Archive

(Dys)functional Managers

IMHO, “functional” engineering managers (e.g. software, hardware, systems, test, etc) should be charged with: developing their people, removing obstacles to their progress, ensuring that tools and training are available, and streamlining bloated processes so that their people can work more efficiently and produce higher quality work outputs. Abdicating these responsibilities makes these dudes (dys)functional bozo managers in my (and maybe only my) eyes.

It really blows my mind when (dys)functional managers are allowed to anoint themselves “chief architect” over and above individual product team functional leads. It’s doubly annoying and counterproductive to an org when these BMs don’t work hands-on with any of the org’s products day-to-day, and they haven’t done any technical design work in this millenium. If I was their next level manager (and not a BM myself so that I could actually see the problem), I’d, as textbook clone managers love to say, “aggressively address” the BM problem by making it crystal clear what their real job is. I’d follow up by periodically polling the BM’s people directly to evaluate how well the BM is performing. Of course, I’m not fit to lead anyone, so you should totally ignore what I say :^)

Get The Hell Out Of There!

When a highly esteemed project manager starts a project kickoff meeting with something like: “Our objective is to develop the cheapest product and get it out to the customer as quickly as possible to minimize the financial risk to the company“, and nobody in attendance (including you) bats an eyelash or points out the fact that the proposed approach conflicts with the company’s core values, my advice to you is to do as the title of this post says: “get the hell out of there (you spineless moe-foe)!”. Conjure up your communication skills and back out of the project – in a politically correct way, of course. If you get handcuffed into the job via externally imposed coercion or guilt inducing torture techniques (a.k.a corpo waterboarding), then, then, then……. good luck sucka! I’ll see you in hell.

The bitterness of poor system performance remains long after the sweetness of low prices and prompt delivery are forgotten. – Jerry Lim

Abstraction

Jeff Atwood, of “Coding Horror” fame, once something like “If our code didn’t use abstractions, it would be a convoluted mess“. As software projects get larger and larger, using more and more abstraction technologies is the key to creating robust and maintainable code.

Using C++ as an example language, the figure below shows the advances in abstraction technologies that have taken place over the years. Each step up the chain was designed to make large scale, domain-specific application development easier and more manageable.

The relentless advances in software technology designed to keep complexity in check is a double-edged sword. Unless one learns and practices using the new abstraction techniques in a sandbox, haphazardly incorporating them into the code can do more damage than good.

One issue is that when young developers are hired into a growing company to maintain legacy code that doesn’t incorporate the newer complexity-busting language features, they become accustomed to the old and unmaintainable style that is encrusted in the code. Because of schedule pressure and no company time allocated to experiment with and learn new language features, they shoe horn in changes without employing any of the features that would reduce the technical debt incurred over years of growing the software without any periodic refactoring. The problem is exacerbated by not having a set of regression tests in place to ensure that nothing gets broken by any major refactoring effort. Bummer.

Partial Training

If you’re gonna spend money on training your people, do it right or don’t do it at all.

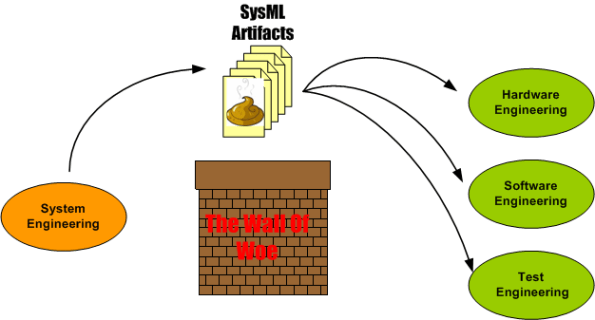

Assume that a new project is about to start up and the corpo hierarchs decide to use it as a springboard to institutionalizing SysML into its dysfunctional system engineering process. The system engineering team is then sent to a 3 day SysML training course where they get sprayed by a fire hose of detailed SysML concepts, terminology, syntax, and semantics.

Armed with their new training, the system engineering team comes back, generates a bunch of crappy, incomplete, ambiguous, and unhelpful SysML artifacts, and then dumps them on the software, hardware, and test teams. The receiving teams, under the schedule gun and not having been trained to read SysML, ignore the artifacts (while pretending otherwise) and build an unmaintainable monstrosity that just barely works – at twice the cost they would would have spent if no SysML was used. The hierarchs, after comparing product development costs before and after SysML training, declare SysML as a failure and business returns to the same old, same old. Bummer.

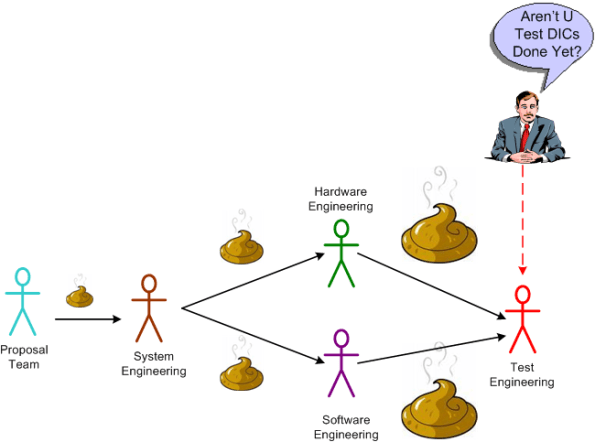

Poor Test Dudes

Out of all the types of DICs in a textbook CCH, the poor test dudes always have the roughest go of it. Out of necessity, they have mastered the art of nose pinching.

I’m Finished

I just finished (100% of course <-LOL!) my latest software development project. The purpose of this post is to describe what I had to do, what outputs I produced during the effort, and to obtain your feedback – good or bad.

The figure below shows a simple high level design view of an existing real-time, software-intensive, revenue generating product that is comprised of hundreds of thousands of lines of source code. Due to evolving customer requirements, a major redesign and enhancement of the application layer functionality that resides in the Channel 3 Target Extractor is required.

The figure below shows the high level static structure of the “Enhanced Channel 3 Target Extractor” test harness that was designed and developed to test and verify that the enhanced channel 3 target extractor works correctly. Note that the number of high level conceptual test infrastructure classes is 4 compared to the lone, single product class whose functionality will be migrated into the product code base.

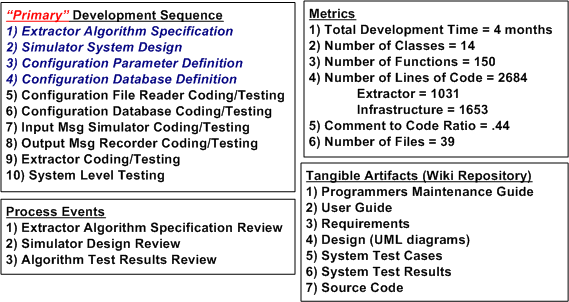

The figure below shows a post-project summary in terms of: the development process I used, the process reviews I held, the metrics I collected, and the output artifacts that I produced. Summarizing my project performance via the often used, simple-minded metric that old school managers love to use; lines of code per day, yields the paltry number of 22.

Since my average “velocity” was a measly 22 lines of code per day, do you think I underperformed on this project? What should that number be? Do you summarize your software development projects similar to this? Do you just produce source code and unit tests as your tangible output? Do you have any idea what your performance was on the last project you completed? What do you think I did wrong? Should I have just produced source code as my output and none of the other 6 “document” outputs? Should I have skipped steps 1 through 4 in my development process because they are non-agile “documentation” steps? Do you think I followed a pure waterfall process? What say you?

Linear Culture, Iterative Culture

A Linear Think Technical Culture (LTTC) equates error with sin. Thus, iteration to remove errors and mistakes is “not allowed” and schedules don’t provide for slack time in between sprints to regroup, reflect and improve quality . In really bad LTTCs, errors and mistakes are covered up so that the “perpetrators” don’t get punished for being less than perfect. An Iterative Think Technical Culture (ITTC) embraces the reality that people make mistakes and encourages continuous error removal, especially on intellectually demanding tasks.

The figure below shows the first phase of a hypothetical two phase project and the relative schedule performance of the two contrasting cultures. Because of the lack of “Fix Errors” periods, the LTTC reaches the phase I handoff transition point earlier .

The next figure shows the schedule performance of phase II in our hypothetical project. The LTTC team gets a head start out of the gate but soon gets bogged down correcting fubars made during phase I. The ITTC team, having caught and fixed most of their turds much closer to the point in time at which they were made, finishes phase II before the LTTC team hands off their work to the phase III team (or the customer if phase II is that last activity in the project).

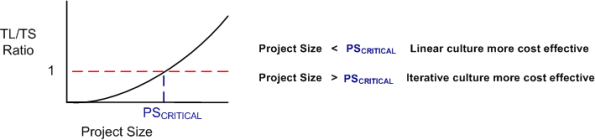

It appears that project teams with an ITTC always trump LTTC teams. However, if the project complexity, which is usually intimately tied to its size, is low enough, an LTTC team can outperform an ITTC team. The figure below illustrates a most-likely-immeasurable “critical project size” metric at which ITTC teams start outperforming LTTC teams.

The mysterious critical-project-size metric can be highly variable between companies, and even between groups within a company. With highly trained, competent, and experienced people, an LTTC team can outperform an ITTC team at larger and larger critical project sizes. What kind of culture are you immersed in?

What The Hell’s A Unit?

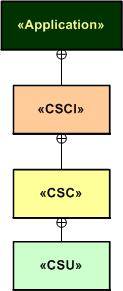

- CSCI = Computer Software Configuration Item

- CSC = Computer Software Component

- CSU = Computer Software Unit

In my industry (aerospace and defense), we use the abstract, programming-language-independent terms CSCI, CSC, and CSU as a means for organizing and conversing about software architectures and designs. The terms go way back, and I think (but am not sure) that someone in the Department Of Defense originally conjured them up.

The SysML diagram below models the semantic relationships between these “formal” terms. An application “contains” one or more CSCIs, each of which which contains one or more CSCs, each of which contains one or more CSUs. If we wanted to go one level higher, we could say that a “system” contains one or more Applications.

In my experience, the CSCI-CSC-CSU tree is almost never defined and recorded for downstream reference at project start. Nor is it evolved or built-up as the project progresses. The lack of explicit definition of the CSCs and, especially the CSUs, has often been a continuous source of ambiguity, confusion, and mis-communication within and between product development teams.

“The biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” – George Bernard Shaw.

A consequence of not classifying an application down to the CSU level is the classic “what the hell’s a unit?” problem. If your system is defined as just a collection of CSCIs comprised of hundreds of thousands of lines of source code and the identification of CSCs and CSUs is left to chance, then a whole CSCI can be literally considered a “unit” and you only have one unit test per CSCI to run (LOL!)

In preparation for an idea that follows, check out the language-specific taxonomies that I made up (I like to make stuff up so people can rip it to shreds) for complex C++ and Java applications below. If your app is comprised of a single, simple process without any threads or tasks (like they teach in school and intro-programming books), mentally remove the process and thread levels from the diagram. Then just plop the Application level right on top of the C++ namespace and/or the Java package levels.

To solve, or at least ameliorate the “what the hell’s a unit?” problem, I gently propose the consideration of the following concrete-to-abstract mappings for programs written in C++ and Java. In both languages, each process in an application “is a” CSCI and each thread within a process “is a” CSC. A CSU “is a” namespace (in C++) or a package (in Java).

I think that adopting a map such as this to use as a standard communication tool would lead to fewer mis-communications between and among development team members and, more importantly, between developer orgs and customer orgs that require design artifacts to employ the CSCI/CSC/CSU terminology.

As just stated, the BD00 proposal maps a C++ namespace or a java package into the lowest level element of abstract organization – the CSU. If that level of granularity is too coarse, then a class, or even a class member function (method in Java), can be designated as a CSU (as shown below). The point is that each company’s software development organization should pick one definition and use it consistently on all their projects. Then everyone would have a chance of speaking a common language and no one would be asking, “what the hell’s a freakin’ unit?“.

So, “What the hell’s a unit?” in your org? A member function? A class? A namespace? A thread? A process? An application? A system?

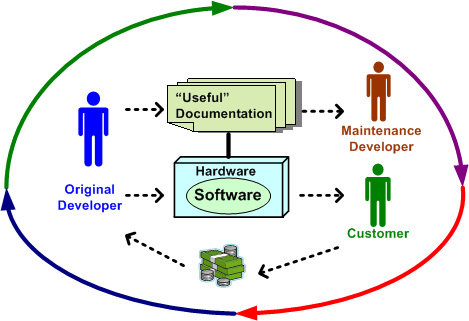

Working Software, Working Documents

Documentation is a love letter that you write to your future self – Damian Conway

The agile software development community rightly says that the best measure of progress is demonstrate-able working software that is delivered incrementally and frequently to customers for their viewing and using pleasure. For the most part, and for good reasons based on historical evidence, agile proponents eschew documentation. Nevertheless, big bureaucratic customers like national and state governments often, very often, require and expect comprehensive documentation from their vendors. Thus, zealot agilist juntas essentially ignore the requirements of a large and deep-pocketed customer base.

It’s software development, not documentation development – Scott Ambler

What if we can bring big, stodgy, conservative, and sometimes-paranoid customers halfway? Why not try to convince them of the merits of delivering frequent and incrementally improving requirements, design, construction, and user documents along with the working software builds? If we pay as we go, incrementally doing a little documentation, doing a little software coding, and doing a little testing instead of piling on the documentation up front or frantically kludging the documents together after the fact, wouldn’t the end result would turn out better?

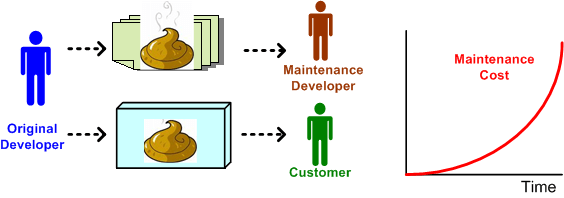

A consequence of generating crappy documentation for big, long-lived systems is the high cost of downstream maintenance. Dumping hundreds of thousands of lines of code onto the maintenance team without handing them synchronized blueprints is an irresponsible act of disrespect to both the team and the company. Without being able to see the forest for the trees, maintenance teams, which are usually comprised of young and impressionable developers, get frustrated and inject kludged up implementations of new features and bug fixes into the product. Bad habits are formed, new product versions get delivered later and later, and maintenance costs grow higher and higher. Bummer.

Scaleability

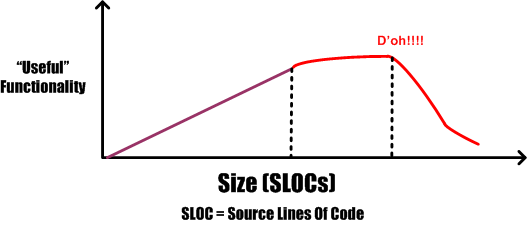

The other day, a friend suggested plotting “functionality versus size” as a potentially meaningful and actionable measure of software development process prowess. The figure below is an unscientific attempt to generically expand on his idea.

Assume that the graph represents the efficiency of three different and unknown companies (note: since I don’t know squat and I am known for “making stuff up”, take the implications of the graph with a grain of salt). Because it’s well known by industry experts that the complexity of a software-intensive product increases at a much faster rate than size, one would expect the “law of diminishing returns” to kick in at some point. Now, assume that the inflection point where the law snaps into action is represented by the intersection of the three traces in the graph. The red company’s performance clearly shows the deterioration in efficiency due to the law kicking in. However, the other two companies seem to be defying the law.

How can a supposedly natural law, which is unsentimental and totally indifferent to those under its influence, be violated? In a word, it’s “scaleability“. The purple and green companies have developed the practices, skills, and abilities to continuously improve their software development processes in order to keep up with the difficulty of creating larger and more complex products. Unlike the red company, their processes are minimal and flexible so that they can be easily changed as bigger and bigger products are built.

Either quantitatively or qualitatively, all growing companies that employ unscaleable development processes eventually detect that they’ve crossed the inflection point – after the fact. Most of these post-crossing discoverers panic and do the exact opposite of what they need to do to make their processes scaleable. They pile on more practices, procedures, forms-for-approval, status meetings, and oversight (a.k.a. managers) in a misguided attempt to reverse deteriorating performance. These ironic “process improvement” actions solidify and instill rigidity into the process. They handcuff and demoralize development teams at best, and trigger a second inflection point at worst:

More meetings plus more documentation plus more management does not equal more success. – NASA SEL