Archive

Myopia And Hyperopia

Assume that we’ve just finished designing, testing, and integrating the system below:

Now let’s zoom in on the “as-built“, four class, design of SS2 (SubSystem 2). Assume its physical source tree is laid out as follows:

Given this design data after the fact, some questions may come to mind: How did the four class design cluster come into being? Did the design emerge first, the production code second, and the unit tests come third in a neat and orderly fashion? Did the tests come first and the design emerge second? Who gives a sh-t what the order and linearity of creation was, and perhaps more importantly, why would someone give a sh-t?

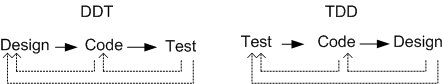

It seems that the TDD community thinks the way a design manifests is of supreme concern. You see, some hard core TDD zealots think that designing and writing the test code first ala a strict “red-green-refactor” personal process guarantees a “better” final design than any other way. And damn it, if you don’t do TDD, you’re a second class citizen.

BD00 thinks that as long as refactoring feedback loops exist between the designing-coding-testing efforts, it really doesn’t freakin’ matter which is the cart and which is the horse, nor even which comes first. TDD starts with a local, myopic view and iteratively moves upward towards global abstraction. DDT (Design Driven Test) starts with a global, hyperopic view and iteratively moves downward towards local implementation. A chaotic, hybrid, myopia-hyperopia approach starts anywhere and jumps back and forth as the developer sees fit. It’s all about the freedom to choose what’s best in the moment for you.

Notice that TDD says nothing about how the purely abstract, higher level, three-subsystem cluster (especially the inter-subsystem interfaces) that comprise the “finished” system should come into being. Perhaps the TDD community can (should?) concoct and mandate a new and hip personal process to cover software system level design?

Parallelism And Concurrency

In the beginning of Robert Virding’s brilliant InfoQ talk on Erlang, he distinguishes between parallelism and concurrency. Parallelism is “physical“, having to do with the static number of cores and processors in a system. Concurrency is “abstract“, having to do with the number of dynamic application processes and threads running in the system. To relate the physical with the abstract, I felt compelled to draw this physical-multi-core, physical-multi-node, abstract-multi-process, abstract-multi-thread diagram:

It’s not much different than the pic in this four year old post: PTCPN. It’s simply a less detailed, alternative point of view.

Stuck And Bother

I’m currently working on a project with a real, hard deadline. My team has to demonstrate a working, multi-million dollar radar in the near future to a potential deep-pocketed customer. As you can see below, the tower is up and the antenna is majestically perched on its pedestal. However, it ain’t spinning yet. Nor is it radiating energy, detecting signal returns, or extracting/estimating target information (range, speed, angle, size) buried in a mess of clutter and noise. But of course, we’re integrating the hardware and software and progressing toward the goal.

Lest you think otherwise, I’m no Ed Snowden and those pics aren’t classified. If you’re a radar nerd, you can even get this particular radar emblazoned on a god-awful t-shirt (like I did) from zazzle.com:

OK, enough of this bulldozarian levity. Let’s get serious again – oooh!

As a hard deadline approaches on a project, a perplexing question always comes to my mind:

How much time should I spend helping others who get “stuck“, versus getting the code I am responsible for writing done in time for the demo? And conversely, when I get stuck, how often should I “bother” someone who’s trying to get her own work done on time?

Of course, if you’re doing “agile“, situations like this never happen. In fact, I haven’t ever seen or heard a single agile big-wig address this thorny social issue. But reality being what it is, situations like this do indeed happen. I speculate that they happen more often than not – regardless of which methodology, practices, or tools you’re using. In fact, “agile” has the potential to amplify the dilemma by triggering the issue to surface on a per sprint basis.

Save for the psychopaths among us, we all want to be altruistic simply because it’s the culturally right thing to do. But each one of us, although we’re sometimes loathe to admit it, has been endowed by mother nature with “the selfish gene“. We want to serve ourselves and our families first. In addition, the situation is exacerbated by the fact that the vast majority of organizations unthinkingly have dumb-ass recognition and reward systems in place that celebrate individual performance over team performance – all the while assuming that the latter is a natural consequence of the former. Life can be a be-otch, no?

On Complexity And Goodness

While browsing around on Amazon.com for more books to read on simplicity/complexity, the pleasant memory of reading Dan Ward’s terrific little book, “The Simplicity Cycle“, somehow popped into my head. Since it has been 10 years since I read it, I decided to dig it up and re-read it.

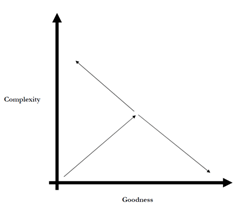

In his little gem, Dan explores the relationships between complexity, goodness, and time. He starts out by showing this little graph, and then he spends the rest of the book eloquently explaining movements through the complexity-goodness space.

First things first. Let’s look at Mr. Ward’s parsimonious definitions of system complexity and goodness:

Complexity: Consisting of interconnected parts. Lots of interconnected parts equal high degree of complexity. Few interconnected parts equal a low degree of complexity.

Goodness: Operational functionality or utility or understandability or design maturity or beauty.

Granted, these definitions are just about as abstract as we can imagine, but (always) remember that context is everything:

The number 100 is intrinsically neither large nor small. 100 interconnected parts is a lot if we’re talking about a pencil sharpener, but few if we’re talking about a jet aircraft. – Dan Ward

When we start designing a system, we have no parts, no complexity (save for that in our heads), no goodness. Thus, we begin our effort close to the origin in the complexity-goodness space.

As we iteratively design/build our system, we conceive of parts and we connect them together, adding more parts as we continuously discover, learn, employ our knowledge of, and apply our design expertise to the problem at hand. Thus, we start moving out from the origin, increasing the complexity and (hopefully!) goodness of our baby as we go. The skills we apply at this stage of development are “learning and genesis“.

At a certain point in time during our effort, we hit a wall. The “increasing complexity increases goodness” relationship insidiously morphs into an “increasing complexity decreases goodness” relationship. We start veering off to the left in the complexity-goodness space:

Many designers, perhaps most, don’t realize they’ve rotated the vector to the left. We continue adding complexity without realizing we’re decreasing goodness.

We can often justify adding new parts independently, but each exists within the context of a larger system. We need to take a system level perspective when determining whether a component increases or decreases goodness. – Dan Ward

Once we hit the invisible but surely present wall, the only way to further increase goodness is to somehow start reducing complexity. We can do this by putting our “learning and genesis” skills on the shelf and switching over to our vastly underutilized “unlearning and synthesis” skills. Instead of creating and adding new parts, we need to reduce the part count by integrating some of the parts and discarding others that aren’t pulling their weight.

Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but rather when there is nothing more to take away. – Antoine de Saint Exupery

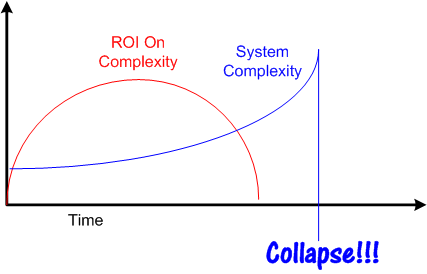

Dan’s explanation of the complexity-goodness dynamic is consistent with Joseph Tainter’s account in “The Collapse Of Complex Societies“. Mr. Tainter’s thesis is that as societies grow, they prosper by investing in, and adding layer upon layer, of complexity to the system. However, there is an often unseen downside at work during the process. Over time, the Return On Investment (ROI) in complexity starts to decrease in accordance with the law of diminishing returns. Eventually, further investment depletes the treasury while injecting more and more complexity into the system without adding commensurate “goodness“. The society becomes vulnerable to a “black swan” event, and when the swan paddles onto the scene, there are not enough resources left to recover from the calamity. It’s collapse city.

The only way out of the runaway increasing complexity dilemma is for the system’s stewards to conscientiously start reducing the tangled mess of complexity: integrating overlapping parts, fusing tightly coupled structures, and removing useless or no-longer-useful elements. However, since the biggest benefactors of increasing complexity are the stewards of the system themselves, the likelihood of an intervention taking place before a black swan’s arrival on the scene is low.

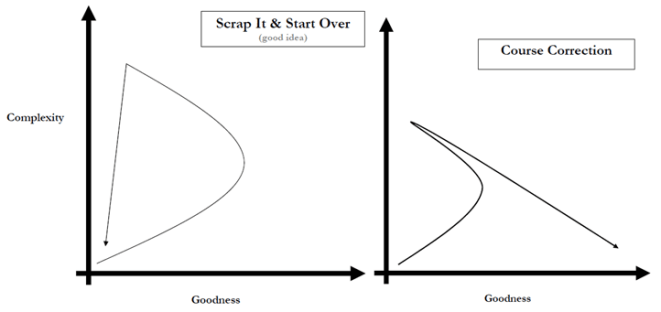

At the end of his book, Mr. Ward presents a few patterns of activity in the complexity-goodness space, two of which align with Mr. Tainter’s theory. Perhaps the one on the left should be renamed “Collapse“?

So, what does all this made up BD00 complexity-goodness-collapse crap mean to me in my little world (and perhaps you)? In my work as a software developer, when my intuition starts whispering in my ear that my architecture/sub-designs/code are starting to exceed my capacity to understand the product, I fight the urge to ignore it. I listen to that voice and do my best to suppress the mighty, culturally inculcated urge to over-learn, over-create, and over-complexify. I grudgingly bench my “learning and genesis” skills and put my “unlearning and synthesis” skills in the game.

An Intimate Act Of Communication

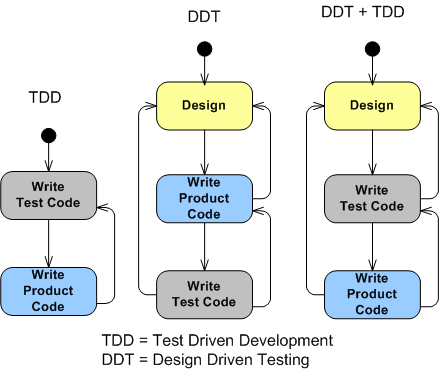

Take a look at these three state machine models for intimately developing a chunk of functionally cohesive software:

The key distinguishing feature of the two machines on the right from the pure TDD machine on the left is that some level of design is the initial driver, informer, of the subsequent coding/testing development process. Note that all three methods contain feedback transitions triggered by “learning as we go” events.

In my understanding of TDD, no time is “wasted” upfront thinking about, or capturing, design data at any level of granularity. The pithy mandate from the TDD gods is “red-green-refactor” or die. The design bubbles up solely from the testing/coding cycle in a zen-like flow of intelligence.

Personally, I work in accordance with the DDT model. How about you? For newbies who were solely taught, and only know how to do, TDD, have you ever thought about trying the “traditional” DDT way?

BTW, I learned, tried, and then rejected, TDD as my personal process from “Unit Test Frameworks“. Except for the parts on TDD, it’s a terrific book for learning about unit testing.

Since “design” is an intimately personal process, whatever works for you is fine by BD00. But just because it’s “newer” and has a lot of rabid fan-boys promoting it (including some big and famous consultants), don’t auto-assume TDD is da bomb.

Design is an intimate act of communication between the creator and the created. – Unknown

From #NoProjects To #NoOrganization

Let’s jump on the twitter #NoProjects bandwagon and see where it takes our organization….

Many thanks to Gene Hughson for the #NoCustomers idea that fueled the writing of this post.

A Skeptical “No”

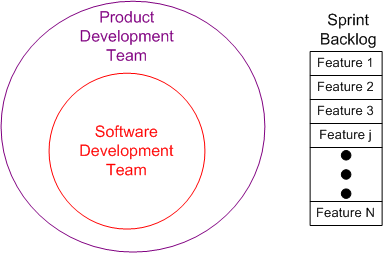

Just about every agile video, book, and article I’ve ever consumed assumes some variant of the underlying team model shown below. The product these types of teams build is comprised of custom software running on off-the-shelf server hardware. Even though it’s not shown, they also assume a client-server structure, request-response protocol, database-centric system.

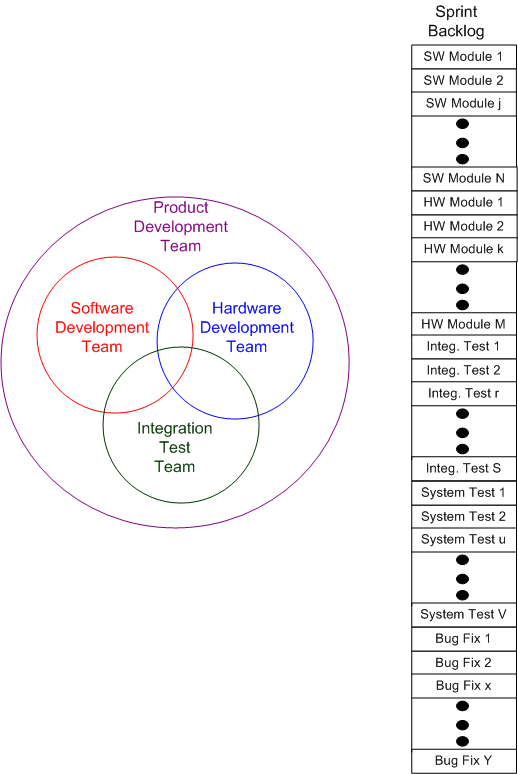

The team model for the types of systems I work on is given below. They are distributed real-time event systems comprised of embedded, heterogeneous, peer processors glued together via a pub-sub protocol. By necessity, specialized, multi-disciplinary teams are required to develop this category of systems. Also, by necessity, the content of the sprint backlog is more complex and intricately subtler than the typical agile IT product backlog of “features” and “user stories“.

When I watch/read/listen to smug agile process experts and coaches expound the virtues of their favorite methodology using narrow, anecdotal, personal stories from the database-centric IT world, I continuously ask myself “can this apply to the type of products I help build?“. Often, the answer is a skeptical “no“. Not always, but often.

Result-Focused, Or State-Focused?

As I continue to explore/evaluate the relevance of the SEMAT Kernel to the future of software engineering, I’m finding that I’m liking it less and less. (For a quick introduction to the SEMAT Kernel, please go read this post, “Revolution, Or Malarkey?“, and then return back here if you’re still interested in what BD00 has to say.)

One of the principal creators of the SEMAT movement, Ivar Jacobson, subjectively asserts that:

“…using the SEMAT kernel to drive team behavior makes the team result focused instead of document driven or activity centric.” – Ivar Jacobson

Using the patented BD00 method of distorted analysis, let’s explore this bold proclamation further.

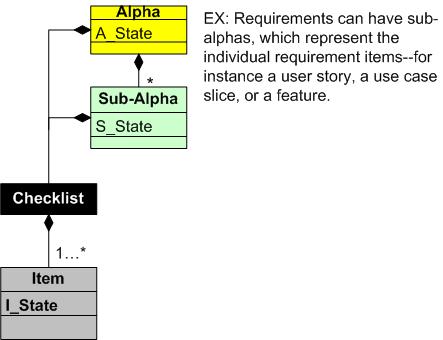

In the current definition of the SEMAT kernel, each of the seven top-level alphas in the SEMAT Kernel has a state whose value at any given moment is determined by the sub-states of a set of criteria items in a checklist. In addition, each sub-alpha itself has a checklist-determined state.

“Each state has a checklist that specifies the criteria needed to reach the state. It is these states that make the kernel actionable and enable it to guide the behavior of software development teams.” – “The Essence Of Software Engineering“

So, let’s look at some numbers for a small, hypothetical, SEMAT-based project. Assume the following definition of our project:

- 7 Alphas

- Each alpha has 3 Sub-Alphas

- Each checklist has 5 Items

With these metrics characterizing our project, we need to continuously track/update:

- 7 alpha states

- 7 * 3 = 21 Sub-alpha states

- 7 * 3 * 5 = 105 checklist item states

Man, that’s a lotto states for our relatively small, 21 sub-alpha project, no? It seems like the SEMAT team could be spending a lot of time in a state of confusion updating the checklist document(s) that dynamically track the state values. Thus,

“…using the SEMAT kernel to drive team behavior makes the team state focused instead of result focused.” – BD00

Unless result == state, Ivar may be mistaken.

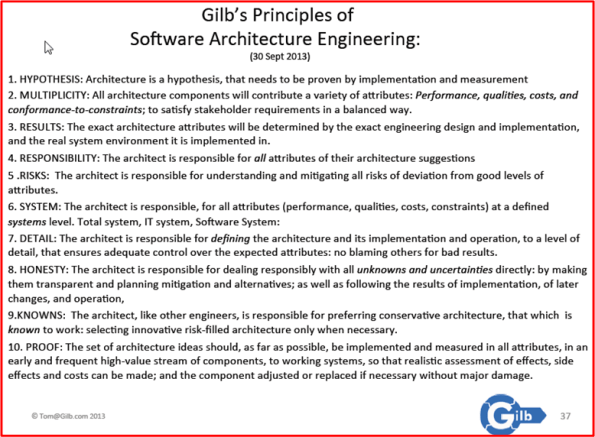

Gilbitecture

Plucked from his deliciously titled “Real Architecture: Engineering or Pompous Bullshit?” slide deck, I give you Tom Gilb‘s personal principles of software architecture engineering:

Tom’s proactive approach seems like a far cry from the reactive approaches of the “emergent architecture” and TDA (Test Driven Architecture) communities, doesn’t it?

OMG! Tom’s list actually uses the words “engineering” and “the architect“. Maybe that’s why I have always appreciated his work so much. 🙂