Archive

Well Architected

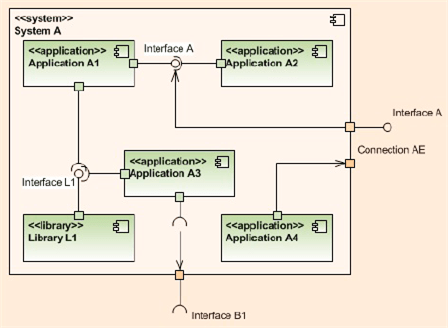

The UML component diagram below attempts to model the concept and characteristics of a well architected software-intensive system.

What other attributes of well architected/designed systems are there?

Without a sketched out blueprint like this, if you start designing and/or coding and cobbling together components randomly selected out of the blue and with no concept of layering/balancing, the chance that you end up will a well architected system is nil. You may get it “working” and have a nice GUI pasted on top of the beast, but under the covers it will be fragile and costly to extend/maintain/debug – unless a miracle has occurred.

If you or your management don’t know or care or are “allowed” to expose, capture, and continuously iterate on that architecture/design dwelling in your faulty and severely limited mind and memory, then you deserve what you get. Sadly, even though they don’t deserve it, every other stakeholder gets it too: your company, your customers, your fellow downstream maintainers, etc….

Levels, Components, Relationships

In the Crosstalk Journal, Michael Tarullo has written a nice little article on documenting software architectures. Using the concept of abstract levels (a necessary, but not sufficient tool, for understanding complex systems) and one UML component diagram per level, he presents a lightweight process for capturing big software system architecture decisions out of the ether.

Levels Of Abstraction

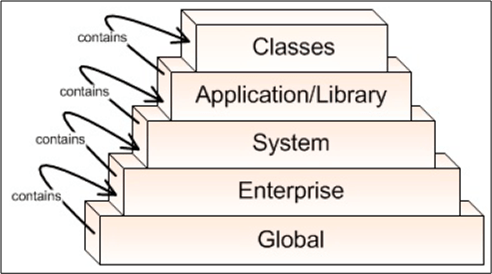

Mr. Tarullo’s 5 levels of abstraction are shown below (minor nit: BD00 would have flipped the figure upside down and shown the most abstract level (“Global“) at the top.

Components Within A Level

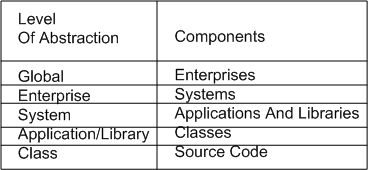

Since “architecture” focuses on the components of a system and the relationships between them, Michael defines the components of concern within each of his levels as:

(minor nit: because the word “system” is too generic and overused, BD00 would have chosen something like “function” or “service” for the third level instead).

Relationships

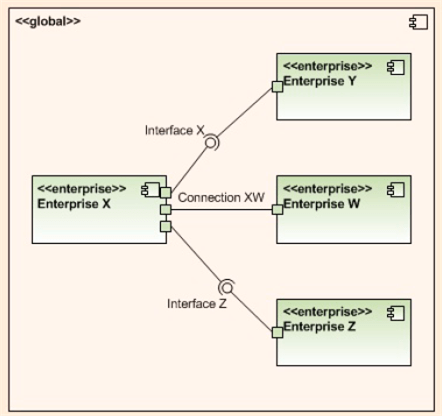

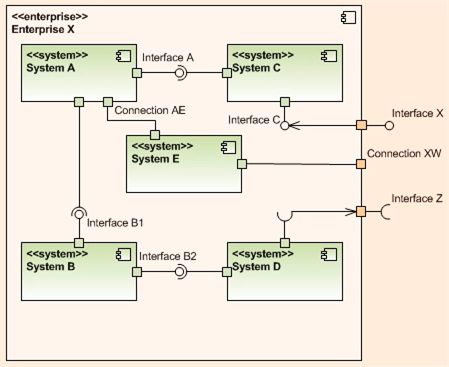

Within a given level of abstraction, Mr. Tarullo uses a UML component diagram with ports and ball/socket pairs to model connections, interfaces (provides/requires), and to bind the components together. He also maintains vertical system integrity by connecting adjacent levels together via ports/balls/sockets.

The three UML component diagrams below, one for each of the top, err bottom, three levels of abstraction in his taxonomy, nicely illustrate his lightweight levels plus UML component diagram approach to software architecture capture.

But what about the next 2 levels in the 5 level hierarchy: the Application/Library and Classes levels of the architecture? Mr. Tarullo doesn’t provide documentation examples for those, but it follows that UML class and sequence diagrams can be used for the Application/Library level, while activity diagrams and state machine diagrams can be good choices for the atomic class level.

Providing and vigilantly maintaining a minimal, lightweight stack of UML “blueprint” diagrams like these (supplemented by minimal “hole-filling” text) seems like a lower cost and more effective way to maintain system integrity, visibility, and exposure to critical scrutiny than generating a boatload of DOD template mandated write-once-read-never text documents, no?

Alas, if:

- you and your borg don’t know or care to know UML,

- you and your borg don’t understand or care to understand how to apply the complexity and ambiguity busting concepts of “layering and balancing“,

- your “official” borg process requires the generation of write-once-read-never, War And Peace sized textbook monstrosities,

then you, your product, your customers, and your borg are hosed and destined for an expensive, conflict filled future. (D’oh! I hate when that happens.)

Is It Safe?

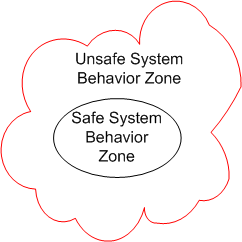

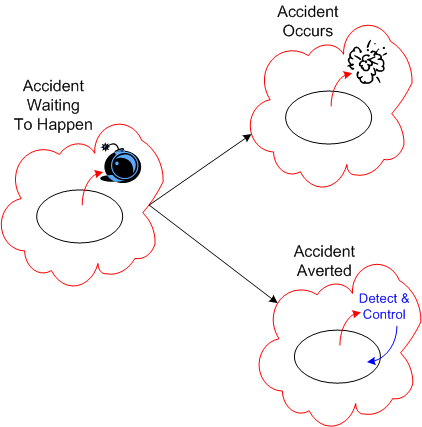

Assume that we place a large, socio-technical system designed to perform some safety-critical mission into operation. During the performance of its mission, the system’s behavior at any point in time (which emerges from the interactions between its people and machines), can be partitioned into 2 zones: safe and unsafe.

Since the second law of dynamics, like all natural laws, is impersonal and unapologetic, the system’s behavior will eventually drift into the unsafe system behavior zone over time. Combine the effects of the second law with poor stewardship on behalf of the system’s owner(s)/designer(s), and the frequency of trips into scary-land will increase.

Just because the system’s behavior veers off into the unsafe behavior zone doesn’t guarantee that an “unacceptable” accident will occur. If mechanisms to detect and correct unsafe behaviors are baked into the system design at the outset, the risk of an accident occurring can be lowered substantially.

Alas, “safety“, like all the other important, non-functional attributes of a system, is often neglected during system design. It’s unglamorous, it costs money, it adds design/development/test time to the sacred schedule. and the people who “do safety” are under-respected. The irony here is that after-the-accident, bolt-on, safety detection and control kludges cost more and are less trustworthy than doing it right in the first place.

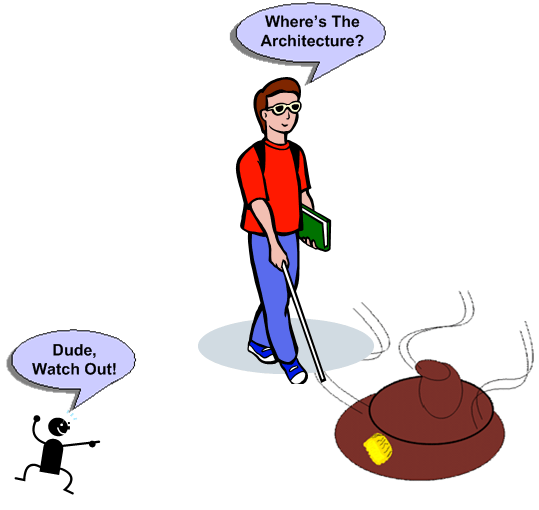

Invisible, Thus Irrelevant

A system that has a sound architecture is one that has conceptual integrity, and as (Fred) Brooks firmly states, “conceptual integrity is the most important consideration in system design”. In some ways, the architecture of a system is largely irrelevant to its end users. However, having a clean internal structure is essential to constructing a system that is understandable, can be extended and reorganized, and is maintainable and testable.

The above paragraph was taken from Booch et al’s delightful “Object-Oriented Analysis And Design With Applications“. BD00’s version of the bolded sentence is:

In some ways, the architecture of a system is largely irrelevant to its end users, its developers, and all levels of management in the development organization.

If the architecture is invisible because of the lack of a lightweight, widely circulated, communicated, and understood, set of living artifacts, then it can’t be relevant to any type of stakeholder – even a developer. As the saying goes: “out of site, out of mind“.

Despite the long term business importance of understandability, extendability, reorganizability, maintainability, and testability, many revenue generating product architectures are indeed invisible – unlike short term schedulability and budgetability; which are always highly visible.

A Bunch Of STIFs

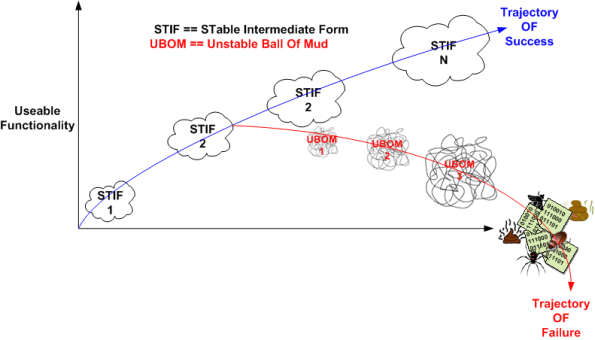

In “Object-Oriented Analysis and Design with Applications“, Grady Booch argues that a successful software architecture is layered, object-oriented, and evolves over time as a series of STIFs – STable Intermediate Forms. The smart and well liked BD00 agrees; and he adds that unsuccessful architectures devolve over time as a series of unacknowledged UBOMs (pronounced as “You Bombs“).

UBOMs are subtle creatures that, without caring stewardship, can unknowingly sneak up on you. Your first release or two may start out as a successful STIF or a small and unobtrusive UBOM. But then, since you’ve stepped into UBOM-land, it can grow into an unusable, resource-sucking abomination. Be careful, very careful….

“Who advocates for the product itself—its conceptual integrity, its efficiency, its economy, its robustness? Often, no one.” – Fred Brooks

“Dear Fred, when the primary thought held steadfast in everybody’s mind is “schedule is king” instead of “product is king“, of course no one will often advocate for the product.” – BD00

That’s All It Takes?

The MITRE corporation has a terrific web site loaded with information on the topic of system engineering. In spite of this, on the “Evolution of Systems Engineering” page, the conditions for system engineering success are laid out as:

- The system requirements are relatively well-established.

- Technologies are mature.

- There is a single or relatively homogeneous user community for whom the system is being developed.

- A single individual has management and funding authority over the program.

- A strong government program office capable of a peer relationship with the contractor.

- Effective architecting, including problem definition, evaluation of alternative solutions, and analysis of execution feasibility.

- Careful attention to program management and systems engineering foundational elements.

- Selection of an experienced, capable contractor.

- Effective performance-based contracting.

That’s it? That’s all it takes? Piece of cake. Uh, I think I’ll ship some parkas and igloo blueprints to hell to help those lost souls adapt to their new environment.

Benevolent Dictators And Unapologetic Aristocrats

The Editor in Chief of Dr. Dobb’s Journal, Andrew Binstock, laments about the “committee-ization” of programming languages like C, C++, and Java in “In Praise of Benevolent Language Dictators“:

Where the vision (of the language) is maintained by a single individual, quality thrives. Where committees determine features, quality declines inexorably: Each new release saps vitality from the language even as it appears to remedy past faults or provide new, awaited capabilities.

I think Andrew’s premise applies not only to languages, but it also applies to software designs, architectures, and even organizations of people. These constructs are all “systems” of dynamically interacting elements wired together in order to realize some purpose – not just bags of independent parts. As an example, Fred Brooks, in his classic book, “The Mythical Man-Month“, states:

To achieve conceptual integrity, a design must proceed from one mind or a small group of agreeing minds.

If a system is to have conceptual integrity, someone must control the concepts. That is an aristocracy that needs no apology.

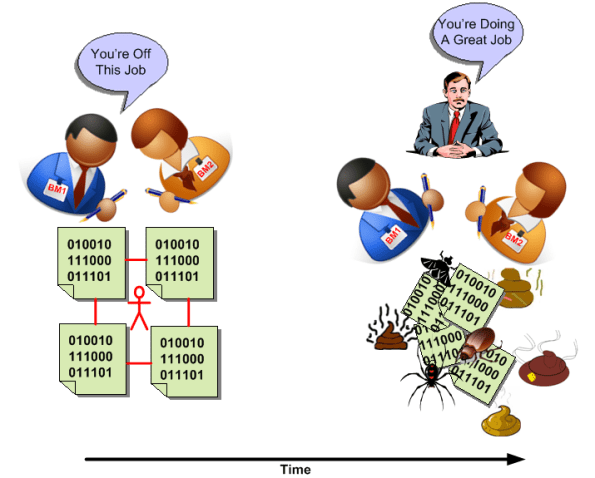

The greater the number of people involved in a concerted effort, the lower the coherency within, and the lower the consistency across, the results. That is, unless a benevolent dictator or unapologetic aristocrat is involved AND he/she is allowed to do what he/she decides must be done to ensure that conceptual integrity is preserved for the long haul.

Of course, because of the relentless increase in entropy guaranteed by the second law of thermodynamics, all conceptually integrated “closed systems” eventually morph into a disordered and random mess of unrelated parts. It’s just a matter of when, but if an unapologetic aristocrat who is keeping the conceptual integrity of a system intact leaves or is handcuffed by clueless dolts who have power over him/her, the system’s ultimate demise is greatly accelerated.

Findings And Recommendations

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare. Upon the authority of the charter granted to it by the Congress in 1863, the Academy has a mandate that requires it to advise the federal government on scientific and technical matters.

Via the publicly funded National Academies mailing list, I found out that the book “Critical Code: Software Producibility for Defense“ was available for free pdf download. Despite being committee written, the book is chock full of good “findings” and “recommendations” that are not only applicable to the DoD, but to laggard commercial companies as well.

Not surprisingly, because of the exponentially growing size of software-centric systems and the need for interoperability, “architecture” plays a prominent role in the book. Here are some of my favorite committee findings and recommendations:

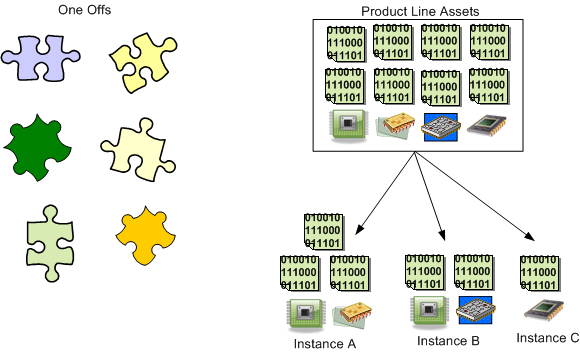

Finding 3-1: Industry leaders attend to software architecture as a first-order decision, and many follow a product-line strategy based on commitment to the most essential common software architectural elements and ecosystem structures.

Finding 3-2: The technology for definition and management of software architecture is sufficiently mature, with widespread adoption in industry. These approaches are ready for adoption by the DoD, assuming that a framework of incentives can be created in acquisition and development efforts.

Recommendation 3-2: This committee reiterates the past Defense Science Board recommendations that the DoD follow an architecture driven acquisition strategy, and, where appropriate, use the software architecture as the basis for a product-line approach and for larger-scale systems potentially involving multiple lead contractors.

The DoD funded Software Engineering Institute, located at Carnegie Mellon University, has produced a lot of good work on software product lines. Jan Bosch’s “Design and Use of Software Architectures: Adopting and Evolving a Product-Line Approach” and Chapters 14 and 15 in Bass, Clements, and Kazman’s “Software Architecture in Practice” are excellent sources of information. The stunning case study of Celsius Tech really drove the point home for me.

Distributed Functions, Objects, And Data

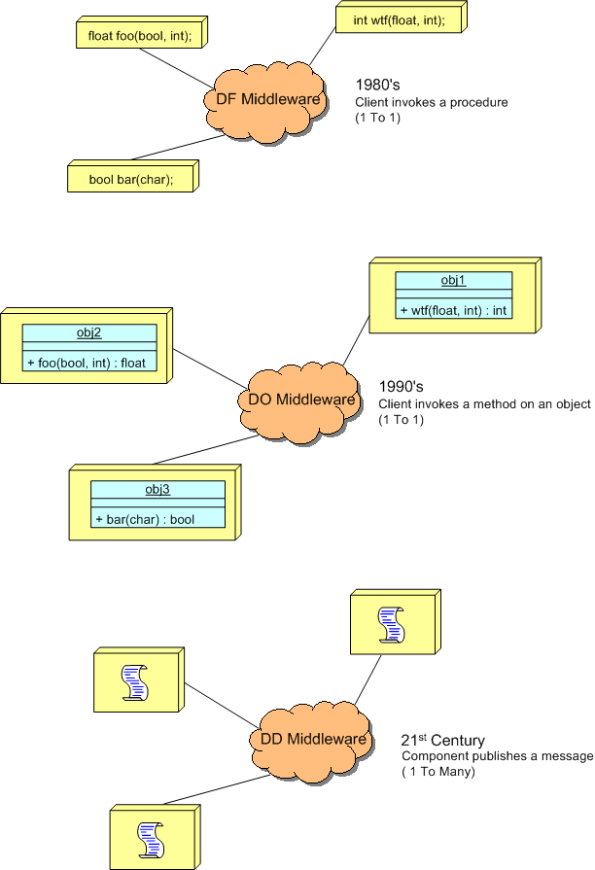

During a discussion on LinkedIn.com, the following distributed system communication architectural “styles” came up:

- DF == Distributed Functions

- DO == Distributed Objects

- DD == Distributed Data

I felt the need to draw a picture of them, so here it is:

The DF and DO styles are point-to-point, client-server oriented. Client functions invoke functions and object methods invoke object methods on remotely located servers.

The DD style is many-to-many, publisher-subscriber oriented. A publisher can be considered a sort of server and subscribers can be considered clients. The biggest difference is that instead of being client-triggered, communication is server-triggered in DD systems. When new data is available, it is published out onto the net for all subscribers to consume. The components in a DD system are more loosely coupled than those in DF and DO systems in that publishers don’t need to know anything (no handles or method signatures) about subscribers or vice versa – data is king. Nevertheless, there are applications where each of the three types excel over the other two.

Too Much Pressure

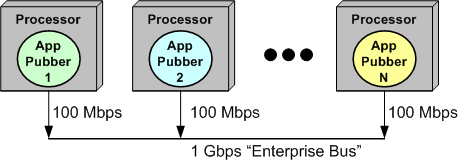

The figure below models an N node, “Enterprise Bus” (EB) connected, software-centric system.

Even though the “shared” EB supplies a raw, theoretical bandwidth of 1 Gbps to its connected user set, contention for frequent but temporary control of the bus among its clients increases as the number of message publisher (pubber) clients increases. Thus, the total effective bandwidth of the system as a whole decreases below the raw 1 Gbps rate as its utilization increases.

In the example, instead of accommodating up to 10, 100 Mbps clients, the increasing “back pressure” exerted by the bus under the duress imposed by multiple, “talky” (you know, wife-like) clients will throttle the per-pubber message send rate to well below 100 Mbps.

I recently found this out the hard way – through time-consuming testing and making sense out of the “unexpected” results I was getting. Bummer.