Archive

Find The Bug

The part of the conclusion in the green box below for 32 bit linux/GCC (g++) is wrong. A “long long” type is 64 bits wide for that platform combo. If you can read the small and blurry text in the dang thing, can you find the simple logical bug in the five line program that caused the erroneous declaration? And yes, it was the infallible BD00 who made this mess.

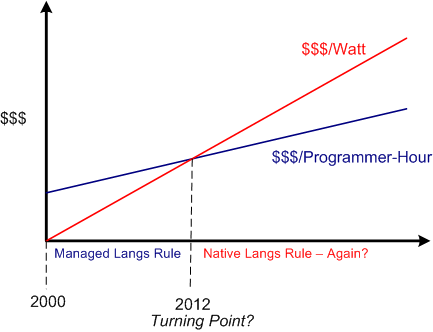

Performance Per Watt

Recently, I concocted a blog post on Herb Sutter‘s assertion that native languages are making a comeback due to power costs usurping programming labor costs as the dominant financial drain in software development. It seems that the writer of this InforWorld post seems to agree:

But now that Intel has decided to focus on performance per watt, as opposed to pure computational performance, it’s a very different ball game. – Bill Snyder

Since hardware developers like Intel have shifted their development focus towards performance per watt, do you think software development orgs will follow by shifting from managed languages (where the minimization of labor costs is king) to native languages (where the minimization of CPU and memory usage is king)?

Hell, I heard Facebook chief research scientist Andrei Alexandrescu (admittedly a native language advocate (C++ and D)) mention the never-used-before “users per watt” metric in a recent interview. So, maybe some companies are already onboard with this “paradigm shift“?

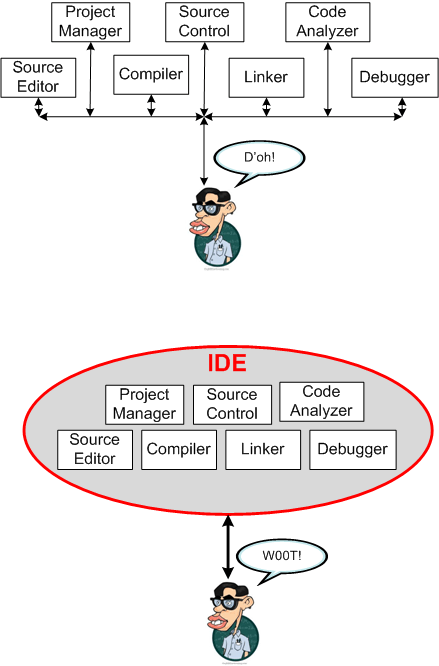

The IDEs Of March

I’m an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) man. I like the way IDEs (Eclipse, Visual Studio) provide an overarching dashboard overview and uniform control over the tool set needed to build software. Plus, I’m horrible at remembering commands; and as I get older, it gets worse.

How about you? Are you an IDE user or a command line person?

D4P4D

I just received two copies of William Livingston’s “Design For Prevention For Dummies” (D4P4D) gratis from the author himself. It’s actually section 7 of the “Non-Dummies” version of the book. With the addition of “For Dummies” to the title, I think it was written explicitly for me. D’oh!

The D4P is a mind bending, control theory based methodology (think feedback loops) for problem prevention in the midst of powerful, natural institutional forces that depend on problem manifestation and continued presence in order to keep the institution alive.

Mr. Livingston is an elegant, Shakespearian-type writer who’s fun to read but tough as hell to understand. I’ve enjoyed consuming his work for over 25 years but I still can’t understand or apply much of what he says – if anything!

As I slowly plod through the richly dense tome, I’ll try to write more posts that disclose the details of the D4P process. If you don’t see anything more about the D4P from me in the future, then you can assume that I’ve drowned in an ocean of confusion.

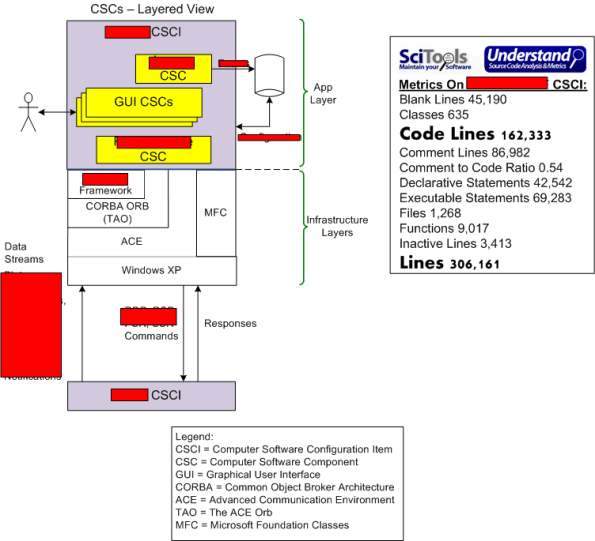

Starting Point

Unless you’re an extremely lucky programmer or you work in academia, you’ll spend most of your career maintaining pre-existing, revenue generating software for your company. If your company has multiple products and you don’t choose to stay with one for your whole career, then you’ll also be hopping from one product to another (which is a good thing for broadening your perspective and experience base – so do it).

For your viewing pleasure, I’ve sketched out the structure and provided some code-level metrics on the software-intensive product that I recently started working on. Of course, certain portions of the graphic have been redacted for what I hope are obvious reasons.

How about you? What does your latest project look like?

The Old Is New Again

Because Moore’s law has seemingly run its course, vertical, single processor core speed scaling has given way to horizontal multicore scaling. The evidence of this shift is the fact that just about every mobile device and server and desktop and laptop is shipping with more than one processor core these days. Thus, the acquisition of concurrent and distributed design and programming skills is becoming more and more important as time tics forward. Can what Erlang’s Joe Armstrong coined as the “Concurrent Oriented Programming” style be usurping the well known and widely practiced object-oriented programming style as we speak?

Because of their focus on stateless, pure functions (as opposed to stateful objects), it seems to me that functional programming languages (e.g. Erlang, Haskell, Scala, F#) are a more natural fit to concurrent, distributed, software-intensive systems development than object-oriented languages like Java and C++; even though both these languages provide basic support for concurrent programming in the form of threads.

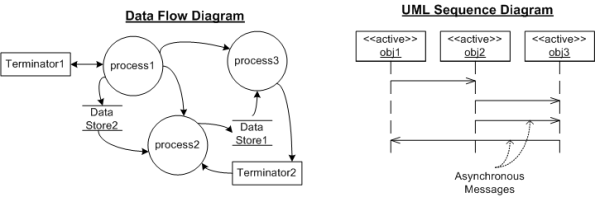

Likewise, even though I’m a big UML fan, I think that “old and obsolete” structured design modeling tools like Data and Control Flow Diagrams (DFD, CFD) may be better suited to the design of concurrent software. Even better, I think a mixture of the UML and DFD/CFD artifacts may be the best way (as Grady Booch says) to “visualize and reason” about necessarily big software designs prior to coding up and testing the beasts.

So, what do you think? Should the old become new again? Should the venerable DFD be resurrected and included in the UML portfolio of behavior diagrams?

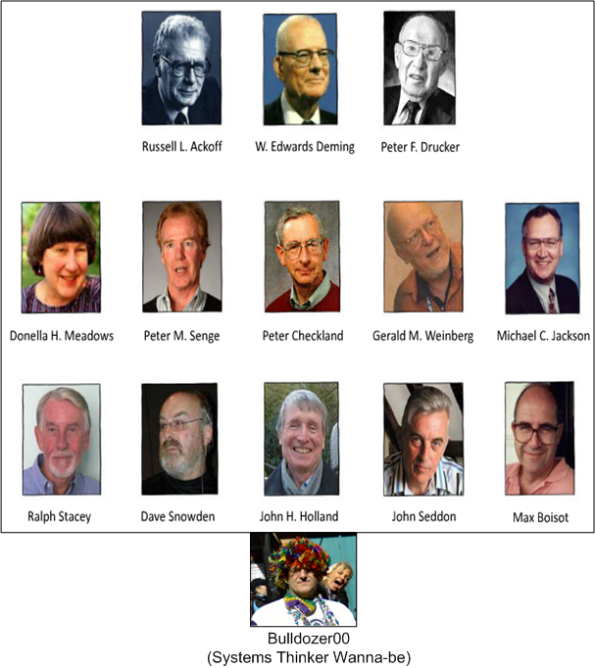

Roster Of System Thinkers

Someone on Twitter, I can’t remember who, tipped me off to a terrific “Complexity Thinking” Slideshare deck. I felt the need to snip out this slide of system thinkers and complexity researchers to share with you:

So far, I’ve read some of the work of Ackoff (my fave), Deming, Drucker, Meadows, Senge, Weinberg, and Jackson. In addition, I’ve studied the work of “fringe” system thinkers Rudy Starkermann, John Warfield, Bill Livingston, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Thorstein Veblen, Ross Ashby, Stafford Beer, and Norby Wiener.

I look forward to discovering what the others on the roster have to say.

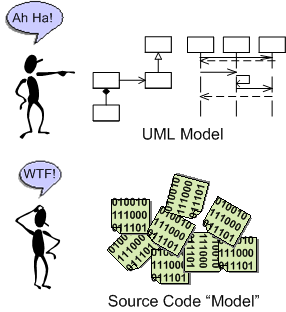

Visualizing And Reasoning About

I recently read an interview with Grady Booch in which the interviewer asked him what his proudest technical achievement was. Grady stated that it was his involvement in the creation of the Unified Modeling Language (UML). Mr. Booch said it allowed for a standardized way (vs. ad-hoc) of “visualizing and reasoning about software” before, during, and/or after its development.

How To, When To

It seems like someone at USA Today has been ingesting contraband. In “Stereotype of computer geeks fades and nerds are cool”, Haya El Nasser opines:

The stereotype of the geeky techie that persists in pop culture is fading in real life, thanks to the legacy of industry giants such as Apple founder Steve Jobs and the increasing dependence of more Americans on the skills of those who know how to make their gadgets work.

Some schools are offering one-day workshops that include tips on “office finesse” and wardrobe and body language and when to talk or when to pick up a dropped napkin when meeting with a prospective employer.

When to pick up a dropped napkin when meeting with a prospective employer? WTF! How about tips on:

- When it’s appropriate to tie your bib at the dinner table.

- When to clip your nose hairs.

- How long to wait before acting on a “there’s free leftover food in the conference room” e-mail.

- How often to apply deodorant

- How to emulate a British accent

- How to eat cake at a going away party

- When to clap at an all hands meeting

- How many breaths to breathe before hitting the “send-all” button

- How not to pile your plate sky high at free lunches

- How to snicker without getting caught

- How to detect tattletalers

- How to carry your coffee cup like Wally

- How to respond to the “what percent done are you?” question

- When you can skip washing your hands in the rest room

- How long to wait before consuming that seemingly forgotten lunch in the fridge

- When to be fashionably late to meetings

- How to wordsmith inappropriate questions to the company help desk into benign pleas for help

- How to <<insert your intractable issue here>>

All Forked Up!

BD00 posits that many software development orgs start out with good business intentions to build and share a domain-specific “platform” (a.k.a. infrastructure) layer of software amongst a portfolio of closely related, but slightly different instantiations of revenue generating applications. However, as your intuition may be hinting at, the vast majority of these poor souls unintentionally, but surely, fork it all up. D’oh!

The example timeline below exposes just one way in which these colossal “fork ups” manifest. At T0, the platform team starts building the infrastructure code (common functionality such as inter-component communication protocols, event logging, data recording, system fault detection/handling, etc) in cohabitation with the team of the first revenue generating app. It’s important to have two loosely-coupled teams in action so that the platform stays generic and doesn’t get fused/baked together with the initial app product.

At T1, a new development effort starts on App2. The freshly formed App2 team saves a bunch of development cost and time upfront by reusing, as-is, the “general” platform code that’s being co-evolved with App1.

Everything moves along in parallel, hunky dory fashion until something strange happens. At T2, the App2 product team notices that each successive platform update breaks their code. They also notice that their feature requests and bug reports are taking a back seat to the App1 team’s needs. Because of this lack of “service“, at T3 the frustrated App2 team says “FORK IT!” – and they literally do it. They “clone and own” the so-called common platform code base and start evolving their “forked up” version themselves. Since the App2 team now has to evolve both their App and their newly born platform layer, their schedule starts slipping more than usual and their prescriptive “plan” gets more disconnected from reality than it normally does. To add insult to injury, the App2 team finds that there is no usable platform API documentation, no tutorial/example code, and they must pour through 1000s of lines of code to figure out how to use, debug, and add features to the dang thing. Development of the platform starts taking more time than the development of their App and… yada, yada, yada. You can write the rest of the story, no?

So, assume that you’ve been burned once (and hopefully only once) by the ubiquitous and pervasive “forked up” pattern of reuse. How do you prevent history from repeating itself (yet again)? Do you issue coercive threats to conform to the mission? Do you swap out individuals or whole teams? Do you send your whole org to a 3 day Scrum certification class? Will continuous exhortations from the heavens work to change “mindsets“? Do you start measuring/collecting/evaluating some new metrics? Do you change the structure and behaviors of the enclosing social system? Is this solely a social problem; solely a technical problem? Do you not think about it and hope for the best – the next time around?