Archive

SYSMOD Process Overview

Besides the systemic underestimation of cost and schedule, I believe that most project overruns are caused by shoddy front end system engineering (but that doesn’t happen in your org, right?). Thus, I’ve always been interested and curious about various system engineering processes and methods (I’ve even developed one myself – which was ignored of course 🙂 ). Tim Weilkiens, author of System Engineering with SysML/UML, has developed a very pragmatic and relatively lightweight system engineering process called SYSMOD. He uses SYSMOD as a framework to teach SysML in his book.

The figure below shows a summary of Mr. Weilkiens’s SYSMOD process in a 2 level table of activities. All of SYSMOD’s output artifacts are captured and recorded in a set of SysML diagrams, of course. Understandably, the SYSMOD process terminates at the end of the system design phase, after which the software and hardware design phases start. Like any good process, SYSMOD promotes an iterative development philosophy where the work at any downstream point in the process can trigger a revisit to previous activities in order to fix mistakes and errors made because of learning and new knowledge discovery.

The attributes that I like most about SYSMOD are that it:

- Seamlessly blends the best features of both object-oriented and structured analysis/design techniques together.

- Highlights data/object/item “flows” – which are usually relegated to the background as second class citizens in pure object-oriented methods.

- Starts with an outside-in approach based on the development of a comprehensive system context diagram – as opposed to just diving right into the creation of use cases.

- Develops a system glossary to serve as a common language and “root” of shared understanding.

How does the SYSMOD process compare to the ambiguous, inconsistent, bloated, one-way (no iterative loopbacks allowed), and high latency system engineering process that you use in your organization 🙂 ?

The Venerable Context Diagram

Since the method was developed before object-oriented analysis, I was weaned on structured analysis for system development. One of the structured analysis tools that I found most useful was (and still is) the context diagram. Developing a context diagram is the first step at bounding a problem and clearly delineating what is my responsibility and what isn’t. A context diagram publicly and visibly communicates what needs to be developed and what merely needs to be “connected to” – what’s external and what’s internal.

After learning how to apply object-oriented analysis, I was surprised and dismayed to discover that the context diagram was not included in the UML (or even more surprisingly, the SysML) as one of its explicitly defined diagrams. It’s been replaced by the Use Case Diagram. However, after reading Tim Weilkiens’s Systems Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design, I think that he solved the exclusion mystery.

….it wasn’t really fitting for a purely object-oriented notation like UML to support techniques from the procedural world. Fortunately the times when the procedural world and the object-oriented world were enemies and excluded each other are mostly overcome. Today, proven techniques from the procedural world are not rejected in object orientation, but further developed and integrated in the paradigm.

Isn’t it funny how the exclusive “either or” mindset dominates the inclusive “both and” mindset in the engineering world? When a new method or tool or language comes along, the older method gets totally rejected. The baby gets thrown out with the bathwater as a result of ego and dualistic “good-bad” thinking.

“Nothing is good or bad, thinking makes it so.” – William Shakespeare

Mista Level

“Design is an intimate act of communication between the designer and the designed” – W. L. Livingston

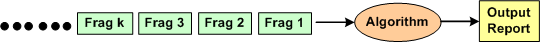

I’m currently in the process of developing an algorithm that is required to accumulate and correlate a set of incoming, fragmented messages in real-time for the purpose of producing an integrated and unified output message for downstream users.

The figure below shows a context diagram centered around the algorithm under development. The input is an unending, 24×7, high speed, fragmented stream of messages that can exhibit a fair amount of variety in behavior, including lost and/or corrupted and/or misordered fragments. In addition, fragmented message streams from multiple “sources” can be interlaced with each other in a non-deterministic manner. The algorithm needs to: separate the input streams by source, maintain/update an internal real-time database that tracks all sources, and periodically transmit source-specific output reports when certain validation conditions are satisfied.

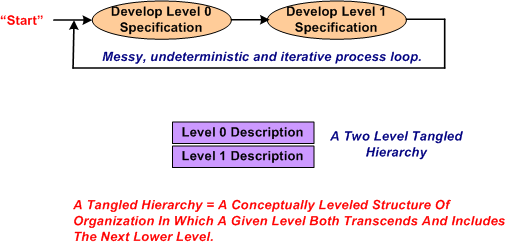

After studying literally 1000s of pages of technical information that describe the problem context that constrains the algorithm, I started sketching out and “playing” with candidate algorithm solutions at an arbitrary and subjective level of abstraction. Call this level of abstraction level 0. After looping around and around in the L0 thought space, I “subjectively decided” that I needed a second, more detailed but less abstract, level of definition, L1.

After maniacally spinning around within and between the two necessarily entangled hierarchical levels of definition, I arrived at a point of subjectively perceived stability in the design.

After receiving feedback from a fellow project stakeholder who needed an even more abstract level of description to communicate with other, non-development stakeholders, I decided that I mista level. However, I was able to quickly conjure up an L-1 description from the pre-existing lower level L0 and L1 descriptions.

Could I have started the algorithm development at L-1 and iteratively drilled downward? Could I have started at L1 and iteratively “syntegrated” upward? Would a one level-only (L-1, L0, or L1) specification be sufficient for all downstream stakeholders to use? The answers to all these questions, and others like them are highly subjective. I chose the jagged and discontinuous path that I traversed based on real-time situational assessment in the now, not based on some one-size-fits-all, step-by-step corpo approved procedure.

Wide But Shallow, Narrow But Deep

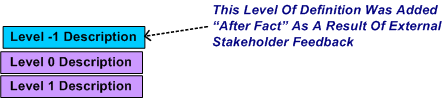

I just “finished” (yeah,that’s right –> 100% done (LOL!)) exploring, discovering, defining, and specifying, the functional changes required to add a new feature to one of our pre-existing, software-intensive products. I’m currently deep in the trenches exploring and discovering how to specify a new set of changes required to add a second related feature to the same product. Unlike glamorous “Greenfield” projects where one can start with a blank sheet of paper, I’m constrained and shackled by having to wrestle with a large and poorly documented legacy system. Sound familiar?

The extreme contrast between the demands of the two project types is illuminating. The first one required a “wide but shallow” (WBS) analysis and synthesis effort while the current one requires a “narrow but deep” (NBD) effort. Both types of projects require long periods of sustained immersion in the problem domain, so most (all?) managers won’t understand this post. They’re too busy running around in ADHD mode acting important, goin’ to endless agenda-less meetings, and puttin’ out fires (that they ignited in the first place via their own neglect, ignorance, and lack of listening skills). Gawd, I’m such a self-righteous and bad person obsessed with trashing the guild of management 🙂 .

The figure below highlights the difference between WBS and NBD efforts for a “hypothetical” product enhancement project.

In WBS projects, the main challenge is hunting down all the well hidden spots that need to be changed within the behemoth. Missing any one of these change-spots can (and usually does) eat up lots of time and money down the road when the thing doesn’t work and the product team has to find out why. In NBD projects, the main obstacle to overcome is the acquisition of the specialized application domain knowledge and expertise required to perform localized surgery on the beast. Since the “search” for the change/insertion spots of an NBD effort is bounded and localized, an NBD effort is much lower risk and less frustrating than a WBS effort. This is doubly true for an undocumented system where studying massive quantities of source code is the only way to discover the change points throughout a large system. It’s also more difficult to guesstimate “time to completion” for a WBS project than it is for an NBD project. On the other hand, much more learning takes place in a WBS project because of the breadth of exposure to large swaths of the code base.

Assuming that you’re given a choice (I know that this assumption is a sh*tty one), which type of project would you choose to work on for your next assignment; a WBS project, or an NBD project? No cheatin’ is allowed by choosing “neither” 😉 .

Sloppy and Undisciplined

If a company is sloppy and undisciplined in execution, then almost all of its value-creation resources (people, time, money) are constantly putting out legacy product fires instead of developing new products/services – creating wealth. Revenues and, especially, profits may suffer. “May” and not “will” you ask? Yes, I say. You see, if a company can get customers to continuously pay for the messes that the company has innocently but surely created, then financial performance may actually be perpetually “good”, or even “excellent”. Say what? Hoodwinking customers to pay for cleaning up your messes? What customers in their right mind would do this? Government customers who love to spend other people’s money, of course. Nice work if you can get it.

No Good Deed

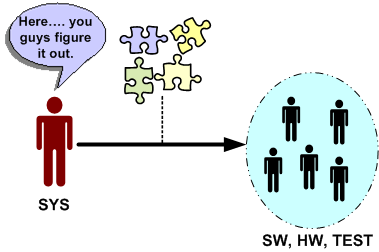

Let’s say that the system engineering culture at your hierarchically structured corpo org is such that virtually all work products handed off (down?) to hardware, software and test engineers are incomplete, inconsistent, fragmented, and filled with incomprehensible ambiguity. Another word that describes this type of low quality work is “camouflage”. Since it is baked into the “culture”, camouflage is expected, it’s taken for granted, and it’s burned into everyone’s mind that “that’s the way it is and that’s the way it always will be”.

Now, assume that someone comes along and breaks from the herd. He/she produces coherent, understandable, and directly usable outputs for the SW and HW and TEST engineers to make rapid downstream progress. How do you think the maverick system engineer would be treated by his/her peers? If you guessed: “with open arms”, then you are wrong. Statements like “that’s too much detail”, “it took too much time”, “you’re not supposed to do that”, “that’s not what our process says we should do”, etc, will reign down on the maverick. No good deed goes unpunished. Sic.

Why would this seemingly irrational and dysfunctional behavior occur? Because hirearchical corpo cultures don’t accept “change” without a fight, regardless of whether the change is good or bad. By embracing change, the changees have to first acknowledge the fact that what they were doing before the change wasn’t working. For engineers, or non-engineers with an engineering mindset of infallibility, this level of self-awareness doesn’t exist. If a maverick can’t handle the psychological peer pressure to return to the norm and produce shoddy work products, then the status quo will remain entrenched. Sadly but surely, this is what everyone wants, including management, and even more outrageously, the HW, SW, and TEST engineers. Bummer.

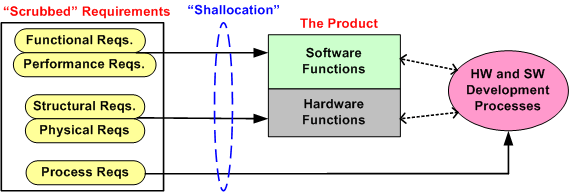

Functional Allocation VIII

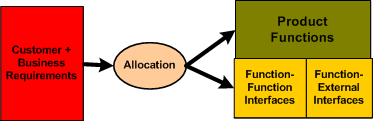

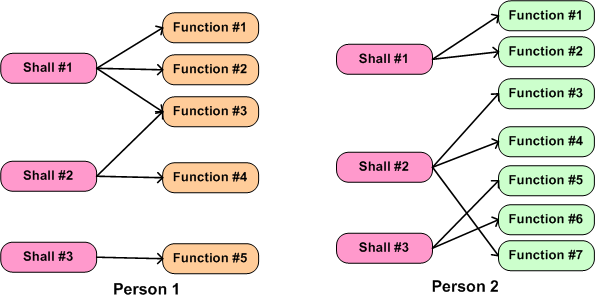

Typically, the first type of allocation work performed on a large and complex product is the shall-to-function (STF) allocation task. The figure below shows the inputs and outputs of the STF allocation process. Note that it is not enough to simply identify, enumerate, and define the product functions in isolation. An integral sub-activity of the process is to conjure up and define the internal and external functional interfaces. Since the dynamic interactions between the entities in an operational system (human or inanimate) give the system its power, I assert that interface definition is the most important part of any allocation process.

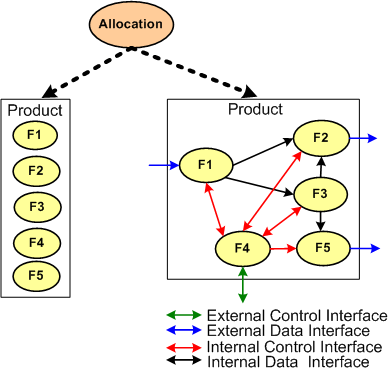

The figure below illustrates two alternate STF allocation outputs produced by different people. On the left, a bland list of unconnected product functions have been identified, but the functional structure has not been defined. On the right, the abstract functional product structure, defined by which functions are required to interact with other functions, is explicitly defined.

If the detailed design of each product function will require specialized domain expertise, then releasing a raw function list on the left to the downstream process can result in all kinds of counter productive behavior between the specialists whose functions need to communicate with each other in order to contribute to the product’s operation. Each function “owner” will each try to dictate the interface details to the “others” based on the local optimization of his/her own functional piece(s) of the product. Disrespect between team members and/or groups may ensue and bad blood may be spilled. In addition, even when the time consuming and contentious interface decision process is completed, the finished product will most likely suffer from a lack of holistic “conceptual integrity” because of the multitude of disparate interface specifications.

It is the lead system engineer’s or architect’s duty to define the function list and the interfaces that bind them together at the right level of detail that will preserve the conceptual integrity of the product. The danger is that if the system design owner goes too far, then the interfaces may end up being over-constrained and stifling to the function designers. Given a choice between leaving the interface design up to the team or doing it yourself, which approach would you choose?

Functional Allocation VI

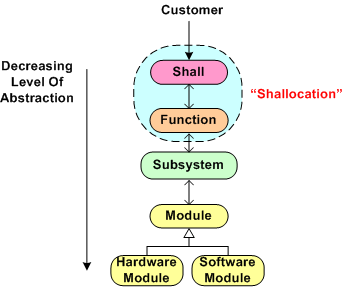

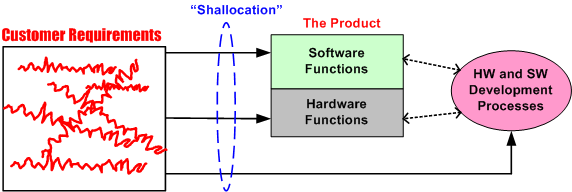

Every big system, multi-level, “allocation” process (like the one shown below) assumes that the process is initialized and kicked-off with a complete, consistent, and unambiguous set of customer-supplied “shalls”. These “shalls” need to be “shallocated” by a person or persons to an associated aggregate set of future product functions and/or features that will solve, or at least ameliorate, the customer’s problem. In my experience, a documented set of “shalls” is always provided with a contract, but the organization, consistency, completeness, and understandability of these customer level requirements often leaves much to be desired.

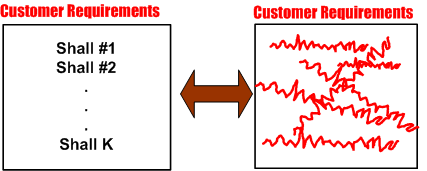

The figure below represents a hypothetical requirements mess. The mess might have been caused by “specification by committee”, where a bunch of people just haphazardly tossed “shalls” into the bucket according to different personal agendas and disparate perceptions of the problem to be solved.

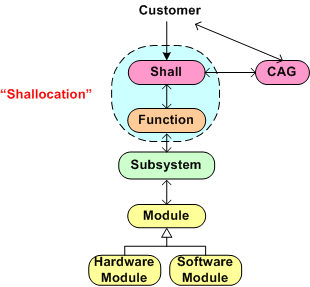

Given a fragmented and incoherent “mess”, what should be done next? Should one proceed directly to the Shall-To-Function (STF) process step? One alternative strategy, the performance of an intermediate step called Classify And Group (CAG), is shown below. CAG is also known as the more vague phrase; “requirements scrubbing”. As shown below, the intent is to remove as much ambiguity and inconsistency as possible by: 1) intelligently grouping the “shalls” into classification categories; 2) restructuring the result into a more usable artifact for the next downstream STF allocation step in the process.

The figure below shows the position of the (usually “hidden” and unaccounted for) CAG process within the allocation tree. Notice the connection between the CAG and the customer. The purpose of that interface is so that the customer can clarify meaning and intent to the person or persons performing the CAG work. If the people performing the CAG work aren’t allowed, or can’t obtain, access to the customer group that produced the initial set of “shalls”, then all may be lost right out of the gate. Misunderstandings and ambiguities will be propagated downstream and end up embedded in the fabric of the product. Bummer city.

Once the CAG effort is completed (after several iterations involving the customer(s) of course), the first allocation activity, Shall-To-Function (STF), can then be effectively performed. The figure below shows the initial state of two different approaches prior to commencement of the STF activity. In the top portion of the figure, CAG was performed prior to starting the STF. In the bottom portion, CAG was not performed. Which approach has a better chance of downstream success? Does your company’s formal product development process explicitly call out and describe a CAG step? Should it?

Functional Allocation V

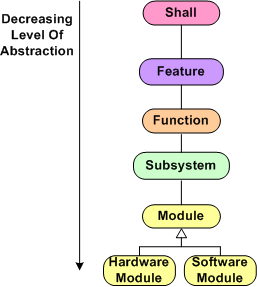

Holy cow! We’re up to the fifth boring blarticle that delves into the mysterious nature of “Functional Allocation”. Let’s start here with the hypothetical 6 level allocation reference tree that was presented earlier.

Assume that our company is smart enough to define and standardize a reference tree like this one in their formal process documentation. Now, let’s assume that our company has been contracted to develop a Large And Complex (LAC) software-intensive system. My fuzzy and un-rigorous definition of large and complex is:

“The product has, (or will have after it’s built) lots of parts, many different kinds of parts, lots of internal and external interfaces, and lots of different types of interfaces”.

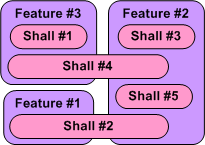

The figure below shows a partial result of step one in the multi-level process; the Shall-To-Feature (STF) allocation process. Given a set of 5 customer-supplied abstract “shalls”, someone has made the design decisions that led to the identification and definition of 3 less-abstract features that the product must provide in order to satisfy the customer shalls.We’ve started the movement from the abstract to the less abstract.

Just imagine what the model below would look like in the case where we had 100s of shalls to wrestle with. How could anyone possibly conclude up front that the set of shalls have been completely covered by the feature set? At this stage of the game, I assert that you can’t. You have to make a commitment and move on. In all likelihood, the initial STF allocation result won’t work. Thus, if your process doesn’t explicitly include the concept of “iterating on mistakes made and on new knowledge gained” as the product development process lurches forward, you’ll get what you deserve.

Note that in the simple example above, there is no clean and proper one-to-one STF mapping and there are 2 cross-cutting “shalls”. Also, note that there is no logical rule or mathematical formula grounded in physics that enables a shallocator (robot or human) to mechanically compute an “optimum” feature set and perform the corresponding STF allocation. It’s abstract stuff, and different qualified people will come up with different designs. Management, take heed of that fact.

So, given the initial finished STF allocation output (recorded and made accessible and visible for others to evaluate, of course) how was it arrived at? Could the effort be codified in a step-by-step Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) so that it can be classified as “repeatable and predictable”? I say no, regardless of what bureaucrats and process managers who’ve never done it themselves think. What about you, what do you think?

Functional Allocation IV

Part IV is a continuation of our discussion regarding the often misunderstood and ill-defined process of “functional allocation”. In this part we’ll, explore the nature of the “shallocation” task, some daunting organizational obstacles to its successful completion, and the dependency of quality of output on the specific persons assigned (or allocated?) to the task.

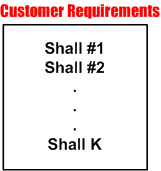

If you can find one, the process description of functional allocation starts out assuming that a human allocator is given a linear text list, which maybe quite large, of “shalls” supplied by an external customer or internal customer advocate. Of course, these “shalls” are also assumed to be unambiguous, consistent, non-contradictory, complete, and intelligently organized (yeah, right).

My personal experience has been that the “shalls” are usually strewn all over the place and the artifact that holds them is severely lacking in what Fred Brooks called “conceptual integrity”. Sometimes, the “shalls” seem to randomly jump back and forth from high level abstractions down to physical properties – a mixed mess hacked together by a group of individuals with different agendas. In addition, some customers (especially government bureaucracies) often impose some overconstraining “shalls” on the structure of the development team and the processes that the team is required to use during the development of the solution to their problem (control freaks). Even worse, in order to project a false image of “we know what we’re doing” infallibility and the fact that they don’t have to do the hard value-creation work themselves, helpful managers of developer orgs often discourage, or downright prevent, clarification questions from being asked of the customer by development team members. All communciations must be filtered through the “proper” chain of command, regardless of how long it takes or whether technical questions get filtered and distorted to incomprehensibilty through non-technical wonks with a fancy title. Bummer.

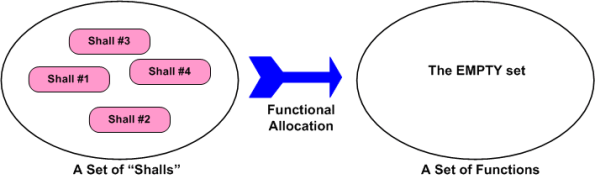

Because we want to move forward with this discussion, assume the unassume-able; the customer “shall” list is perfectly complete and understood by the developer org’s system engineers. What’s next? The figure below shows the “initialization” state. The perfect list of “shalls” must be shallocated to a set of non-existent product functions. Someone, somehow, has got to conceive of and define the set of functions and the logical inter-function connectivity that will satisfy the perfectly clear and complete “shalls” list.

Piece of cake, right? The task of shallocation is so easy and well described by many others (yeah, right), that I won’t even waste any e-space giving the step by step recipe for it. The figure below shows the logical functional structure of the product after the trivial shallocation process is completed by a robot or an expensive automated software tool.

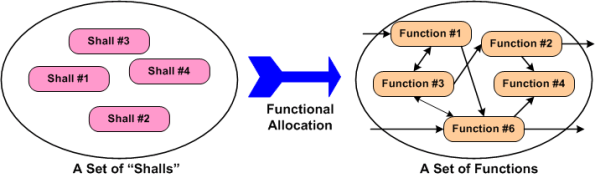

Realistically, in today’s world the shallocation process can’t be automated away, and it’s highly person-specific. As the example in the figure below shows, given the same set of “shalls”, two different people will, “after a miracle occurs”, likely conjure up a different set of functions in an attempt to meet the customer’s product requirements. Not only can the number of functions, and the internal nature of each function be different, the allocation of shalls-to-functions may be different. Expecting a pristine, one-to-one shall-to-function mapping is unrealistically utopian.

What the example below doesn’t show is the person-specific creation of the inter-function logical connectivity (see the right portion of the previous figure) that is required for the product system to “work”. After all, a set of unconnected functions, much like a heap of car parts, doesn’t do anything but sit there looking sophisticated. It’s the interactions between the functions during operation that give a product it’s power to maybe, just maybe, solve a customer’s problem.

The purpose of part IV in this seemingly endless series of blarticles on “functional allocation” was to basically point out the person-specific nature of the first step in a multi-level nested allocation process. It also hinted at some obstacles that conspire to thwart the effective performance of the task of shallocation.