Archive

Growth And Development

Two of my favorite bureaucracy-busting systems thinkers, Russell Ackoff and John Warfield, died this year. I’ll miss them both because whenever I’ve read something written by these guys, I always learned something new.

In a tribute to Mr. Ackoff, I’m currently reading Ackoff’s Best: His Classic Writings On Management. One of his off-the-beaten-path insights that he’s passed on to me is the independence between growth and development. Growth is an increase in size or wealth, while development is an increase in capability or competence as a result of learning. According to Ackoff, dumb-ass corpocracies automatically and unquestioningly equate growth with development, and that’s why the vast majority of orgs are obsessed with growth at all costs. Of course, growth and development can, and often do, reinforce each other, but neither is necessary for the other.

Ackoff points out that a system can experience growth without development, and vice versa. A heap of rubbish, or equivalently, a bureaucracy, can grow indefinitely without developing, and artists can develop without growing. If an undeveloped company or company is showered with money, it becomes richer but not more developed. On the other hand, if a well developed company or country is suddenly deprived of wealth, it doesn’t become less developed.

Abstraction

Jeff Atwood, of “Coding Horror” fame, once something like “If our code didn’t use abstractions, it would be a convoluted mess“. As software projects get larger and larger, using more and more abstraction technologies is the key to creating robust and maintainable code.

Using C++ as an example language, the figure below shows the advances in abstraction technologies that have taken place over the years. Each step up the chain was designed to make large scale, domain-specific application development easier and more manageable.

The relentless advances in software technology designed to keep complexity in check is a double-edged sword. Unless one learns and practices using the new abstraction techniques in a sandbox, haphazardly incorporating them into the code can do more damage than good.

One issue is that when young developers are hired into a growing company to maintain legacy code that doesn’t incorporate the newer complexity-busting language features, they become accustomed to the old and unmaintainable style that is encrusted in the code. Because of schedule pressure and no company time allocated to experiment with and learn new language features, they shoe horn in changes without employing any of the features that would reduce the technical debt incurred over years of growing the software without any periodic refactoring. The problem is exacerbated by not having a set of regression tests in place to ensure that nothing gets broken by any major refactoring effort. Bummer.

Requirements Before, Design After

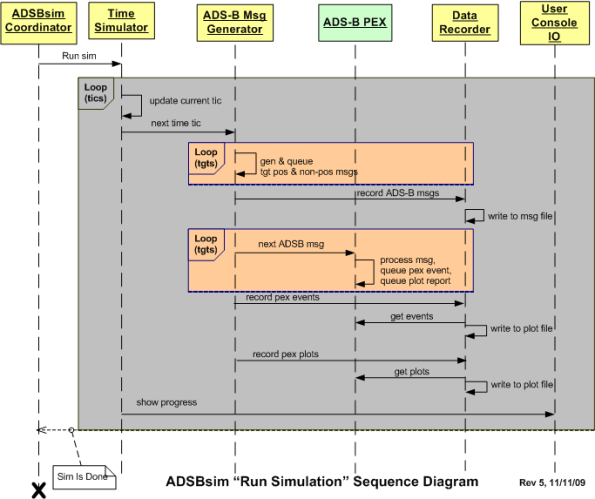

The figure below depicts a UML sequence diagram of the behavior of a simulator during the execution of a user defined scenario. Before the code has been written and tested, one can interpret this diagram as a set of interrelated behavioral requirements imposed on the software. After the code has been written, it can be considered a design artifact that reflects what the code does at a higher level of abstraction than the code itself.

Interpretations like this give credence to Alan Davis’s brilliant quote:

One man’s requirement is another man’s design

Here’s a question. Do you think that specifying the behavior requirements in the diagram would have been best conveyed via a user story or a use case description?

Here’s a question. Do you think that specifying the behavior requirements in the diagram would have been best conveyed via a user story or a use case description?

Culture Adjustment

I think that almost everyone heard about this week’s glitch in the air traffic control system that caused hours of flight delays. Here’s an interesting quote from the government’s GAO (FAA computer failure reflects growing burden on systems — Federal Computer Week):

“However, FAA faces several challenges in fulfilling NextGen’s objectives, including adjusting its culture and business practices, GAO concluded.”

Well, duh. Every mediocre and under performing corpo borg needs to “adjust its culture and business practices”. It’s just that none of them have the competence to do it, regardless of how many titles and credentials that the corpocrats running the show adorn themselves and their sycophants with.

Partial Training

If you’re gonna spend money on training your people, do it right or don’t do it at all.

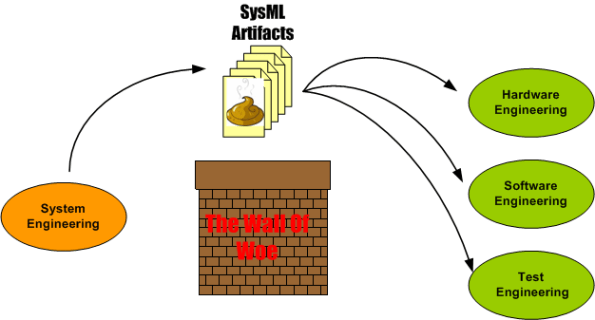

Assume that a new project is about to start up and the corpo hierarchs decide to use it as a springboard to institutionalizing SysML into its dysfunctional system engineering process. The system engineering team is then sent to a 3 day SysML training course where they get sprayed by a fire hose of detailed SysML concepts, terminology, syntax, and semantics.

Armed with their new training, the system engineering team comes back, generates a bunch of crappy, incomplete, ambiguous, and unhelpful SysML artifacts, and then dumps them on the software, hardware, and test teams. The receiving teams, under the schedule gun and not having been trained to read SysML, ignore the artifacts (while pretending otherwise) and build an unmaintainable monstrosity that just barely works – at twice the cost they would would have spent if no SysML was used. The hierarchs, after comparing product development costs before and after SysML training, declare SysML as a failure and business returns to the same old, same old. Bummer.

Under Pressure

Uh oh. One of my favorite companies, the SAS Institute, is under increasing pressure from big, deep pocketed rivals. This NY Times article, Rivals Take Aim at the Software Company SAS – NYTimes.com, elaborates on the details. Since I’m confident that they’ll overcome the competitive threat, that’s not what this post is about. It’s about what the SAS leadership, led by founder, CEO, and PHOR, Jim Goodnight, does to continuously grow and develop both the company and its people. Here are some snippets from the article and this linked-to 60 minutes article that reinforce my faith in the company’s ability to overcome all odds:

There is the subsidized day care and preschool. There are the four company doctors and the dozen nurses who provide free primary care. The recreational amenities include basketball and racquetball courts, a swimming pool, exercise rooms and 40 miles of running and biking trails. There is a meditation garden, as well as on-site haircuts, manicures, and jewelry repair. Employees are encouraged to work 35-hour weeks.

The office atmosphere is sedate. There are no dogs roaming the halls, no Nerf-ball fights, no one jumping on trampolines — no whiff of Silicon Valley. The SAS culture is engineered for its own logic: to reduce distractions and stress, and thus foster creativity.

Employee turnover at SAS averages 4 percent a year, versus about 20 percent for the overall software industry.

SAS has never had a losing year and never laid off a single employee.

“No, we’re not altruistic by any stretch of the imagination. This is a for-profit business and we do all these things because it makes good business sense,” says Jeff Chambers, director of human resources at SAS.

“You know, I guess 95 percent of my assets drive out the front gate every evening,” says Goodnight. “It’s my job to bring them back.”

Academics have studied the company’s benefit-enhanced corporate culture as a model for nurturing creativity and loyalty among engineers and other workers.

SAS invested heavily in research and development, and even today allocates 22 percent of the company’s revenue to research. The formula has paid off in steady growth, year after year. Revenue reached $2.26 billion in 2008, up from $1.34 billion five years earlier.

Unlike many other tech companies, SAS has had no recession-related layoffs this year. “I’ve got a two-year pipeline of projects in R & D,” Mr. Goodnight says. “Why would I lay anyone off?”

Mr. Goodnight recalls those days as a brief period of New Economy surrealism, and going public as a path wisely avoided. SAS, he says, is a culture averse to the short-term pressures of Wall Street, which he characterizes as “a bunch of 28-year-olds, hunched over spreadsheets, trying to tell you how to run your business.”

Goodnight says it’s pressure from Wall Street to please shareholders by delivering rising quarterly earnings that has poisoned the corporate well.

Mr. Goodnight, though 66, has no plans to retire himself. His fingerprints, colleagues say, remain all over the business, especially in meeting with customers and in overseeing research.

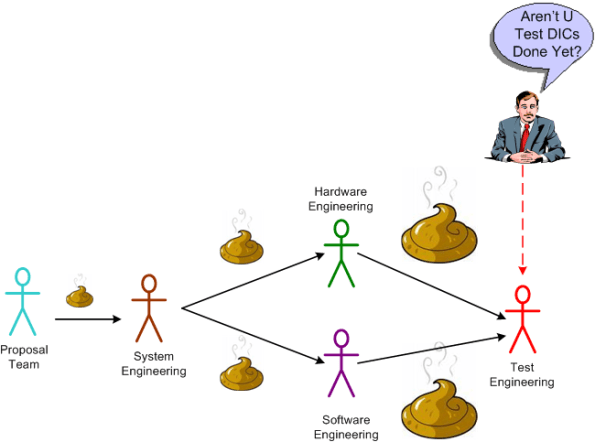

Poor Test Dudes

Out of all the types of DICs in a textbook CCH, the poor test dudes always have the roughest go of it. Out of necessity, they have mastered the art of nose pinching.

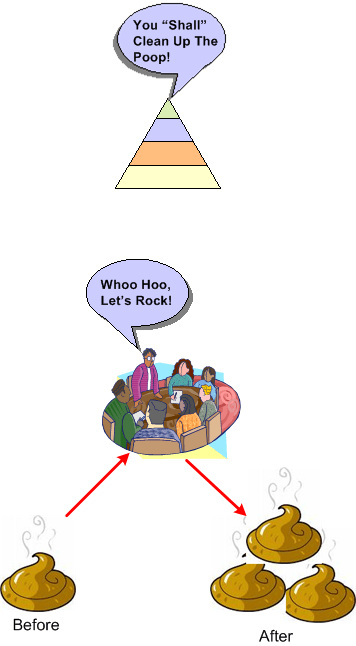

A Flurry Of Activity

It’s always fun to watch the initial stages of euphoria emerge and then disappear when a corpo-wide initiative that’s intended to improve performance is attempted. The anointed “design” team, which is almost always filled exclusively with managers and overhead personnel who conveniently won’t have to implement the behavioral changes that they poop out of the initiative themselves, starts out full of energy and bright ideas on how to solve the performance problem. After the kickoff, a resource-burning flurry of activity ensues, with meeting after meeting, discussion after discussion, and action item after action item being tossed left and right. When the money’s gone, the time’s gone, and the smoke clears, business returns to the same old, same old.

As a hypothetical example, assume that an initiative to institute a metrics program throughout the org has been mandated from the heavens. At best, after spending a ton of money and time working on the issue, the anointed design team generates a long list of complicated metrics that “someone else” is required to collect, analyze, and act upon. The team then declares victory and self-congratulatory pats on the back abound. At worst, the team debates the issue for a few meetings, conveniently forgets it, and then moves on to some other initiative – hoping that no one notices the useless camouflage that they left in their wake. Bummer.

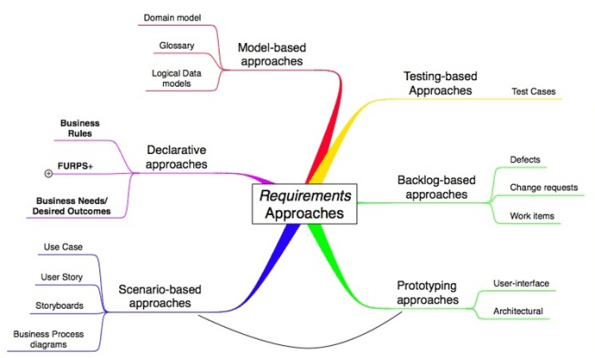

The Requirements Landscape

Kurt Bittner, of Ivar Jacobson International, has written a terrific white paper on the various approaches to capturing requirements. The mind map below was copied and pasted from Kurt’s white paper.

In his paper, Bittner discusses the pluses and minuses of each of his defined approaches. For the text-based “declarative” approaches, he states the pluses as: “they are familiar” and “little specialized training” is needed to write them. Bittner states the minuses as:

- They are “poor at specifying flow behavior”

- It’s “hard to connect related requirements”

IMHO, as systems get more and more complex, these shortcomings lead to bigger and bigger schedule, cost, and quality shortfalls. Yet, despite the advances in requirements specification methodologies nicely depicted in Bittner’s mind map, defense/aerospace contractors and their bureaucratic government customers seem to be forever married to the text-based “shall” declarative approach of yesteryear. Dinosaur mindsets, the lack of will to invest in corpo-wide training, and expensive past investments in obsolete and entrenched text-based requirements tools have prevented the newer techniques from gaining much traction. Do you think this encrusted way of specifying requirements will change anytime soon?

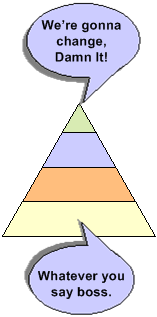

We Promise To Change, And We Really Mean It This Time

GM is a classic example of a toxic Command and Control Hierarchical (CCH) corpocracy. In this NY Times article, the newly anointed hierarchs and their spin doctors promise that “things will be different” in the future. Uh, OK. If you say so.

According to corpo insiders, here’s the way things were.

…employees were evaluated according to a “performance measurement process” that could fill a three-ring binder.

“We measured ourselves ten ways from Sunday,” he said. “But as soon as everything is important, nothing is important.”

Decisions were made, if at all, at a glacial pace, bogged down by endless committees, reports and reviews that astonished members of President Obama’s auto task force.

“Have we made some missteps? Yes,” said Susan Docherty, who last month was promoted to head of United States sales. “Are we going to slip back to our old ways? No.”

G.M.’s top executives prized consensus over debate, and rarely questioned its elaborate planning processes. A former G.M. executive and consultant, Rob Kleinbaum, said the culture emphasized past glories and current market share, rather than focusing on the future.

“Those values were driven from the top on down,” said Mr. Kleinbaum. “And anybody inside who protested that attitude was buried.”

In the old G.M., any changes to a product program would be reviewed by as many as 70 executives, often taking two months for a decision to wind its way through regional forums, then to a global committee, and finally to the all-powerful automotive products board.

“In the past, we might not have had the guts to bring it up,” said Mr. Reuss. “No one wanted to do anything wrong, or admit we needed to do a better job.”

In the past, G.M. rarely held back a product to add the extra touches that would improve its chances in a fiercely competitive market.

“If everybody is afraid to do anything, do we have a chance of winning?” Mr. Stephens said in one session last month.

The vice president would say, ‘I got here because I’m a better engineer than you, and now I’m going to tell you how bad a job you did.’ ”

The Aztek was half-car, half-van, and universally branded as one of the ugliest vehicles to ever hit the market. … but his job required him to defend it as if it were a thing of beauty.

Here’s what they’re doing to change their culture of fear, malaise, apathy, and mediocrity:

G.M.’s new chairman, Edward Whitacre Jr., and directors have prodded G.M. to cut layers of bureaucracy, slash its executive ranks by a third, and give broad, new responsibilities to a cadre of younger managers.

Replacing a binder full of job expectations with a one-page set of goals is just one sign of the fresh start, said Mr. Woychowski.

Mr. Lauckner came up with a new schedule that funneled all product decisions to weekly meetings of an executive committee run by Mr. Henderson and Thomas Stephens, the company’s vice chairman for product development.

Mr. Stephens has been leading meetings with staff members called “pride builders.” The goal, he said, was to increase the “emotional commitment” to building better cars and encourage people to speak their minds.

“But now we need to be open and transparent and trust each other, and be honest about our strengths and weaknesses.”

So, what do you think? Do you think that these “creative” CCH dissolving solutions and others like them will do the trick? Do you think they’ll pull it off? Is it time to invest in the “new” GM’s stock?