Archive

Proximity In Space And Time

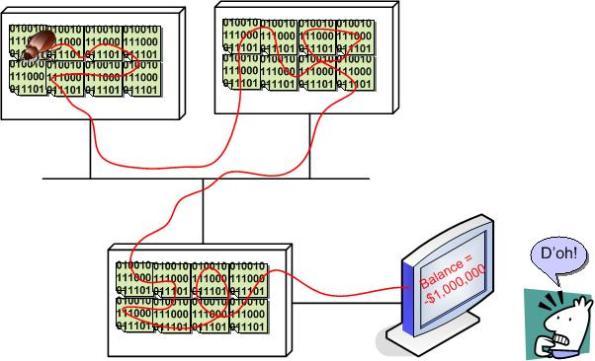

When a failure occurs in a complex, networked, socio-technical system, the probability is high that the root cause is located far away from the failure detection point in time, space, or both. The progression in time goes something like this:

fault ———–> error———-> error—————–>error——>failure discovered!

An unanticipated fault begets an error, which begets another error(s), which begets another error(s), etc, until the failure is manifest via loss of life or money somewhere and sometime downstream in the system. In the case of a software system, the time from fault to catastrophic failure may take milliseconds, but the distance between fault and failure can be in the 100s of thousands of lines of source code sprinkled across multiple machines and networks.

Let’s face it. Envisioning, designing, coding, and testing for end-to-end “system level” error conditions in software systems is unglamorous and tedious (unless you’re using Erlang – which is thoughtfully designed to lessen the pain). It’s usually one of the first things to get jettisoned when the pressure is ratcheted up to meet some arbitrary schedule premised on a baseless, one-time, estimate elicited under duress when the project was kicked-off. Bummer.

Heaven And Hell

This is one of those picture-only posts where BD00 invites you to fill in the words of the missing story…

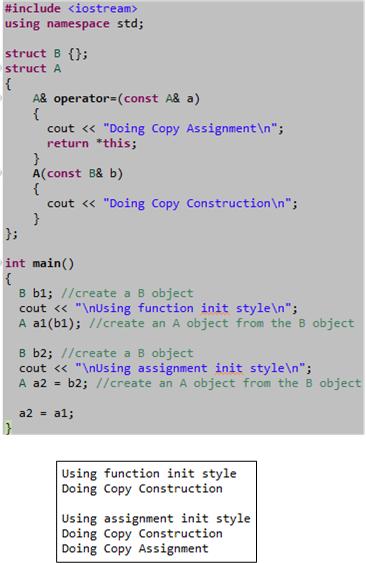

Cpp Initialization Styles

For most cases, the “assignment” and “function” styles of initializing objects in C++ are the same. However, as the example below shows, in some edge cases, the function style of initialization can be more efficient. Nevertheless, for all practical purposes they are essentially the same since the compiler may optimize away the actual assignment step in the 2 step “assignment” style.

The motivation for this post came from a somewhat lengthy debate with a fellow member of the “C++ Developers Group” on LinkedIn.com. I knew that a subtle difference between the two initialization styles existed, but I couldn’t remember where I read about it. However, after I wrote this post, I browsed through my C++ references again and I found the source. The difference is explained in a much more intelligible and elegant way in “Efficient C++ Performance Programming Techniques“. Specifically, the discussion and example code in Chapter 5, “Temporaries – Object Definition“, does the trick.

Update 12/3/12

As my colleague friend pointed out, the above post is outright wrong with respect to the possibility of the assignment operator being used during initialization. Assignment is only used to copy values from one existing object into another existing object – not when an object is being created. That’s what constructors do. The “Doing Copy Assignment” text in the above code only prints to the console because of the last a2 = a1 statement in main(), which I put there to stop the g++ compiler from complaining about an unused variable. D’oh!

The example in the “Efficient” book that triggered our discussion is provided here:

The authors go on to state:

Only the first form of initialization is guaranteed, across compiler implementations, not to generate a temporary object. If you use forms 2 or 3, you may end up with a temporary, depending on the compiler implementation. In practice, however, most compilers should optimize the temporary away, and the three initialization forms presented here would be equivalent in their efficiency.

Ever since I read that book many years ago, I’ve always preferred to use the “function” style initialization over the “assignment” style. But it’s just a personal preference.

Code First And Discover Later

In my travels through the whacky world of software development, I’ve found that bottom up design (a.k.a code first and “discover” the real design later) can lead to lots of unessential complexity getting baked into the code. Once this unessential complexity, in the form of extraneous classes and a rats nest of unneeded dependencies, gets baked into the system and the contraption “appears to work” in a narrow range of scenarios, the baker(s) will tend to irrationally defend the “emergent” design to the death. After all, the alternative would be to suffer humility and perform lots of risky, embarrassing, and ego-busting disentanglement rework. Of course, all of these behaviors and processes are socially unacceptable inside of orgs with macho cultures; where publicly admitting you’re wrong is a career-ending move. And that, my dear, is how we have created all those lovable, “legacy” systems that run the world today.

Don’t get BD00 wrong here. The esteemed one thinks that bottom up design and coding is fine for small scoped systems with around 7 +/- 2 classes (Miller’s number), but this “easy and fun and fast” approach sure doesn’t scale well. Even more ominously, the bottom up coding and emergent design strategy is unacceptable for long-lived, safety-critical systems that will be scrutinized “later on” by external technical inspectors.

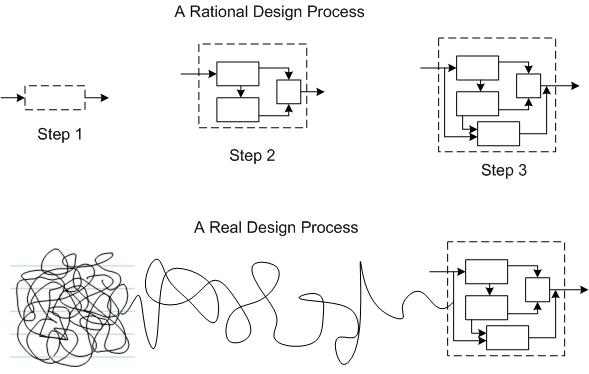

Faking Rationality

I recently dug up and re-read the classic Parnas/Clement 1986 paper: “A Rational Design Process: How And Why To Fake It“. Despite the tendency of people to want to desperately believe the process of design is “rational“, it never is. The authors know there is no such thing as a sequential, rational design process where:

- There’s always a good reason behind each successive design decision.

- Each step taken can be shown to be the best way to get to a well defined goal.

The culprit that will always doom a rational design process is “learning“:

Many of the details only become known to us as we progress in the implementation (of a design). Some of the things that we learn invalidate our design and we must backtrack (multiple times during the process). The resulting design may be one that would not result from a rational design process. – Parnas/Clements

Since “learning“, in the form of going backwards to repair discovered mistakes, is a punishable offense in social command & control hierarchies where everyone is expected to know everything and constantly march forward, the best strategy is to cover up mistakes and fake a rational design process when the time comes to formally present a “finished” design to other stakeholders.

Even though it’s unobtainable, for some strange reason, Spock-like rationality is revered by most orgs. Thus, everyone in org-land plays the “fake-it” game, whether they know it or not. To expect the world to run on rationality is irrational.

Executives preach “evidence-based decision-making“, but in reality they practice “decision-based evidence-making“.

The Wagile Hortoise

I’m loathe to put any words to the following dorky picture lest I’m forced to “rationally” defend it to the death and justify its reason for being . It’s meant for your viewing pleasure (displeasure?) only. 🙂

Four Possible Paths, Eight Possible Outcomes

The graphic below transforms the title of this post into a visual manifestation that can be discussed “rationally” (<— LOL!).

The graphic shows that pursuing any of the four path selections can lead to a “number 2” outcome. It’s just a matter of how much time and money are exhausted before the steaming pile is discovered. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Obviously, the path to the holy grail is D->1. Simply take whatever info is known about the problem, code up the solution, get paid tons o’ munny, move on to the next problem to be solved, and never look back. Whoo Hoo! I love when that happens.

A Real Renaissance

For quite some time now, I’ve been hearing that C++ has been undergoing a resurgence of interest; a renaissance. However, until recently, I couldn’t tell if the claim was real, or just some hype coming out of the C++ community to fruitlessly combat the rise of a plethora of new languages.

Well, I’m convinced that the renaissance is legit. The slides below, pilfered from Herb Sutter‘s “The Future Of C++” talk at Microsoft Build 2012, introduced the formation of a new C++ trade group, the “Standard C++ Foundation“.

Note that there are some big guns with deep pockets backing the foundation along with a cadre of brilliant and dedicated directors at the helm.

It’s a good time to be a C++ programmer, so join the renaissance and start learning the new features and libraries offered up in C++11. Of course, if your technical management is not forward looking and it’s tight with training dollars, you’ll have to do it on your own time, covertly, behind the scenes. But it will not only be fun, it will enhance your marketability.

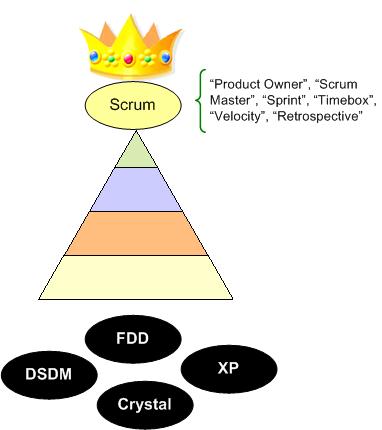

King Of The Hill

Scrum is an agile approach to software development, but it’s not the only agile approach. However, because of its runaway success of adoption compared to other agile approaches (e.g. XP, DSDM, Crystal, FDD), a lot of the pro and con material I read online seems to assume that Agile IS Scrum.

This nitpicking aside, until recently, I wondered why Scrum catapulted to the top of the agile heap over the other worthy agile candidates. Somewhere online, someone answered the question with something like:

“Scrum is king of the hill right now because it’s closer to being a management process than a geeky, code-centric set of practices. Thus, since enlightened executives can pseudo-understand it, they’re more likely to approve of its use over traditional prescriptive processes that only provide an illusion of control and a false sense of security.”

I think that whoever said that is correct. Why do you think Scrum is currently the king of the hill?

Related articles

- The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (bulldozer00.com)

- Scrum And Non-Scrum Interfaces (bulldozer00.com)

The C++ Product Roadmap

Fresh from the ISO C++ chairman himself, Herb Sutter, I present you with the C++ product roadmap:

If all goes according to plan, a minor release of the ISO standard will be hatched in 2014. By minor, Herb means that it will be mostly bug fixes to C++11, plus a filesystem library based on Boost.org‘s brilliant work. The networking library, which is big and being developed by a large group of smart people, will be hatched incrementally in a series of Technical Specifications (TS).

The main point that Herb stressed when he hoisted the slide was that “the past is not a good predictor of the future“. If all goes according to plan, the time between major releases of the standard will have been cut from 13 years to 6.