Archive

The Bogus SE/SE Rule

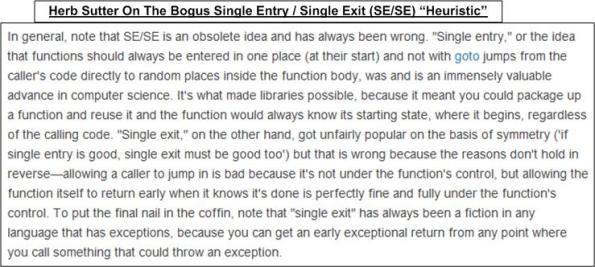

Relatively recently, I participated in a debate with a peer regarding the sacredness of the Single Entry / Single Exit (SE/SE) “rule” of programming. I wish I had this eloquent Herb Sutter treatise on hand when it occurred:

Woot! Now that I’ve stashed the case against SE/SE nazi “enforcement” on this blawg, I’m armed and ready to confront the next brainwashed purist on the matter.

Freakin’ Oops!

With great power there must also come… great responsibility – Stan Lee

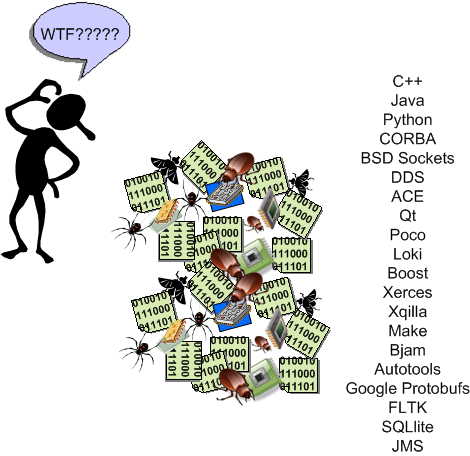

C++, being as sprawling and powerful and flexible as it is, rightly gets dinged for its propensity to bite you in the ass (if you don’t fully understand a language feature you’re trying to use). Thus, many C++ programming book authors point out common “gotchas” while teaching the language to their readers.

The graphic below depicts some “watchout!” snippets from four different, popular C++ programming books. As you might surmise from the picture, my favorite word in a C++ programming book is (freakin’) “Oops!”.

Rule-Based Safety

In this interesting 2006 slide deck, “C++ in safety-critical applications: the JSF++ coding standard“, Bjarne Stroustrup and Kevin Carroll provide the rationale for selecting C++ as the programming language for the JSF (Joint Strike Fighter) jet project:

First, on the language selection:

- “Did not want to translate OO design into language that does not support OO capabilities“.

- “Prospective engineers expressed very little interest in Ada. Ada tool chains were in decline.“

- “C++ satisfied language selection criteria as well as staffing concerns.“

They also articulated the design philosophy behind the set of rules as:

- “Provide “safer” alternatives to known “unsafe” facilities.”

- “Craft rule-set to specifically address undefined behavior.”

- “Ban features with behaviors that are not 100% predictable (from a performance perspective).”

Note that because of the last bullet, post-initialization dynamic memory allocation (using new/delete) and exception handling (using throw/try/catch) were verboten.

Interestingly, Bjarne and Kevin also flipped the coin and exposed the weaknesses of language subsetting:

What they didn’t discuss in the slide deck was whether the strengths of imposing a large coding standard on a development team outweigh the nasty weaknesses above. I suspect it was because the decision to impose a coding standard was already a done deal.

Much as we don’t want to admit it, it all comes down to economics. How much is the lowering of the risk of loss of life worth? No rule set can ever guarantee 100% safety. Like trying to move from 8 nines of availability to 9 nines, the financial and schedule costs in trying to achieve a Utopian “certainty” of safety start exploding exponentially. To add insult to injury, there is always tremendous business pressure to deliver ASAP and, thus, unconsciously cut corners like jettisoning corner-case system-level testing and fixing hundreds of “annoying” rules violations.

Does anyone have any data on whether imposing a strict coding standard actually increases the safety of a system? Better yet, is there any data that indicates imposing a standard actually decreases the safety of a system? I doubt that either of these questions can be answered with any unbiased data. We’ll just continue on auto-believing that the answer to the first question is yes because it’s supposed to be self-evident.

Cpp Initialization Styles

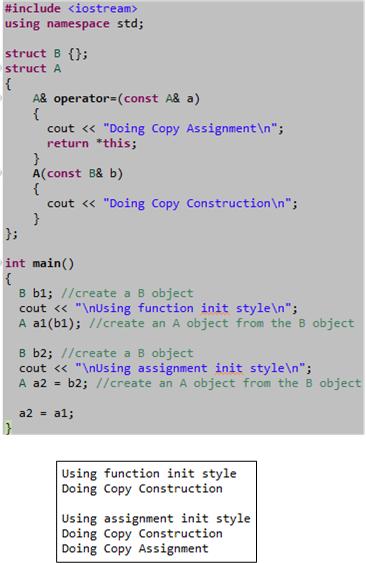

For most cases, the “assignment” and “function” styles of initializing objects in C++ are the same. However, as the example below shows, in some edge cases, the function style of initialization can be more efficient. Nevertheless, for all practical purposes they are essentially the same since the compiler may optimize away the actual assignment step in the 2 step “assignment” style.

The motivation for this post came from a somewhat lengthy debate with a fellow member of the “C++ Developers Group” on LinkedIn.com. I knew that a subtle difference between the two initialization styles existed, but I couldn’t remember where I read about it. However, after I wrote this post, I browsed through my C++ references again and I found the source. The difference is explained in a much more intelligible and elegant way in “Efficient C++ Performance Programming Techniques“. Specifically, the discussion and example code in Chapter 5, “Temporaries – Object Definition“, does the trick.

Update 12/3/12

As my colleague friend pointed out, the above post is outright wrong with respect to the possibility of the assignment operator being used during initialization. Assignment is only used to copy values from one existing object into another existing object – not when an object is being created. That’s what constructors do. The “Doing Copy Assignment” text in the above code only prints to the console because of the last a2 = a1 statement in main(), which I put there to stop the g++ compiler from complaining about an unused variable. D’oh!

The example in the “Efficient” book that triggered our discussion is provided here:

The authors go on to state:

Only the first form of initialization is guaranteed, across compiler implementations, not to generate a temporary object. If you use forms 2 or 3, you may end up with a temporary, depending on the compiler implementation. In practice, however, most compilers should optimize the temporary away, and the three initialization forms presented here would be equivalent in their efficiency.

Ever since I read that book many years ago, I’ve always preferred to use the “function” style initialization over the “assignment” style. But it’s just a personal preference.

A Real Renaissance

For quite some time now, I’ve been hearing that C++ has been undergoing a resurgence of interest; a renaissance. However, until recently, I couldn’t tell if the claim was real, or just some hype coming out of the C++ community to fruitlessly combat the rise of a plethora of new languages.

Well, I’m convinced that the renaissance is legit. The slides below, pilfered from Herb Sutter‘s “The Future Of C++” talk at Microsoft Build 2012, introduced the formation of a new C++ trade group, the “Standard C++ Foundation“.

Note that there are some big guns with deep pockets backing the foundation along with a cadre of brilliant and dedicated directors at the helm.

It’s a good time to be a C++ programmer, so join the renaissance and start learning the new features and libraries offered up in C++11. Of course, if your technical management is not forward looking and it’s tight with training dollars, you’ll have to do it on your own time, covertly, behind the scenes. But it will not only be fun, it will enhance your marketability.

The C++ Product Roadmap

Fresh from the ISO C++ chairman himself, Herb Sutter, I present you with the C++ product roadmap:

If all goes according to plan, a minor release of the ISO standard will be hatched in 2014. By minor, Herb means that it will be mostly bug fixes to C++11, plus a filesystem library based on Boost.org‘s brilliant work. The networking library, which is big and being developed by a large group of smart people, will be hatched incrementally in a series of Technical Specifications (TS).

The main point that Herb stressed when he hoisted the slide was that “the past is not a good predictor of the future“. If all goes according to plan, the time between major releases of the standard will have been cut from 13 years to 6.

Misapplication Of Partially Mastered Ideas

Because the time investment required to become proficient with a new, complex, and powerful technology tool can be quite large, the decision to design C++ as a superset of C was not only a boon to the language’s uptake, but a boon to commercial companies too – most of whom developed their product software in C at the time of C++’s introduction. Bjarne Stroustrup‘s decision killed those two birds with one stone because C++ allowed a gradual transition from the well known C procedural style of programming to three new, up-and-coming mainstream styles at the time: object-oriented, generic, and abstract data types. As Mr. Stroustrup says in D&E:

Companies simply can’t afford to have significant numbers of programmers unproductive while they are learning a new language. Nor can they afford projects that fail because programmers over enthusiastically misapply partially mastered new ideas.

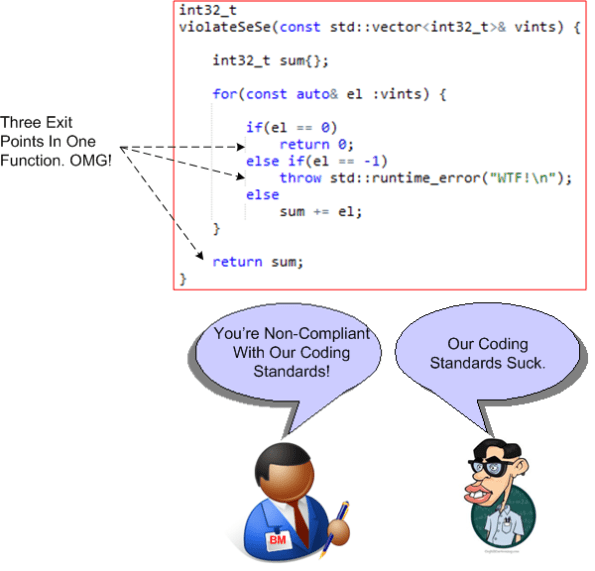

That last sentence in Bjarne’s quote doesn’t just apply to programming languages, but to big and powerful libraries of functionality available for a language too. It’s one challenge to understand and master a language’s technical details and idioms, but another to learn network programming APIs (CORBA, DDS, JMS, etc), XML APIs, SQL APIs, GUI APIs, concurrency APIs, security APIs, etc. Thus, the investment dilemma continues:

I can’t afford to continuously train my programming workforce, but if I don’t, they’ll unwittingly implement features as mini booby traps in half-learned technologies that will cause my maintenance costs to skyrocket.

BD00 maintains that most companies aren’t even aware of this ongoing dilemma – which gets worse as the complexity and diversity of their product portfolio rises. Because of this innocent, but real, ignorance:

- they don’t design and implement continuous training plans for targeted technologies,

- they don’t actively control which technologies get introduced “through the back door” and get baked into their products’ infrastructure; receiving in return a cacophony of duplicated ways of implementing the same feature in different code bases.

- their software maintenance costs keep rising and they have no idea why; or they attribute the rise to insignificant causes and “fix” the wrong problems.

I hate when that happens. Don’t you?

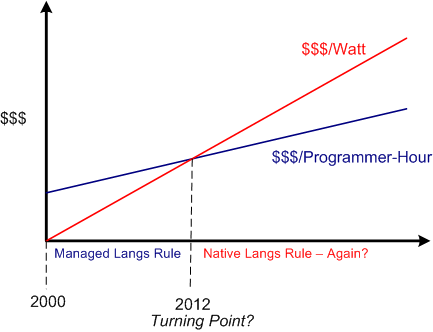

Performance Per Watt

Recently, I concocted a blog post on Herb Sutter‘s assertion that native languages are making a comeback due to power costs usurping programming labor costs as the dominant financial drain in software development. It seems that the writer of this InforWorld post seems to agree:

But now that Intel has decided to focus on performance per watt, as opposed to pure computational performance, it’s a very different ball game. – Bill Snyder

Since hardware developers like Intel have shifted their development focus towards performance per watt, do you think software development orgs will follow by shifting from managed languages (where the minimization of labor costs is king) to native languages (where the minimization of CPU and memory usage is king)?

Hell, I heard Facebook chief research scientist Andrei Alexandrescu (admittedly a native language advocate (C++ and D)) mention the never-used-before “users per watt” metric in a recent interview. So, maybe some companies are already onboard with this “paradigm shift“?

Hacrobatics

It’s funny how attitudes, preferences, and likes-dislikes change over time via personal experience and the acquisition of new knowledge. Having transitioned from a C background over to C++ quite awhile ago, I used to think pre-processor macros were a kool feature that came along for the ride. However, after having been burned multiple times by scope-ignoring macros, I learned to hate the damn little buggers. The scorchings made me fully appreciate the addition of “const“, templates, and inline functions to C++ in order to wean people off of “hacros“.

Maintaining a “hacro” laced program can drive anyone up a wall because:

I’m bummed, but not surprised, at how many people still think that “hacros” are a kool and useful feature of C++.

New Native Languages

The editor of Dr. Dobb’s Journal, Andrew Binstock, has put together a nice little slideshow summary of four “modern” native (native = no virtual machine running underneath the code) programming languages here: New Native Languages. As the figure below shows, these relatively new languages are D, Go, Vala, and Rust.

According to Andy, “older” native languages like C11 and C++11 “can have the feel of a past era onto which contemporary elements have been grafted“. I don’t agree with his “grafted” assertion, but I have to begrudgingly agree with him when he says:

The upshot is that to be truly expert in C++ requires far more education and far more effort than comparable mainstream OO languages (notably, Java and C#). – Andrew Binstock

Since I have much admiration for “D” creator Walter Bright and co-evolver Andrei Alexandrescu, I’ve been following the evolution of their language from afar. These two guys really know C++ inside and out; warts and all. Thus, unlike the 1995 Sun marketing proclamation that “Java is what C++ should have been“, Walter and Andrei are truly evolving D into “what C++ should be” – which is not just an OO language. Plus, they are being very gracious about it.