Archive

Generating NaNs

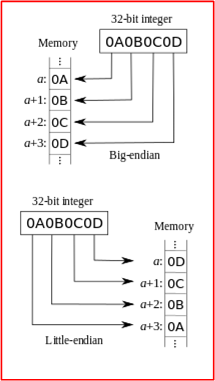

While converting serialized double precision floating point numbers received in a datagram over a UDP socket into a native C++ double type, I kept getting NaN values (Not a Number) whenever I used the deserialized version of the number in a numeric computation. Of course, the problem turned out to be the well-known “Endian” issue where one machine represents numbers internally in Big Endian format and the other uses Little Endian format.

One way of creating a NaN is by taking the square root of a negative number. Another way is to jumble up the bytes in a float or double such that an illegal bit pattern is produced. Uncompensated Endian mismatches between machines can easily produce illegal bit patterns that create NaNs. Note that NaNs are only an issue in the floating point types because every conceivable bit pattern stored in an integral type is always legal.

To prove just how easy it is to produce a NaN by jumbling up the bytes in a double, I wrote this little program that I’d like to share:

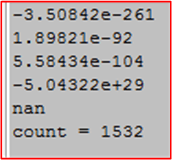

Here is a fragment of the output from a typical program run:

I was a little surprised at the low number of iterations it typically takes to produce a NaN, but that’s a good thing. If it takes millions of iterations, it may be hard to trace a bug back to a NaN problem.

For those who would try this program out, here is a copy-paste version of the code:

#include <cstdint>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <cmath>

int main() {

//Determine the number of bytes in a double

const int32_t numBytesInDouble{sizeof(double)};

//Create a fixed-size buffer that holds the number of bytes

//in a double

int8_t buffer[numBytesInDouble];

//Setup a random number generator to produce

//a uniformly distributed int8_t value

std::random_device rd{};

std::mt19937 gen{rd()};

std::uniform_int_distribution<int8_t> dis{-128, 127};

//interpret the buffer as a double*

const double* dp{reinterpret_cast<double*>(buffer)};

int32_t count{-1};

do{

//fill our buffer with random valued bytes

for(int32_t i=0; i<numBytesInDouble; ++i) {

buffer[i] = dis(gen);

}

std::cout << *dp << "\n";

++count;

}while(not std::isnan(*dp));

std::cout << "count = " << count << "\n";

}

M Of N Fault Detection

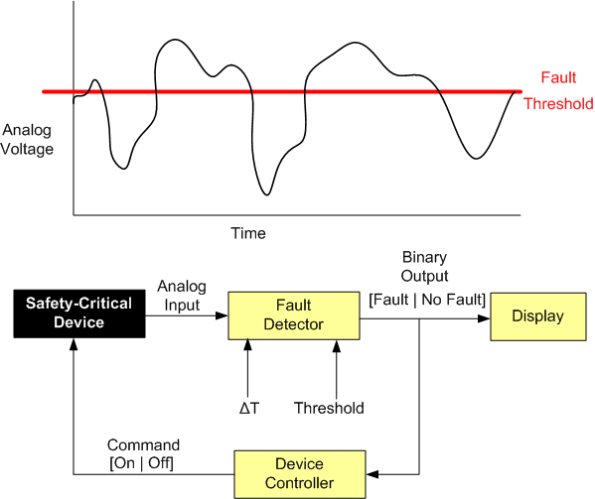

Let’s say that, for safety reasons, you need to monitor the voltage (or some other dynamically changing physical attribute) of a safety-critical piece of equipment and either shut it down automatically and/or notify someone in the event of a “fault“.

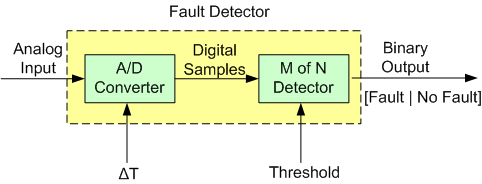

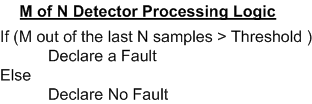

The figure below drills into the next level of detail of the Fault Detector. First, the analog input signal is digitized every ΔT seconds and then the samples are processed by an “M of N Detector”.

The logic implemented in the Detector is as follows:

Instead of “crying wolf” and declaring a fault each time the threshold is crossed (M == N == 1), the detector, by providing the user with the ability to choose the values of M and N, provides the capability to smooth out spurious threshold crossings.

The next figure shows an example input sequence and the detector output for two configurations: (M == N == 4) and (M == 2, N == 4).

Finally, here’s a c++ implementation of an M of N Detector:

#ifndef MOFNDETECTOR_H_

#define MOFNDETECTOR_H_

#include <cstdint>

#include <deque>

class MofNDetector {

public:

MofNDetector(double threshold, int32_t M, int32_t N) :

_threshold(threshold), _M(M), _N(N) {

reset();

}

bool detectFault(double sample) {

if (sample > _threshold)

++_numCrossings;

//Add our newest sample to the history

if(sample > _threshold)

_lastNSamples.push_back(true);

else

_lastNSamples.push_back(false);

//Do we have enough history yet?

if(static_cast<int32_t>(_lastNSamples.size()) < _N) {

return false;

}

bool retVal{};

if(_numCrossings >= _M)

retVal = true;

//Get rid of the oldest sample

//to make room for the next one

if(_lastNSamples.front() == true)

--_numCrossings;

_lastNSamples.pop_front();

return retVal;

}

void reset() {

_lastNSamples.clear();

_numCrossings =0;

}

private:

int32_t _numCrossings;

double _threshold;

int32_t _M;

int32_t _N;

std::deque<bool> _lastNSamples{};

};

#endif /* MOFNDETECTOR_H_ */

Linear Interpolation In C++

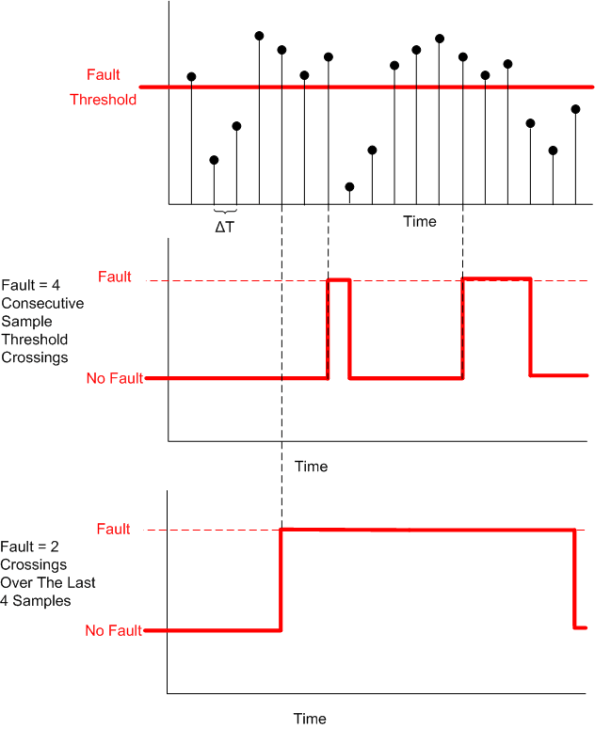

In scientific programming and embedded sensor systems applications, linear interpolation is often used to estimate a value from a series of discrete data points. The problem is stated and the solution is given as follows:

The solution assumes that any two points in a set of given data points represents a straight line. Hence, it takes the form of the classic textbook equation for a line, y = b + mx, where b is the y intercept and m is the slope of the line.

If the set of data points does not represent a linear underlying phenomenon, more sophisticated polynomial interpolation techniques that use additional data points around the point of interest can be utilized to get a more accurate estimate.

The code snippets below give the definition and implementation of a C++ functor class that performs linear interpolation. I chose to use a vector of pairs to represent the set of data points. What would’ve you used?

Interpolator.h

#ifndef INTERPOLATOR_H_

#define INTERPOLATOR_H_

#include <utility>

#include <vector>

class Interpolator {

public:

//On construction, we take in a vector of data point pairs

//that represent the line we will use to interpolate

Interpolator(const std::vector<std::pair<double, double>>& points);

//Computes the corresponding Y value

//for X using linear interpolation

double findValue(double x) const;

private:

//Our container of (x,y) data points

//std::pair::<double, double>.first = x value

//std::pair::<double, double>.second = y value

std::vector<std::pair<double, double>> _points;

};

#endif /* INTERPOLATOR_H_ */

Interpolator.cpp

#include "Interpolator.h"

#include <algorithm>

#include <stdexcept>

Interpolator::Interpolator(const std::vector<std::pair<double, double>>& points)

: _points(points) {

//Defensive programming. Assume the caller has not sorted the table in

//in ascending order

std::sort(_points.begin(), _points.end());

//Ensure that no 2 adjacent x values are equal,

//lest we try to divide by zero when we interpolate.

const double EPSILON{1.0E-8};

for(std::size_t i=1; i<_points.size(); ++i) {

double deltaX{std::abs(_points[i].first - _points[i-1].first)};

if(deltaX < EPSILON ) {

std::string err{"Potential Divide By Zero: Points " +

std::to_string(i-1) + " And " +

std::to_string(i) + " Are Too Close In Value"};

throw std::range_error(err);

}

}

}

double Interpolator::findValue(double x) const {

//Define a lambda that returns true if the x value

//of a point pair is < the caller's x value

auto lessThan =

[](const std::pair<double, double>& point, double x)

{return point.first < x;};

//Find the first table entry whose value is >= caller's x value

auto iter =

std::lower_bound(_points.cbegin(), _points.cend(), x, lessThan);

//If the caller's X value is greater than the largest

//X value in the table, we can't interpolate.

if(iter == _points.cend()) {

return (_points.cend() - 1)->second;

}

//If the caller's X value is less than the smallest X value in the table,

//we can't interpolate.

if(iter == _points.cbegin() and x <= _points.cbegin()->first) {

return _points.cbegin()->second;

}

//We can interpolate!

double upperX{iter->first};

double upperY{iter->second};

double lowerX{(iter - 1)->first};

double lowerY{(iter - 1)->second};

double deltaY{upperY - lowerY};

double deltaX{upperX - lowerX};

return lowerY + ((x - lowerX)/ deltaX) * deltaY;

}

In the constructor, the code attempts to establish the invariant conditions required before any post-construction interpolation can be attempted:

- It sorts the data points in ascending X order – just in case the caller “forgot” to do it.

- It ensures that no two adjacent X values have the same value – which could cause a divide-by-zero during the interpolation computation. If this constraint is not satisfied, an exception is thrown.

Here are the unit tests I ran on the implementation:

#include "catch.hpp"

#include "Interpolator.h"

TEST_CASE( "Test", "[Interpolator]" ) {

//Construct with an unsorted set of data points

Interpolator interp1{

{

//{X(i),Y(i)

{7.5, 32.0},

{1.5, 20.0},

{0.5, 10.0},

{3.5, 28.0},

}

};

//X value too low

REQUIRE(10.0 == interp1.findValue(.2));

//X value too high

REQUIRE(32.0 == interp1.findValue(8.5));

//X value in 1st sorted slot

REQUIRE(15.0 == interp1.findValue(1.0));

//X value in last sorted slot

REQUIRE(30.0 == interp1.findValue(5.5));

//X value in second sorted slot

REQUIRE(24.0 == interp1.findValue(2.5));

//Two points have the same X value

std::vector<std::pair<double, double>> badData{

{.5, 32.0},

{1.5, 20.0},

{3.5, 28.0},

{1.5, 10.0},

};

REQUIRE_THROWS(Interpolator interp2{badData});

}

How can this code be improved?

Bidirectionally Speaking

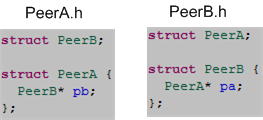

Given a design that requires a bidirectional association between two peer classes:

here is how it can be implemented in C++:

Note: I’m using structs here instead of classes to keep the code in this post less verbose

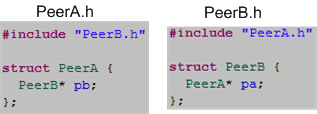

The key to implementing a bidirectional association in C++ is including a forward struct declaration statement in each of the header files. If you try to code the bidirectional relationship with #include directives instead of forward declarations:

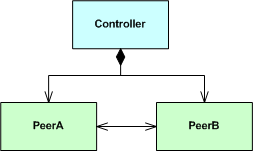

you’ll have unknowingly caused a downstream problem because you’ve introduced a circular dependency into the compiler’s path. To show this, let’s implement the following larger design:

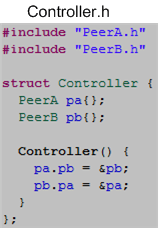

as:

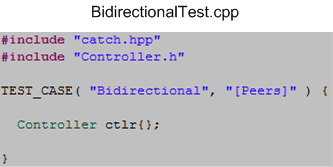

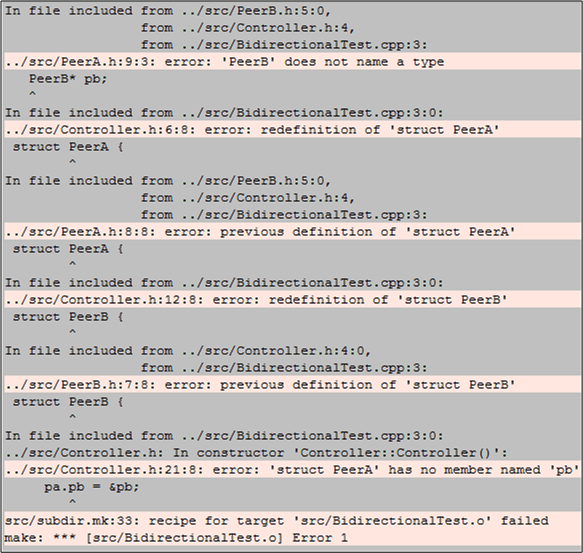

Now, if we try to create a Controller object in a .cpp file like this:

the compiler will be happy with the forward class declarations implementation. However, it will barf on the circularly dependent #include directives implementation. The compiler will produce a set of confusing errors akin to this:

I can’t remember the exact details of the last time I tried coding up a design that had a bidirectional relationship between two classes, but I do remember creating an alternative design that did not require one.

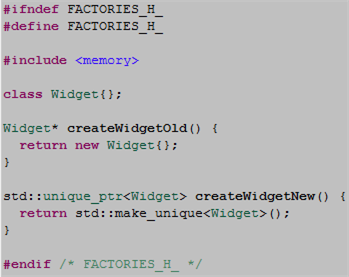

Out With The Old, In With The New

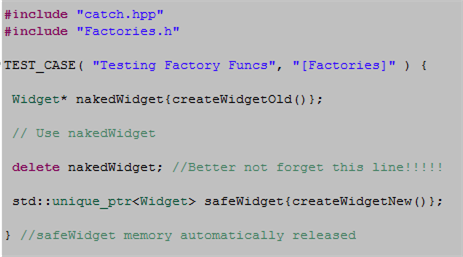

In “old” C++, object factories had little choice but to return unsafe naked pointers to users. In “new” C++, factories can return safe smart pointers. The code snippet below contrasts the old with new.

The next code snippet highlights the difference in safety between the old and the new.

When a caller uses the old factory technique, safety may be compromised in two ways:

- If an exception is thrown in the caller’s code after the object is created but before the delete statement is executed, we have a leak.

- If the user “forgets” to write the delete statement, we have a leak.

Returning a smart pointer from a factory relegates these risks to the dust bin of history.

Publicizing My Private Parts

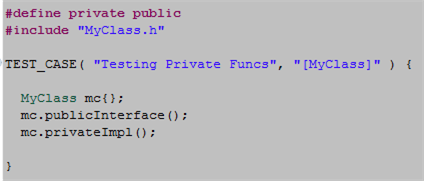

Check out the simple unit test code fragment below. What the hell is the #define private public preprocessor directive doing in there?

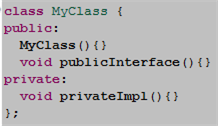

Now look at the simple definition of MyClass:

The purpose of the preprocessor #define statement is to provide a simple, elegant way of being able to unit test the privately defined MyClass::privateImpl() function. It sure beats the kludgy “friend class technique” that blasphemously couples the product code base to the unit test code base, no? It also beats the commonly abused technique of specifying all member functions as public for the sole purpose of being able to invoke them in unit test code, no?

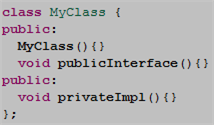

Since the (much vilified) C++ preprocessor is a simple text substitution tool, the compiler sees this definition of MyClass just prior to generating the test executable:

Embarassingly, I learned this nifty trick only recently from a colleague. Even more embarassingly, I didn’t think of it myself.

In an ideal world, there is never a need to directly call private functions or inspect private state in a unit test, but I don’t live in an ideal world. I’m not advocating the religious use of the #define technique to do white box unit testing, it’s just a simple tool to use if you happen to need it. Of course, it would be insane to use it in any production code.

Arne Mertz has a terrific post that covers just about every angle on unit testing C++ code: Unit Tests Are Not Friends.

Politics And C++

It’s Hexed

Prior to the release of C++11 by the ISO WG-21 committee, I followed the development of the standard very closely for several years before it was finally released in 2011. The painfully slow-moving effort to update the language was dubbed “C++0x” because no one knew what year (if any!) the standard would be ratified. Since it wasn’t labeled “C++xx“, everyone was hoping that the year of publication would be 2009 at the latest: “C++09“.

At the time, I stumbled across, and purchased a polo shirt with this comical logo embroidered on the breast:

I can’t remember the year in which I bought the shirt, but it’s obviously at least 6 years old. I still wear it today. Someday, it may be worth a bunch of bitcoins. LOL.

Stack, Heap, Pool: The Prequel

Out of the 1600+ posts I’ve written for this blog over the past 6 years, the “Stack, Heap, Pool” C++ post has gotten the most views out of the bunch. However, since I did not state my motive for writing the post, I think it caused some people to misinterpret the post’s intent. Thus, the purpose of this post is to close that gap of understanding by writing the intro to that post that I should have written. So, here goes…

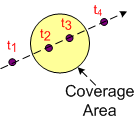

The figure below shows a “target” entering, traversing, and exiting a pre-defined sensor coverage volume.

From a software perspective:

- A track data block that represents the real world target must be created upon detection and entry into the coverage volume.

- The track’s data must be maintained in memory and updated during its journey through the coverage volume. (Thus, the system is stateful at the application layer by necessity.)

- Since the data becomes stale and useless to system users after the target it represents leaves the coverage volume, the track data block must be destroyed upon exit (or some time thereafter).

Now imagine a system operating 24 X 7 with thousands of targets traversing through the coverage volume over time. If the third processing step (controlled garbage collection) is not performed continuously during runtime, then the system has a memory leak. At some point after bootup, the system will eventually come to a crawl as the software consumes all the internal RAM and starts thrashing from swapping virtual memory to/from off-processor, mechanical, disk storage.

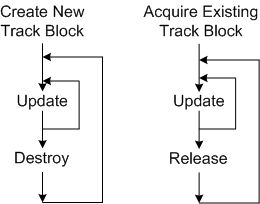

In C++, there are two ways of dynamically creating/destroying objects during runtime:

- Allocating/deallocating objects directly from the heap using standard language facilities (new+delete (don’t do this unless you’re stuck in C++98/03 land!!!), std::make_shared, or, preferably, std::make_unique)

- Acquiring/releasing objects indirectly from the heap using a pool of memory that is pre-allocated from said heap every time the system boots up.

Since the object’s data fields must be initialized in both techniques, initialization time isn’t a factor in determining which method is “faster“. Finding a block of memory the size of a track object is the determining factor.

As the measurements I made in the “Stack, Heap, Pool” post have demonstrated, the pool “won” the performance duel over direct heap allocation in this case because it has the advantage that all of its entries are the exact same size of a track object. Since the heap is more general purpose than a pool, the use of an explicit or implicit “new” will generally make finding an appropriately sized chunk of memory in a potentially fragmented heap more time consuming than finding one in a finite, fixed-object-size, pool. However, the increased allocation speed that a pool provides over direct heap access comes with a cost. If the number of track objects pre-allocated on startup is less than the peak number of targets expected to be simultaneously present in the coverage volume at any one instant, then newly detected targets will be discarded because they can’t “fit” into the system – and that’s a really bad event when users are observing and directing traffic in the coverage volume. There is no such thing as a free lunch.

The Problem, The Culprits, The Hope

The Problem

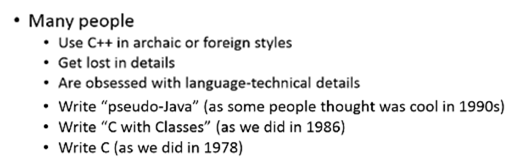

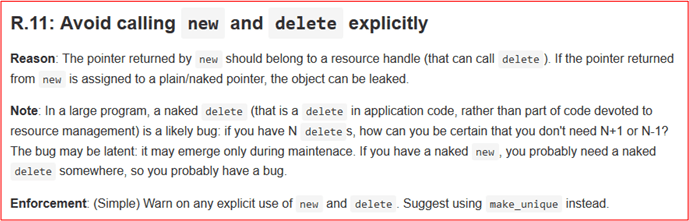

Bjarne Stroustrup’s keynote speech at CppCon 2015 was all about writing good C++11/14 code. Although “modern” C++ compilers have been in wide circulation for four years, Bjarne still sees:

I’m not an elite, C++ committee-worthy, programmer, but I can relate to Bjarne’s frustration. Some time ago, I stumbled upon this code during a code review:

class Thing{};

std::vector<Thing> things{};

const int NUM_THINGS{2000};

for(int i=0; i<NUM_THINGS; ++i)

things.push_back(*(new Thing{}));

Upon seeing the naked “new“, I searched for a matching loop of “delete“s. Since I did not find one, I ran valgrind on the executable. Sure enough, valgrind found the memory leak. I flagged the code as having a memory leak and suggested this as a less error-prone substitution:

class Thing{};

std::vector<Thing> things{};

const int NUM_THINGS{2000};

for(int i=0; i<NUM_THINGS; ++i)

things.push_back(Thing{});

Another programmer suggested an even better, loopless, alternative:

class Thing{};

std::vector<Thing> things{};

const int NUM_THINGS{2000};

things.resize(NUM_THINGS);

Sadly, the author blew off the suggestions and said that he would add the loop of “delete“s to plug the memory leak.

The Culprits

A key culprit in keeping the nasty list of bad programming habits alive and kicking is that…

Confused, backwards-looking teaching is (still) a big problem – Bjarne Stroustrup

Perhaps an even more powerful force keeping the status quo in place is that some (many?) companies simply don’t invest in their employees. In the name of fierce competition and the never-ending quest to increase productivity (while keeping wages flat so that executive bonuses can be doled out for meeting arbitrary numbers), these 20th-century-thinking dinosaurs micro-manage their employees into cranking out code 8+ hours a day while expecting the workforce to improve on their own time.

The Hope

In an attempt to sincerely help the C++ community of over 4M programmers overcome these deeply ingrained, unsafe programming habits, Mr. Stroustrup’s whole talk was about introducing and explaining the “CPP Core Guidelines” (CGC) document and the “Guidelines Support Library” (GSL). In a powerful one-two punch, Herb Sutter followed up the next day with another keynote focused on the CGC/GSL.

The CGC is an open source repository currently available on GitHub. And as with all open source projects, it is a work in progress. The guidelines were hoisted onto GitHub to kickstart the transformation from obsolete to modern programming.

The guidelines are focused on relatively higher-level issues, such as interfaces, resource management, memory management, and concurrency. Such rules affect application architecture and library design. Following the rules will lead to code that is statically type safe, has no resource leaks, and catches many more programming logic errors than is common in code today. And it will run fast – you can afford to do things right. We are less concerned with low-level issues, such as naming conventions and indentation style. However, no topic that can help a programmer is out of bounds.

It’s a noble and great goal that Bjarne et al are striving for, but as the old saying goes, “you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink“. In the worst case, the water is there for the taking, but you can’t even find anyone to lead the horse to the oasis. Nevertheless, with the introduction of the CGC, we at least have a puddle of water in place. Over time, the open source community will grow this puddle into a lake.