Archive

Accessing Configuration Data

Assume that on initialization, your C++ application reads in a bunch of configuration parameters from secondary storage prior to commencing its runtime mission. Via a trio of simple UML class diagrams, the figure below shows three ways (patterns?) to structure your application to read in and store configuration data for subsequent use by the program‘s productive, value added classes (user1, user2, etc).

In the first design, a singleton class is used to read and store the runtime configuration in RAM. The singleton can either be auto-instantiated at program load time in global/namespace memory before main() executes, or the first time it is accessed by one of the program’s user objects.

In the second approach, you employ a “ConfigOwner” class that encapsulates and owns the configuration data reader class (AppConfig). On program startup, the “ConfigOwner” object instantiates the “AppConfig” reader object and then subsequently passes a reference/pointer to it to all the user objects (which the “ConfigOwner” object doesn’t own).

In the third strategy, a higher level object (AppEncapsulator) owns all other objects in the application. On startup, this parent class is instantiated first. It fully controls the initialization sequence, creating the “AppConfig” object first and then pushing a reference/pointer to it down to its child User class objects when it subsequently constructs them.

Since the application startup sequence is centrally controlled, the third, parent-child approach is totally thread-safe. The implementation of the singleton approach, where the singleton is instantiated at program load time before main() starts executing, is also thread safe. The instantiation-on-first-access singleton approach and the ConfigOwner approach are subtlely thread unsafe without some clever synchronization coding added to ensure that the AppConfig object is fully constructed before it is accessed by its users.

Since I’m not fond of using singletons in situations where they’re not absolutely required (and this is arguably one of those cases, no?) and I disdain “clever” coding, I prefer the last, centrally controlled strategy. How about you? Are you clever, or a simpleton like me?

Note: Don’t mind the bracket turd on the right of the diagram. Since I’m a lazy ass and I try not to be a perfectionist when perfection is not needed, I left the pooper in rather than removing, fixing, and reinserting the graphic into the post. Too much work.

To Call, Or To Be Called. THAT Is The Question.

Except for GUIs, I prefer not to use frameworks for application software development. I simply don’t like to be the controllee. I like to be the controller; to be on top so to speak. I don’t like to be called; I’d rather call.

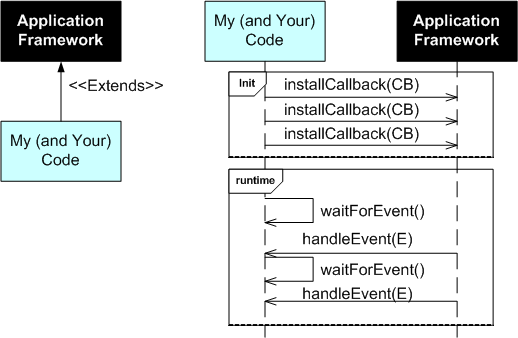

The UML figure below shows a simple class diagram and sequence diagram pair that illustrate how a typical framework and an application interact. On initialization, your code has to install a bunch of CallBack (CB) functions or objects into the framework. After initialization, your code then waits to be called by the framework with information on Events (E) that you’re interested in processing. You’re code is subservient to the Framework Gods.

After object oriented inheritance and programming by difference, frameworks were supposed to be the next silver bullet in software reuse. Well crafted, niche-based frameworks have their place of course, but they’re not the rage they once were in the 90s. A problem with frameworks, especially homegrown ones, is that in order to be all things to all people, they are often bloated beyond recognition and require steep learning curves. They also often place too much constraint on application developers while at the same time not providing necessary low level functionality that the application developer ends up having to write him/herself. Finding out what you can and can’t do under the “inverted control” structure of a framework is often an exercise in frustration. On the other hand, a framework imposes order and consistency across the set of applications written to conform to it’s operating rules; a boon to keeping maintenance costs down.

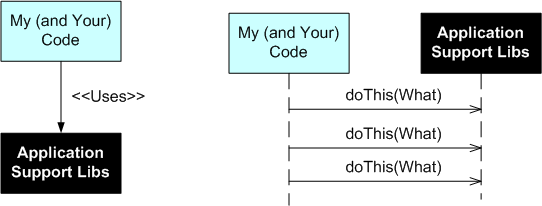

The alternative to a framework is a set of interrelated, but not too closely coupled, application domain libraries that the programmer (that’s you and me) can choose from. The UML class and sequence diagram pair below shows how application code interacts with a set of needed and wanted support libraries. Notice who’s on top.

How about you? Do you like to be on top? What has been your experience working with non-GUI application frameworks? How about system-wide frameworks like CORBA or J2EE?

How about you? Do you like to be on top? What has been your experience working with non-GUI application frameworks? How about system-wide frameworks like CORBA or J2EE?

Unconscious, Conscious, Bozo, Helper

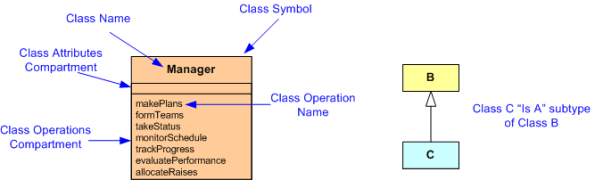

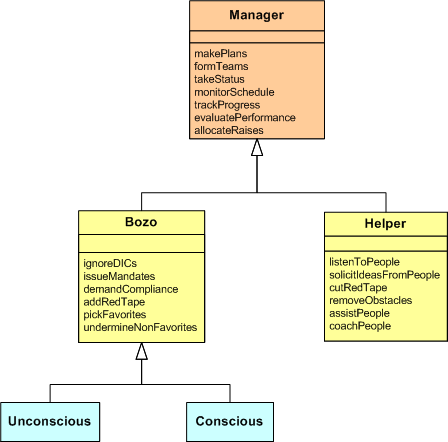

The following sparsely “bent” UML class diagram (see the end of this post for a quick and dorky tutorial for interpreting the diagram) exposes Bulldozer00’s internal hierarchy of manager types. Yours may be different, especially if you’re a manager.

The Base Class

The hierarchy’s Manager base class supplies all the mundane operations that sub-classed managers inherit and perform. For example, all managers in this particular inheritance tree make project plans, track project progress, and monitor progress against the plans. The frequency at which these behaviors are performed, along with the exact details of how they’re executed, is both manager-specific and project-specific. For example, during performance of the “takeStatus” operation, one manager may require project members to write out detailed weekly status reports whilst another may just require informal verbal status.

The Sub-Classes

The second level in Bulldozer00’s morbid and disturbing manager class hierarchy is more interesting. There are two polar opposite sub-types; Bozo and Helper. In addition to inheriting the boring, mechanical, and necessary responsibilities of the Manager base class, these subclasses provide radically different sets of behaviors. For instance, the Bozo subclass provides an “ignoreDICs” behavior whilst the Helper subclass provides “listenToPeople” and “solicitIdeas” behaviors. Comparing the behavior sets between the two subclasses and then against your own manager(s), how would you classify your manager(s)?

As the diagram shows, there are two Bozo Manager subtypes: Conscious and Unconscious. There’s no equivalent subdivision for the Helper Manager type because all Helper Manager “instantiations” are fully conscious. Hell, since all the behaviors that Helper Managers exhibit are so extraordinarily rare, productive, and against-the-grain, there is no way they can be unconscious and not know what they’re doing.

In Bulldozer00’s experience, most Bozo Managers are of the Unconscious ilk. They continuously execute the counterproductive behaviors forwarded on to them via their Bozo inheritance, but they don’t realize how detrimental their actions and words are to the orgs they’re responsible for growing and developing. Since virtually all their fellow clique members behave the same way, they’re oblivious to alternatives and they can’t connect poor org performance to their own dysfunctional behaviors.

Forgive them, for they know not what they do. – Jesus

Lastly, we come to the Conscious Bozo Manager class. Beware of these dudes, of which there are few (thank god), because they are hell on wheels. These guys/gals know fully well that their behaviors/actions are both locally and globally destructive. But why, you ask, would they behave this way? Well, because they’re out to inflate their heads and wallets and there are no boundaries they wouldn’t cross to achieve their goals.

Advice

If you choose to embrace, internalize, and use Bulldozer00’s class hierarchy to evaluate and “privately” judge your managers, you might want to take these suggestions into consideration:

- Run like hell from the Conscious Bozo types.

- Do your best to bring consciousness to the legions of well meaning, but sleepwalking, Unconscious Bozo types

- Attach yourself like a lamprey to the Helper type

But why the hell would you want to “buy into” Bulldozer00’s manager taxonomy? Great freakin’ question!

Appendix: Mini Class Diagram Graphic Tutorial

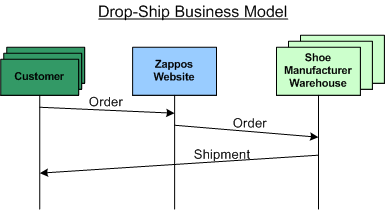

Extended Business Model

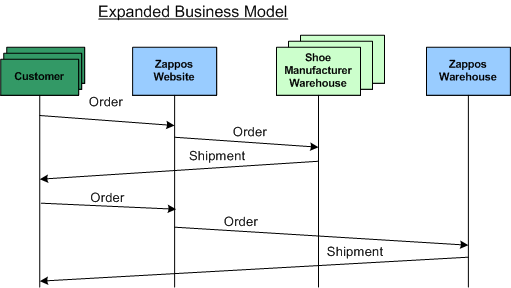

In Zappos.com CEO Tony Hsieh’s new book: “Delivering Happiness“, Tony describes the original Zappos.com business model as “drop-ship”. As the UML sequence diagram below shows, a customer would place an order at the Zappos.com website, Zappos would relay the order directly to the shoe manufacturer’s warehouse, and the order would be fulfilled and shipped directly from ground zero. It was a low cost model for Zappos, but it limited sales growth since many shoe manufacturers didn’t have the information systems in place to execute their end of the model. In addition, sales were limited to the inventory that warehouses held in storage, not necessarily what Zappos’ customers wanted.

During the initial stage of growth, Zappos.com was often short on cash (surprise!) and often just a month or two away from goin’ kaput (surprise, again!). The Zapponians needed to increase sales in order to increase cash flow. During a brainstorming session in a local bar (not in a committee of BMs, CCRATS, BOOGLs, consultants, and other self-important dudes) they came up with the idea of extending their existing business model.

Man creates by projection, nature creates by extension – Unknown

The sequence diagram below shows the extended business model that Tony “chez” et al decided to move toward. In a nutshell, Zappos would purchase or lease a warehouse and stock its own inventory based on trend information extracted from its website. As simple as it looks, the devil is in the details. Buy and read the book to learn how they pulled it off – despite being cash poor and close to going tits-up.

If changing our business model is what’s going to save us, then we need to embrace and drive change. – Tony Hsieh

How many times have you heard or spoken the “embrace change” words above but never experienced or executed any follow through?

A Blessing And A Curse

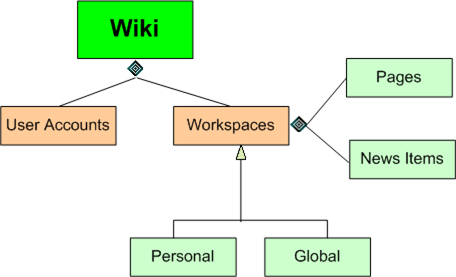

The figure below depicts a UML class diagram model of the static structure of a typical Wiki system. A Wiki may be comprised of many personally controlled and/or global workspaces. Each logical workspace is composed of user created work pages and news items (a.k.a. blog posts). Lastly, a Wiki contains many user accounts that are either created by the users themselves or, in a more controlled environment, created by a gatekeeper system administrator. Without an account, a user cannot contribute content to the Wiki database.

Org Wikis are both a blessing and a curse. They’re a blessing for the DICforce in that they allow for close collaboration and rapid, real-time information exchange between and across teams. They also serve as an easily searchable and publicly visible record of org history.

In malevolent and stovepiped CCHs where SCOLs and BOOGLs rarely communicate horizontally and, even more rarely, downward to the DICforce, Wikis are a curse because….

Networks make organizational culture and politics explicit. – Michael Schrage

BOOGLs and SCOLs that preside over malevolent CCHs don’t like having their day-to-day operational behavior exposed to the light of day. If a malevolent CCH org is liberal enough to “approve” of Wiki usage, chances are that none of the BOOGLs or SCOLs will contribute to its content. In the worse case, a Wiki police force may be established to enforce posting rules designed to keep politics and positioning behavior secret. Hell, without censorship, the DICforce might form the opinion that they are being led by a gang of thugs who are out for themselves instead of the lasting well being of the org.

Are you here to build a career or to build an organization? – Peter Block

Exaggerated And Distorted

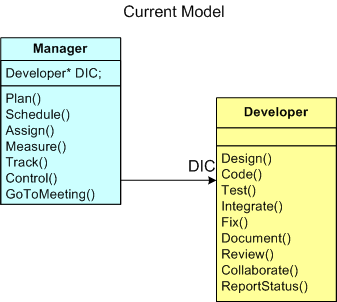

The figure below provides a UML class diagram (“class” is such an appropriate word for this blarticle) model of the Manager-Developer relationship in most software development orgs around the globe. The model is so ubiquitous that you can replace the “Developer” class with a more generic “Knowledge Worker” class. Only the Code(), Test(), and Integrate() behaviors in the “Developer” class need to be modified for increased global applicability.

Everyone knows that this current model of developing software leads to schedule and cost overruns. The bigger the project, the bigger the overruns. D’oh!

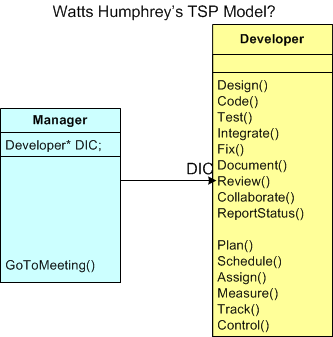

In this article and this interview, Watts Humphrey trumps up his Team Software Process (TSP) as the cure for the disease. The figure below depicts an exaggerated and distorted model of the manger-developer relationship in Watts’s TSP. Of course, it’s an exaggerated and distorted view because it sprang forth from my twisted and tortured mind. Watts says, and I wholeheartedly agree (I really do!), that the only way to fix the dysfunction bred by the current way of doing things is to push the management activities out of the Manager class and down into the Developer class (can you say “empowerment”, sic?). But wait. What’s wrong with this picture? Is it so distorted and exaggerated that there’s not one grain of truth in it? Decide for yourself.

Even if my model is “corrected” by Watts himself so that the Manager class actually adds value to the revolutionary TSP-based system, do you think it’s pragmatically workable in any org structured as a CCH? Besides reallocating the control tasks from Manager to Developer, is there anything that needs to socially change for the new system to have a chance of decreasing schedule and cost overruns (hint: reallocation of stature and respect)? What about the reward and compensation system? Does that need to change (hint: increased workload/responsibility on one side and decreased workload/responsibility on the other)? How many orgs do you know of that aren’t structured as a crystalized CCH?

Strangely (or not?), Watts doesn’t seem to address these social system implications of his TSP. Maybe he does, but I just haven’t seen his explanations.

Three Types

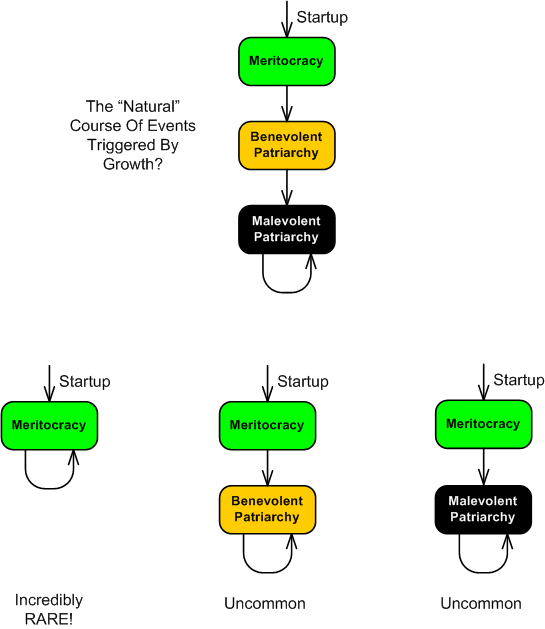

One simple (simplistic?) way of looking at how orgs of people operate is by classifying them into three abstract types:

- The Malevolent Patriarchy

- The Benevolent Patriarchy

- The Meritocracy

Since it’s so uncommon and rare to find a non-patriarchically run org (which is so pervasive that the genre includes small, husband-wife-children, families like yours and mine), I struggled with concocting the name of the third type. Got a better name?

The figure below shows a highly unscientific family of maturation trajectories that an org can take after “startup”. The ubiquitous, well worn path that is tread as an org grows in size is the Meritocracy->Benevolent Patriarchy->Malevolent Patriarchy sojourn. Note that there are no reverse transitions in any of the trajectories. That’s because reverse state changes, like a Benevolent Patriarchy-to-Meritocracy transformation, are as rare as a company remaining in the Meritocracy state throughout its lifetime.

The state versus time graph below communicates the same information as the state machine family above, but from a time-centric viewpoint. Since “all models are wrong, but some are useful” (George Box), the instantaneous transition points, T1 and T2, are wrong. These insidious transitions occur so gradually and so slooowly that no one, not even the So-Called Org Leadership (SCOL), notices a state change. Bummer, no?

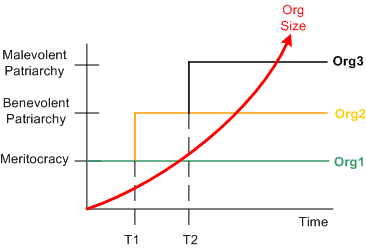

PAYGO II

PAYGO stands for “Pay As You Go“. It’s the name of the personal process that I use to create or maintain software. There are five operational states in PAYGO:

- Design A Little

- Code A Little

- Test A Little

- Document A Little

- Done For Now

Yes, the fourth state is called “Document A Little“, and it’s a first class citizen in the PAYGO process. Whatever process you use, if some sort of documentation activity is not an integral part of it, then you might be an incomplete and one dimensional engineer, no?

“…documentation is a love letter that you write to your future self.” – Damian Conway

The UML state transition diagram below models the PAYGO states of operation along with the transitions between them. Even though the diagram indicates that the initial entry into the cyclical and iterative PAYGO process lands on the “Design A Little” state of activity, any state can be the point of entry into the process. Once you’re immersed in the process, you don’t kick out into the “Done For Now” state until your first successful product handoff occurs. Here, successful means that the receiver of your work, be it an end user or a tester or another programmer, is happy with the result. How do you know when that is the case? Simply ask the receiver.

Notice the plethora of transition arcs in the diagram (the green ones are intended to annotate feedback learning loops as opposed to sequential forward movements). Any state can transition into any other state and there is no fixed, well defined set of conditions that need to be satisfied before making any state-to-state leap. The process is fully under your control and you freely choose to move from state to state as “God” (for lack of a better word) uses you as an instrument of creation. If clueless STSJ PWCE BMs issue mindless commands from on high like “pens down” and “no more bug fixing, you’re only allowed to write new code“, you fake it as best you can to avoid punishment and you go where your spirit takes you. If you get caught faking it and get fired, then uh….. soothe your conscience by blaming me.

The following quote in “The C++ Programming Language” by mentor-from-afar Bjarne Stroustrup triggered this blog post:

In the early years, there was no C++ paper design; design, documentation, and implementation went on simultaneously. There was no “C++ project” either, or a “C++ design committee.” Throughout, C++ evolved to cope with problems encountered by users and as a result of discussions between my friends, my colleagues, and me. – Bjarne Stroustrup

When I read it on my Nth excursion through the book (you’ve made multiple trips through the BS book too, no?), it occurred to me that my man Bjarne uses PAYGO too.

Say STFU to all the mindlessly mechanistic processes from highly-credentialed and well-intentioned luminaries like Watts Humphrey’s PSP (because he wants to transform you into an accountant) and your mandated committee corpo process group (because the chances are that the dudes who wrote the process manuals haven’t written software in decades) and the TDD know-it-alls. Embrace what you discover is the best personal development process for you; be it PAYGO or whatever personal process the universe compels you to embrace. Out of curiosity, what process do you use?

If you’re interested in a higher level overview of the personal PAYGO process in the context of other development processes, you can check out this previous post: PAYGO I. And thanks for listening.

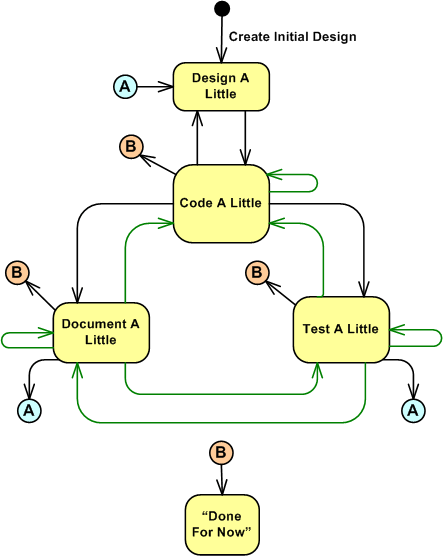

Viable, Vulnerable, Doomed II

As the title indicates, this blow-sst is an extension of yesterday’s inane blabberfest. While yesterday’s lesson (<— lol!) dealt with the static structure of Viable, Vulnerable, and Doomed (VVD) orgs, today’s BS-fest talks about the dynamic behavior of VVD social groups. Behold that if you’re conscious and you concentrate on observing the world around you, the structure plus behavior of an org will clearly and unambiguously reveal over time what it does. Forget what its so-called leaders say it does, observe for yourself how the stratified monolith is structured, how it behaves, and what it actually produces. If you’re diligent and astute, you’ll discover the principle of POSIWID: the Purpose Of a System Is What It Does (not what it’s leadership says it does).

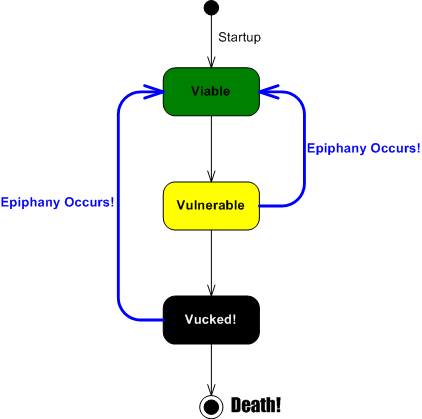

The UML diagram below shows a state machine model of: the mutually exclusive states of a VVV system, the transitions between the states, and the events that trigger the transitions. But wait…… VVV? What happened to VVD? Well, in a dumbass attempt to inject levity and fruitlessly retain your interest, I changed the name of the “Doomed” state to “”Vucked” so that all states start with the letter “V”. Stupid, no?

Virtually all startup companies initialize into the viable state. After all, if they didn’t have a product or service that a market didn’t want to consume, they wouldn’t be born as a viable entity, right? Over time, if they neglect their explorers and single mindedly, greedily, milk their product/service to death, eventually they’d become vulnerable to competitors. If the leadership becomes drunk with success and their heads expand too far, they start resenting and rejecting their explorers – they become vucked!

Unless, as the figure below shows, an epiphany in the head shed occurs (and the chances of that occurring in fat headed executives rolling in dough are incredibly slim) it’s death to the org and all its membership – including the innocents who had no hand in the implosion. This ain’t a hollywood story so there’s no happy ending.