Archive

Measuring Clock Resolution

The Boost.Date_Time C++ library provides an excellent, platform-independent set of interrelated classes for measuring and tracking times and dates during program operation. It is much more capable and, more importantly, accurate than the standard C++ <ctime> library inherited from C. Since we need to benchmark the average and peak latency for our growing distributed, real-time, system infrastructure running on Linux, Solaris and (maybe) Win32 platforms, I decided to use the Boost.Date_Time functionality to measure the clock resolution on a representative of each platform.

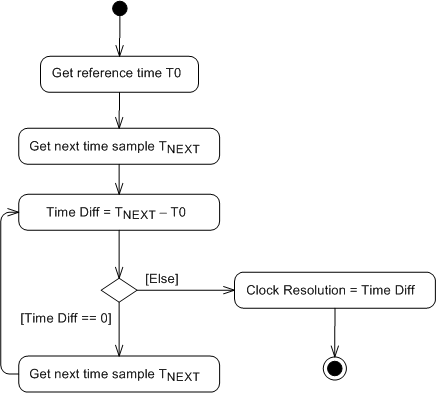

The UML activity diagram below shows the simple algorithm that I used to write a small program that estimates the clock resolution of any compiler-CPU-OS platform combo that Boost.Date_Time is available for. The assumption underlying the design is that the program instructions inside the loop execute an order of magnitude faster than a clock tick increments. At CPU speeds on the order of GHz ( nanoseconds) and clock periods of microseconds, this is a pretty decent assumption, no? The algorithm simply spins around in a tight, high speed loop waiting for the clock to change value relative to an initial reference sample. Note that measuring hardware clock accuracy is another story (Does anyone know if clock hardware accuracy can even be estimated in software?).

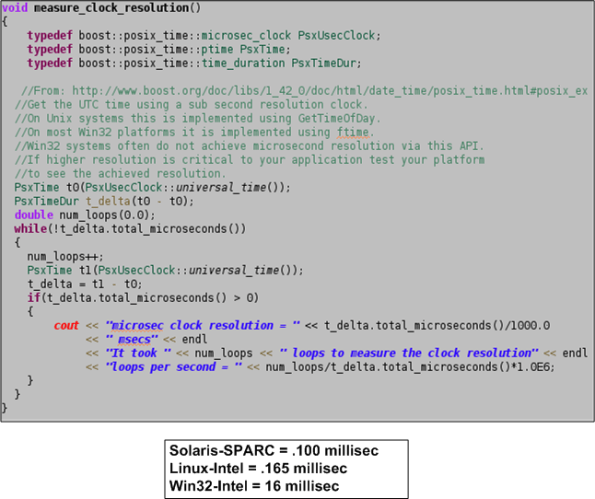

The function below shows the super secret, proprietary, source code that uses the Boost.Date_Time facilities to implement the clock resolution estimation algorithm. Note that the boost microseconds clock, as opposed to the nanoseconds or seconds clock, is used to grab time samples. The seconds clock is too coarse grained for our needs and typical off-the-shelf servers do not provide hardware clocks with nanosecond resolutions without add on circuitry. The box below the code shows the results that I obtained for three platforms on which I ran the program. Of course, the results aren’t perfect (are any results ever perfect?), but since the Solaris and Linux results provide sub-millisecond resolution and we expect end-to-end system latencies on the order of hundreds of milliseconds, the clocks will satisfy our latency measurement needs. Of course, the Win32 result is crappy. Got any thoughts?

Don’t Be Late!

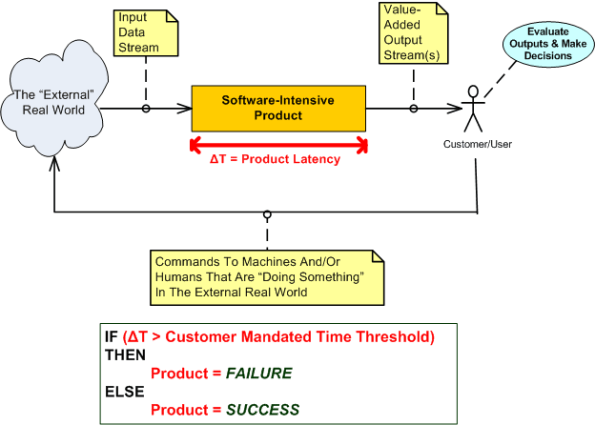

The software-intensive products that I get paid to specify, design, build, and test involve the real-time processing of continuous streams of raw input data samples. The sample streams are “scrubbed and crunched” in order to generate higher-level, human interpretable, value-added, output information and event streams. As the external stream flows into the product, some samples are discarded because of noise and others are manipulated with a combination standard and proprietary mathematical algorithms. Important events are detected by monitoring various characteristics of the intermediate and final output streams. All this processing must take place fast enough so that the input stream rate doesn’t overwhelm the rate at which outputs can be produced by the product; the product must operate in “real-time”.

The human users on the output side of our products need to be able to evaluate the output information quickly in order to make important and timely command and control decisions that affect the physical well-being of hundreds of people. Thus, latency is one of the most important performance metrics used by our customers to evaluate the acceptability of our products. Forget about bells and whistles, exotic features, and entertaining graphical interfaces, we’re talking serious stuff here. Accuracy and timeliness of output are king.

Latency (or equivalently, response time) is the time it takes from an input sample or group of related samples to traverse the transformational processing path from the point of entry to the point of egress through the software-dominated product “box” or set of interconnected boxes. Low latency is good and high latency is bad. If product latency exceeds a time threshold that makes the output effectively unusable to our customers , the product is unacceptable. In some applications, failure of the absolute worst case latency to stay below the threshold can be the deal breaker (hard real time) and in other applications the average latency must not exceed the threshold xx percent of the time where xx is often greater than 95% (soft real time).

Latency is one of those funky, hard-to-measure-until-the-product-is-done, “non-functional” requirements. If you don’t respect its power to make or break your wonderful product from the start of design throughout the entire development effort, you’ll get what you deserve after all the time and money has been spent – lots of rework, stress, and angst. So, if you work on real-time systems, don’t be late!