Archive

Plan, Plan, Plan…. Blah, Blah, Blah.

Preface

People followed Martin Luther King of their own free will because he had a dream, not a plan. – Simon Sinek

On the other hand, know-it-all business school trained weenies will profess (in a patriachical and condescending tone):

Failing to plan is planning to fail – Unknown

Irrelevant Intro

When I started this relatively loooong blarticle, I had no freakin’ idea where it would go but I followed where it led me. Led by the unknown into the unknown – it was the keystone cops leading the three (nyuk nyuk nyuk) stooges (whoo, whoo, whoo, boink, plunk, pssst!).

As usual, I didn’t have a meticulously well formed plan for this time-waster ( <- for you, heh, heh) in my fallible cranium and I made many mid-course corrections as I crab-walked like a drunken sailor toward the finish line. Hell, I didn’t even know where the freakin’ finish line was. I stopped iteratively writing/drawing when I subjectively concluded that….. tada, “I’ve arrived!”. Such is the nature of exploration, discovery, and exposition, no? If you disagree, why?

Pristine Profile – Full Steam Ahead!

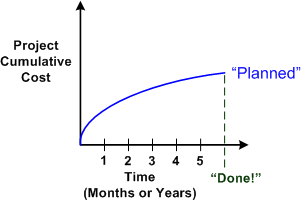

The figure below shows the shape of a pristine, planned, cost vs time profile at “project start” for a long term, resource-intensive, project to do something “big and grand for the world”. Some one or some group has consulted their crystal ball and concocted a cost vs schedule curve based on vague, subjective criteria, and bolstered by a set of ridiculously optimistic assumptions and a bogus risk register “required for signoff“. To coverup the impending calamity, the schedule has been enunciated to the troops as “aggressive“. BTW, have you ever heard of a non-aggressively scheduled big project?

It’s interesting to note that the dudes/dudettes who “craft” cost profiles for big quagmire projects are never the ones who’ll roll up their sleeves, get dirty, and actually do the downstream work. Even if the esteemed planners are smart enough to actually humbly ask for estimates from those who will do the work, they automatically chop them down to size based on whim, fancy, and political correctness. <- LOL!

Typical Profile – Bummer

The figure below shows (in hindsight) the actual vs planned cost curve for a hypothetical “bummer” project. The project started out overestimated (yes, I actually said overestimated), and then, as the cost encroached into uncomfortable territory, the plan became, uh, optimistic. Since it was underestimated for “political reasons” (what other reason is there?), but no one had a clue as to whether the plan was sane, no acknowledgement of the mistake was made during the entire execution and no replanning was done. The loss accumulated and accumulated until end game – whatever that means.

Crisis Profile – We’re Vucked!

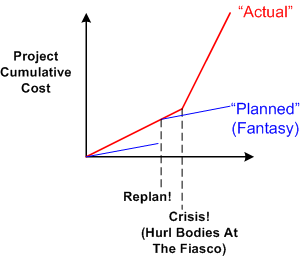

The figure below shows (in hindsight) the actual vs planned cost curve for a hypothetical “vucked” project. Cost-wise, the project started out OK, but because it was discovered that technical progress wasn’t really, uh, technical progress, bodies were thrown onto the bonfire. Again, the financial loss accumulated and accumulated until end game – whatever that means.

Replan Profile – Fantasy Revisited

The figure below shows (in hindsight) the actual vs planned cost curve for a hypothetical “fantasy revisited” project. Cost-wise, the project started out OK (snore, snore, Zzzzz), but because it was discovered that technical progress wasn’t really, uh, technical progress, bodies were thrown on the bonfire. But his time, someone with a conscience actually fessed up (yeah, some people are like that, believe it or not) and the project was replanned in real-time, during execution. Alas, this is not Hollywood and the financial loss accumulated and accumulated until end game – whatever that means.

Iterative, Incremental Profile – No Freakin’ Way

Alright, alright. As everyone knows, and this especially includes you, it’s easy to rag about everyone and everything – “everything sux and everyone’s an a-hole; blah, blah, blah…. aargh!”. What about an alternative, Mr. Smarty Pants? Even though I have no idea if it’ll work, try this one on for size (and it’s definitely not original).

The figure below shows (in hindsight) the actual vs planned cost curve for a hypothetical “no freakin’ way” project. But wait a minute, you cry. There’s only one curve! Shouldn’t there be two curves you freakin’ bozeltine? There’s only one because the actual IS the planned. This can be the case because if the planning increments are small enough, they can almost equate to the actual expenditures. At each release and re-evaluation point, the real thing, which is the product or service that is being provided (product and service are unknown concepts to bureaucrats and executive fatheads), is both objectively and subjectively evaluated by the people who will be using the damn thing in the future. If they say “This thing sux!”, its fini, kaput, end game before scheduled end game. If they say “Good job so far! I can envision this thing helping me do my job better with a few tweaks and these added features”, then it’s onward. The chances are high that with this type of rapid and dynamic learning SCRBF system in place, projects that should be killed will be killed, and projects that should continue will continue. Agree, or disagree? What say you?

This hypothetical project is called “No Freakin’ Way” because there is “no freakin’ way” that the system of co-dependent failure designed and kept in place by hierarchs in both contractor and contractee institutions will ever embrace it. What do you think?

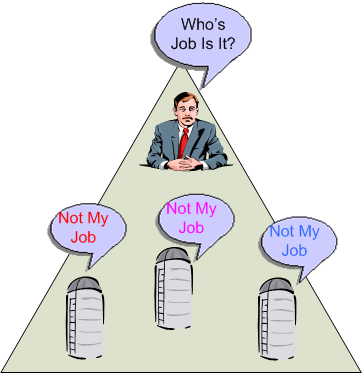

Supported By, Not Partitioned Among

“A design flows from a chief designer, supported by a design team, not partitioned among one.” – Fred Brooks

partitioning == silos == fragmented scopes of responsibility == it’s someone else’s job == uncontrolled increase in entropy == a mess == pissed off customers == pissed off managers == disengaged workers

“Who advocates … for the product itself—its conceptual integrity, its efficiency, its economy, its robustness? Often, no one.” – Fred Brooks

Note for non-programmers: “==” is the C++ programming language’s logical equality operator. If the operator’s left operand equates to its right operand, then the expression is true. For example, the expression “1 == 1” (hopefully) evaluates to true.

Knowing this, do you think the compound expression sandwiched between the two Brooks’s quotes evaluates to true? If not, where does the chain break?

The Best Defense

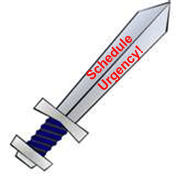

In “The Design Of Design“, Fred Brooks states:

The best defense against requirements creep is schedule urgency.

Unfortunately, “schedule urgency” is also the best defense against building a high quality and enduring system. Corners get cut, algorithm vetting is skipped, in-situ documentation is eschewed, alternative designs aren’t investigated, and mistakes get conveniently overlooked.

Yes, “schedule urgency” is indeed a powerful weapon. Wield it carefully, lest you impale yourself.

Leverage Point

In this terrific systems article pointed out to me by Byron Davies, Donella Meadows states:

Physical structure is crucial in a system, but the leverage point is in proper design in the first place. After the structure is built, the leverage is in understanding its limitations and bottlenecks and refraining from fluctuations or expansions that strain its capacity.

The first sentence doesn’t tell me anything new, but the second one does. Many systems, especially big software systems foisted upon maintenance teams after they’re hatched to the customer, are not thoroughly understood by many, if any, of the original members of the development team. Upon release, the system “works” (and it may be stable). Hurray!

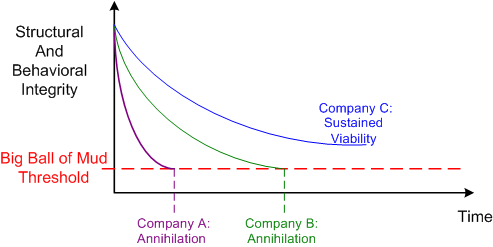

In the post delivery phase, as the (always) unheralded maintenance team starts adding new features without understanding the system’s limitations and bottlenecks, the structural and behavioral integrity of the beast starts surely degrading over time. Scarily, the rate of degradation is not constant; it’s more akin to an exponential trajectory. It doesn’t matter how pristine the original design is, it will undoubtedly start it’s march toward becoming an unlovable “big ball of mud“.

So, how can one slow the rate of degradation in the integrity of a big system that will continuously be modified throughout its future lifetime? The answer is nothing profound and doesn’t require highly skilled specialists or consultants. It’s called PAYGO.

In the PAYGO process, a set of lightweight but understandable and useful multi-level information artifacts that record the essence of the system are developed and co-evolved with the system software. They must be lightweight so that they are easily constructable, navigable, and accessible. They must be useful or post-delivery builders won’t employ them as guidance and they’ll plow ahead without understanding the global ramifications of their local changes. They must be multi-level so that different stakeholder group types, not just builders, can understand them. They must be co-evolved so that they stay in synch with the real system and they don’t devolve into an incorrect and useless heap of misguidance. Challenging, no?

Of course, if builders, and especially front line managers, don’t know how to, or don’t care to, follow a PAYGO-like process, then they deserve what they get. D’oh!

Perverted Inversion

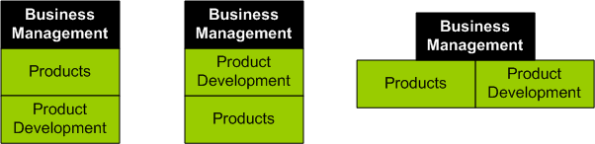

In simplistic terms, material wealth in the form of profits is created through the delivery of products and/or services that provide some sort of perceived value to a set of customers. The figure below illustrates the priorities, from highest on the top to lowest on the bottom, of all successful product-oriented startup businesses.

Since products create the wealth that sustains a business, they receive top billing. The care and feeding of the golden geese via a supportive product development group is next in importance. At the bottom, and deservedly so, is the management of the business. Nevertheless, the fact that it’s on the priority list at all means that managing the business is important – but not as important as the product-centric activities.

Without any facts or any background research to back it up (cuz I like to make stuff up), I assert that most entrepreneurs hate doing the business management “stuff”. Some despise the mundane activities of running a business so much that their negligence can cause the fledgling enterprise to fail just as quick as launching the business without any product or service to sell. Having said that, hopefully you’ll agree that any business priority list without the product portfolio perched at the top is a sure path to annihilation. The other two arrangements of the lower priority activities (shown below) can also work, but maybe not as effectively as the initial proposed stack.

As a business thrives and grows larger, a strange perverted inversion occurs to those who lose their way (but thankfully, not all do). The business management function bubbles to the surface of the priority stack (WTF?). This happens ubiquitously across the land because hot shot, fat headed, generic managers who don’t know squat about the org’s specific product portfolio are chaufeurred in to grow the business. These immodest dudes, thinking of themselves as Godsends from MBA city, put themselves and what they do at the top of the priority stack to…… enrich themselves no matter what. Of course, these wall street stooges perform this magic act while espousing that the product set and those that create it are forever the org’s “most valuable asset“.

Post-startup businesses can survive with the perverted priority stack in place, but they usually muddle along with the rest of the herd and they aren’t exhilarating or engaging places to work. Do you work for one?

At a certain age institutional minds close up; they live on their intellectual fat. – William Lyon Phelps

Meta-test Tools

A meta test tool ties together other lower level workhorse test tools in one place. Users interface with a meta test tool to launch and control the underlying system tool set that exercises the system under test. However, if you don’t have any low level test tools (out of dumbass neglect or innocent ignorance), a meta test tool is useless. But hey, the user interface and the camouflage it generates look good.

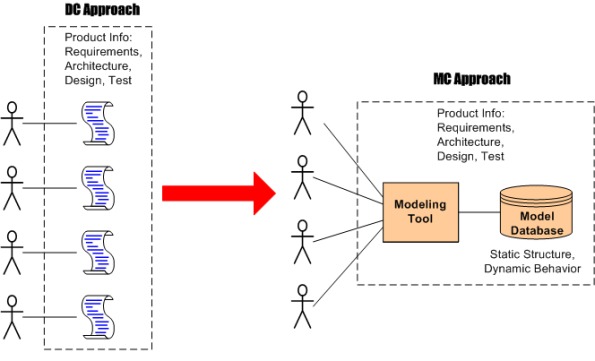

Docu-centric, Model-centric

Let’s say that your org has been developing products using a Docu-Centric (DC) approach for many years. Let’s also say that the passage of time and the experience of industry peers have proven that a Model-Centric (MC) mode of development is superior. By superior, I mean that MC developed products are created more quickly and with higher quality than DC developed products.

Now, assume that your org is heavily invested in the old DC way – the DC mindset is woven into the fabric of the org. Of course, your bazillions of (probably ineffective) corpo processes are all written and continuously being “improved” to require boatloads of manually generated, heavyweight documents that clearly and unassailably prove that you know what you’re doing (lol!) to internal and external auditors.

How would you move your org from a DC mindset to an MC mindset? Would you even risk trying to do it?

Short Cycle, Long Cycle

Since my memory isn’t that great, I think (but am not sure) that I wrote about short and long cycle run-break-fix before. Nevertheless, I’m gonna do it again because repetition can drive a message home.

In a nutshell, short cycle run-break-fix (SCRBF) and LCRBF are ways of enhancing product quality. High frequency SCRBF iteration jacks up quality by removing errors and fixing design disasters before a product gets shipped to customers. LCRBF is (hopefully) a low frequency technique of error removal after a product has made it into the customer’s hands. In that sense, SCRBF is good and LCRBF is bad. In a perfect world, LCRBF is never needed because the customer gets exactly what he/she wants right out of the shoot.

The figure below depicts side-by-side models of two different company’s day to day operating systems. Which one do you think is more successful? Why do you think the company on the right doesn’t do any SCRBF? Could it be that internal mistakes aren’t tolerated and hence covered up? Do you think it’s innocent ignorance? Do you think it’s because management puts schedule first and quality second – while publicly espousing the opposite? Which model best represents your company’s ingrained way of doing things?

Note: The terms SCRBF and LCRBF were coined by William L. Livingston in his masterful second book, “Have fun at work“.

Buffer Gone Awry

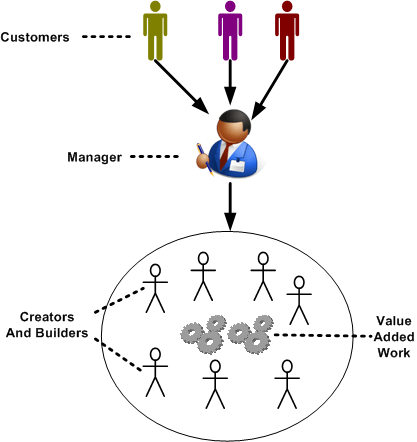

Assume that you’re a manager enveloped within the predicament below. On a daily basis, you’re trying to coordinate bug fixes and new feature additions to your product while simultaneously getting hammered by internal and external customers with problem reports and new feature requests.

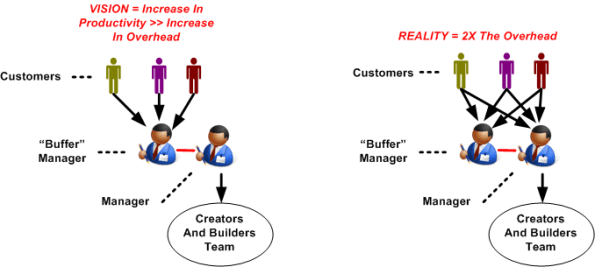

In order to reduce your workload and increase productivity, your meta-manager decides to add a “buffer” manager to filter and smooth out the customer interface side of your job. As the left side of the figure below shows, the hope is that the team’s increased productivity will offset the doubling of overhead costs associated with adding a second manager to the mix. However, when your customers find out that they now have two managers to voice their problems and needs to, the situation on the right develops: your workload remains the same; you now have an additional interface with the buffer manager (who has less of a workload than you); the overhead cost to the org doubles. Bummer.

Iteration Frequency

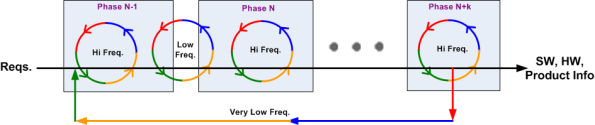

Obviously, even the most iterative agile development process marches forward in time. Thus, at least to a small extent, every process exhibits some properties of the classic and much maligned waterfall metaphor. On big projects, the schedule is necessarily partitioned into sequential time phases. The figure below (Reqs. = requirements, Freq. = frequency, HW = hardware, SW = software) attempts to model both forward progress and iteration as a function of time.

If the phases are designed to be internally cohesive, externally loosely coupled , and the project is managed correctly, the frequency of iteration triggered by the natural process of human learning and fixing mistakes is:

- high within a given project phase

- low between adjacent project phases

- very low between non-adjacent project phases

Of course, if managed stupidly by explicitly or implicitly “disallowing” any iterative learning loops in order to meet equally stupid and “aggressive” schedules handed down from the heavens, errors and mistakes will accumulate and weave themselves undetected into the product fabric – until the customer starts using the contraption. D’oh!