Archive

Shallmeisters, Get Over It.

If you pick up any reference article or book on requirements engineering, I think you’ll find that most “experts” in the field don’t obsess over “shalls”. They know that there’s much more to communicating requirements than writing down tidy, useless, fragmented, one line “shall” statements. If you don’t believe me, then come out of your warm little cocoon and explore for yourself. Here are just a few references:

http://www.amazon.com/Process-System-Architecture-Requirements-Engineering/dp/0932633412/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1257672507&sr=1-3

With the growing complexity of software-intensive systems that need to be developed for an org to remain sustainable and relevant, the so-called venerable “shall” is becoming more and more dinosaurish. Obviously, there will always be a place for “shalls” in the development process, but only at the most superficial and highest level of “requirements specification”; which is virtually useless to the hardware, software, network, and test engineers who have to build the system (while you watch from the sidelines and “wait” until the wrong monstrosity gets built so you can look good criticizing it for being wrong).

So, what are some alternatives to pulling useless one dimensional “shalls” out of your arse? How about mixing and matching some communication tools from this diversified, two dimensional menu:

- UML Class diagrams

- UML Use Case diagrams

- UML Deployment diagrams

- UML Activity diagrams

- UML State Machine diagrams

- UML Sequence diagrams

- Use Case Descriptions

- User Stories

- IDEF0 diagrams

- Data Flow Diagrams

- Control Flow Diagrams

- Entity-Relationship diagrams

- SysML Block Definition diagrams

- SysML Internal Block Definition diagrams

- SysML Requirements diagrams

- SysML Parametric diagrams

Get over it, add a second dimension to your view, move into this century, and learn something new. If not for your company, then for yourself. As the saying goes, “what worked well in the past might not work well in the future”.

Useless Cases

Despite the blasphemous title of this blarticle, I think that “use cases” are a terrific tool for capturing a system’s functional requirements out of the ether; for the right class of applications. Nevertheless, I agree with requirements “expert” Karl Wiegers, who states the following in “More About Software Requirements: Thorny Issues And Practical Advice“:

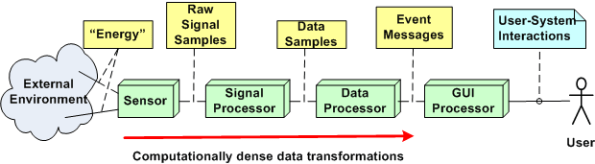

However, use cases are less valuable for projects involving data warehouses, batch processes, hardware products with embedded control software, and computationally intensive applications. In these sorts of systems, the deep complexity doesn’t lie in the user-system interactions. It might be worthwhile to identify use cases for such a product, but use case analysis will fall short as a technique for defining all the system’s behavior.

I help to define, specify, design, code, and test embedded (but relatively “big”) software-intensive sensor systems for the people-transportation industry. The figure below shows a generic, pseudo-UML diagram of one of these systems. Every component in the string is software-intensive. In this class of systems, like Karl says, “the deep complexity doesn’t lie in the user-system interactions”. As you can see, there’s a lot of special and magical “stuff” going on behind the GUI that the user doesn’t know about, and doesn’t care to know about. He/she just cares that the objects he/she wants to monitor show up on the screen and that the surveillance picture dutifully provided by the system is an accurate representation of what’s going on in the real world outside.

A list of typical functions for a product in this class may look like this:

- Display targets

- Configure system

- Monitor system operation

- Tag target

- Control system operation

- Perform RF signal filtering

- Perform signal demodulation

- Perform signal detection

- Perform false signal (e.g. noise) rejection

- Perform bit detection, extraction, and message generation

- Perform signal attribute (e.g. position, velocity) estimation

- Perform attribute tracking

Notice that only the top five functions involve direct user interaction with the product. Thus, I think that employing use cases to capture the functions required to provide those capabilities is a good idea. All the dirty and nasty”perform” stuff requires vertical, deep mathematical expertise and specification by sensor domain experts (some of whom, being “expert specialists”, think they are Gods). Thus, I think that the classical “old and unglamorous” Software Requirements Specification (SRS) method of defining the inputs/processing/output sequences (via UML activity diagrams and state machine diagrams) blows written use case descriptions out of the water in terms of Return On Investment (ROI) and value transferred to software developers.

Clueless Bozo Managers (BMs) and senior wannabe-a-BM developers who jump on the “use cases for everything” bandwagon (but may have never written a single use case description themselves) waste company time and money trying to bully “others” into ramming a square peg into a round hole. But they look hip, on the ball, and up to date doing it. And of course, they call it leadership.

SysML Diagram Headers

The Systems Modeling Language, SysML, is both an extension and a subset of the UML. SysML defines a “frame” that serves as the context for a given diagram’s content. As the diagram below shows, each frame contains a header compartment that houses 4 text elements which characterize the diagram. The two items in brackets are optional.

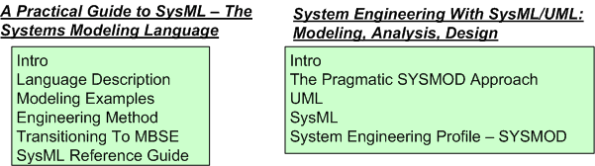

While learning the SysML, I was often confused as to the order of the header items and their meanings. My first thought when I saw the frame header was; “why are there so many freakin’ header entries; why not just one or two?”. I still get confused, but after studying a bunch of sample diagrams from System Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design and A Practical Guide to SysMLThe Systems Modeling Language, I think that I have almost figured it out.

With the aid of the two previously mentioned references, I constructed the table below. There are 9 enumerated SysML diagrams, so understanding what the “diagram kind” header field means is trivial. It’s the optional “model element” header item that continues to confuse me. As you can see from the table, the types of “model element(s)” that can appear within the first 6 diagrams are fixed and finite. However, the last three are open ended.

The problem for me is determining what the set of all “model element types” is. Is it a finite set of enumerations like the “diagram kind” header entry, or is it free form and ad-hoc? Does anyone know what the answer is?

SYSMOD Process Overview

Besides the systemic underestimation of cost and schedule, I believe that most project overruns are caused by shoddy front end system engineering (but that doesn’t happen in your org, right?). Thus, I’ve always been interested and curious about various system engineering processes and methods (I’ve even developed one myself – which was ignored of course 🙂 ). Tim Weilkiens, author of System Engineering with SysML/UML, has developed a very pragmatic and relatively lightweight system engineering process called SYSMOD. He uses SYSMOD as a framework to teach SysML in his book.

The figure below shows a summary of Mr. Weilkiens’s SYSMOD process in a 2 level table of activities. All of SYSMOD’s output artifacts are captured and recorded in a set of SysML diagrams, of course. Understandably, the SYSMOD process terminates at the end of the system design phase, after which the software and hardware design phases start. Like any good process, SYSMOD promotes an iterative development philosophy where the work at any downstream point in the process can trigger a revisit to previous activities in order to fix mistakes and errors made because of learning and new knowledge discovery.

The attributes that I like most about SYSMOD are that it:

- Seamlessly blends the best features of both object-oriented and structured analysis/design techniques together.

- Highlights data/object/item “flows” – which are usually relegated to the background as second class citizens in pure object-oriented methods.

- Starts with an outside-in approach based on the development of a comprehensive system context diagram – as opposed to just diving right into the creation of use cases.

- Develops a system glossary to serve as a common language and “root” of shared understanding.

How does the SYSMOD process compare to the ambiguous, inconsistent, bloated, one-way (no iterative loopbacks allowed), and high latency system engineering process that you use in your organization 🙂 ?

SysML Resources

Unlike the UML, the SysML has relatively few books and articles from which to learn the language in depth. The two (and maybe only?) SysML books that I’ve read are:

System Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design – Tim Weilkiens

A Practical Guide to SysMLThe Systems Modeling Language – Sanford Friedenthal; Alan Moore; Rick Steiner

IMHO, they are both terrific tools for learning the SysML and they’re both well worth the investment. Thus, I heartily recommend them both for anyone who’s interested in the language.

The books’ authors take different approaches to teaching the SysML. Even though the word “practical” is embedded in Friedenthal’s title, I think that Weilkiens book is less academic and more down to earth. Friendenthal takes a method-independent path toward communicating the SysML’s notation, syntax and semantics, while Weilkiens introduces his own pragmatic SYSMOD methodology as the primary teaching vehicle. Weilkiens examples seem less “dense” and more imbibable (higher drinkability :-)) than Friedenthal’s, but Friedenthal has examples from more electro-mechanical system “types”.

What I liked best about Weilkiens’s book is that in addition to the “what”, he does a splendid job explaining the “why” behind a lot of the SysML notation and symbology. You will easily conclude that he’s passionate about the subject and that he’s eager to teach you how to understand and use the SysML. Friedenthal’s book has an excellent and thorough SysML reference in an appendix. It’s great for looking up something you need to use but you forgot the details.

The Venerable Context Diagram

Since the method was developed before object-oriented analysis, I was weaned on structured analysis for system development. One of the structured analysis tools that I found most useful was (and still is) the context diagram. Developing a context diagram is the first step at bounding a problem and clearly delineating what is my responsibility and what isn’t. A context diagram publicly and visibly communicates what needs to be developed and what merely needs to be “connected to” – what’s external and what’s internal.

After learning how to apply object-oriented analysis, I was surprised and dismayed to discover that the context diagram was not included in the UML (or even more surprisingly, the SysML) as one of its explicitly defined diagrams. It’s been replaced by the Use Case Diagram. However, after reading Tim Weilkiens’s Systems Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design, I think that he solved the exclusion mystery.

….it wasn’t really fitting for a purely object-oriented notation like UML to support techniques from the procedural world. Fortunately the times when the procedural world and the object-oriented world were enemies and excluded each other are mostly overcome. Today, proven techniques from the procedural world are not rejected in object orientation, but further developed and integrated in the paradigm.

Isn’t it funny how the exclusive “either or” mindset dominates the inclusive “both and” mindset in the engineering world? When a new method or tool or language comes along, the older method gets totally rejected. The baby gets thrown out with the bathwater as a result of ego and dualistic “good-bad” thinking.

“Nothing is good or bad, thinking makes it so.” – William Shakespeare

Wide But Shallow, Narrow But Deep

I just “finished” (yeah,that’s right –> 100% done (LOL!)) exploring, discovering, defining, and specifying, the functional changes required to add a new feature to one of our pre-existing, software-intensive products. I’m currently deep in the trenches exploring and discovering how to specify a new set of changes required to add a second related feature to the same product. Unlike glamorous “Greenfield” projects where one can start with a blank sheet of paper, I’m constrained and shackled by having to wrestle with a large and poorly documented legacy system. Sound familiar?

The extreme contrast between the demands of the two project types is illuminating. The first one required a “wide but shallow” (WBS) analysis and synthesis effort while the current one requires a “narrow but deep” (NBD) effort. Both types of projects require long periods of sustained immersion in the problem domain, so most (all?) managers won’t understand this post. They’re too busy running around in ADHD mode acting important, goin’ to endless agenda-less meetings, and puttin’ out fires (that they ignited in the first place via their own neglect, ignorance, and lack of listening skills). Gawd, I’m such a self-righteous and bad person obsessed with trashing the guild of management 🙂 .

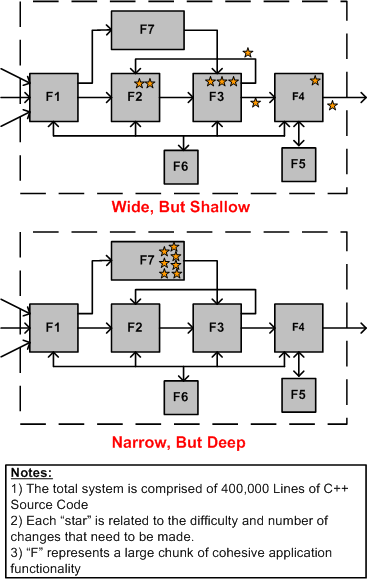

The figure below highlights the difference between WBS and NBD efforts for a “hypothetical” product enhancement project.

In WBS projects, the main challenge is hunting down all the well hidden spots that need to be changed within the behemoth. Missing any one of these change-spots can (and usually does) eat up lots of time and money down the road when the thing doesn’t work and the product team has to find out why. In NBD projects, the main obstacle to overcome is the acquisition of the specialized application domain knowledge and expertise required to perform localized surgery on the beast. Since the “search” for the change/insertion spots of an NBD effort is bounded and localized, an NBD effort is much lower risk and less frustrating than a WBS effort. This is doubly true for an undocumented system where studying massive quantities of source code is the only way to discover the change points throughout a large system. It’s also more difficult to guesstimate “time to completion” for a WBS project than it is for an NBD project. On the other hand, much more learning takes place in a WBS project because of the breadth of exposure to large swaths of the code base.

Assuming that you’re given a choice (I know that this assumption is a sh*tty one), which type of project would you choose to work on for your next assignment; a WBS project, or an NBD project? No cheatin’ is allowed by choosing “neither” 😉 .

Functional Allocation VIII

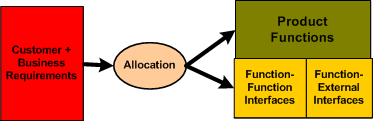

Typically, the first type of allocation work performed on a large and complex product is the shall-to-function (STF) allocation task. The figure below shows the inputs and outputs of the STF allocation process. Note that it is not enough to simply identify, enumerate, and define the product functions in isolation. An integral sub-activity of the process is to conjure up and define the internal and external functional interfaces. Since the dynamic interactions between the entities in an operational system (human or inanimate) give the system its power, I assert that interface definition is the most important part of any allocation process.

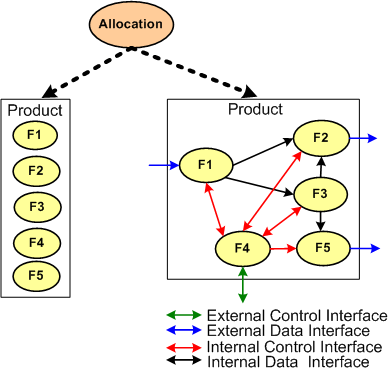

The figure below illustrates two alternate STF allocation outputs produced by different people. On the left, a bland list of unconnected product functions have been identified, but the functional structure has not been defined. On the right, the abstract functional product structure, defined by which functions are required to interact with other functions, is explicitly defined.

If the detailed design of each product function will require specialized domain expertise, then releasing a raw function list on the left to the downstream process can result in all kinds of counter productive behavior between the specialists whose functions need to communicate with each other in order to contribute to the product’s operation. Each function “owner” will each try to dictate the interface details to the “others” based on the local optimization of his/her own functional piece(s) of the product. Disrespect between team members and/or groups may ensue and bad blood may be spilled. In addition, even when the time consuming and contentious interface decision process is completed, the finished product will most likely suffer from a lack of holistic “conceptual integrity” because of the multitude of disparate interface specifications.

It is the lead system engineer’s or architect’s duty to define the function list and the interfaces that bind them together at the right level of detail that will preserve the conceptual integrity of the product. The danger is that if the system design owner goes too far, then the interfaces may end up being over-constrained and stifling to the function designers. Given a choice between leaving the interface design up to the team or doing it yourself, which approach would you choose?

Functional Allocation VII

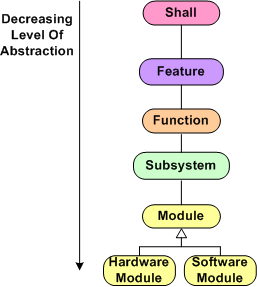

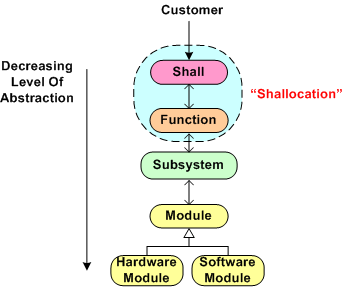

Here we are at blarticle number 7 on the unglamorous and boring topic of “Functional Allocation”. Once again, for a reference point of discussion, I present the hypothetical allocation tree below (your company does have a guidepost like this, doesn’t it?). In summary, product “shalls” are allocated to features, which are allocated to functions, which are allocated to subsystems, which are allocated to software and hardware modules. Depending on the size and complexity of the product to be built, one or more levels of abstraction can be skipped because the value added may not be worth the effort expended. For a simple software-only system that will run on Commercial-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) hardware, the only “allocation” work required to be performed is a shall-to-software module mapping.

During the performance of any intellectually challenging human endeavor, mistakes will be made and learning will take place in real-time as the task is performed. That’s how fallible humans work, period. Thus for the output of such a task like “allocation” to be of high quality, an iterative and low latency feedback loop approach should be executed. When one qualified person is involved, and there is only one “allocation” phase to be performed (e.g. shall-to-module), there isn’t a problem. All the mistake-making, learning, and looping activity takes place within a single mind at the speed of thought. For (hopefully) long periods of time, there are no distractions or external roadblocks to interrupt the performance of the task.

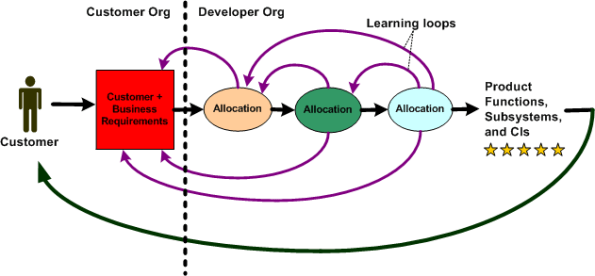

For a big and complex multi-technology product where multiple levels of “allocation” need to be performed and multiple people and/or specialized groups need to be involved, all kinds of socio-technical obstacles and roadblocks to downstream success will naturally emerge. The figure below shows an effective product development process where iteration and loop-based learning is unobstructed. Communication flows freely between the development groups and organizations to correct mistakes and converge on an effective solution . Everything turns out hunky dory and the customer gets a 5 star product that he/she/they want and the product meets all expectations.

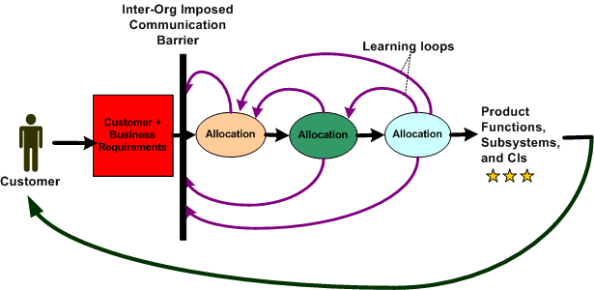

The figure below shows a dysfunctional product development process. For one reason or another, communication feedback from the developer org’s “allocation” groups is cut off from the customer organization. Since questions of understanding don’t get answered and mistakes/errors/ambiguities in the customer requirements go uncorrected, the end product delivered back to the customer underperforms and nobody ends up very happy. Bummer.

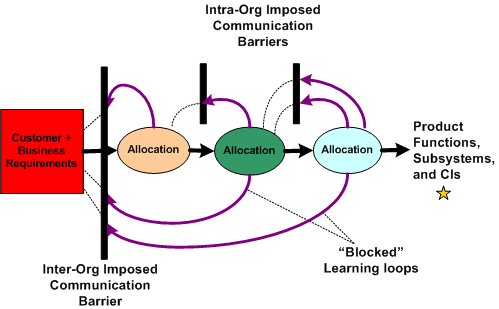

The figure below illustrates the worst possible case for everybody involved – a real mess. Not only do the customer and developer orgs not communicate; the “allocation” groups within the developer org don’t, or are prohibited from, communicating effectively with each other. The product that emerges from such a sequential linear-think process is a real stinker, oink oink. The money’s gone. the time’s gone, and the damn thang may not even work, let alone perform marginally.

Obviously, this situation is a massive failure of corpo leadership and sadly, I assert that it is the norm across the land. It is the norm because almost all big customer and developer orgs are structured as hierarchies of rank and stature with “standard” processes in place that require all kinds and numbers of unqualified people to “be in the loop” and approve (disapprove?) of every little step forward – lest their egos be hurt. Can a systemic, pervasive, baked-in problem like this be solved? If so, who, if anybody, has the ability to solve it? Can a single person overcome the massive forces of nature that keep a hierarchical ecosystem like this viable?

“The Biggest problem To Communication Is The Illusion That It Has Taken Place.” – George Bernard Shaw

Functional Allocation VI

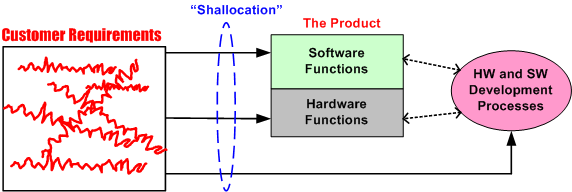

Every big system, multi-level, “allocation” process (like the one shown below) assumes that the process is initialized and kicked-off with a complete, consistent, and unambiguous set of customer-supplied “shalls”. These “shalls” need to be “shallocated” by a person or persons to an associated aggregate set of future product functions and/or features that will solve, or at least ameliorate, the customer’s problem. In my experience, a documented set of “shalls” is always provided with a contract, but the organization, consistency, completeness, and understandability of these customer level requirements often leaves much to be desired.

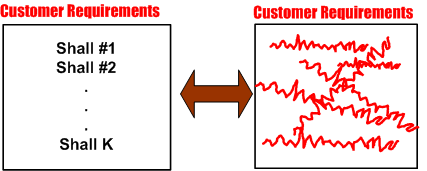

The figure below represents a hypothetical requirements mess. The mess might have been caused by “specification by committee”, where a bunch of people just haphazardly tossed “shalls” into the bucket according to different personal agendas and disparate perceptions of the problem to be solved.

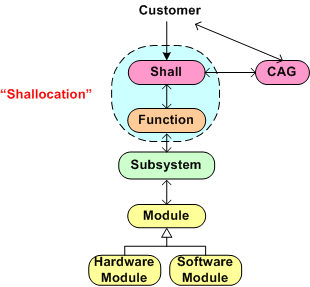

Given a fragmented and incoherent “mess”, what should be done next? Should one proceed directly to the Shall-To-Function (STF) process step? One alternative strategy, the performance of an intermediate step called Classify And Group (CAG), is shown below. CAG is also known as the more vague phrase; “requirements scrubbing”. As shown below, the intent is to remove as much ambiguity and inconsistency as possible by: 1) intelligently grouping the “shalls” into classification categories; 2) restructuring the result into a more usable artifact for the next downstream STF allocation step in the process.

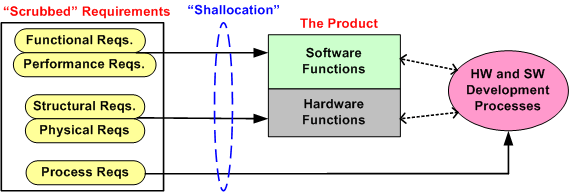

The figure below shows the position of the (usually “hidden” and unaccounted for) CAG process within the allocation tree. Notice the connection between the CAG and the customer. The purpose of that interface is so that the customer can clarify meaning and intent to the person or persons performing the CAG work. If the people performing the CAG work aren’t allowed, or can’t obtain, access to the customer group that produced the initial set of “shalls”, then all may be lost right out of the gate. Misunderstandings and ambiguities will be propagated downstream and end up embedded in the fabric of the product. Bummer city.

Once the CAG effort is completed (after several iterations involving the customer(s) of course), the first allocation activity, Shall-To-Function (STF), can then be effectively performed. The figure below shows the initial state of two different approaches prior to commencement of the STF activity. In the top portion of the figure, CAG was performed prior to starting the STF. In the bottom portion, CAG was not performed. Which approach has a better chance of downstream success? Does your company’s formal product development process explicitly call out and describe a CAG step? Should it?