Archive

Admittance Of Imperfection

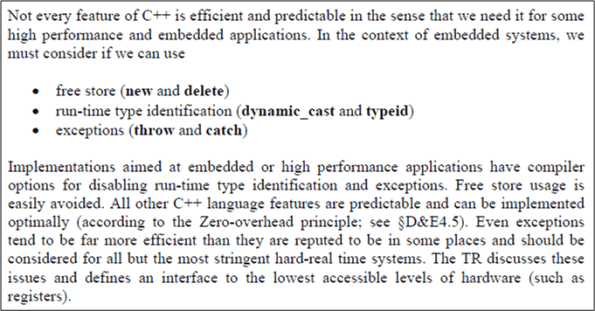

One of the traits I admire most about Bjarne Stroustrup is that he’s not afraid to look “imperfect” and point out C++’s weaknesses in certain application contexts. In his “Technical Report On C++ Performance“, Mr. Stroustrup helpfully cautions real time programmers to think about the risks of using the unpredictable/undeterministic features of the language:

Of course, C++ antagonists are quick to jump right on his back when Bjarne does admit to C++’s imperfections in specific contexts: “see, I told you C++ sux!“.

Here’s a challenge for programmers who read this inane blog. Can you please direct me to similar “warning” clauses written by other language designers? I’m sure there are many out there. I just haven’t stumbled across one yet.

Codan The Barbarian

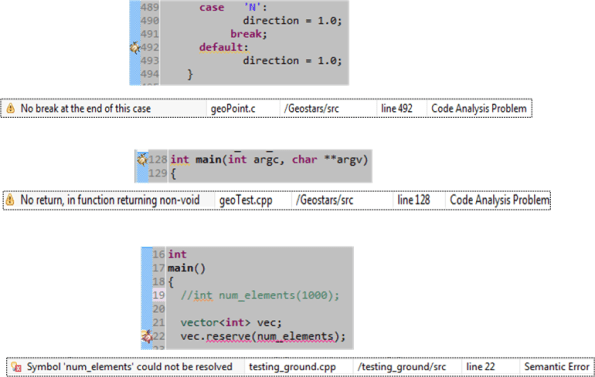

In the Indigo release of Eclipse‘s C++ Development Tools (CDT) plugin, the Codan static code analyzer runs in real time as you type in your code. As shown below, you can customize the rule set that Codan enforces via the “Preferences/C++/Code Analysis” dialog window. (My fave is the “ambiguous problem” entry.)

The figure below shows a few examples of Codan in action. While typing in code, a gold (warning) or red (error) bug icon appears adjacent to the line number of the crappy code you write.

Some of Codan’s warnings and errors are also detected by good compilers, but it’s kind of neat that you can discover and correct your defects before running the compiler/linker. This feature is a boon for large programs that take a while to compile and link.

As a long time developer, I’m thrilled to death to have open source tools like Eclipse available to dolts like BD00. I remember the old days when there were not many commercial tools available, yet alone high caliber, open source tool suites like Eclipse.

Different Goals And Unfair Comparisons

At the behest of a work colleague, I revisited the Java programming language. I re-read James Gosling‘s 1995 white paper that introduced the language and I perused several Java-related wikipedia articles. Using those sources and Bjarne Stroustrup‘s “Evolving a language in and for the real world: C++ 1991-2006” paper, I developed the following side by side “design goals” lists:

In spite of these radically different design goals, people (including myself) continue to insist on comparing the languages in passionately irrational ways. If both language designs were driven by a common set of goals, then objectively valid comparisons could be made.

Java was intentionally designed from a blank sheet; unfettered from the ground up. Au contraire, C++ was intentionally designed by extending C and attempting to fix it’s short comings without breaking millions of lines of deployed code. It’s like comparing apples to oranges, dontcha think?

Doing Double Duty

In the industry I work in, domain analysts are called system engineers. The best system engineers, who mostly have electrical engineering backgrounds, know how to read code. Specifically, they know how to read C code because they learned it as a secondary subject in conjunction with hard core engineering courses (I actually learned FORTRAN in engineering school – because C hadn’t taken over the world yet).

Since the best engineers continuously move forward and grow, they often take on the challenge of moving from C to C++. One of the features that tends to trip them up is the dual use of the “&” token in C++ for “address of” and “reference to“. In C, there are no “references”, and hence, the “&” serves 1 purpose: it serves as the “address of” operator when applied to an identifier.

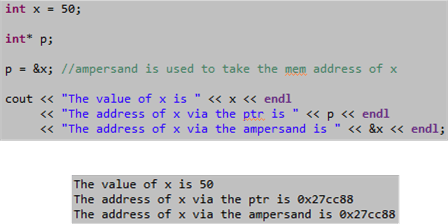

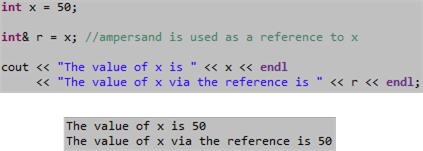

The code snippet and its associated output below show the classic, single purpose use of the “&” operator in C to obtain the “address of” an integer type identified by “x”.

In C++, the “&” token serves two purposes. The first one is the same as in C; when applied to an identifier, it returns the “address of” the object represented by the identifier. As the code below illustrates, the second C++ use is when it is applied to a type; it represents a “reference to” (a.k.a “alias to”) an object.

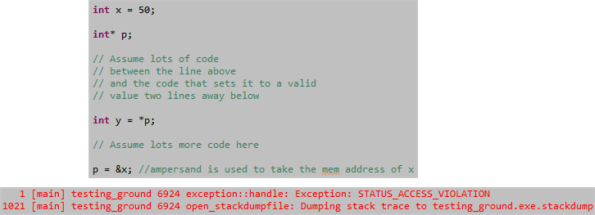

So, what good is a reference when C++ already has pointers? References are safer than pointers. When defining a pointer, C++ (like C) doesn’t require that it be initialized (as the first code fragment shows) to a valid address value immediately. Thus, if the code that initializes the pointer’s value to a valid address is far away from it’s definition, there’s a danger of mistakingly using it before the valid address has been assigned to it – as shown below. D’oh!

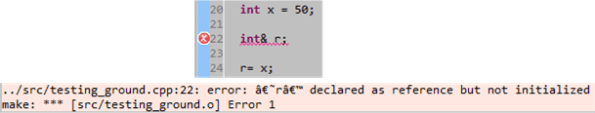

Since C++ requires a reference type to be initialized at its point of definition, there’s no chance of it ever being used in an invalid state. C++ compilers won’t allow it:

Another reason for “preferring” references over pointers in C++ is the notational convenience it provides for accessing class members:

It may be arguable, but besides saving one keystroke, using the “.” method of access instead of the “->” symbol provides for cleaner code, no?

So there you have it. If you’re a system engineer that is struggling to learn C++ for self-growth or code reviews, or a programmer trying to move from C onward toward C++ proficiency, hopefully this blog post helps. I know that expert C++ book authors can do a better job of the “what, how, and why” of references, but I wanted to take a shot at it myself. How did I do?

Note: I used Eclipse/cygwin/gcc over Win Vista for the code in this post. Do you see those annoying turd characters that surround the “r” in the pink compiler error output above? I’ve been trying to find out how to get rid of those pesky critters for weeks. As you can see, I’ve been unsuccessful. Can you help me out here?

Biased Comparison

Let me preface this post by saying what lots of level-headed people (rightly) say: “choose the right tool for the right job“. Ok, having said that, take a quick glance again at the first word in this post’s title, and then let’s move on….

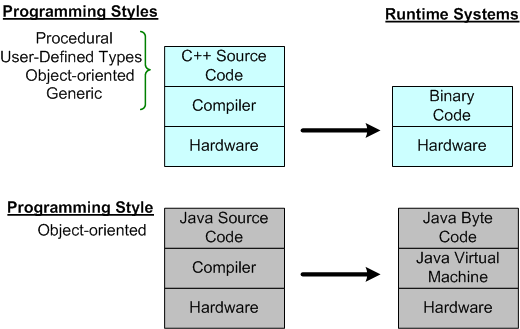

Take a look at the diagram below in terms of flexibility and performance. C++ provides developers with several programming style choices to solve the problem at hand and Java (Smalltalk, Eiffel) “handcuffs” programmers with no choice (in BD00’s twisted mind, Java Generics are clumsy and they destroy the OO purity of Java, and thus, don’t count).

Regarding program performance (<- ya gotta check this interactive site out), there’s “virtually” no way that a Java program running on top of an overhead “middleman” virtual machine can be faster than native code running on the same CPU hardware. Of course, there can be the rare exception where a crappy C++ compiler is pitted against a highly optimized (and over-hyped), “JIT” Java compiler .

Nevertheless, a price has to be paid for increased power and flexibility. And that price is complexity. The “learnability” of C++ is way more time consuming than Java. In addition, although it’s easy to create abominations in any language, it’s far easier to “blow your leg off” using C++ than using Java (or just about any other language except assembler).

Having spewed all this chit, I’d like to return to the quote in this post’s first paragraph: “choose the right tool for the right job“. Seriously consider using C++ for jobs like device drivers, embedded real-time systems, operating systems, virtual machines, and other code that needs to use hardware directly. Use Java, or even simpler languages, for web sites and enterprise IT systems.

The main weakness of OOP is that too many people try to force too many problems into a hierarchical mould. Not every program should be object-oriented. As alternatives, consider plain classes, generic programming, and free-standing functions (as in math, C, and Fortran). – Bjarne Stroustrup

Constrained Evolution

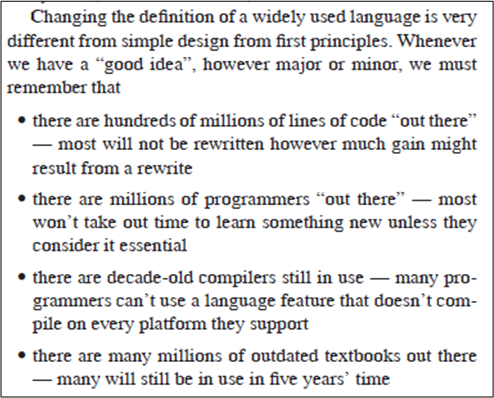

In general, I’m not a fan of committee “output“. However, I do appreciate the work of the C++ ISO committee. In “Evolving a language in and for the real world”, Bjarne Stroustrup articulates the constraints under which the C++ committee operates:

Bjarne goes on to describe how, if the committee operated with reckless disregard for the past, C++ would fade into obscurity (some would argue that it already has):

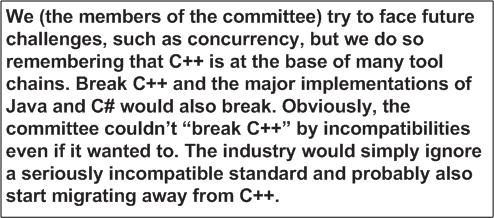

Personally, I like the fact that the evolution of C++ (slow as it is) is guided by a group of volunteers in a non-profit organization. Unlike for-profit Oracle, which controls Java through the veil of the “Java Community Process“, and for-profit Microsoft, which controls the .Net family of languages, I can be sure that the ISO C++ committee is working in the interest of the C++ user base. Language governance for the people, by the people. What a concept.

Vector Performance

std::vector, or built-in array, THAT is the question – Unshakenspeare

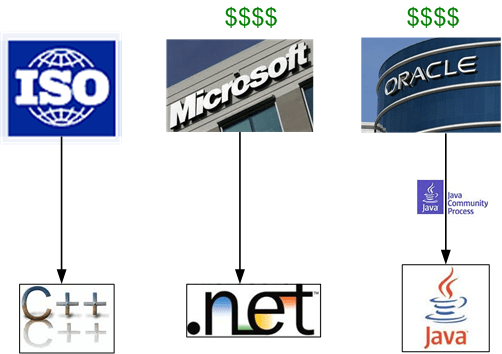

In C++, all post-beginner programmers know about the performance vs. maintainability tradeoff regarding std::vector and built-in arrays. Because they’re less abstract and closer to the “metal“, read/write operations on arrays are faster. However, unlike a std::vector container, which stores its size cohesively with its contents, every time an array is passed around via function calls, the size of the array must also be explicitly passed with the “pointer” – lest the callees loop themselves into never never land cuz they don’t know how many elements reside within the array (I hate when that happens!).

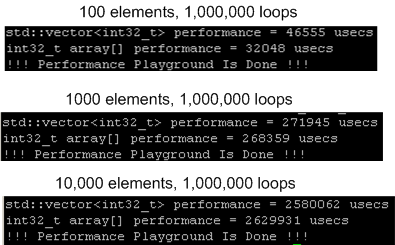

To decide which type to use in the critical execution path on the project that I’m currently working on, I whipped up a little test program (available here) to measure the vector/array performance difference on the gcc/linux/intel platform that we’re developing on. Here are the results – which consistently show a 60% degradation in performance when a std:vector is used instead of a built-in array. I thought it would be lower. Bummer.

But wait! I ain’t done yet. After discovering that I was compiling with the optimizer turned off (-O0), I rebuilt and re-ran with -O3. Here are the results:

Unlike the -O0 test runs, in which the measured performance difference was virtually independent of the number of elements stored within the container, the performance degradation of std::vector decreases as the container size increases. Hell, for the 10K element, 1M loop run, the performance of std::vector was actually 2% higher than the plain ole array. I’ve deduced that std::vector::operator[] is inlined, but when the optimizer is turned “off“, the inlining isn’t performed and the function call overhead is incurred for each elemental access.

If you’re so inclined, please try this experiment at home and report your results back here.

Something’s Uh Foot?

It’s my understanding that the financial crisis was precipitated by the concoction of exotic investment instruments like derivatives and derivatives of derivatives that not even quantum physicists could understand.

Well, it looks like the shenanigans may not be over. Take a look at this sampling of astronomically high paying jobs from LinkedIn.com for C++ programmers:

Did the financial industry learn a lesson from the global debacle, or was it back to business as usual when the dust settled? Hell, I don’t know. That’s why I’m askin’ you.

The Parallel Patterns Library

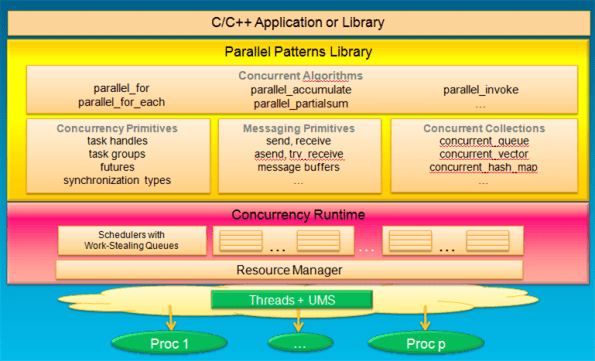

Kate Gregory doesn’t work for Microsoft, but she’s a certified MVP for C++. In her talk at Tech Ed North America, “Modern Native C++ Development for Maximum Productivity”, she introduced the Parallel Patterns Library (PPL) and the concurrency runtime provided in Microsoft Visual C++ 2010.

The graphic below shows how a C++ developer interfaces with the concurrency runtime via the facilities provided in the PPL. Casting aside the fact that the stack only runs on Windows platforms, it’s the best of both worlds – parallelism and concurrency.

Note that although they are provided via the “synchronization types” facilities in the PPL, writing multi-threaded programs doesn’t require programmers to use error-prone locks. The messaging primitives (for inter-process communication) and concurrent collections (for intra-process communication) provide easy-to-use abstractions over sockets and locks programming. The messy, high-maintenance details are buried out of programmer sight inside the concurrency runtime.

I don’t develop for Microsoft platforms, but if I did, it would be cool to use the PPL. It would be nice if the PPL + runtime stack was platform independent. But the way Microsoft does business, I don’t think we’ll ever see linux or RTOS versions of the stack. Bummer.

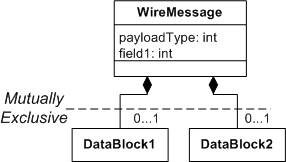

State Of The Union

For the multi-threaded CSCI that I’m developing, I’ve got to receive and decode serialized messages off of “the wire” that conform to the design below. Depending on the value of “payloadType” in the message, each instance of the “WireMessage” class will have either an instance of “DataBlock1” or “DataBlock2” embedded within it.

After contemplating how to implement the deserialized replica of the message within my code, I decided to use a union to keep the message at a fixed size as it is manipulated and propagated forward through the non-polymorphic queues that connect the threads together in the CSCI.

The figure below shows side by side code snippets of the use of a union within a class. The code on the left compiled fine, but the compiler barfed on the code on the right with a “data member with constructor not allowed in union” error. WTF?

At first, I didn’t understand why the compiler didn’t like the code on the right. But after doing a little research, it made sense.

Unlike the code on the left, which has empty compiler-generated ctor, dtor, and copy operations, the DataBlock1 class on the right has a user-declared ctor – which trips up the compiler even though it is empty. When an object of FixedMessage type is created or destroyed, the compiler wouldn’t know which union member constructor or destructor to execute for the two class members in the union (built-in types like “int” don’t have ctors/dtors). D’oh!

Note: After I wrote this post, I found this better explanation on Bjarne Stroustrup’s C++0x FAQ page:

But of course, the restrictions on which user-defined types may be included in a union will be relaxed a bit in C++11. The details are in the link provided above.