Archive

Design Disaster

In an attempt to gain an understanding of the software design he was carrying around in his head, I sat down with a colleague and started talking face to face with him. To facilitate the conversation, I started sketching my emergent understanding of his design in my notebook. As you can see, by the time we finished talking, 20 minutes later, I ran out of ink and I wasn’t much better off than before we started the conversation:

If I had a five year old son, I would proudly magnetize my sketch on the fridge right next to his drawings.

The Angle Bracket Tax

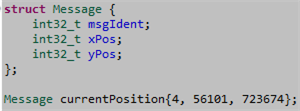

The following C++14 code fragment represents a general message layout along with a specific instantiation of that message:

Side note: Why won’t a C++98/03 compiler accept the above code?

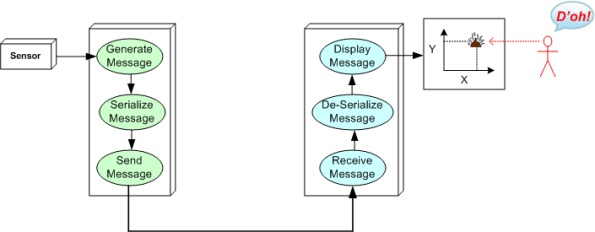

Assume that we are “required” to send thousands of these X-Y position messages per second between two computers over a finite bandwidth communication link:

There are many ways we can convert the representation of the message in memory into a serial stream of bytes for transmittal over the communication link, but let’s compare a simple binary representation against an XML equivalent:

The tradeoff is simple: human readability for performance. Even though the XML version is self-describing and readable to a human being, it is 6.5 times larger than the tight, fixed-size, binary format. In addition, the source code required to serialize/deserialize (i.e. marshal/unmarshal) the XML version is computationally denser than the code to implement the same functionality for the fixed-size, binary representation. In the software industry, this tradeoff is affectionately known as “the angle bracket tax” that must be payed for using XML in the critical paths of your system.

If your system requires high rates of throughput and low end-to-end latency for streaming data over a network, you may have no choice but to use a binary format to send/receive messages. After all, what good is it to have human readable messages if the system doesn’t work due to overflowing queues and lost messages?

The Meta-Documentation Dilemma

In his terrific “Effective architecture sketches” slide deck, Simon Brown rightly states that you don’t need UML to sketch up your software architecture. However, if you don’t, you need to consider documenting the documentation:

The utility of using a standard like UML is that you don’t have to spend any time on all the arcane subtleties of meta-documentation. And if you’re choosing to bypass the UML, you’re probably not going to spend much time, if any, doing meta-documentation to clarify your architecture decisions. After all, doing less documentation, let alone writing documentation about the documentation, is why you eschewed UML in the first place.

So, good luck in unambiguously communicating the software architecture to your stakeholders; especially those poor souls who will be trying to build the beast with you.

Myopia And Hyperopia

Assume that we’ve just finished designing, testing, and integrating the system below:

Now let’s zoom in on the “as-built“, four class, design of SS2 (SubSystem 2). Assume its physical source tree is laid out as follows:

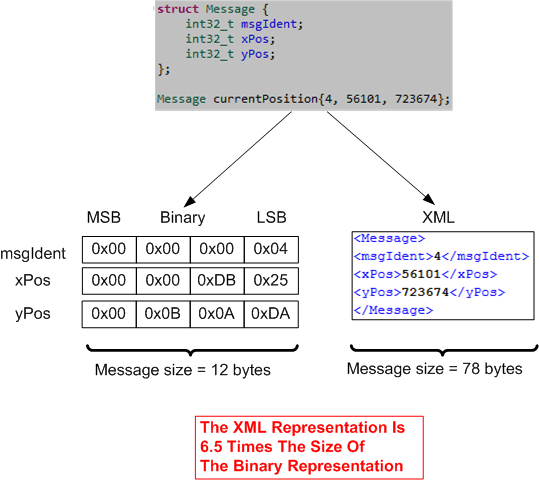

Given this design data after the fact, some questions may come to mind: How did the four class design cluster come into being? Did the design emerge first, the production code second, and the unit tests come third in a neat and orderly fashion? Did the tests come first and the design emerge second? Who gives a sh-t what the order and linearity of creation was, and perhaps more importantly, why would someone give a sh-t?

It seems that the TDD community thinks the way a design manifests is of supreme concern. You see, some hard core TDD zealots think that designing and writing the test code first ala a strict “red-green-refactor” personal process guarantees a “better” final design than any other way. And damn it, if you don’t do TDD, you’re a second class citizen.

BD00 thinks that as long as refactoring feedback loops exist between the designing-coding-testing efforts, it really doesn’t freakin’ matter which is the cart and which is the horse, nor even which comes first. TDD starts with a local, myopic view and iteratively moves upward towards global abstraction. DDT (Design Driven Test) starts with a global, hyperopic view and iteratively moves downward towards local implementation. A chaotic, hybrid, myopia-hyperopia approach starts anywhere and jumps back and forth as the developer sees fit. It’s all about the freedom to choose what’s best in the moment for you.

Notice that TDD says nothing about how the purely abstract, higher level, three-subsystem cluster (especially the inter-subsystem interfaces) that comprise the “finished” system should come into being. Perhaps the TDD community can (should?) concoct and mandate a new and hip personal process to cover software system level design?

Gilbitecture

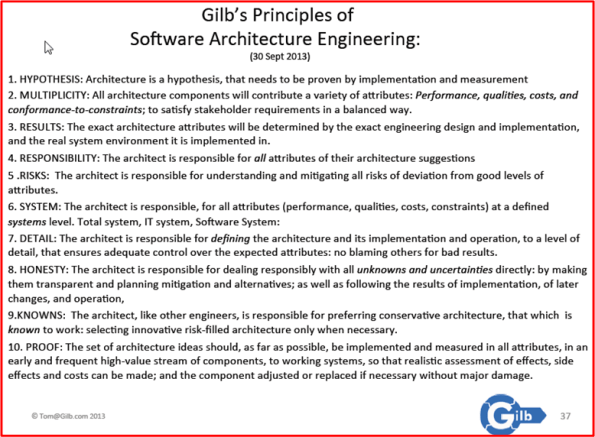

Plucked from his deliciously titled “Real Architecture: Engineering or Pompous Bullshit?” slide deck, I give you Tom Gilb‘s personal principles of software architecture engineering:

Tom’s proactive approach seems like a far cry from the reactive approaches of the “emergent architecture” and TDA (Test Driven Architecture) communities, doesn’t it?

OMG! Tom’s list actually uses the words “engineering” and “the architect“. Maybe that’s why I have always appreciated his work so much. 🙂

Regardless Of Agile Or Waterfall

The figure below depicts an architectural view of a real-time embedded sub-system that I and a team of 8 others built and delivered 10 (freakin!) years ago. At revision number 9, the diagram ended up being the final “as-built” model of the 20,000+ lines-of-code system. Since the software was written in C and, thus, not object-oriented, I chose not to use UML to capture the design at the time. Doing so would have introduced an impedance mismatch and a large intellectual gap of misunderstanding between the procedural C code base and the OO design artifacts. I used structured analysis and functional decomposition to concoct the design and I employed “pseudo” Data Flow Diagrams (DFD) instead.

At the beginning of this “waterfall” project, I created revision 0 of the diagram as the first “build-to” snapshot. Of course, as learning accrued and the system evolved throughout development, I diligently kept the diagram updated and synchronized with the code base in true PAYGO fashion.

As you can see from the picture, the system of 30+ asynchronous application tasks ran under the tutelage of the industrial-strength VxWorks Real Time Operating System (RTOS). Asynchronous inter-task communication was performed via message passing through a series of lock-protected queues. The embedded physical board was powered by a Motorola PowerPC CPU (remember those dinosaurs?). The board housed a myriad of serial and ethernet interface ports for communication to other external sub-systems.

The above diagram was not the sole artifact that I used to record the design. It was simply the highest level, catch-all, overview of the system. I also developed a complementary set of lower level functional diagrams; each of which captured a sliced view of an end-to-end strand of critical functionality. One of these diagrams, the “Uplink/Downlink Processing View“, is shown below. Note that the final “as-built” diagram settled out as revision number 5.

The purpose of this post was simply to give you a taste of how I typically design and evolve a non-trivial software-intensive system that I can’t entirely keep in my head. I use the same PAYGO process for all of my efforts regardless of whether the project is being managed as an agile or waterfall endeavor. To me, project process is way over-emphasized and overblown. “Business Value” creation ultimately distills down to architecture, design, coding, and testing at all levels of abstraction.

Where To Start?

The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise. — Edsger Dijkstra

With Edsger’s delicious quote in mind, let’s explore seven levels of abstraction that can be used to reason about big, distributed, systems:

At level zero, we have the finest grained, most concrete unit of design, a single puny line of “source code“. At level seven, we have the coarsest grained, most abstract unit of design, the mysterious and scary “system” level. A line of code is simple to reason about, but a “system” is not. Just when you think you understand what a system does, BAM! It exhibits some weird, perhaps dangerous, behavior that is counter-intuitive and totally unexpected – especially when humans are the key processing “nodes” in the beast.

Here are some questions to ponder regarding the seven level stack: Given that you’re hired to build a big, distributed system, at what level would you start your development effort? Would you start immediately coding up classes using the much revered TDD “best practice” and let all the upper levels of abstraction serendipitously “emerge”? Relatively speaking, how much time “up front” should you spend specifying, designing, recording, communicating the structures and behaviors of the top 3 levels of the stack? Again, relatively speaking, how much time should be allocated to the unit, integration, functional, and system levels of testing?

Let the Design Emerge, But Not The Architecture

I’m not a fan of “emergent global architecture“, but I AM a fan of “emergent local design“. To mitigate downstream technical and financial risk, I believe that one has to generate and formally document an architecture at a high level of abstraction before starting to write code. To do otherwise would be irresponsible.

The figure below shows a portion of an initial “local” design that I plucked out of a more “global” architectural design. When I started coding and unit testing the cluster of classes in the snippet, I “discovered” that the structure wasn’t going work out. The API of the architectural framework within which the class cluster runs wouldn’t allow it to work without some major, internal, restructuring and retesting of the framework itself.

After wrestling with the dilemma for a bit, the following workable local design emerged out of the learning acquired via several wretched attempts to make the original design work. Of course, I had to throw away a bunch of previously written skeletal product and test code, but that’s life. Now I’m back on track and moving forward again. W00t!

Not So Nice And Tidy

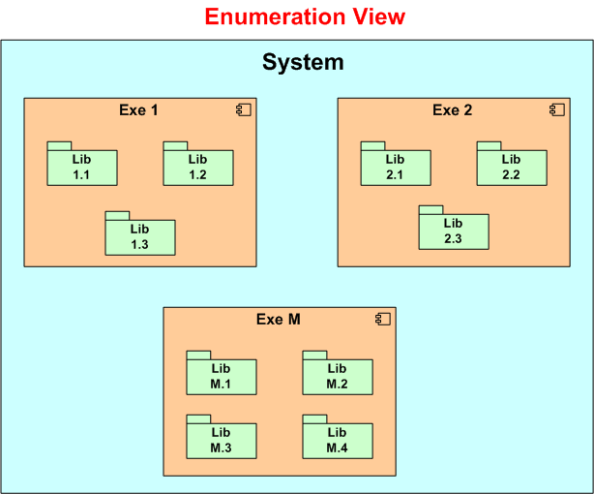

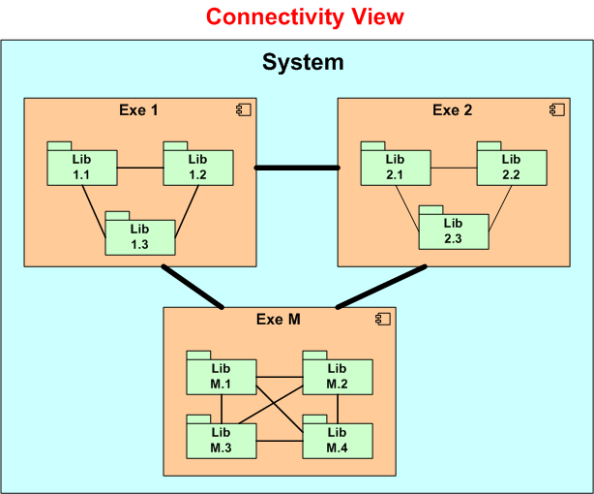

Assume we have a valuable, revenue-critical software system in operation. The figure below shows one nice and tidy, powerpoint-worthy way to model the system; as a static, enumerated set of executables and libraries.

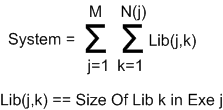

Given the model above, we can express the size of the system as:

Now, say we run a tool on the code base and it spits out a system size of 200K “somethings” (lines of code, function points, loops, branches, etc).

What does this 200K number of “somethings” absolutely tell us about the non-functional qualities of the system? It tells us absolutely nothing. All we know at the moment is that the system is operating and supporting the critical, revenue generating processes of our borg. Even relatively speaking, when we compare our 200K “somethings” system against a 100K “somethings” system, it still doesn’t tell us squat about the qualities of our system.

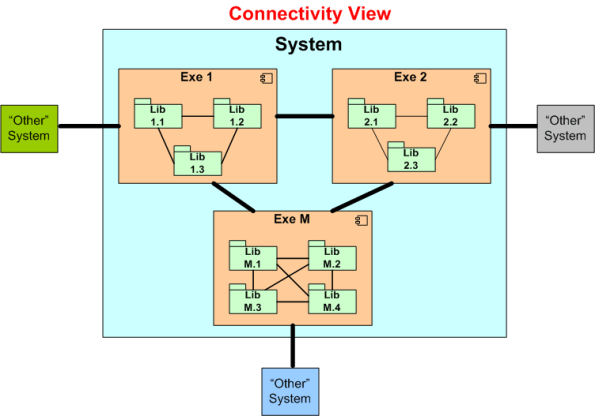

So, what’s missing here? One missing link is that our nice and tidy enumerations view and equation don’t tell us nuttin’ about what Russ Ackoff calls “the product of the interactions of the parts” (e.g Lib-to-Lib, Exe-Exe). To remedy the situation, let’s update our nice and tidy model with the part-to-part associations that enable our heap of individual parts to behave as a system:

Our updated model is still nice and tidy, but just not as nice and tidy as before. But wait! We are still missing something important. We’re missing a visual cue of our system’s interactions with “other” systems external to us; you know, “them”. The “them” we blame when something goes wrong during operation with the supra-system containing us and them.

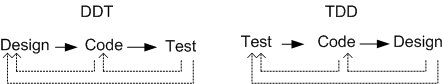

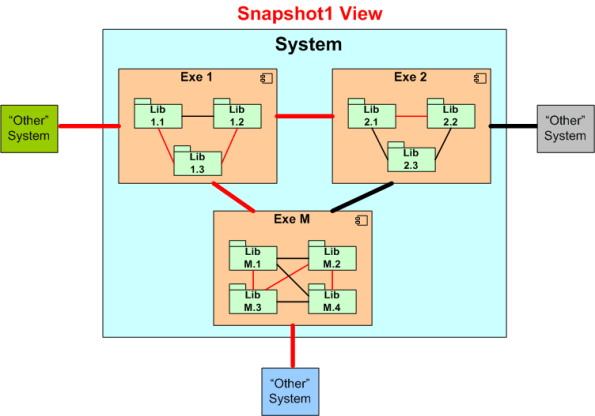

Our updated model is once again still nice and tidy, but just not as nice and tidy as before. Next, let’s take a single snapshot of the flow of (red) “blood” in our system at a given point of time:

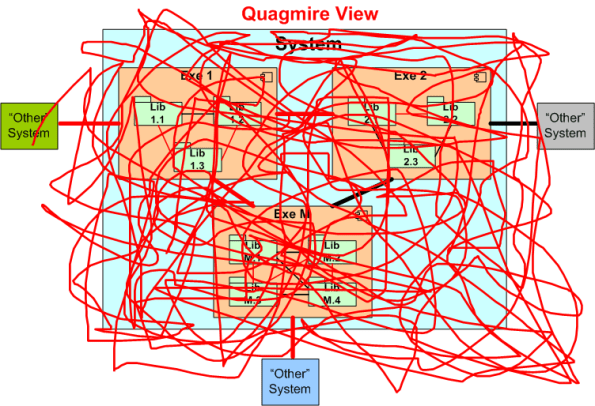

Finally, if we super-impose the astronomic number of all possible blood flow snapshots onto one diagram, we get:

D’oh! We’re not so nice and tidy anymore. Time for some heroic debugging on the bleeding mess. Is there a doctor in da house?