Archive

Just As Fast, But Easier To Write

I love watching Herb Sutter videos on C++. His passion and enthusiasm for the language is infectious. Like Scott Meyers, Herb always explains the “why” and “how” of a language feature in addition to the academically dry “what” .

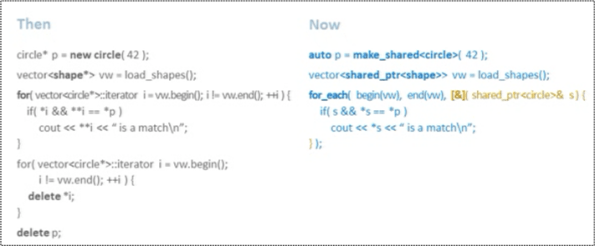

In this talk, “Writing modern C++ code: how C++ has evolved over the years“, Herb exhibits several side by side code snippets that clearly show much easier it is to write code in C++11 (relative to C++98) without sacrificing efficiency.

Here’s an example (which I hope isn’t too blurry) in which the C++11 code is shorter and obsoletes the need for writing an infamous”new/delete” pair.

Note how Herb uses the new auto, std::make_shared, std::shared_ptr, and anonymous lambda function features of C++11 to shorten the code and minimize the chance of making mistakes. In addition, Herb’s benchmarking tests showed that the C++11 code is actually faster than the C++98 equivalent. I don’t know about you, but I think this is pretty w00t!

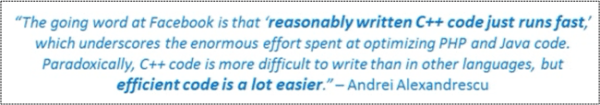

I love paradoxes because they twist the logical mind into submission to the cosmos. Thus, I’m gonna leave you with this applicable quote (snipped from Herb’s presentation) by C++ expert and D language co-creator Andrei Alexandrescu:

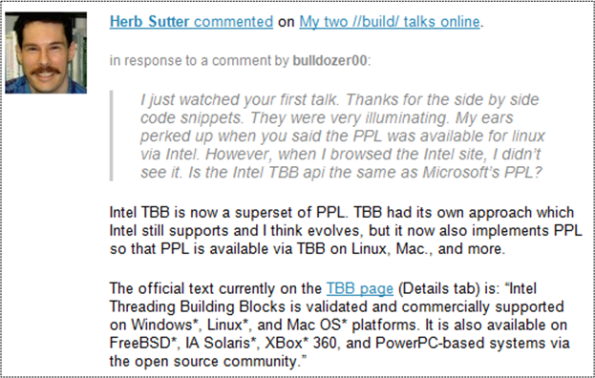

Note: As a side bonus of watching the video, I found out that the Microsoft Parallel Patterns Library is now available for Linux (via Intel).

Sanity, Stability, Insanity, Instability

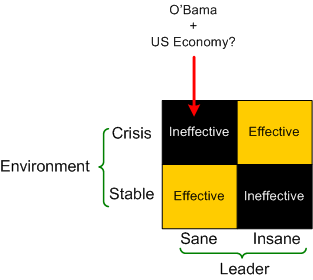

Because of the seemingly outrageous premises upon which the book is based, I found Nassir Ghaemi’s “A First-Rate Madness: Uncovering the Links Between Leadership and Mental Illness” fascinating. Mr. Ghaemi asserts that mentally healthy leaders do a great job in times of stability, but they fail miserably in times of crisis due to something akin to acquired “hubris syndrome“. On the flip side, he asserts that mentally unhealthy leaders, being more empathic ans less susceptible to hubris syndrome, are effective in times of crisis, but woefully ineffective in stable times.

What follows is the impressive list of leaders Mr. Ghaemi “analyzes” to promote his view. First, the wackos: William Tecumseh Sherman, Ted Turner, Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy. Next, the sane dudes: Richard Nixon, George McClellan, Neville Chamberlain, George W. Bush, and Tony Blair. He also “delicately” addresses where Adolph Hitler fits into his scheme of things.

Here are several passages that I highlighted on my Kindle and shared on Twitter:

We are left with a dilemma. Mental health—sanity—does not ensure good leadership; in fact, it often entails the reverse. Mental illness can produce great leaders, but if the illness is too severe, or treated with the wrong drugs, it produces failure or, sometimes, evil. The relationship between mental illness and leadership turns out to be quite complex, but it certainly isn’t consistent with the common assumption that sanity is good, and insanity bad.

Depression makes leaders more realistic and empathic, and mania makes them more creative and resilient. Depression can occur by itself, and can provide some of these benefits. When it occurs along with mania—bipolar disorder—even more leadership skills can ensue. A key aspect of mania is the liberation of one’s thought processes.

Creativity may have to do less with solving problems than with finding the right problems to solve. Creative scientists sometimes discover problems that others never realized. Their solutions aren’t as novel as is their recognition that those problems existed to begin with.

In a strong economy, the ideal business leader is the corporate type, the man who makes the trains run on time, the organizational leader. He may not be particularly creative, but he doesn’t need new ideas; he only needs to keep going what’s going. Arthur Koestler called this kind of executive the Commissar; much as a Soviet bureaucrat administers the state, the corporate executive administers the company. This is not a minor matter; administration is no easy task; but with this approach, all is well only when all that matters is administration.

When the economy is in crisis, when profits have fallen, when consumers no longer demand one’s goods or competitors produce better ones, then the Commissar fails; the corporate executive takes a backseat to the entrepreneur, whom Koestler called the Yogi. This is the crisis leader, the creative businessman who either produces new ideas that navigate the old company through changing times or, more often, produces new companies to meet changing needs.

Yet absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Like Gandhi, King tried to commit suicide as a teenager; in fact, King made two attempts. It is surprising how little this fact is recalled.

Many people fear nothing more terribly than to take a position which stands out sharply and clearly from prevailing opinion. The tendency of most is to adopt a view that is so ambiguous that it will include everything and so popular that it will include everybody. . . . The saving of our world from pending doom will come, not through the complacent adjustment of the conforming majority, but through the creative maladjustment of a nonconforming minority.

Mentally healthy leaders like George W. Bush make decisions, but refuse to modify them when they do not work well.

Still, given the challenges, some might well ask: Why take the risk? Why not just exclude the mentally ill from positions of power? As we’ve seen, such a stance would have deprived humanity of Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Kennedy. But there’s an even more fundamental reason not to restrict leadership roles to the mentally healthy: they make bad leaders in times of crisis—just when we need good leadership most.

Most of us think and act similarly. Most people have a hard time admitting error, apologizing, changing our minds. It takes more than a typical amount of self-awareness to realize that one is wrong and to admit it.

“Proud mediocrity” resists the notion that what is common, and thus normal, may not be best.

Regardless of whether you agree with his analyses and conclusions after you’re done reading the book, I think you’ll have enjoyed the reading experience.”

Movement And Progress

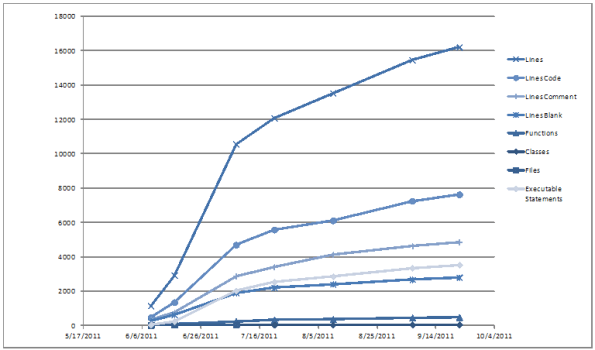

In collaboration with a colleague, I’m currently designing, writing, and testing a multi-threaded, soft-real-time application component for a distributed, embedded sensor system. The graph below shows several metrics that characterize our creation.

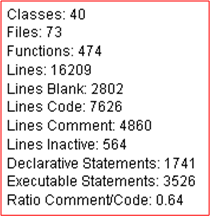

The numbers associated with the most recent 9/22/11 time point are:

Of course, the pretty graph and its associated “numbers” don’t give any clue as to the usefulness or stability of our component, but “movement” is progressing forward. Err, is it?

Don’t confuse movement with progress – Tom Peters

What’s your current status?

Illusion, Not Amplification

The job of the product development team is to engineer the illusion of simplicity, not to amplify the perception of complexity.

Software guru Grady Booch said the first part of this quote, but BD00 added the tail end. Apple Inc.’s product development org is the best example I can think of for the Booch part of the quote, and the zillions of mediocre orgs “out there” are a testament to the BD00 part.

According to Warren Buffet, the situation is even worse:

There seems to be some perverse human characteristic that likes to make easy things difficult. – Warren Buffet

Translated to BD00-lingo:

Engineers like to make make easy things difficult, and difficult things incomprehensible.

Why do they do it? Because:

A lot of people mistake unnecessary complexity for sophistication. – Dan Ward

Conclusion:

The quickest routes to financial ruin are: wine, women, gambling….. and engineers

Confined Safety

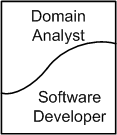

In ho-hum, yawner borgs, a meticulously followed but mysteriously unwritten rule is that Domain Analysts (DA) and Software Developers (SD) remain safely within the confines of their area of expertise:

The borg’s job classification, compensation, and status-award sub-systems ensure that this “confined safety” rule is firmly in place; and silently enforced. No encroachment is allowed, lest social punishment be inflicted to “right the wrong“.

When turf transgressions in the form of hard-to-answer questions and “suggested” alternatives from an encroacher occur:

a rebuke from the (Jim) encroachee is sure to follow. If that tactic doesn’t flatten and widen the boundary curve back into place, then the big gun is rolled out: management. D’oh! Watchout!

In effective, world class orgs, there is no “confined safety” rule:

This non-horizontal, continuous, and smooth interface boundary between disciplines is not only an anomaly, but when it does miraculously manifest, it’s only temporary and local, no?

Hell, there are no rules here. We’re trying to accomplish something. – Thomas Alva Edison

Ubiquitous Dishonorability

While reading the delightful “Object-Oriented Analysis and Design with Applications“, Grady Booch et al extol the virtues of object-oriented analysis over the venerable, but passe, structured analysis approach to front end system composition. As they assert below, one of the benefits of OOA is that it’s easier and more natural to avoid mixing concrete design details with abstract analysis results.

Out of curiosity (which killed the cat), I scrolled down to see what note [4] meant:

WTF? Do they mean “because that’s the way the boss sez it must be done!” and “because that’s the way we’ve always done it!” aren’t honorable reasons for maintaining the status quo? If so, then dishonorable behavior runs rampant within the halls of most software shops the world over. But you already knew that, no?

Unavailability II

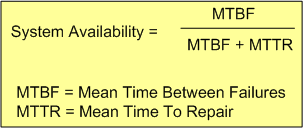

The availability of a software-intensive, electro-mechanical system can be expressed in equation form as:

With the complexity of modern day (and future) systems growing exponentially, calculating and measuring the MTBF of an aggregate of hardware and (especially) software components is virtually impossible.

Theoretically, the MTBF for an aggregate of hardware parts can be predicted if the MTBF of each individual part and how the parts are wired together, are “known“. However, the derivation becomes untenable as the number of parts skyrockets. On the software side, it’s patently impossible to predict, via mathematical derivation, the MTBF of each “part“. Who knows how many bugs are ready to rear their fugly heads during runtime?

From the availability equation, it can be seen that as MTTR goes to zero, system availability goes to 100%. Thus, minimizing the MTTR, which can be measured relatively easily compared to the MTBF ogre, is one effective strategy for increasing system availability.

The “Time To Repair” is simply equal to the “Time To Detect A Failure” + “The Time To Recover From The Failure“. But to detect a failure, some sort of “smart” monitoring device (with its own MTBF value) must be added to the system – increasing the system’s complexity further. By smart, I mean that it has to have built-in knowledge of what all the system-specific failure states are. It also has to continually sample system internals and externals in order to evaluate whether the system has entered one of those failures states. Lastly, upon detection of a failure, it has to either inform an external agent (like a human being) of the failure, or somehow automatically repair the failure itself by quickly switching in a “good” redundant part(s) for the failed part(s). Piece of cake, no?

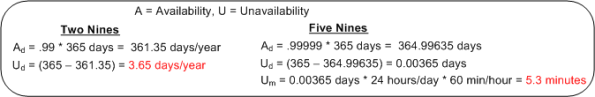

Unavailable For Business

The availability of a system is usually specified in terms of the “number of nines” it provides. For example, a system with an availability specification of 99.99 provides “two nines” of availability. As the figure below shows, a service that is required to provide five nines of availability can only be unavailable 5.3 minutes per year!

Like most of the “ilities” attributes, the availability of any non-trivial system composed of thousands of different hardware and software components is notoriously difficult and expensive to predict or verify before the system is placed into operation. Thus, systems are deployed and fingers crossed in the hope that the availability it provides meets the specification. D’oh!

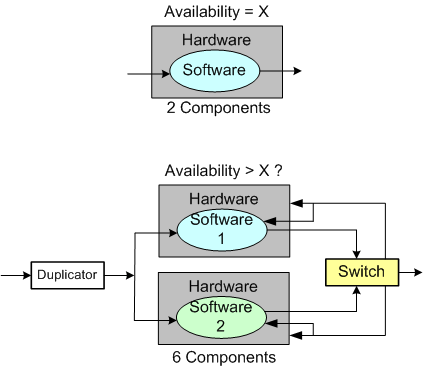

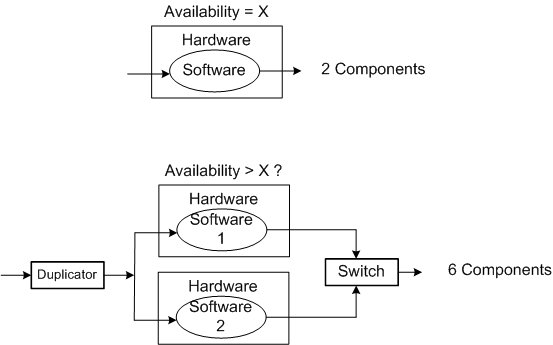

One way of supposedly increasing the availability of a system is to add redundancy to its design (see the figure below). But redundancy adds more complex parts and behavior to an already complex system. The hope is that the increase in the system’s unavailability and cost and development time caused by the addition of redundant components is offset by the overall availability of the system. Redundancy is expensive.

As you might surmise, the switch in the redundant system above must be “smart“. During operation, it must continuously monitor the health of both output channels and automatically switch outputs when it detects a failure in the currently active channel.

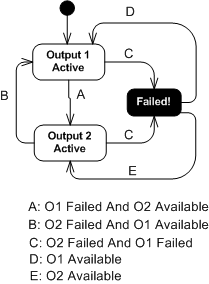

The state transition diagram below models the behavior required of the smart switch. When a switchover occurs due to a detected failure in the active channel, the system may become temporarily unavailable unless the redundant subsystem is operating as a hot standby (vs. cold standby where output is unavailable until it’s booted up from scratch). But operating the redundant channel as a hot standby stresses its parts and decreases overall system availability compared to the cold spare approach. D’oh!

Another big issue with adding redundancy to increase system availability is, of course, the BBoM software. If the BBoM running in the redundant channel is an exact copy of the active channel’s software and the failure is due to a software design or implementation defect (divide by zero, rogue memory reference, logical error, etc), that defect is present in both channels. Thus, when the switch dutifully does its job and switches over to the backup channel, it’s output may be hosed too. Double D’oh! To ameliorate the problem, a “software 2” component can be developed by an independent team to decrease the probability that the same defect is inserted at the same place. Talk about expensive?

Achieving availability goals is both expensive and difficult. As systems become more complex and human dependence on their services increases, designing, testing, and delivering highly available systems is becoming more and more important. As the demand for high availability continues to ooze into mainstream applications, those orgs that have a proven track record and deep expertise in delivering highly available systems will own a huge competitive advantage over those that don’t.

Stress Particles

In a terrific duo of videos, George Pransky makes the observation that most people believe unequivocally that stress is objectively “out there“. He makes an analogy with fictional “stress particles“. Ya gotta stay away from places and events that are infested with stress particles, lest your physical health, mental health, and quality of life deteriorate as a result of becoming contaminated.

The fact of the matter is that all stress is man-made. To be more specific, all stress is self-made. Granted, it’s hard to argue that events such as job loss, divorce, moving, and the death of a loved one aren’t stressful, but the intensity of suffering one experiences is person-specific, no?

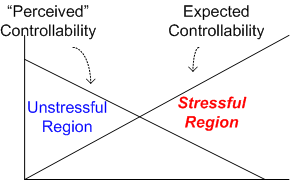

I think the amount of stress one manufactures for oneself is a function of one’s perceived control over situations and the degree with which one expects to have control. Control freaks who are in environments where they can’t or aren’t allowed to exercise control create more stress for themselves than non-control freaks. Control freak or not, environments where an individual can control his/her activities and influence the environment are perceived as less stressful.

As can be inferred from the diagram, there are at least two ways to increase one’s “unstressful” region while decreasing one’s “stressful” region. Reduce expectations or increase perceived controllability. A better way is to realize the truth of the matter – there is no controllability, there’s only the ability to influence.

Growing Wings On The Way

If you don’t have wings and you jump off a cliff, you better hope to grow a pair before you go splat. With this lame ass intro, I introduce you to the title of the latest systems thinking book that I finished reading: “Growing Wings On The Way“.

GWOTW is yet another terrific systems thinking book from small British publishing house “Triarchy Press“. The book defines and explains a myriad of tools/techniques for coming to grips with, understanding, and improving, socio-technical “messes“. Through numerous examples, including a very personal one, Rosalind Armson develops the thought processes and methods of inquiry that can allow you to generate rich pictures, influence diagrams, system maps, multiple-cause diagrams, and human activity system diagrams for addressing your “messes“. If you want a solid and usable intro to soft systems thinking, then this may be your book.