Archive

Bugs Or Cash

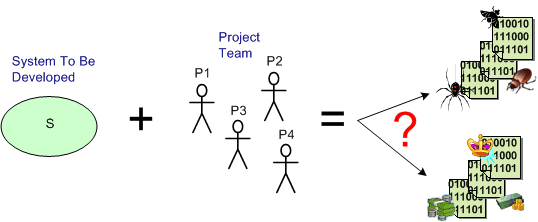

Assume that you have a system to build and a qualified team available to do the job. How can you increase the chance that you’ll build an elegant and durable money maker and not a money sink that may put you out of business.

The figure below shows one way to fail. It’s the well worn and oft repeated ready-fire-aim strategy. You blast the team at the project and hope for the best via the buzz phrase of the day – “emergent design“.

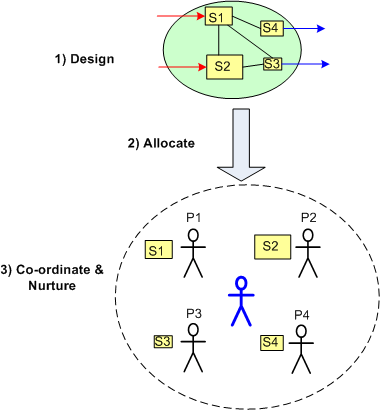

On the other hand, the figure below shows a necessary but not sufficient approach to success: design-allocate-coordinate. BTW, the blue stick dude at the center, not the top, of the project is you.

On the other hand, the figure below shows a necessary but not sufficient approach to success: design-allocate-coordinate. BTW, the blue stick dude at the center, not the top, of the project is you.

Where Elitism Is Proper?

Ever since I stumbled upon Fred Brooks‘s meta-physical idea of “Conceptual Integrity” in his classic book, “The Mythical Man Month“, I’ve strived mightily to achieve that elusive quality in the software work that I do. Over twenty years ago, Mr. Brooks stated that the greatest conceptually integral designs were the product of one, or at most two, human minds. Fred asserts that his “one or two minds” principle still holds true today:

My fictional alter ego, Bulldozer aught aught, would’ve re-worded the beginning of the statement to “Most, if not all… “, but Fred’s message stills rings loud and true.

According to Fred, in today’s world of exponentially growing complexity and team sizes, conceptual integrity is more difficult to achieve than ever:

Why the increased difficulty? Because as a team grows larger, more minds will collide with each other to express and manifest their incompatible design ideas. Big projects can, and usually do, devolve into “design by committee” fiascos where monstrously over-complicated contraptions get created and foisted upon the world.

Ok, Ok, you say. Enough disclosure of the pervasive problem – we get it Yoda. What’s the solution, bozo? Here it is:

Even though it sounds simple to enact this policy, it’s not. The role of “Chief Designer” in a group of highly educated, independent thinking people is fraught with peril. It requires a dose of discipline imposition that can be perceived as “meanness” to external observers. Too much perceived meanness can cause a supporting team to morph into an unsupporting team and lead to the ejection and ostracism of the chief designer. Too little meanness and the possibility of achieving conceptual integrity goes right out the window – it’s Rube Goldberg city. Bummer.

Even though it sounds simple to enact this policy, it’s not. The role of “Chief Designer” in a group of highly educated, independent thinking people is fraught with peril. It requires a dose of discipline imposition that can be perceived as “meanness” to external observers. Too much perceived meanness can cause a supporting team to morph into an unsupporting team and lead to the ejection and ostracism of the chief designer. Too little meanness and the possibility of achieving conceptual integrity goes right out the window – it’s Rube Goldberg city. Bummer.

Does your org explicitly recognize and implement the “Chief Designer” role – which is not the same as the softer, less technical, more politically correct, and more administrative “software lead”, “project manager”, “product manager”, and…….. “software rocket-tect” roles? If your org does formally implement the “Chief Designer” role, are your chief designers kept on a tight leash by higher ranking BUTTS, BMs, BOOGLs, SCOLs or CGHs that have no idea what “conceptual integrity” means? Worse, do your “Chief Designers” (again, if you have any) handcuff themselves in order to increase their promotability?

I’m not into corpo caste systems or stratified command-control hierarchies and I struggle endlessly to fight the instinct to play the “I’m smarter than you” game, but I agree with Mr. Brooks when he asserts that world class product design is one of those rare situations…..

How about you? Where do you stand…… or sit?

How about you? Where do you stand…… or sit?

Note: The snippets in this blarticle were copied and pasted from Fred Brooks’s “The Design Of Design” pitch at the Construx Software Executive Summit. You can download and study it in its entirety from here: Summit Materials.

From Wanted To Unwanted

You can have a product without a business, but you can’t have a business without a product. If you build a product that people want, a business will be born either from your loins or from some copycat’s. There’s no chicken and egg dilemma here. It’s simply, product-first and business-second. Ka-ching!

But wait, that’s not all! Let’s say you do get lucky and start a biniss around a “wanted” product that you built. To sustain your business, you gotta sustain your product. That means continuously maintaining it via the addition of new value-added features and the correction of customer-annoying defects.

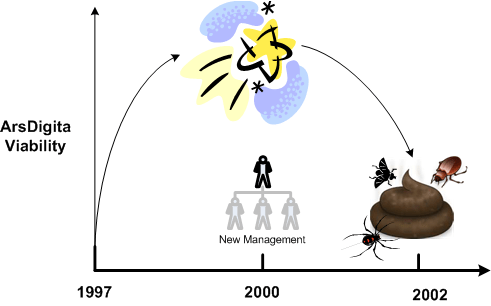

Upon observing the deterioration of his original ArsDigita product under the so-called leadership of “new management”, Philip Greenspun said:

Once you have a product that nobody wants, it doesn’t matter how good your management team is. – Phil Greenspun (Founders At Work, Jessica Livingston)

So, how does a “wanted” product morph into an “unwanted” product? Via neglect and indifference. That’s what happened to Phil’s baby when the vulture capitalists he hooked up with installed an incompetent “professional management team” to run ArsDigita (into the ground). By focusing on the superficial instead of the substance, the promotion instead of the maintenance, the company’s product, and then the company itself, went down hill fast:

ArsDigita grew out of the software that Greenspun wrote for managing photo.net, a popular photography site. He released the software under an open source license and was soon deluged by requests from big companies for custom features. He and some friends founded ArsDigita in 1997 to take on such consulting projects. In 2000, ArsDigita took $38 million from venture capitalists. Within weeks of the deal closing, conflict arose between the new investors and the founders. They marginalized and then fired most of the founders, who responded by retaking control of the company using a loophole the VCs had overlooked. The legal battle culminated in Greenspun’s being bought out, and a few months later the company crashed. ArsDigita was dissolved in 2002. – (Founders At Work, Jessica Livingston)

Zero Time, Zero Cost

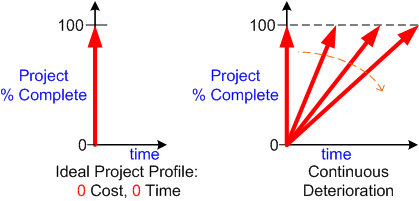

In “The Politics Of Projects“, Robert Block states that orgs “don’t want projects, they want products“. Thus, the left side of the graph below shows the ideal project profile; zero cost and zero time. A twitch of Samantha Stevens’s nose and, voila, a marketable product appears out of thin air and the revenue stream starts flowin’ into the corpo coffers.

Based on a first order linear approximation, all earthly product development orgs get one of the performance lines on the right side of the figure. There are so many variables involved in the messy and chaotic process from viable idea to product that it’s often a crap shoot at predicting the slope and time-to-100-percent-complete end point of the performance line:

- Experience of the project team

- Cohesiveness of the project team

- Enthusiasm of the project team

- Clarity of roles and responsibilities of each team member

- Expertise in the product application domain

- Efficacy of the development tool set

- Quality of information available to, and exchanged between, project members

- Amount and frequency of meddling from external, non-project groups and individuals

- <Add your own performance influencing variable here>

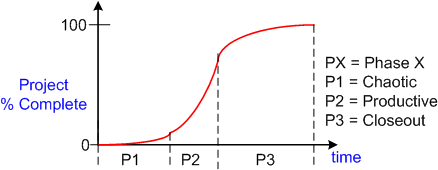

To a second order approximation, the S-curve below shows real world project performance as a function of time. The slope of the performance trajectory (% progress per unit time) is not constant as the previous first order linear model implies. It starts out small during the chaotic phase, increases during the productive stage, then decreases during the closeout phase. The objective is to minimize the time spent in phases P1, P2, and P3 without sacrificing quality or burning out the project team via overwork.

Assume (and it’s a bad assumption) that there’s an objective and accurate way of measuring “% complete” at any given time for a project. Now, assume that you’ve diligently tracked and accumulated a set of performance curves for a variety of large and small projects and a variety of teams over the years. Armed with this data and given a new project with a specific assigned team, do you think you could accurately estimate the time-to-completion of the new project? Why or why not?

Assume (and it’s a bad assumption) that there’s an objective and accurate way of measuring “% complete” at any given time for a project. Now, assume that you’ve diligently tracked and accumulated a set of performance curves for a variety of large and small projects and a variety of teams over the years. Armed with this data and given a new project with a specific assigned team, do you think you could accurately estimate the time-to-completion of the new project? Why or why not?

Innovation Types

In the beginning of Scott Berkun’s delightful and entertaining “Managing Breakthrough Projects” video, Scott talks about two supposed types of innovation: product and process. He (rightly) poo-pooze away process innovation as not being innovative at all. Remember the business process re-engineering craze of the 90’s, anyone? Sick-sigma? Oh, I forgot that sick-sigma works. So, I’m sorry if I offended all you esteemed, variously colored belt holders out there.

According to self-professed process innovators, the process innovations they conjure up reduce the time and/or cost of making a product or performing a service without, and here’s the rub, sacrificing quality. Actually, most of the process improvement gurus that I’ve been exposed to don’t ever mention the word “quality”. They promise to reduce time to market (via some newfangled glorious tool or methodology) or cost (via, duh, outsourcing). Some of these snake oil salesmen dudes actually profess that they can increase quality while decreasing time and cost.

The difference between a terrorist and a methodologist is that you can negotiate with a terrorist – Unknown

Most process improvement initiatives that I’ve been, uh, lucky(?) to be a part of didn’t improve anything. That’s because the “improvements” weren’t developed by those closest to the work. You know, those interchangeable, fungible people who actually understand what processes and methods need to be done to ensure high quality.All that those highly esteemed, title-holding, mini-Hitlers did was saddle the value makers and service providers down with extra steps and paperwork and impressive looking checklists that took away productive time formerly used to make products and provide services.

Process improvement is a high-minded, overblown way of saying “kill the goose that laid the golden egg before it lays another one“.

PAYGO II

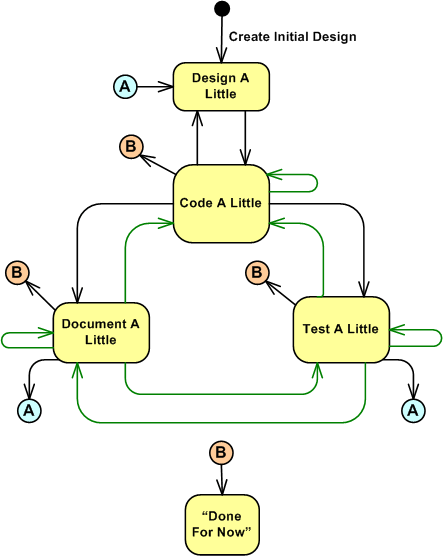

PAYGO stands for “Pay As You Go“. It’s the name of the personal process that I use to create or maintain software. There are five operational states in PAYGO:

- Design A Little

- Code A Little

- Test A Little

- Document A Little

- Done For Now

Yes, the fourth state is called “Document A Little“, and it’s a first class citizen in the PAYGO process. Whatever process you use, if some sort of documentation activity is not an integral part of it, then you might be an incomplete and one dimensional engineer, no?

“…documentation is a love letter that you write to your future self.” – Damian Conway

The UML state transition diagram below models the PAYGO states of operation along with the transitions between them. Even though the diagram indicates that the initial entry into the cyclical and iterative PAYGO process lands on the “Design A Little” state of activity, any state can be the point of entry into the process. Once you’re immersed in the process, you don’t kick out into the “Done For Now” state until your first successful product handoff occurs. Here, successful means that the receiver of your work, be it an end user or a tester or another programmer, is happy with the result. How do you know when that is the case? Simply ask the receiver.

Notice the plethora of transition arcs in the diagram (the green ones are intended to annotate feedback learning loops as opposed to sequential forward movements). Any state can transition into any other state and there is no fixed, well defined set of conditions that need to be satisfied before making any state-to-state leap. The process is fully under your control and you freely choose to move from state to state as “God” (for lack of a better word) uses you as an instrument of creation. If clueless STSJ PWCE BMs issue mindless commands from on high like “pens down” and “no more bug fixing, you’re only allowed to write new code“, you fake it as best you can to avoid punishment and you go where your spirit takes you. If you get caught faking it and get fired, then uh….. soothe your conscience by blaming me.

The following quote in “The C++ Programming Language” by mentor-from-afar Bjarne Stroustrup triggered this blog post:

In the early years, there was no C++ paper design; design, documentation, and implementation went on simultaneously. There was no “C++ project” either, or a “C++ design committee.” Throughout, C++ evolved to cope with problems encountered by users and as a result of discussions between my friends, my colleagues, and me. – Bjarne Stroustrup

When I read it on my Nth excursion through the book (you’ve made multiple trips through the BS book too, no?), it occurred to me that my man Bjarne uses PAYGO too.

Say STFU to all the mindlessly mechanistic processes from highly-credentialed and well-intentioned luminaries like Watts Humphrey’s PSP (because he wants to transform you into an accountant) and your mandated committee corpo process group (because the chances are that the dudes who wrote the process manuals haven’t written software in decades) and the TDD know-it-alls. Embrace what you discover is the best personal development process for you; be it PAYGO or whatever personal process the universe compels you to embrace. Out of curiosity, what process do you use?

If you’re interested in a higher level overview of the personal PAYGO process in the context of other development processes, you can check out this previous post: PAYGO I. And thanks for listening.

The Meeting Surrogate

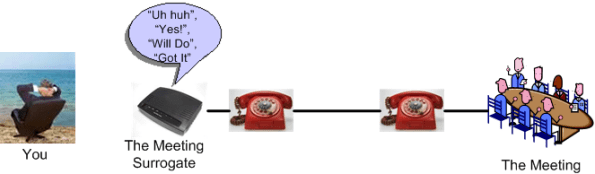

How’s this for a new product idea, “The Meeting Surrogate“. It’s a gadget that hooks up to your phone and participates in call-in conference meetings for you – freeing you up to do whatever you’d like. When you power it on and press its “Start BS” button, it intelligently monitors the conversations and strategically voices out words and phrases like “uh huh”, “yes – yes”, “I get it”, “very insightful”, “nice”, “understood”, “got it”, at appropriate times during the yawnfest.

“The Meeting Surrogate” is extendable. You could program in catchy new phrases as you think of them when you’re offline. You pre-configure “The Meeting Surrogate” by speaking into it so that it can process and store a replica of the pitch, tone, and inflections of your voice.

Do ya think it would sell to the Dilbert crowd? How much should it cost?

Meetings are a refuge from the dreariness of labor and the loneliness of thinking – Bernard Barush

It’s Gotta Be Free!

I love ironies because they make me laugh.

I find it ironic that some software companies will staunchly avoid paying a cent for software components that can drastically lower maintenance costs, but be willing to charge their customers as much as they can get for the application software they produce.

When it comes to development tools and (especially) infrastructure components that directly bind with their application code, everything’s gotta be free! If it’s not, they’ll do one of two things:

- They’ll “roll their own” component/layer even though they have no expertise in the component domain that cries out for the work of specialized experts. In the old days it was device drivers and operating systems. Today, it’s entire layers like distributed messaging systems and database managers.

- They’ll download and jam-fit a crappy, unpolished, sporadically active, open source equivalent into their product – even if a high quality, battle-tested commercial component is available.

Like most things in life, cost is relative, right? If a component costs $100K, the misers will cry out “holy crap, we can’t waste that money“. However, when you look at it as costing less than one programmer year, the situation looks different, no?

How about you? Does this happen, or has it happened in your company?

Ya Gotta Use This!

It’s interesting when people come off a previous project and are assigned to a new, in-progress, software development project. Often, they demand that their new project team adopt a process/procedure/technique/design/architecture (PPTDA) that they themself used on their previous project.

This can be either good or bad. It can be good if (and it’s a big IF) the alternative PPTDA they are promoting is actually better than the analogous PPTDA currently being employed by the new project team and the cost to integrate the proposed PPTDA into the project environment is less than the additional benefit it brings to the table. It can be really good if the PPTDA has been proven to “work” well and the new project hasn’t progressed past the point where an analogous PPTDA has been decided upon and weaved into the fabric of the project.

On the other hand, a newly proposed PPTDA can be bad in these cases:

- The new project team already has an equivalent PPTDA in place and there’s no “objective” proof that the championed PPTDA really does work better.

- The new project team already has an equivalent PPTDA in place and there’s “objective” proof that the championed PPTDA really does work better, but the cost of social disruption to integrate the PPTDA into the project isn’t worth the benefit.

- The new project team doesn’t have an equivalent PPTDA in place yet and the championed PPTDA has “somehow” been proven to be better than other alternatives, but adopting it would require changes to other well-working PPTDAs that the team is using.

Because there’s a bit of subjectivity in the above list and “rank can be pulled” by a so-called superior in order to jam an unworthy PPTDA into a smoothly running project and muck up the works, be wary of kings bearing gifts.

Armed And Ready

How much technical acumen does a project manager need to have in order to effectively manage a software-intensive product development effort? Are Spreadsheet, Gannt chart, PERT chart, EVM, Microsoft Project skills, and a golden certificate from schools like the vaunted PMI the only tools needed to lead a multi-disciplined, technical crew of engineers to so-called victory? I think not, but you may think differently – especially (and understandably) if you’re a project/program manager.

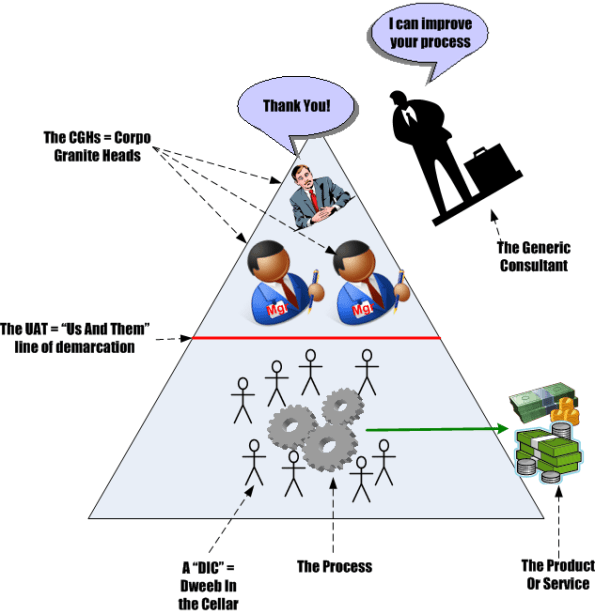

I think effective technical project managers are rare and they sprout from the trenches of one or more of the technical disciplines: software, hardware, test, and systems engineering. Wrestling with technical problems in the mud while under schedule pressure from multiple managers to keep costs down and to deliver quality promptly is the hazing experience needed to appreciate both the financial and technical aspects of a project or program. It may seem that project and program managers are under pressure themselves from executives above them in the command and control hierarchy, but unlike the dudes at the bottom of the food chain, they can easily pass the buck when financial and technical goals aren’t met. Who do ineffective BMs pass the buck to when the execs in the heavens demand accountability for poor project performance (usually way downstream after project execution has been supposedly progressing splendidly)? Why, the dweebs in the cellar of course.

“You have to know a lot to be of help. It’s slow and tedious. You don’t have to know much to cause harm. It’s fast and instinctive.” – Rudolph Starkermann

Cranking fat heads off the project management education assembly line and arming them with the necessary but insufficient skills to lead technically smart people into the raging battle against complexity is like arming firefighters with squirt guns to put out a 5 alarm fire. All it does is perpetuate the illusion of control and prep the graduates for moving higher up on the Plan-Watch-Control-Evaluate ladder – even though they don’t have a clue as to what they’ll be planning-watching-controlling-evaluating. But hey, I like to make things up and I’m not fit to lead anything, so don’t listen to a word I say 🙂