Archive

Dummkopf

I received this e-mail ad yesterday and felt a burning need (which will not be articulated) to post it on this bogus blog:

Shhhhhh! Don’t tell anyone, but I’m a fan of the “Dummies” series because…. I am a freakin’ Dummkopf. The first book I ever studied on C++ was “C++ For Dummies“. Double-Shhh!!!!

If you stumble across a “Software Engineering For Dummies” book, please notify me. Even better, keep a lookout for a “Software Engineering For Idiots” book.

Note: Since the links in jpg images don’t work, here’s the link you want to click, if you do indeed want to click it: Systems Engineering for Dummies – Effective Application Lifecycle Management Solutions Lab. Don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone. Mum’s the word.

Bounded Solution Spaces

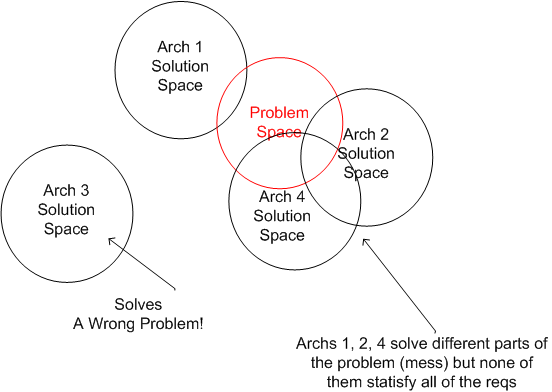

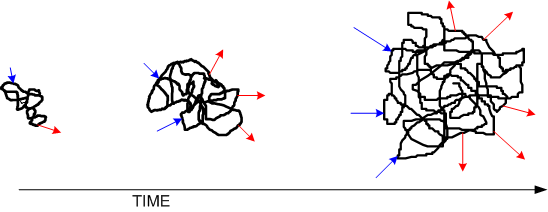

As a result of an interesting e-conversation with my friend Charlie Alfred, I concocted this bogus graphic:

Given a set of requirements, the problem space is a bounded (perhaps wrongly, incompletely, or ambiguously) starting point for a solution search. I think an architect’s job is to conjure up one or more solutions that ideally engulf the entire problem space. However, the world being as messy as it is, different candidates will solve different parts of the problem – each with its own benefits and detriments. Either way, each solution candidate bounds a solution space, no?

Methodology Taxonomy

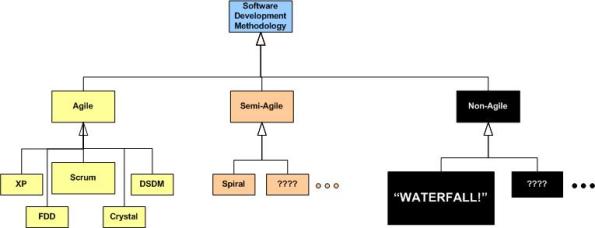

Here’s a feeble attempt at sharing a taxonomy of well-known (to BD00) software development methodologies:

Got any others to add to revision 1? How about variations on the hated “WATERFALL!” class? Where should the sprawling RUP go? What about “Scrum-but“? Does “kanban” fit into this taxonomy, or is it simply a practice to be integrated within a methodology? What about “Lean“?

Proprietary Extensions

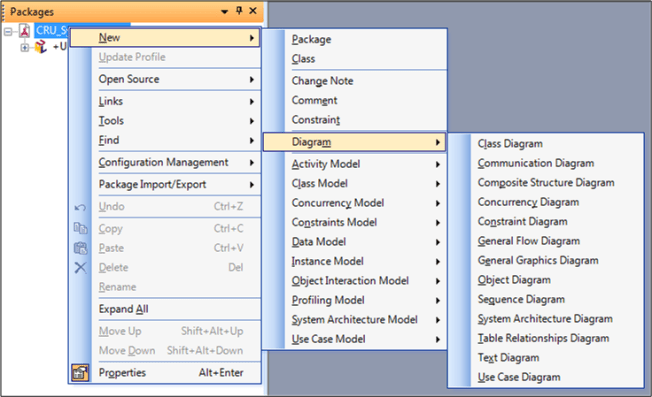

When using a tool or technology that implements a universal standard, beware of inadvertently using non-standard extensions that “lock” you into the vendor’s revenue stream.

The graphic below shows a screenshot from Artisan Real-time Studio version 7.2. Even though the tool implements the UML 2.0 standard, notice that there are several “non-UML” diagrams that you can create: “Constraint Diagram“, “General Flow Diagram“, etc. If you choose to create and use these proprietary extensions, then you’re sh*t out of luck if you get pissed off at Atego and want to port your model over to a different UML tool vendor with a better and/or less expensive solution. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

I’m not trying to single out Atego here. Every commercial vendor, especially of expensive tools, bakes-in a few proprietary extensions to give them an edge over the competition. The sneakier ones don’t annotate or make obvious which features are proprietary – so beware.

A Risky Affair

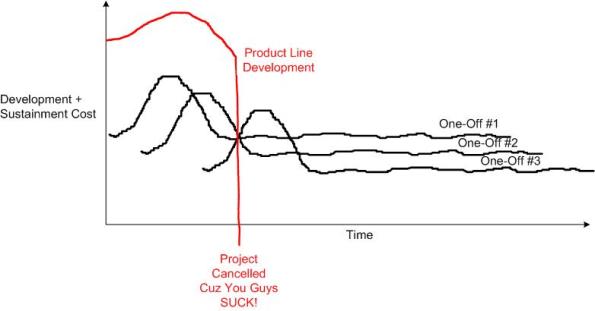

The figure below shows the long term savings potential of a successful Software Product Line (SPL) over a one-off system development strategy. Since 2/3 to 3/4 of the total lifecycle cost of a long-lived software system is incurred during sustainment (and no, I don’t have any references handy), with an SPL infrastructure in place, patience and discipline (if you have them) literally pay off. Even though short term costs and initial delivery times suffer, cost and time savings start to accrue “sometime” downstream. Of course, if your business only produces small, short-lived products, then implementing an SPL approach is not a very smart strategy.

If you think developing a one-off, software-intensive product is a risky affair, then developing an SPL can seem outright suicidal. If your past history indicates that you suck at one-off development (you do track and reflect upon past schedule/cost/quality metrics as your CMMI-compliant process sez you do, right?), then rejecting all SPL proposals is the only sane thing to do…. because this may happen:

The time is gone, the money is gone, and you’ve got nothing to show for it. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Related Articles

The Odds May Not Be Ever In Your Favor (Bulldozer.com)

Out Of One, Many (Bulldozer.com)

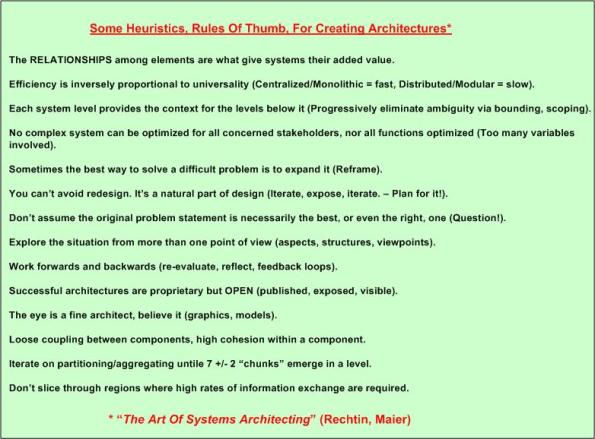

Rules Of Thumb

Look what I dug up in my archives:

Hopefully, this list may provide some aid to at least one poor, struggling soul out in the ether.

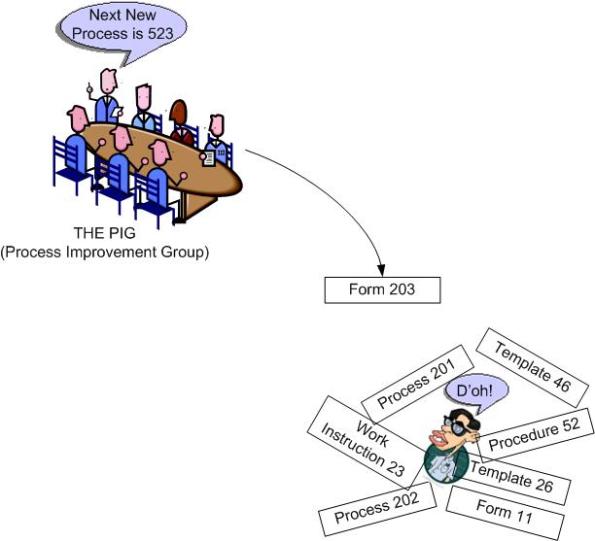

Prune Me, Please

In “Integrating CMMI and Agile Development“, Paul E. McMahon asserts that even though they’d like to, many orgs don’t “prune” their fatty, inefficient, and costly processes because:

..it requires a commitment of the time of key people in the organization who really use the processes. Usually these people are just too busy with direct contract work and the priority doesn’t allow this to happen.

One of BD00’s heroes, the Oracle of Omaha, has a different take on it:

There seems to be some perverse human characteristic that likes to make easy things difficult. – Warren Buffet

Of course, both reasons could apply.

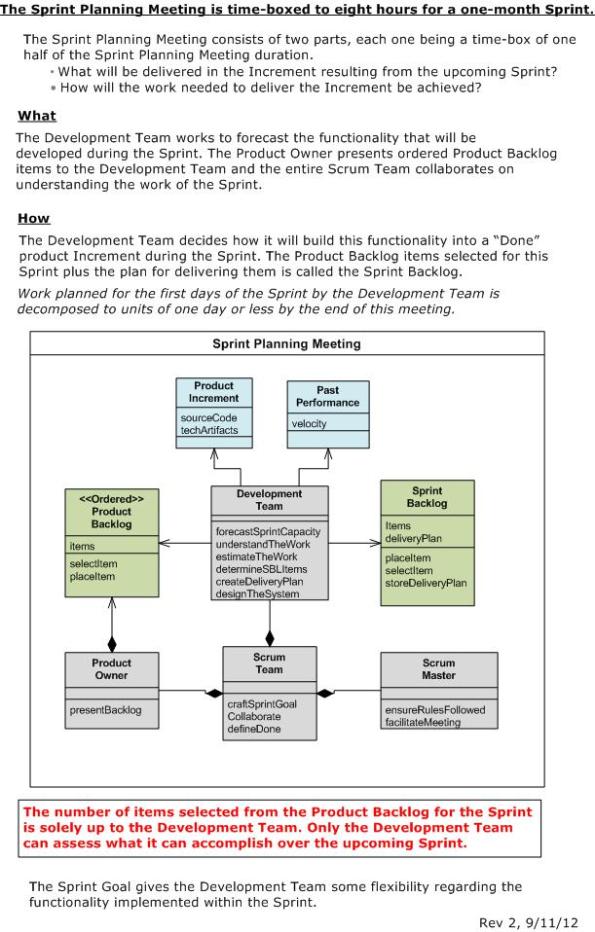

The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting

Since the UML Scrum Cheat Sheet post is getting quite a few page views, I decided to conjure up a class diagram that shows the static structure of the Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (SPM).

The figure below shows some text from the official Scrum Guide. It’s followed by a “bent” UML class diagram that transforms the text into a glorious visual model of the SPM players and their responsibilities.

In unsuccessful Scrum adoptions where a hierarchical command & control mindset is firmly entrenched, I’ll bet that the meeting is a CF (Cluster-f*ck) where nobody fulfills their responsibilities and the alpha dudes dominate the “collaborative” decision making process. Maybe that’s why Ramblin’ Scott Ambler recently tweeted:

Everybody is doing agile these days. Even those that aren’t. – Scott Ambler

D’oh! and WTF! – BD00

Of course, BD00 has no clue what shenanigans take place during unsuccessful agile adoptions. In the interest of keeping those consulting and certification fees rolling in, nobody talks much about those. As Chris Argyris likes to say, they’re “undiscussable“. So, Shhhhhhh!

Bring Back The Old

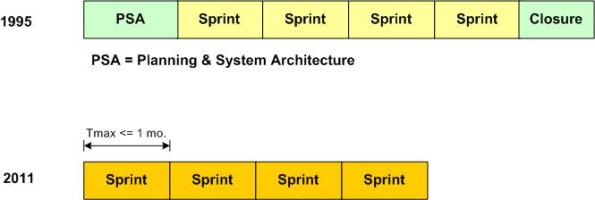

The figure below shows the phases of Scrum as defined in 1995 (“Scrum Development Process“) and 2011 (The 2011 Scrum Guide). By truncating the waterfall-like endpoints, especially the PSA segment, the development framework became less prescriptive with regard to the front and back ends of a new product development effort. Taken literally, there are no front or back ends in Scrum.

The well known Scrum Sprint-Sprint-Sprint-Sprint… work sequence is terrific for maintenance projects where the software architecture and development/build/test infrastructure is already established and “in-place“. However, for brand new developments where costly-to-change upfront architecture and infrastructure decisions must be made before starting to Sprint toward “done” product increments, Scrum no longer provides guidance. Scrum is mum!

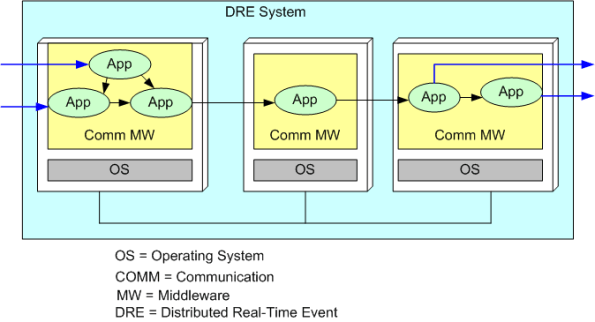

The figure below shows a generic DRE system where raw “samples” continuously stream in from the left and value-added info streams out from the right. In order to minimize the downstream disaster of “we built the system but we discovered that the freakin’ architecture fails the latency and/or thruput tests!“, a bunch of critical “non-functional” decisions and must be made and prototyped/tested before developing and integrating App tier components into a potentially releasable product increment.

I think that the PSA segment in the original definition of Scrum may have been intended to mitigate the downstream “we’re vucked” surprise. Maybe it’s just me, but I think it’s too bad that it was jettisoned from the framework.

The time’s gone, the money’s gone, and the damn thing don’t work!

From Complexity To Simplicity

As the graphic below shows, when a system evolves, it tends to accrue more complexity – especially man-made systems. Thus, I was surprised to discover that the Scrum product development framework seems to have evolved in the opposite direction over time – from complexity toward simplicity.

The 1995 Ken Schwaber “Scrum Development Process“ paper describes Scrum as:

The 1995 Ken Schwaber “Scrum Development Process“ paper describes Scrum as:

Scrum is a management, enhancement, and maintenance methodology for an existing system or production prototype.

However, The 2011 Scrum Guide introduces Scrum as:

Scrum is a framework for developing and sustaining complex products.

Thus, according to its founding fathers, Scrum has transformed from a “methodology” into a “framework“.

Even though most people would probably agree that the term “framework” connotes more generality than the term “methodology“, it’s arguable whether a framework is simpler than a methodology. Nevertheless, as the figure below shows, I think that this is indeed the case for Scrum.

In 1995, Scrum was defined as having two bookend, waterfall-like, events: PSA and Closure. As you can see, the 2011 definition does not include these bookends. For good or bad, Scrum has become simpler by shedding its junk in the trunk, no?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that is not there; because it isn’t needed. (Middle management?)

I think, but am not sure, that the PSA event was truncated from the Scrum definition in order to discourage inefficient BDUF (Big Design Up Front) from dominating a project. I also think, but am not sure, that the Closure event was jettisoned from Scrum to dispel the myth that there is a “100% done” time-point for the class of product developments Scrum targets. What do you think?

Related articles

- Scrum Cheat Sheet (bulldozer00.com)

- Ultimately And Unsurprisingly (bulldozer00.com)

- Introduction to scrum (slideshare.net)

- Scrum Master, a management position? (scrumguru.wordpress.com)

- Developing, and succeeding, with Scrum (techworld.com.au)