Archive

Herman Miller’s Design for Growth

Herman Miller Inc, of Aeron chair fame, is a rare breed. They consistently morph with the times and remain profitable in turbulent waters. This article, Herman Miller’s Design for Growth, tells the compelling story of the genesis of a new suite of products named Convia that spawned a brand new subsidiary business.

The terrific strategy + business article not only recounts the technical story behind the convia product line, it tells the story of the innovative management practices employed by the company’s leadership over the lifetime of the company:

The creation of Convia might sound like a tale of pure product innovation, or even of technology adoption, but it is actually a story about management — and only the most recent of several similar stories at Herman Miller. Over many decades, the company has made itself a laboratory for testing new management ideas and turning them into effective practice.

First, the hard evidence that the company is highly successful despite its repeated forays into the unknown:

Herman Miller competes in an industry slammed by arguably the worst commercial real-estate crisis in a generation. Still, despite a 19 percent plunge in sales for fiscal 2009 (ending in May), the US$1.6 billion company reported a $68 million profit, albeit down from $152 million in fiscal 2008. Over the last 10 years, its stock has consistently outperformed the Standard & Poor’s 500 index.

Next, the snippets that yield insights into the off-the-beaten-path management mindset of the company’s leaders:

…two key principles that continue to inform the company’s management approach. One was a commitment to participative management; the other, a problem-solving approach to design.

Max De Pree, CEO from 1980 to 1987, drew broad attention to the culture at Herman Miller by writing the bestselling Leadership Is an Art (Dell, 1990). Of participative management, he wrote: “Each of us, no matter what our rank in the hierarchy may be, has the same rights: to be needed, to be involved, to have a covenantal relationship, to understand the corporation, to affect our destiny, to be accountable, to appeal, to make a commitment.”

He (Brian Walker, the company’s former chief financial officer, who took over as CEO in 2004) wanted everyone at the company to calculate the financial effect of decisions big and small. It didn’t matter if they were involved in buying, selling, building, designing, billing, paying, or financing. Or whether they were charged with controlling quality, reliability, inventory, waste, energy use, scrap, or the kinds of staples people used.

As Long (now director of the corporate HMPS team) toured the file cabinet plant recently, a visitor paused by a welding robot and asked, “Why don’t you use more robots?” “Robots,” Long said, “can’t make themselves better.”

The objective was to have top decision makers invest themselves in the work — to be companions on the journey, not simply judges of it. “The idea,” Miller says, “was to change the dynamic from traditional review-and-approve to advocacy.”

But Walker argued that in the feeble economy, the main goal was to keep the business sustainable, not to increase profitability at the expense of employees.

Walker says he has no regrets about paying people for time not worked, as the program generated a lot of goodwill and credibility for top management.

So, what do you think? Is the image of Herman Miller Inc. different from the stale corpo model entrenched in your brain?

Three Types

One simple (simplistic?) way of looking at how orgs of people operate is by classifying them into three abstract types:

- The Malevolent Patriarchy

- The Benevolent Patriarchy

- The Meritocracy

Since it’s so uncommon and rare to find a non-patriarchically run org (which is so pervasive that the genre includes small, husband-wife-children, families like yours and mine), I struggled with concocting the name of the third type. Got a better name?

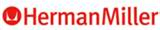

The figure below shows a highly unscientific family of maturation trajectories that an org can take after “startup”. The ubiquitous, well worn path that is tread as an org grows in size is the Meritocracy->Benevolent Patriarchy->Malevolent Patriarchy sojourn. Note that there are no reverse transitions in any of the trajectories. That’s because reverse state changes, like a Benevolent Patriarchy-to-Meritocracy transformation, are as rare as a company remaining in the Meritocracy state throughout its lifetime.

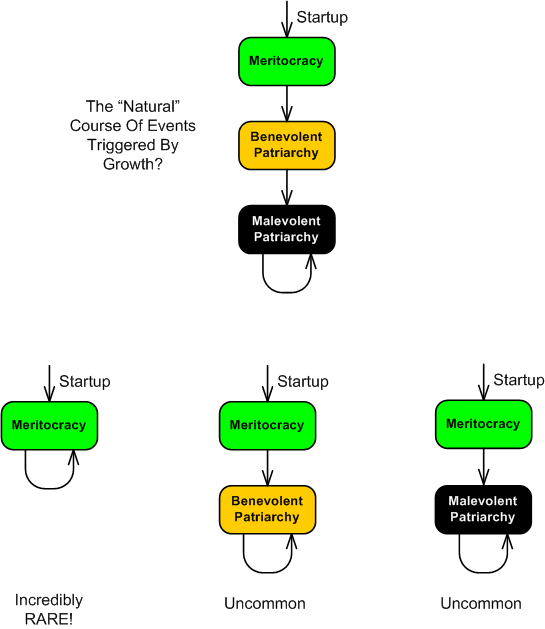

The state versus time graph below communicates the same information as the state machine family above, but from a time-centric viewpoint. Since “all models are wrong, but some are useful” (George Box), the instantaneous transition points, T1 and T2, are wrong. These insidious transitions occur so gradually and so slooowly that no one, not even the So-Called Org Leadership (SCOL), notices a state change. Bummer, no?

A $1.6M Mistake – And No One Was Fired

The other day, I discovered that a human mistake made on Zappos.com’s sister web site, 6pm.com, emptied the company’s coffers of $1.6 million dollars. Being the class act that he is, here’s what CEO Tony Hsieh had to say regarding the FUBAR:

To those of you asking if anybody was fired, the answer is no, nobody was fired – this was a learning experience for all of us. Even though our terms and conditions state that we do not need to fulfill orders that are placed due to pricing mistakes, and even though this mistake cost us over $1.6 million, we felt that the right thing to do for our customers was to eat the loss and fulfill all the orders that had been placed before we discovered the problem. – Tony Hsieh, CEO, Zappos.com

If this happened at your company, what would your management do? Do ya think they’d look at it as a learning experience?

Besides Zappos.com, here are the other companies that I love. What are yours, and is the company you work for one of them?

Spreading Happiness

Just like last year, as soon as I heard that Zappos.com’s 2009 culture book was available, I e-mailed the company to get one. Just like last year, I received my free, postage paid copy in the mail three days later. What a great way to spread happiness, no?

Right on page number 1, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh states:

People may not remember exactly what you did or what you said, but they will always remember how you made them feel.

Who says there is no room in business for emotions? Ninety-nine percent of business schools and business executives do, that’s who: “It’s not personal, it’s business.” Over the years I’ve learned to question the assumptions that institutional bozeltines, oops, leaders operate under. Sadly, I’ve discovered that most of those taken-for-granted, 100 year old assumptions like “the separation of feeling from work” don’t hold true anymore. How about you?

Undiscussable Unfairness

Assume that two similar projects are underway at your company. Also, assume that one of the teams is encumbered by a heavyweight process and the other is given a blank check to do as they please – no processes or procedures to follow, no external reviewers, no forms to fill out, no design or maintenance documentation to be generated. Would you confront management about the inequity? If so, why would you do something so stupid? Don’t you think the dudes in charge know what they’re letting happen? Don’t you think they would be pissed at you for pointing out the obvious but undiscussable stank of unfairness in the air?

I think perfect objectivity is an unrealistic goal; fairness, however, is not. – Michael Pollan

Competitive Edge

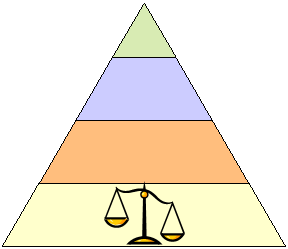

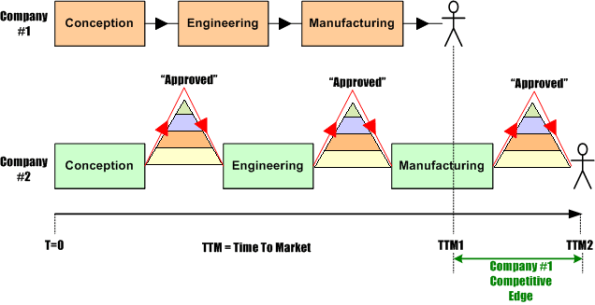

Check out the figure below. Which model more closely maps to your company’s way of operating?

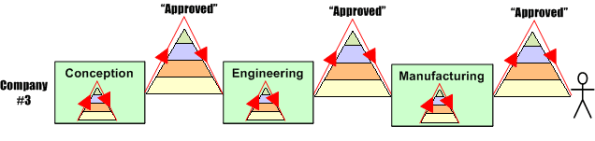

If you picked company #2, does the nested approval model below represent your company even more closely? Does every swingin’ dick (not DIC) in the house with one or more titles feel the need to be informed and bestow his/her approval before anything of substance can get done within the corpo citadel?

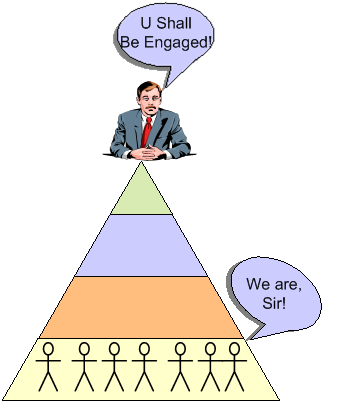

Engage Me, Please

Since many people spend a large amount of time at work, or thinking about work, I’ve been on a perpetual search for the keys to developing, and more importantly, sustaining an inspirational culture that brings daily joy to all. I’m keenly interested in the topic because an inspiring company culture, like quality, is ephemeral, hard to quantify, and hard to bring to fruition.

In this blog post, “The Hole In The Soul Of Business“, Gary Hamel laments the fact that so many business leaders come up empty when it comes to the creation and sustainment of an engaging company culture.

In my last post, I cited a survey that found that only 20% of employees are truly engaged in their work — heart and soul. As a student of management, I’m depressed by the fact that so many people find work depressing. In the study, respondents laid much of the blame for their lassitude on uncommunicative and egocentric managers…

Why is it that managers are so willing to acknowledge the idea of a company dedicated to timeless human values and yet so unwilling to become practical advocates for those values within their own organizations? I have a hunch. I think corporate life is so manifestly inhuman—so mechanical, mundane and materialistic—that any attempt to inject a spiritual note into the overtly secular proceedings just feels wildly out of place—the workplace equivalent of reading a Bible in a brothel.

The first step toward getting rid of a bad habit is admitting that you have a problem in the first place. Alas, uncommunicative and egocentric managers never admit that there is a problem. That’s because they’re infallible, of course.

Hey Nicky, Please Pass The Culture Sauce

This Inc. Magazine piece, Lessons From a Blue-Collar Millionaire, tells the story of CEO Nick Sarillo and Nick’s Pizza & Pub. Like Tony Hsieh of Zappos.com , Jim Goodnight of the SAS Institute, and Ricardo Semler of Semco, Nick knows that the real key to business success is building a people-centric culture and relentlessly husbanding it so that the second law of thermodynamics doesn’t slowly but surely destroy it.

Here are some snippets from the article followed by comments from the peanut gallery.

In an industry in which annual employee turnover of 200 percent is considered normal, Sarillo’s restaurants lose and replace just 20 percent of their staff members every year. Net operating profit in the industry averages 6.6 percent; Sarillo’s runs about 14 percent and has gone as high as 18 percent. Meanwhile, the 14-year-old company does more volume on a per-unit basis (an average of $3.5 million over the past three years) than nearly all independent pizza restaurants. And customers, it seems, adore the service: On three occasions, waitresses have received tips of $1,000.

The above results clearly show that what Nick’s doing works, no?

Sarillo has built his company’s culture by using a form of management best characterized as “trust and track.” It involves educating employees about what it takes for the company to be successful, then trusting them to act accordingly. The company’s training program is elaborate, rigorous, and ongoing. The alternative is command and control, wherein success is the boss’s responsibility and employees do what the boss says.”Managers trained in command and control think it’s their responsibility to tell people what to do,” Sarillo says. “They like having that power. It gives them their sense of self-worth. But when you manage that way, people see it, and they start waiting for you to tell them what to do. You wind up with too much on your plate, and things fall through the cracks. It’s not efficient or effective. We want all the team members to feel responsible for the company’s success.”

There’s not much to add to the above snippet. I, and countless others much smarter and more eloquent than me, have ranted about the toxicity of dysfunctional CCH corpocracies to no avail. CCHs litter the landscape anf they will continue to do so because of Nick’s quote: “They like having that power. It gives them their sense of self-worth.”

They had someone else put in the numbers, and when the numbers came out wrong, they didn’t dig deeper to discover why. Because they didn’t know the ‘why,’ they couldn’t share it with the team members. When you know the ‘why,’ it’s really easy to figure out what to do, but sharing that kind of information wasn’t how they’d been trained to manage.”

In the above snippet, Nick relates his experience when he mistakenly hired managers with the old “I’m the boss and I don’t do details – I’m better than that” 1920’s mindset.

People who inquire about a job receive a handout detailing the company’s purpose and values. Candidates need four yes votes from three managers to receive an offer. Just one of every 12 applicants to Nick’s gets hired. “I was really surprised by the process,” she says. “You get interviewed twice, and you take a personality test.”

Like other culture-obsessed companies, the interviewing process is key to separating the wheat from the chaff.

- 1 Feel your community’s pain; share its joy

- 2 Hire only A+ players

- 3 Learn, grow, compensate

- 4 Systems are for building trust

- 5 Coach in the moment, not after the fact

- 6 A consultant can be more helpful than you think

- 7 Turn negatives into positives by making talk safe

- 8 “Why” is more important than “what” or “how”

- 9 “Trust” without “track” is an invitation to trouble

- 10 Beware of growing before you — and the company — are ready

The above list represents the 10 key ingredients that Nick uses to drive his business. My faves are numbers 4, 7, 8, and 9. What are yours?

Waiting

- “I’m waiting for the requirements specification”.

- “I’m waiting for management approval”.

- “I’m waiting for the customer’s answers to my questions”.

- “I’m waiting for QA appproval”.

- “I’m waiting for management to solidify our strategy.”

- “I’m waiting to get a software (or hardware or systems or test) engineer assigned to the project”.

- “I’m waiting for the finance department to open the charge number.”

Yada, yada, yada. On goes the list of pseudo-legitimate excuses for being late and inefficient in bureaucratic corpocracies. When a system is set up so that everything is tightly coupled and each element is highly dependent on everything else, productivity sinks, end-to-end delay increases, and it takes a miracle to get any value added work done. The funny thing is that the dudes in the bozone layer demand continuously increasing productivity while simultaneously allowing their system to deteriorate into an inflexible and intertwined mess of confusion.

SAS Still Rocks

Everyone loves to be number one. According to Fortune mag, SAS is the Best Company to Work For in 2010. This rare gem of a company has been on my list of faves for many years and it amazingly continues to thrive in a rapidly moving industry that’s under constant pressure from competitors like Google, IBM, Microsoft, and open source software organizations.

SAS (pronounced sass) has been on Fortune’s list of Best Companies to Work For every one of the 13 years we’ve been keeping score. But this is the first time SAS is in the No. 1 slot.

CEO Jim Goodnight’s motives aren’t charitable but entirely utilitarian, even a bit Machiavellian. The average tenure at SAS is 10 years; 300 employees have worked 25 or more. Annual turnover was 2% in 2009, compared with the average in the software industry of about 22%. Women make up 45% of its U.S. workforce, which has an average age of 45.

Goodnight says the “wonder” isn’t that his company is so generous, but why other presumably rational corporations are not. Academicians confirm that his policies augment creativity, reduce distraction, and foster intense loyalty — even though SAS isn’t known for paying the highest salaries in its field and even though there are no stock options.

The notion of easy living frustrates those on the inside. “Some may think that because SAS is family-friendly and has great benefits that we don’t work hard,” says Bev Brown, who’s in external communications. “But people do work hard here, because they’re motivated to take care of a company that takes care of them.”

With a “billion dollars in the bank” and another big building going up on campus, Goodnight is continuing to invest. In a company of elite quantitative analysts, he devotes more than a fifth of revenue to R&D. For 33 straight years, SAS’s revenues have gone up — reaching $2.3 billion in 2009, nearly doubling in seven years.

The company that I work for, Sensis Inc., is pretty damn good to its employees too. Just because I’m on a diet doesn’t mean I can’t look at the menu.