Archive

Out Of One, Many

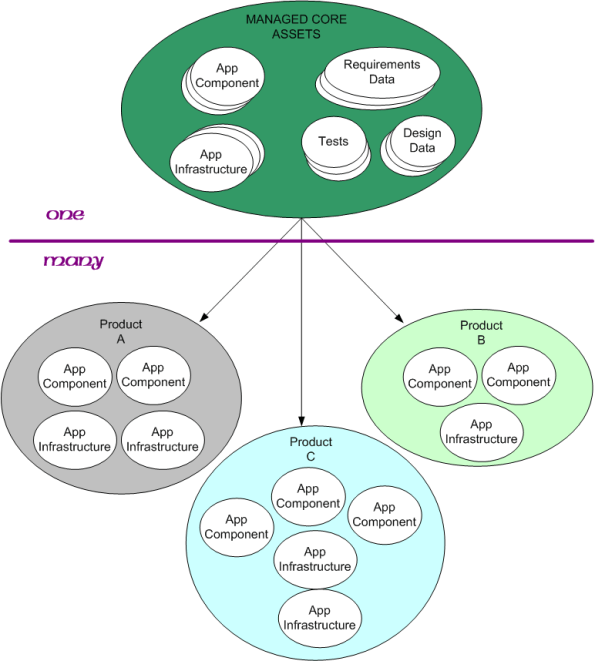

A Software Product Line (SPL) can be defined as “a set of software-intensive systems that share a common, managed set of features satisfying the specific needs of a particular market segment or mission and that are developed from a common set of core assets in a prescribed way“.

The keys to developing and exploiting the value of an SPL are

- specifying the interfaces and protocols between app components and infrastructure components

- the granularity of the software components: 10-20K lines of code,

- the product instantiation and test process,

- the disciplined management of changes to the app and infrastructure components.

- managing obsolescence of open source components/libs used in the architecture

- keeping the requirements and design data in synch with the code base

Any others?

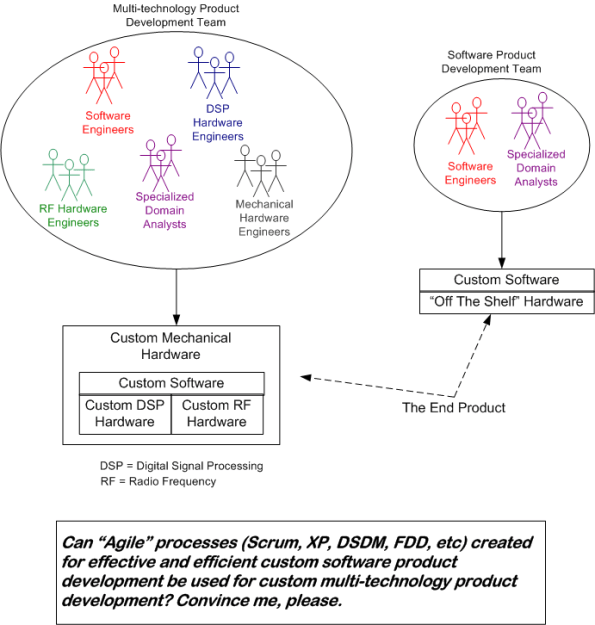

Still Applicable Today

Note: This graphic was clipped out of Bill Livingston’s D4P4D.

Two Plus Months

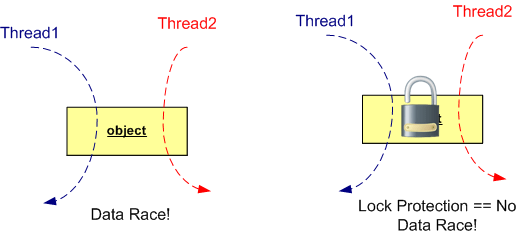

Race conditions are one of the worst plagues of concurrent code: They can cause disastrous effects all the way up to undefined behavior and random code execution, yet they’re hard to discover reliably during testing, hard to reproduce when they do occur, and the icing on the cake is that we have immature and inadequate race detection and prevention tool support available today. – Herb Sutter (DrDobbs.com)

With this opening paragraph in mind, observe the figure below. If you don’t lock-protect a stateful object that’s accessed by more than one thread, you’re guaranteed to fall into the dastardly trap that Herb describes. D’oh!

Now, look at the two object figure below. Unless you protect each of the two objects in the execution path with a lock, you’re hosed!

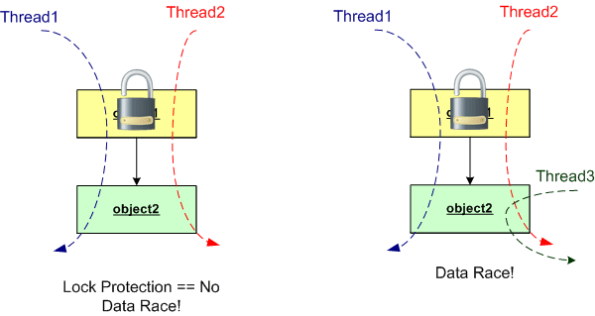

To improve performance at the expense of higher risk, you can use one lock for the two object example like on the left side of this graphic:

Alas, if you do choose to use one lock in a two object configuration like the example above, you better be sure that you don’t come in through the side with another thread to use the thread-unsafe object2. You also better be sure that a future maintainer of your code doesn’t do the same. But wait… How can you ensure that a maintainer won’t do that? You can’t. So stick with the more conservative, lower performance, one-lock-per-object approach.

Don’t ask me why I wrote this post cuz I ain’t answering. Well, Ok, ask. I wrote this post because I was burned by the left-hand side of the second graphic in this post. It took quite awhile, actually two plus months, to finally localize and squash the bugger in production code. As usual, Herb was right.

And please, don’t tell me that lock-free programming is the answer:

…replacing locks wholesale by writing your own lock-free code is not the answer. Lock-free code has two major drawbacks. First, it’s not broadly useful for solving typical problems—lots of basic data structures, even doubly linked lists, still have no known lock-free implementations. Second, it’s hard even for experts. It’s easy to write lock-free code that appears to work, but it’s very difficult to write lock-free code that is correct and performs well. Even good magazines and refereed journals have published a substantial amount of lock-free code that was actually broken in subtle ways and needed correction. – Herb Sutter (Dr. Dobbs).

Not Applicable?

No Lessons Learned II

Since my post on the JTRS fiasco generated more blog traffic than usual, this post is based on the same theme – the failure of a big, multi-techonology, socio-technical project. Today’s topic is the termination of the Army’s massive Future Combat Systems (FCS) program in 2009 after 6 years of development and gobs of spent taxpayer money. Actually, some face-saving was achieved on this boondoggle since the monolithic FCS program was replaced by several smaller, fragmented programs.

From a slew of pages I bookmarked on Delicious.com over the years, I pieced together the following timeline of events for the FCS program.

1) The FCS program is formally kicked off in 2003, with much fanfare, of course.

2) In August 2005, the program met 100% of the criteria in its most important milestone to date, Systems of Systems Functional Review. (Whoo Hoo, the “paper” docs were perfect!)

3) January 24, 2008. Congressional investigators express “concern” that the lines of code have nearly doubled since development began in 2003. And they question the Army’s oversight of a far-flung project involving more than 2,000 developers and dozens of contractors working across the nation. The Government Accountability Office, Congress’s watchdog, says the Army underestimated the undertaking. When the software project began, investigators say the Army estimated it needed 33.7 million lines of code; it’s now 63.8 million — about three times the number for the Joint Strike Fighter aircraft program. The software program “started prematurely. They didn’t have a solid knowledge base,” said Bill Graveline, a GAO official involved in the government’s ongoing review. “They didn’t really understand the requirements.”

4) Mar 18, 2008. Setbacks in the Army’s development of its software requirements for FCS due to the immaturity of the program and the aggressive pace of the Army’s development schedule, however, have led to delays, errors and omissions in the development of essential software packages for the program, while flaws in those packages have in turn delayed or threatened other development efforts, GAO said. Developers for five major software packages, for example, said that the high-level requirements they received from the Army were poorly defined, late or missing during the development process, GAO said.

5) June 13, 2008. Possible budget cuts, a change of administration and the Pentagon’s focus on supporting operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have ratcheted up pressure on the program just when it is showing tangible signs of progress after five years of work and almost $15 billion in taxpayer money invested.

6) Mar 02, 2009 The systems integrators heading the Army’s Future Combat Systems program have confirmed that development of the hardware and software required for the program’s vehicles and weapons systems is proceeding as planned. (Boeing Co. and Science Applications International Corp. are the lead systems integrators for the $87 billion FCS program.)

7) June 23, 2009. The memorandum issued confirms the recommendations made earlier this year by Defense Secretary Robert Gates to replace the single, giant program with a number of smaller modernization efforts.

FCS, particularly the manned combat vehicle portion, did not reflect the anti-insurgency lessons learned in Iraq and Afghanistan. – Robert Gates

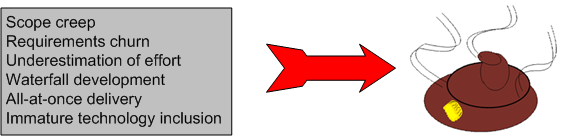

So, let’s see what went wrong: ambiguous and inconsistent and misunderstood requirements, gross underestimation of effort, immature technologies, “aggressive” schedules. Sound familiar? Yawn. Same old, same old.

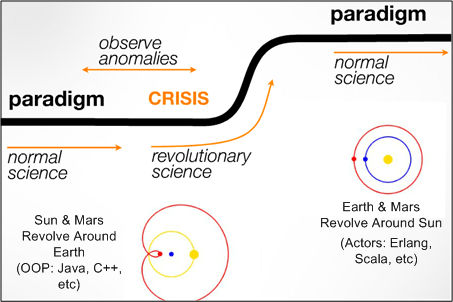

Best Actor Award

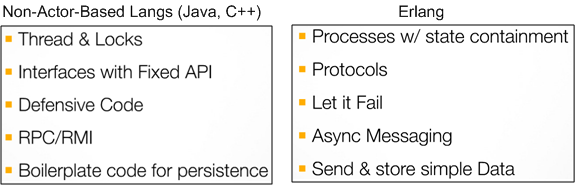

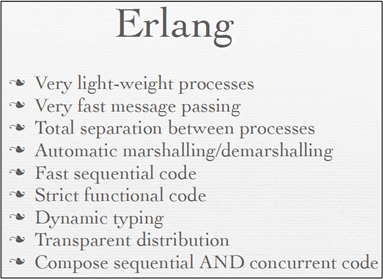

I recently watched (Trifork CTO and Erjang developer) Kresten Krab Thorup give this terrific talk: “Erlang, The Road Movie“. In his presentation, Kresten suggested that the 20+ year reign of the “objects” programming paradigm is sloooowly yielding to the next big problem-solving paradigm: autonomous “actors“. Using Thomas Kuhn‘s well known paradigm-change framework, he presented this slide (which was slightly augmented by BD00):

Kresten opined that the internet catapulted Java to the top of the server-side programming world in the 90s. However, the new problems posed by multi-core, cloud computing, and the increasing need for scalability and fault-tolerance will displace OOP/Java with actor-based languages like Erlang. Erlang has the upper-hand because it’s been evolved and battle-tested for over 20 years. It’s patiently waiting in the wings.

The slide below implies that the methods of OOP-based languages designed to handle post-2000 concurrency and scalability problems are rickety graft-ons; whereas the features and behaviors required to wrestle them into submission are seamlessly baked-in to Erlang’s core and/or its OTP library.

So, what do you think? Is Mr. Thorup’s vision for the future direction of programming correct? Is the paradigm shift underway? If not, what will displace the “object” mindset in the future. Surely, something will, no?

Too much of my Java programs are boilerplate code. – Kresten Krab Thorup

Too much of my C++ code is boilerplate code. – Bulldozer00

Java either steps up, or something else will. – Cameron Purdy

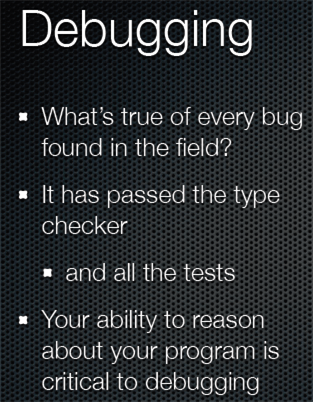

Reasonable Debugging

In Rich Hickey‘s QCon talk, “Simple Made Easy”, he hoisted this slide:

So, what can enhance one’s ability to “reason about” a program, especially a big, multi-threaded, multi-processing beast that maps onto a heterogeneous hodge-podge network of hardware and operating systems? Obviously, a stellar memory helps, but come on, how many human beings can remember enough detail in a >100K line code base to be able to debug field turds effectively and efficiently?

How about simplicity of design structure (whatever that means)? How about the deliberate and intentional use of a small set of nested, recurring patterns of interaction – both of the GoF kind and/or application specific ones? Or, shhhh, don’t say it too loudly, how about a set of layered blueprints that allow you and others to mentally “fly” over the software quickly at different levels of detail and from different aspect angles; without having to slodge through reams of “flat” code?

Do you, your managers, and/or your colleagues value and celebrate: simplicity of design structure; use of a small set of patterns of interaction; use of a set of blueprints? Do you and they walk the talk? If not, then why not? If so, then good for you, your org, your colleagues, your customers, and your shareholders.

No Lessons Learned

Because I’m fascinated by the causes and ubiquity of socio-technical project explosions, I try to follow technical press reports on the status of big government contracts. Here’s a recent article detailing the demise of the DoD’s Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS): “How to blow $6 billion on a tech project“.

Even though the reasons for big, software-intensive, multi-technology project failures have been well known for decades, disasters continue to be hatched and cancelled daily around the world by both public and private institutions everywhere – except yours, of course.

What follows are some snippets from the Ars Technica article and the JTRS wikipedia entry. The well-known, well-documented, contributory causes to the JTRS project’s demise are highlighted in bold type.

When JTRS and GMR launched, the services broke out huge wish lists when they drafted their initial requests for proposals on individual JTRS programs. While they narrowed some of these requirements as the programs were consolidated, requirements were constantly revised before, during, and after the design process.

In hindsight, the military badly underestimated the challenges before it.

First and foremost was the software development problem. When JTRS started, software-defined radio (SDR) was still in its infancy. The project’s SCA architecture allowed software to manipulate field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) in the radio hardware to reconfigure how its electronics functioned, exposing those FPGAs as CORBA objects. But when development began, hardware implementations of CORBA for FPGAs didn’t really exist in any standard form.

Moving code for a waveform from one set of radio hardware to another didn’t just mean a recompile—it often meant significant rewrites to make it compatible with whatever FGPAs were used in the target radio, then further tweaking to produce an acceptable level of performance. The result: the challenge of core development tasks for each of the initial designs was often grossly underestimated. Some of those issues have been addressed by specialized CORBA middleware, such as PrismTech’s OpenFusion, but the software tools have been long in coming.

When JTRS began, there was no WiFi, no 3G or no 4G wireless, and commercial radio communications was relatively expensive. But the consumer industry didn’t even look at SDR as a way to keep its products relevant in the future. Now, ASIC-based digital signal processors are cheap, and new products also tend to include faster chips and new hardware features; people prefer buying a new $100 WiFi router when some future 802.11z protocol appears instead of buying a $3,000 wireless router today that is “future proofed” (and you can’t really call anything based on CORBA “future proofed”).

“If JTRS had focused on rapid releases and taken a more modular approach, and tested and deployed early, the Army could have had at least 80 percent of what it wanted out of GMR today, instead of what it has now—a certified radio that it will never deploy.”

Having an undefined technical problem is bad enough, but it gets even worse when serious “scope creep” sets in during a 15-year project.

Each of the five sub-programs within JTRS aimed not at an incremental goal, but at delivering everything at once. That was a recipe for disaster.

By 2007 (10 years after start) the JTRS program as a whole had spent billions and billions—without any radios fielded.

In the fall of 2011, after 13 years of toil and $6B of our money wasted, the monster was put out of its misery. It was cancelled on October 2011 by the United States Undersecretary of Defense:

Our assessment is that it is unlikely that products resulting from the JTRS GMR development program will affordably meet Service requirements, and may not meet some requirements at all. Therefore termination is necessary.

And here’s what we, the taxpayers, have to show for the massive investment:

After 13 years in the pipeline, what those users saw was a radio that weighed as much as a drill sergeant, took too long to set up, failed frequently, and didn’t have enough range. (D’oh! and WTF!)

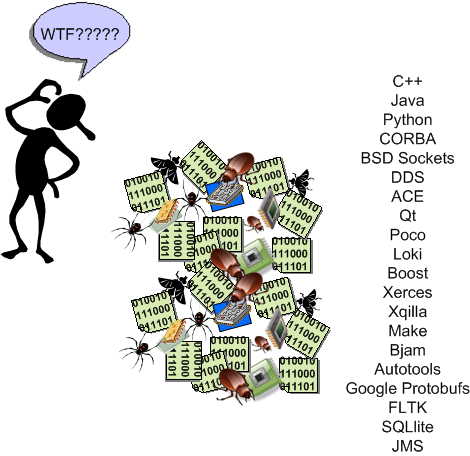

Misapplication Of Partially Mastered Ideas

Because the time investment required to become proficient with a new, complex, and powerful technology tool can be quite large, the decision to design C++ as a superset of C was not only a boon to the language’s uptake, but a boon to commercial companies too – most of whom developed their product software in C at the time of C++’s introduction. Bjarne Stroustrup‘s decision killed those two birds with one stone because C++ allowed a gradual transition from the well known C procedural style of programming to three new, up-and-coming mainstream styles at the time: object-oriented, generic, and abstract data types. As Mr. Stroustrup says in D&E:

Companies simply can’t afford to have significant numbers of programmers unproductive while they are learning a new language. Nor can they afford projects that fail because programmers over enthusiastically misapply partially mastered new ideas.

That last sentence in Bjarne’s quote doesn’t just apply to programming languages, but to big and powerful libraries of functionality available for a language too. It’s one challenge to understand and master a language’s technical details and idioms, but another to learn network programming APIs (CORBA, DDS, JMS, etc), XML APIs, SQL APIs, GUI APIs, concurrency APIs, security APIs, etc. Thus, the investment dilemma continues:

I can’t afford to continuously train my programming workforce, but if I don’t, they’ll unwittingly implement features as mini booby traps in half-learned technologies that will cause my maintenance costs to skyrocket.

BD00 maintains that most companies aren’t even aware of this ongoing dilemma – which gets worse as the complexity and diversity of their product portfolio rises. Because of this innocent, but real, ignorance:

- they don’t design and implement continuous training plans for targeted technologies,

- they don’t actively control which technologies get introduced “through the back door” and get baked into their products’ infrastructure; receiving in return a cacophony of duplicated ways of implementing the same feature in different code bases.

- their software maintenance costs keep rising and they have no idea why; or they attribute the rise to insignificant causes and “fix” the wrong problems.

I hate when that happens. Don’t you?

Highly Available Systems == Scalable Systems

In this QCon talk: “Building Highly Available Systems In Erlang“, Erlang programming language creator and highly-entertaining speaker Joe Armstrong asserts that if you build a highly available software system, then scalability comes along for “free” with that system. Say what? At first, I wanted to ask Joe what he was smoking, but after reflecting on his assertion and his supporting evidence, I think he’s right.

In his inimitable presentation, Joe postulates that there are 6 properties of Highly Available (HA) systems:

- Isolation (of modules from each other – a module crash can’t crash other modules).

- Concurrency (need at least two computers in the system so that when one crashes, you can fix it while the redundant one keeps on truckin’).

- Failure Detection (in order to fix a failure at its point of origin, you gotta be able to detect it first)

- Fault Identification (need post-failure info that allows you to zero-in on the cause and fix it quickly)

- Live Code Upgrade (for zero downtime, need to be able to hot-swap in code for either evolution or bug fixes)

- Stable Storage (multiple copies of data; distribution to avoid a single point of failure)

By design, all 6 HA rules are directly supported within the Erlang language. No, not in external libraries/frameworks/toolkits, but in the language itself:

- Isolation: Erlang processes are isolated from each other by the VM (Virtual Machine); one process cannot damage another and processes have no shared memory (look, no locks mom!).

- Concurrency: All spawned Erlang processes run in parallel – either virtually on one CPU, or really, on multiple cores and processor nodes.

- Failure Detection: Erlang processes can tell the VM that it wants to detect failures in those processes it spawns. When a parent process spawns a child process, in one line of code it can “link” to the child and be auto-notified by the VM of a crash.

- Fault Identification: In Erlang (out of band) error signals containing error descriptors are propagated to linked parent processes during runtime.

- Live Code Upgrade: Erlang application code can be modified in real-time as it runs (no, it’s not magic!)

- Stable Storage: Erlang contains a highly configurable, comically named database called “mnesia” .

The punch line is that systems composed of entities that are isolated (property 1) and concurrently runnable (property 2) are automatically scalable. Agree?