Archive

A Big Fat Waste Of Time

Having recently finished the above two heretical books on the undiscussable joke that is “the Annual Performance Review“, I coincidentally stumbled upon this recent FastCompany.com article: “Why Year-End Reviews Are A Big Fat Waste Of Time”.

Alas, even though author Denis Wilson plants some decent advice for managers in the blarticle, it still reeks of a slight “tweak” to the notoriously bad, but eerily unopposed, APR practice.

After posting the link to the blarticle on Twitter, I had this interesting exchange with Adam Yuret:

Upon reflection on why such a horrendously demeaning practice like the APR still exists in the 21st century, BD00 has come to the conclusion that the guild of management collectively thinks:

- The APR actually “works” or,

- They know it doesn’t work but they have no motivation to attempt such a big and scary change to the org, or

- They know it doesn’t work but they have no motivation to explore alternatives for achieving what the APR is actually supposed to do.

Three Degrees Of Distribution

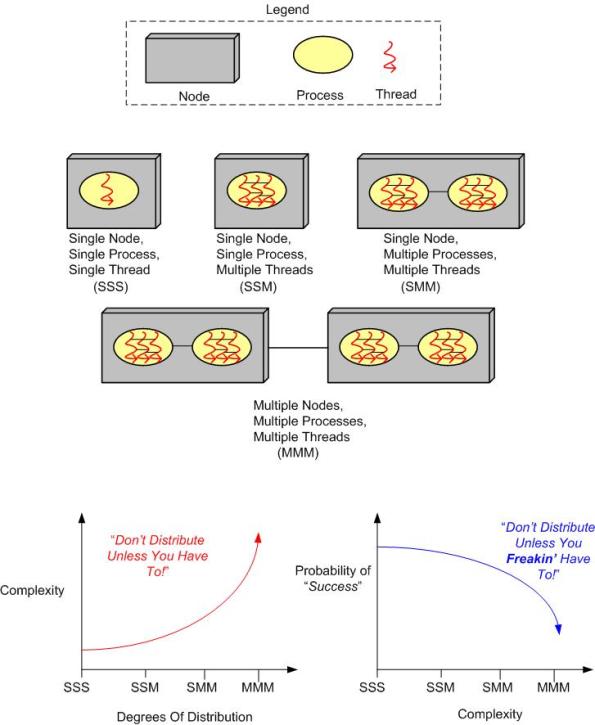

Behold the un-credentialed and un-esteemed BD00’s taxonomy of software-intensive system complexity:

How many “M”s does the system you’re working on have? If the answer is three, should it really be two? If the answer is two, should it really be one? How do you know what number of “M”s your system design should have? When tacking on another “M” to your system design because you “have to“, what newly emergent property is the largest complexity magnifier?

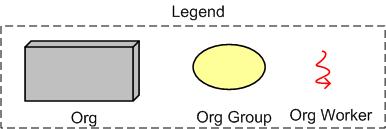

Now, replace the inorganic legend at the top of the page with the following organic one and contemplate how the complexity and “success” curves are affected:

I-Speak

I don’t know where I read it, but I remember someone giving great advice about using “I-Speak” to present your case on a sensitive issue. Don’t go blasting away and saying stuff like “everyone thinks the system is a freakin’ disaster“. Instead, say “I have a hard time using the system as it’s designed“.

In really uptight and unresponsive groups, preface your concern with “I can only speak for myself, but…“. But don’t forget, in zero tolerance bureaucracies, keep your “I” trap totally shut tight and keep toiling along in quiet desperation.

Underlying Assumptions

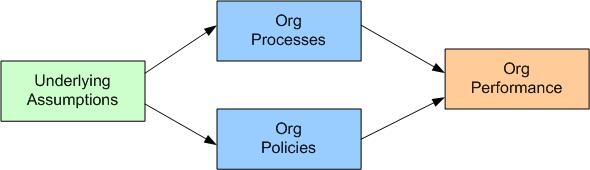

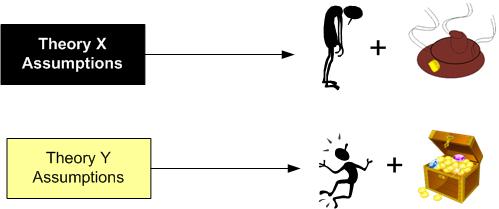

The underlying assumptions harbored by executive decision-makers drive an org’s processes/policies. And those processes/policies influence an org’s social and financial performance. As a rule, assumptions based on Theory X thinking lead to mediocre performance and those based on Theory Y lead to stellar performance. Most org processes/policies (e.g. the annual “objective” performance appraisal ritual) are Theory X based constrictions cloaked in Theory Y rhetoric – regardless of what is espoused.

Preventers, Not Managers

The worst companies directly contribute to the physical and emotional deterioration of their DICforces by unceasingly imposing ridiculous schedules and ratcheting up the (unspoken) pressure to work massive amounts of unpaid overtime for long stretches of time. Average companies do the same under the tired old mantra of “it’s a hostile business environment“, but they take good care of their DICsters after much damage is done. The best of the breed are highly self-aware systems that actively practice “crisis prevention” – not “crisis management“. They diligently monitor the “system’s” vital signs and know when things are getting too toxic for their people. Unlike the worst and the average, the best actually take effective action to relieve the stress on their people before the wreckage accumulates. They’ll sacrifice some almighty dollars by relaxing schedules, or giving some extra days off, or frequently providing small tokens of appreciation to counter the toxicity of the operational environment. They are preventers, not managers.

Wouldn’t it be kool if the role of “manager” was jettisoned in favor of “preventer“? If anything, it would at least drive home what those in charge of others should really be doing – preventing, not managing.

Ignored, Denied, Or Pushed Aside

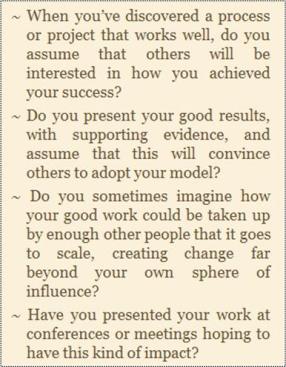

Fresh from Margaret Wheatley‘s “So Far from Home: Lost and Found in Our Brave New World“, I present you with these four vexing questions:

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions and your expectations were met, then you’re incredibly lucky because:

They’re based on an assumption of rational human behavior— that leaders are interested in what works— and that has not proven true. Time and again, innovators and their highly successful projects are ignored, denied or pushed aside, even in the best of times. In this dark era, this is even more true. – Margaret Wheatley

Not that I’m an innovator, but these questions hit me hard because it took decades of disappointment and bewilderment for me to realize that Ms. Wheatley is right. But you know what? Once I became truly aware that “it is the way it is“, I felt liberated. Now I do the work for the work itself. An intimate, joyful communication between the creator and the created.

Quantum Chaotic Complexity

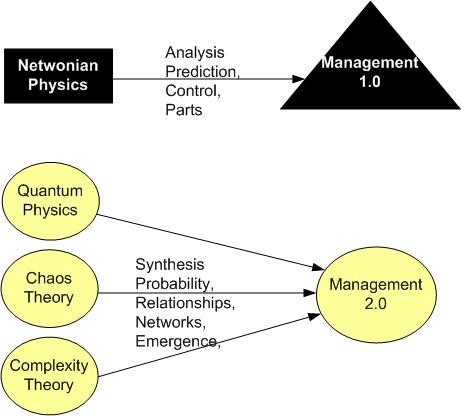

How many institutions are still being managed in accordance with the knowledge learned from 17th century physics? These days, its networks and relationships, not billiard balls and force.

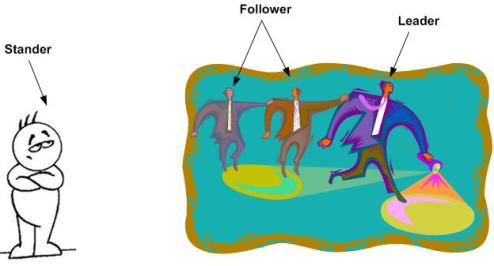

Leaders, Followers, Standers

Everybody knows what leaders and followers are, but what about “standers“? A stander is not a slacker. It’s a capable person who is content to stay within his/her comfort zone doing the same thing over and over again.

BD00 thinks that all people are capable and they innately want to “move” forward either as a leader or a follower. It’s a social system’s culture that molds “standers” out of capable people.

In cultures where mistakes of commission are penalized and mistakes of omission go undetected and unacknowledged, the optimum strategy, courtesy of Russell Ackoff, is simply to do as little as needed to elude ex-communication. It’s stagnation city with a burgeoning population of standers; sad for the people and sad for the org.

A Stone Cold Money Loser

A widespread and unquestioned assumption deeply entrenched within the software industry is:

For large, long-lived, computationally-dense, high-performance systems, this attitude is a stone cold money loser. When the original cast of players has been long departed, and with hundreds of thousands (perhaps millions) of lines of code to scour, how cost-effective and time-effective do you think it is to hurl a bunch of overpaid programmers and domain analysts at a logical or numerical bug nestled deeply within your golden goose. What about an infrastructure latency bug? A throughput bug? A fault-intolerance bug? A timing bug?

Everybody knows the answer, but no one, from the penthouse down to the boiler room wants to do anything about it:

To lessen the pain, note that to be “kind” (shhh! Don’t tell anyone) BD00 used the less offensive “artifacts” word – not the hated “D” word. And no, I don’t mean huge piles of detailed, out-of-synch, paper that would torch your state if ignited. And no, I don’t mean sophisticated-looking, semantic-less garbage spit out by domain-agnostic tools “after” the code is written.

Wah, wah, wah:

- “But it’s impossible to keep the artifacts in synch with the code” – No, it’s not.

- “But no one reads artifacts” – Then make the artifacts readable.

- “But no one knows how to write good artifacts” – Then teach them.

- “But no one wants to write artifacts” – So, what’s your point? This is a business, not a vacation resort.

Under Or Over?

In general, humans suck at estimating. In specific, (without historical data,) software engineers suck at estimating both the size and effort to build a product – a double whammy. Thus, the bard is wrong. The real thought worth pondering is:

To underestimate or overestimate, that is the question.

In “Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art“, Steve McConnell boldly answers the question with this graph:

As you can see, the fiscal penalty for underestimation rockets out of control much quicker than the penalty for overestimation. In summary, once a project gets into “late” status, project teams engage in numerous activities that they don’t need to engage in if they overestimated the effort: more status meetings with execs, apologies, triaging of requirements, fixing bugs from quick-dirty workarounds implemented under schedule duress, postponing demos, pulling out of trade shows, more casual overtime, etc.

So, now that the under/over question has been settled, what question should follow? How about this scintillating selection:

Why do so many orgs shoot themselves in the foot by perpetuating a culture where underestimation is the norm and disappointing schedule/cost performance reigns supreme?

Of course, BD00 has an answer for it (cuz he’s got an answer for everything):

Via the x-ray power of POSIWID, it’s simply what hierarchical command and control social orgs do; and you can’t ask such an org to be what it ain’t.