the next lower level of detail, SEMAT alphas are decomposed into stateful sub-alphas as necessary:

As the diagram below attempts to illustrate, the SEMAT kernel and its seven alphas were derived from the common methods available within many existing methodologies (only a few representative methods are shown).

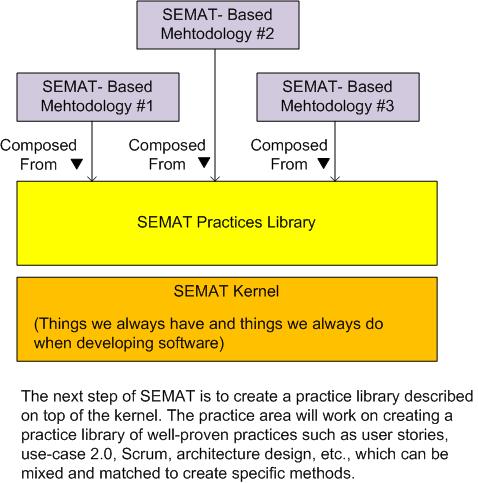

In the eyes of a SEMATian, the vision for the future of software development is that customized methods will be derived from the standardized (via the OMG!) kernel’s alphas, sub-alphas, and a library of modular “practices“. Everyone will evolve to speak the SEMAT lingo and everything will be peachy keen: we’ll get more high quality software developed on time and under budget.

OK, now that he’s done writing about it, BD00 has made an initial assessment of the SEMAT: it is a bunch of well-intended malarkey that smacks of Utopian PSP/TSP bravado. SEMAT has some good ideas and it may enjoy a temporary rise in popularity, but it will fall out of favor when the next big silver bullet surfaces – because it won’t deliver what it promises on a grand scale. Of course, like other methodology proponents, SEMAT’s advocates will tout its successes and remain silent about its failures. “If you’re not succeeding, then you’re doing it wrong and you need to hire me/us to help you out.”

But wait! BD00 has been wrong so many times before that he can’t remember the last time he was right. So, do your own research, form an opinion, and please report it back here. What do you think the future holds for SEMAT?

Uncomfortable With Ambiguity

Uncertain: Not able to be relied on; not known or definite

Ambiguous: Open to more than one interpretation; having a double meaning.

Every spiritual book I’ve ever read advises its readers to learn to become comfortable with “uncertainty” because “uncertainty is all there is“. BD00 agrees with this sage advice because fighting with reality is not good for the psyche.

Ambiguity, on the other hand, is a related but different animal. It’s not open-ended like its uncertainty parent. Ambiguity is the next step down from uncertainty and it consists of a finite number of choices; one of which is usually the best choice in a given context. The perplexing dilemma is that the best choice in one context may be the worst choice in a different context. D’oh!

Many smart people that I admire say things like “learn to be comfortable with ambiguity“, but BD00 is not onboard with that approach. He’s not comfortable with ambiguity. Whenever he encounters it in his work or (especially) in the work of others that his work depends on for progressing forward, he doggedly tries to resolve it – with whatever means available.

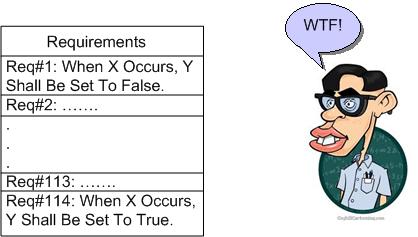

The main reason behind BD00’s antagonistic stance toward ambiguity is that ambiguity doesn’t compile – but the code must compile for progress to occur. Thus, if ambiguity isn’t consciously resolved between the ambiguity creator (ambiguator) and the ambiguity implementer (ambiguatee) before slinging code, it will be unconsciously resolved somehow. To avoid friction and perhaps confrontation between ambiguator and ambiguatee (because of differences in stature on the totem pole?), an arbitrary and “undisclosed” decision will be made by the implementer to get the code to compile and progress to occur- most likely leading to functionally incorrect code and painful downstream debugging.

So, BD00’s stance is to be comfortable with uncertainty but uncomfortable with ambiguity. Whenever you encounter the ambiguity beast, consciously attack it with a vengeance and publicly resolve it ASAP with all applicable stakeholders.

Which Path?

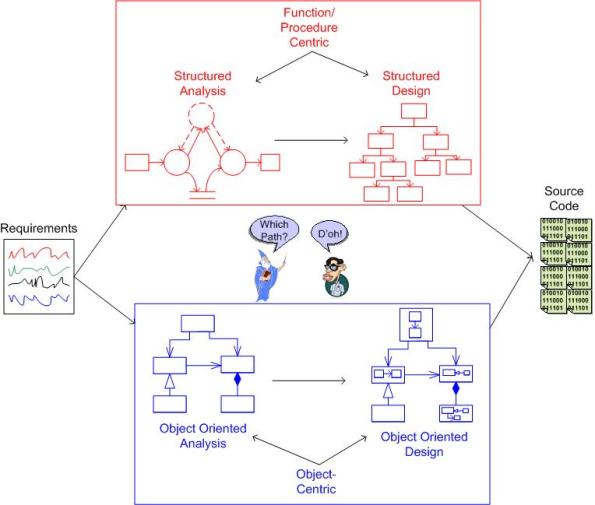

Please peruse the graphic below and then answer these questions for BD00: Is it a forgone conclusion that object-oriented development is the higher quality path from requirements to source code for all software-intensive applications? Has object-oriented development transitioned over time from a heresy into a dogma?

With the rising demand for more scaleable, distributed, fault-tolerant, concurrent systems and the continuing maturation of functional languages (founded on immutability, statelessness, message-passing (e.g. Erlang, Scala)), choosing between object-oriented and function-oriented technical approaches may be more important for success than choosing between agile development methodologies.

Intimately Bound

Out of the bazillions of definitions of “software architecture” out in the wild, my favorite is:

“the initial set of decisions that are costly to change downstream“.

It’s my fave because it encompasses the “whole” product development ecosystem and not just the structure and behavior of the product itself. Here are some example decisions that come to mind:

- Programming language(s)

- Third party libraries

- Architectural pattern/style

- Build system selection

- Targeted operating system(s)

- Version control system

- Automated testing framework

- Communication middleware

- GUI framework

- Requirements management tool

- Non-functional requirements (latency, throughput, availability, security, safety)

- Development process

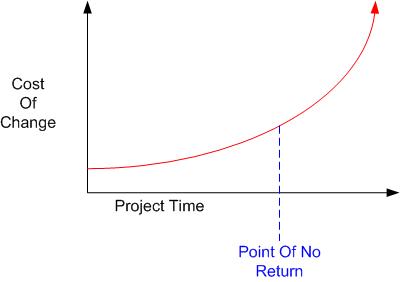

Once your production code gets intimately bound with the set of items on the list, there comes a point of no return on the project timeline where changing any of them is pragmatically impossible. Once this mysterious time threshold is crossed, changing the product source code may be easier than changing anything else on the list.

Got any other items to add to the list?

A Blast From The Past

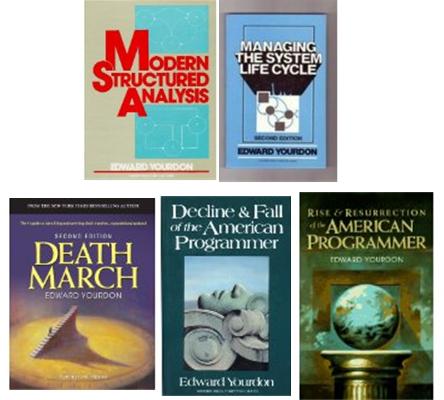

In the 1980s, Ed Yourdon was very visible and influential in the software development industry. Arguably, Ed was the equivalent to what Martin Fowler is today – a high profile technical guru. Then at some point, it seemed like Mr. Yourdon disappeared off the face of the earth. He really didn’t vanish, but he’s much less visible now than he was back then. He’s actually making big bux serving as an expert witness in software disaster court cases.

Since I enjoyed Ed’s work on structured systems analysis/design (before the OO juggernaut took off) and I’ve read several of his articles and books over the years, I was delighted to discover this InfoQ interview: “Ed Yourdon on the State of Agile and Trends in IT“.

In the interview, Ed states that he’s asked many CIOs what “agile” means to them. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of them said that it enabled developers to write software faster. Of course, there was no mention of the higher quality and/or the elevated espirit de corps that’s “supposed” to hitch a free ride on the agile gravy train.

Working Code Over Comprehensive Documentation

Comprehensiveness is the enemy of comprehensibility – Martin Fowler

Martin’s quote may be the main reason why this preference was written into the Agile Manifesto…

Working software over comprehensive documentation

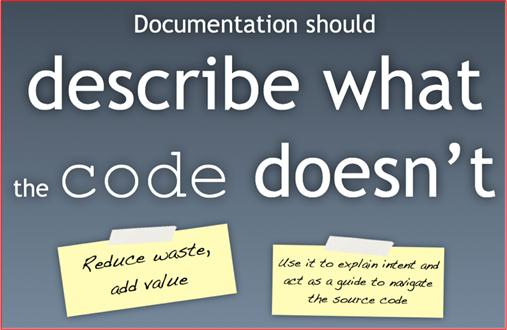

Obviously, it doesn’t say “Working software and no documentation“. I’d bet my house that Martin and his fellow colleagues who conjured up the manifesto intentionally stuck the word “comprehensive” in there for a reason. And the reason is that “good” documentation reduces costs in both the short and long runs. In addition, check out what the Grade-ster has to say:

The code tells the story, but not the whole story – Grady Booch

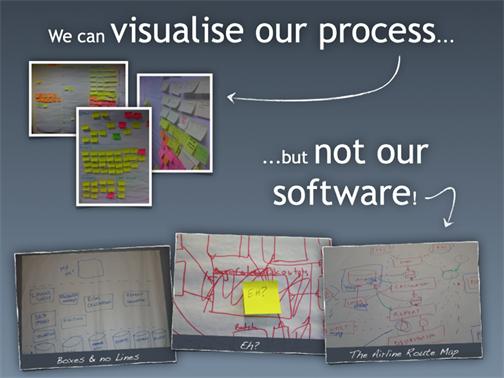

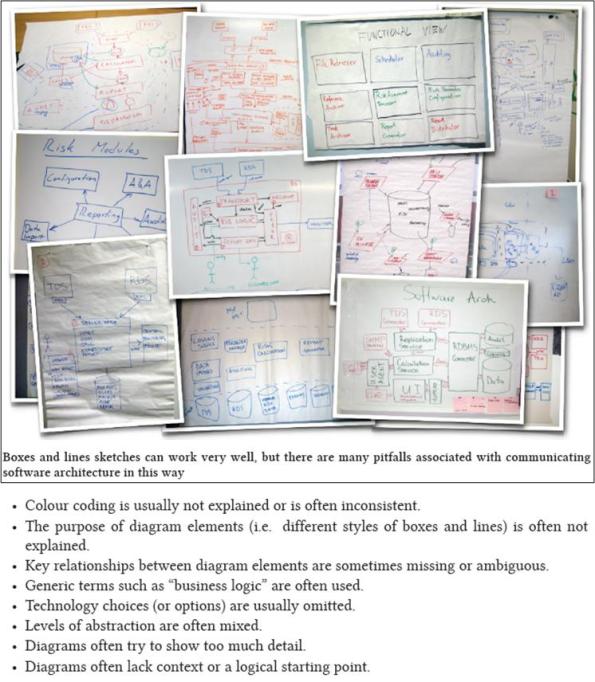

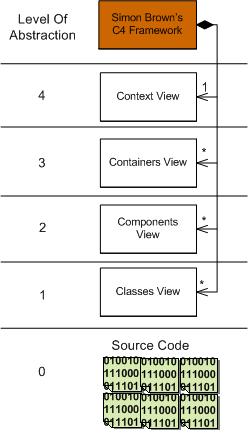

Now that the context for this post has been set, I’d like to put in a plug for Simon Brown’s terrific work on the subject of lightweight software architecture documentation. In tribute to Simon, I decided to hoist a few of his slides that resonate with me.

Note that the last graphic is my (and perhaps Simon’s?) way of promoting standardized UML-sketching for recording and communicating software architectures. Of course, if you don’t record and communicate your software architectures, then reading this post was a waste of your time; and I’m sorry for that.

How Can We Make This Simpler?

The biggest threat to success in software development is the Escalation of Unessential Complexity (EUC). Like stress is to humans, EUC is a silent project/product killer lurking in the shadows – ready to pounce. If your team isn’t constantly asking “how can we make this simpler?” as time ticks by and money gets burned, then your project and product will probably get hosed somewhere downstream.

But wait! It’s even worse than you think. Asking “how can we make this simpler?” applies to all levels and areas of a project: requirements, architecture, design, code, tools, and process. Simply applying continuous inquiry to one or two areas might delay armageddon, but you’ll still probably get hosed.

If you dwell in a culture that reveres or is ignorant of EUC, then you most likely won’t ever hear the question “how can we make this simpler?” getting asked.

But no need to fret. All ya gotta do to calm your mind is embrace this Gallism :

In complex systems, malfunction and even total malfunction may not be detectable for long periods, if ever – John Gall