Archive

Constrained Evolution

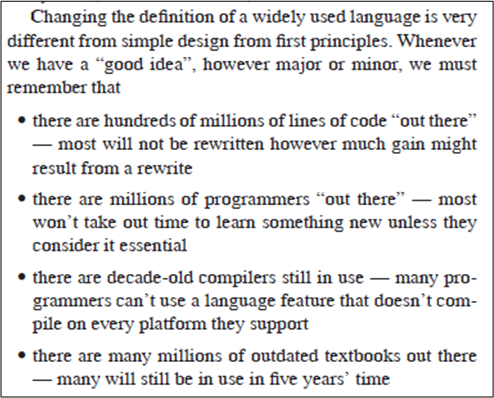

In general, I’m not a fan of committee “output“. However, I do appreciate the work of the C++ ISO committee. In “Evolving a language in and for the real world”, Bjarne Stroustrup articulates the constraints under which the C++ committee operates:

Bjarne goes on to describe how, if the committee operated with reckless disregard for the past, C++ would fade into obscurity (some would argue that it already has):

Personally, I like the fact that the evolution of C++ (slow as it is) is guided by a group of volunteers in a non-profit organization. Unlike for-profit Oracle, which controls Java through the veil of the “Java Community Process“, and for-profit Microsoft, which controls the .Net family of languages, I can be sure that the ISO C++ committee is working in the interest of the C++ user base. Language governance for the people, by the people. What a concept.

Vector Performance

std::vector, or built-in array, THAT is the question – Unshakenspeare

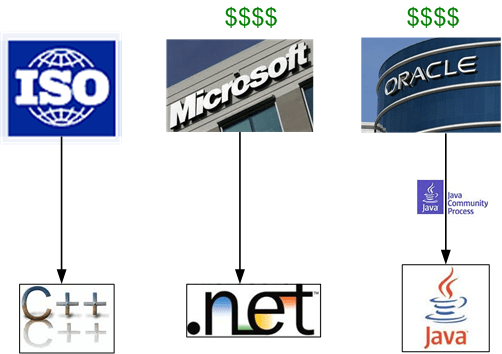

In C++, all post-beginner programmers know about the performance vs. maintainability tradeoff regarding std::vector and built-in arrays. Because they’re less abstract and closer to the “metal“, read/write operations on arrays are faster. However, unlike a std::vector container, which stores its size cohesively with its contents, every time an array is passed around via function calls, the size of the array must also be explicitly passed with the “pointer” – lest the callees loop themselves into never never land cuz they don’t know how many elements reside within the array (I hate when that happens!).

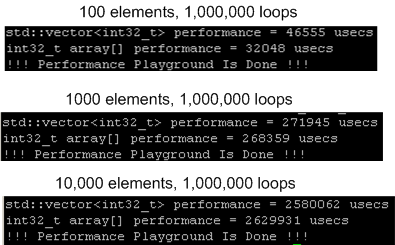

To decide which type to use in the critical execution path on the project that I’m currently working on, I whipped up a little test program (available here) to measure the vector/array performance difference on the gcc/linux/intel platform that we’re developing on. Here are the results – which consistently show a 60% degradation in performance when a std:vector is used instead of a built-in array. I thought it would be lower. Bummer.

But wait! I ain’t done yet. After discovering that I was compiling with the optimizer turned off (-O0), I rebuilt and re-ran with -O3. Here are the results:

Unlike the -O0 test runs, in which the measured performance difference was virtually independent of the number of elements stored within the container, the performance degradation of std::vector decreases as the container size increases. Hell, for the 10K element, 1M loop run, the performance of std::vector was actually 2% higher than the plain ole array. I’ve deduced that std::vector::operator[] is inlined, but when the optimizer is turned “off“, the inlining isn’t performed and the function call overhead is incurred for each elemental access.

If you’re so inclined, please try this experiment at home and report your results back here.

Something’s Uh Foot?

It’s my understanding that the financial crisis was precipitated by the concoction of exotic investment instruments like derivatives and derivatives of derivatives that not even quantum physicists could understand.

Well, it looks like the shenanigans may not be over. Take a look at this sampling of astronomically high paying jobs from LinkedIn.com for C++ programmers:

Did the financial industry learn a lesson from the global debacle, or was it back to business as usual when the dust settled? Hell, I don’t know. That’s why I’m askin’ you.

The Parallel Patterns Library

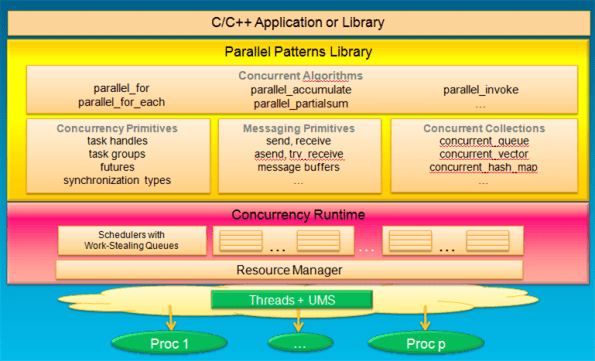

Kate Gregory doesn’t work for Microsoft, but she’s a certified MVP for C++. In her talk at Tech Ed North America, “Modern Native C++ Development for Maximum Productivity”, she introduced the Parallel Patterns Library (PPL) and the concurrency runtime provided in Microsoft Visual C++ 2010.

The graphic below shows how a C++ developer interfaces with the concurrency runtime via the facilities provided in the PPL. Casting aside the fact that the stack only runs on Windows platforms, it’s the best of both worlds – parallelism and concurrency.

Note that although they are provided via the “synchronization types” facilities in the PPL, writing multi-threaded programs doesn’t require programmers to use error-prone locks. The messaging primitives (for inter-process communication) and concurrent collections (for intra-process communication) provide easy-to-use abstractions over sockets and locks programming. The messy, high-maintenance details are buried out of programmer sight inside the concurrency runtime.

I don’t develop for Microsoft platforms, but if I did, it would be cool to use the PPL. It would be nice if the PPL + runtime stack was platform independent. But the way Microsoft does business, I don’t think we’ll ever see linux or RTOS versions of the stack. Bummer.

State Of The Union

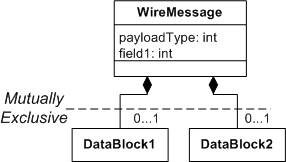

For the multi-threaded CSCI that I’m developing, I’ve got to receive and decode serialized messages off of “the wire” that conform to the design below. Depending on the value of “payloadType” in the message, each instance of the “WireMessage” class will have either an instance of “DataBlock1” or “DataBlock2” embedded within it.

After contemplating how to implement the deserialized replica of the message within my code, I decided to use a union to keep the message at a fixed size as it is manipulated and propagated forward through the non-polymorphic queues that connect the threads together in the CSCI.

The figure below shows side by side code snippets of the use of a union within a class. The code on the left compiled fine, but the compiler barfed on the code on the right with a “data member with constructor not allowed in union” error. WTF?

At first, I didn’t understand why the compiler didn’t like the code on the right. But after doing a little research, it made sense.

Unlike the code on the left, which has empty compiler-generated ctor, dtor, and copy operations, the DataBlock1 class on the right has a user-declared ctor – which trips up the compiler even though it is empty. When an object of FixedMessage type is created or destroyed, the compiler wouldn’t know which union member constructor or destructor to execute for the two class members in the union (built-in types like “int” don’t have ctors/dtors). D’oh!

Note: After I wrote this post, I found this better explanation on Bjarne Stroustrup’s C++0x FAQ page:

But of course, the restrictions on which user-defined types may be included in a union will be relaxed a bit in C++11. The details are in the link provided above.

The Emergence Of The STL

In the preface to the 2006 Japanese translation of “The Design and Evolution of C++“, Bjarne Stroustrup writes about how the C++ STL containers/iterators/algorithms approach to generic programming came into being. Of particular interest to me was how he struggled with the problem of “intrusive” containers:

The STL was a revolutionary departure from the way we had been thinking about containers and their use. From the earliest days of Simula, containers (such as lists) had been intrusive: An object could be put into a container if and only if its class had been (explicitly or implicitly) derived from a specific “Link” or “Object” class containing the link information needed by the compiler (to traverse the container). Basically, such a container is a container of references to Links. This implies that fundamental types, such as ints and doubles, can’t be put directly into containers and that the array type, which directly supports fundamental types, must be different from other containers. Furthermore, objects of really simple classes, such as complex and Point, can’t remain optimal in time and space if we want to put them into a container. It also implies that such containers are not statically type safe. For example, a Circle may be added to a list, but when it is extracted we know only that it is an Object and need to apply a cast (explicit type conversion) to regain the static type.

The figure below illustrates an “intrusive” container. Note that container users (like you and me) must conform to the container’s requirement that every application-specific, user-defined class (Element) inherits from an “overhead” Object class in order for the container to be able to traverse its contents.

As the figure below shows, the STL’s “iterator” concept unburdens the user’s application classes from having to carry around the extra overhead burden of a “universal“, “all-things-to-all people”, class.

The “separation of concerns” STL approach unburdens the user by requiring each library container writer to implement an Iterator class that knows how to move sequentially from user-defined object to object in accordance to how the container has internally linked the objects (tree, list, etc) and regardless of the object’s content. The Iterator itself contains the container-specific equivalent navigational information as the Object class in the “intrusive” container model. For contiguous memory type containers (array, vector), it may be implemented as a simple pointer to the type of objects stored in the container. For more complex containers (map, list) the Iterator may contain multiple pointers for fast, container-specific, traversal/lookup/insertion/removal.

I don’t know about you, but I think the STL’s implementation of containers and generic programming is uber cool. It is both general AND efficient – two desirable properties rarely found together in a programming language library:

…the performance of the STL is that it – like C++ itself – is based directly on the hardware model of memory and computation. The STL notion of a sequence is basically that of the hardware’s view of memory as a set of sequences of objects. The basic semantics of the STL maps directly into hardware instructions allowing algorithms to be implemented optimally. The compile-time resolution of templates and the perfect inlining they support is then key to the efficient mapping of high level expression of the STL to the hardware level.

DataLoggerThread

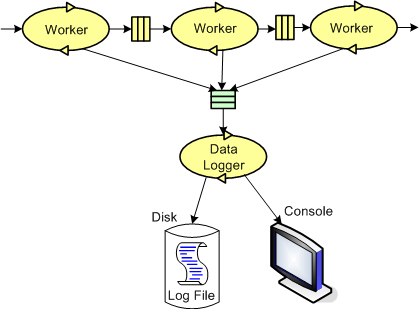

The figure below models a program in which a pipeline of worker threads communicate with each other via message passing. The accordion thingies ‘tween the threads are message queues that keep the threads loosely coupled and prevent message bursts from overwhelming downstream threads.

During the process of writing one of these multi-threaded programs to handle bursty, high rate, message streams, I needed a way to periodically extract state information from each thread so that I could “see” and evaluate what the hell was happening inside the system during runtime. Thus, I wrote a generic “Data Logger” thread and added periodic state reporting functionality to each worker thread to round out the system:

Because the reporting frequency is low (it’s configurable for each worker thread and the default value is once every 5 seconds) and the state report messages are small, I didn’t feel the need to provide a queue per worker thread – YAGNI.

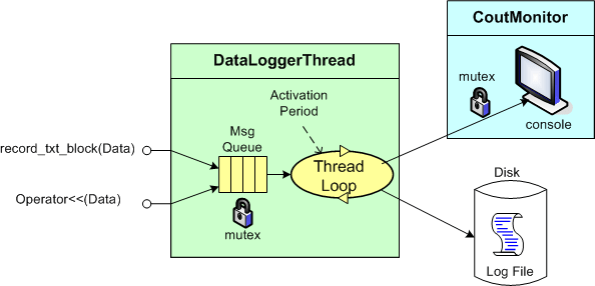

The figure below shows a more detailed design model of the data logging facility in the form of a “bent” UML class diagram. Upon construction, each DataLoggerThread object can be configured to output state messages to a user named disk file and/or the global console during runtime. The rate at which a DataLoggerThread object “pops” state report messages from its input queue is also configurable.

The DataLoggerThread class provides two different methods of access to user code at runtime:

void DataLoggerThread::record_txt_block(const Data&)

and

void DataLoggerThread::operator<<(const Data&).

Objects of the DataLoggerThread class run in their own thread of execution – transparently in the background to mainline user code. On construction, each object instance creates a mutex-protected, inter-thread queue and auto-starts its own thread of operation behind the scenes. On destruction, the object gracefully self-terminates. During runtime, each DataLoggerThread object polls its input queue and formats/writes the queue entries to the global console (which is protected from simultaneous, multiple thread access by a previously developed CoutMonitor class) and/or to a user-named disk log file. The queue is drained of all entries on each (configurable,) periodic activation by the underlying (Boost) threads library.

DataLoggerThread objects pre-pend a “milliseconds since midnight” timestamp to each log entry just prior to being pushed onto the queue and a date-time stamp is pre-pended to each user supplied filespec so that file access collisions don’t occur between multiple instances of the class.

That’s all I’m gonna disclose for now, but that’s OK because every programmer who writes soft, real-time, multi-threaded code has their own homegrown contraption, no?

My Erlang Learning Status – IV

I haven’t progressed forward at all on my previously stated goal of learning how to program idiomatically in Erlang. I’m still at the same point in the two books (“Erlang And OTP In Action“; “Erlang Programming“) that I’m using to learn the language and I’m finding it hard to pick them up and move forward.

I’m still a big fan (from afar) of Erlang and the Erlang community, but my initial excitement over discovering this terrific language has waned quite a bit. I think it’s because:

- I work in C++ everyday

- C++11 is upon us and learning it has moved up to number 1 on my priority list.

- There are no Erlang projects in progress or in the planning stages where I work. Most people don’t even know the language exists.

Because of the excuses, uh, reasons above, I’ve lowered my expectations. I’ve changed my goal from “learning to program idiomatically” in Erlang to finishing reading the two terrific books that I have at my disposal.

Note: If you’re interested in reading my previous Erlang learning status reports, here are the links:

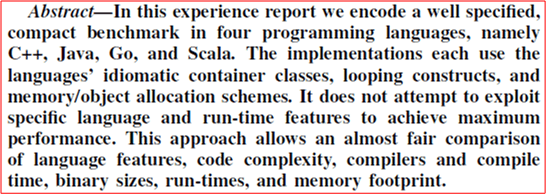

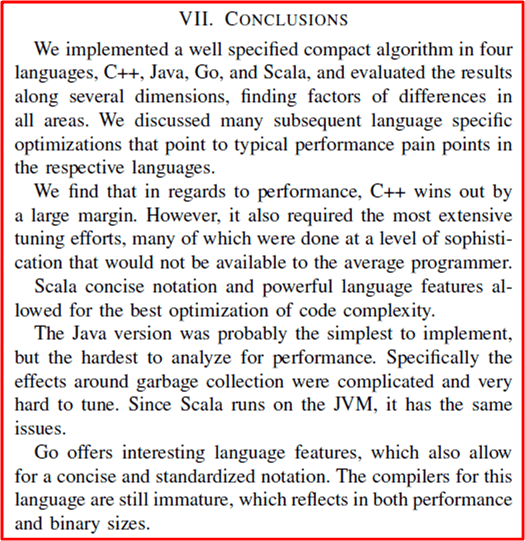

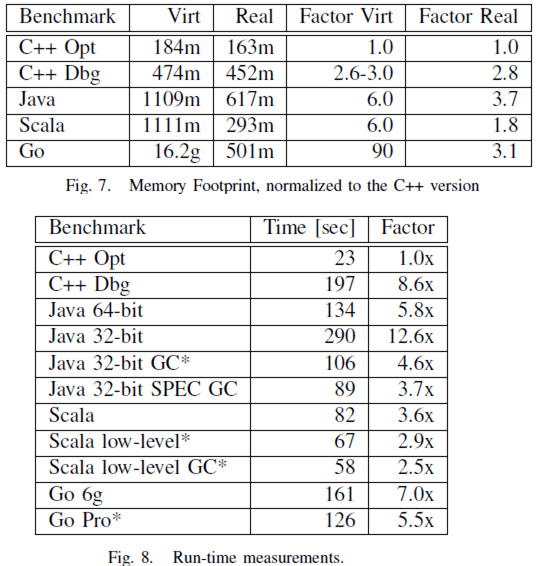

Cpp, Java, Go, Scala Performance

I recently stumbled upon this interesting paper on programming language performance from Google researcher Robert Hundt : Loop Recognition in C++/Java/Go/Scala. You can read the details if you’d like, but here are the abstract, the conclusions, and a couple of the many performance tables in the report.

Abstract

Conclusions

Runtime Memory Footprint And Performance Tables

Of course, whenever you read anything that’s potentially controversial, consider the sources and their agendas. I am a C++ programmer.

Unneeded And Unuseful

On Bjarne Stroustrup’s C++ Style and Technique FAQ web page, he answers the question of why C++ doesn’t have a “universal” Object class from which all user-defined C++ classes automatically inherit from:

I felt the need to post this here because I’m really tired of hearing Java programmers using the “lack of a universal Object class” as one reason to stake the claim that their language of choice is superior to C++. Of course, there are many other reasons in their arsenal that undoubtedly show the superiority of Java over C++.