Archive

Apples And Oranges

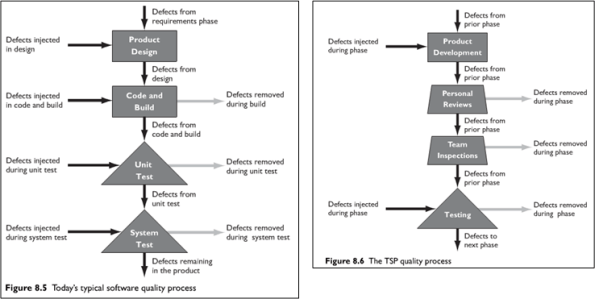

In “Leadership, Teamwork, and Trust“, Watts Humphrey and James Over build a case against the classic “Test To Remove Defects” mindset (see the left portion of the figure below). They assert that testing alone is not enough to ensure quality – especially as software systems grow larger and commensurately more complex. Their solution to the problem (shown on the right of the figure below) calls for more reviews and inspections, but I’m confused as to when they’re supposed to occur: before, after, or interwoven with design/coding?

If you compare the left and right hand sides of the figure, you may have come to the same conclusion as I have: it seems like an apples to oranges comparison? The left portion seems more “concrete” than the right portion, no? Since they’re not enumerated on the right, are the “concrete” design and code/build tasks shown on the left subsumed within the more generic “Product Development” box on the right?

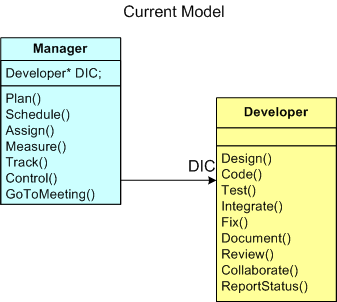

In order to un-confuse myself, I generated the equivalent of the Humphrey/Over TSP (Team Software Process) quality process diagram on the right using the diagram on the left as the starting reference point. Here’s the resulting apples-to-apples comparison:

If this is what Humphrey and Over meant, then I’m no longer confused. Their TSP approach to software quality is to supplement unit and system testing with reviews and inspections before testing occurs. I wish they said that in the first place. Maybe they did, but I missed it.

If this is what Humphrey and Over meant, then I’m no longer confused. Their TSP approach to software quality is to supplement unit and system testing with reviews and inspections before testing occurs. I wish they said that in the first place. Maybe they did, but I missed it.

Exaggerated And Distorted

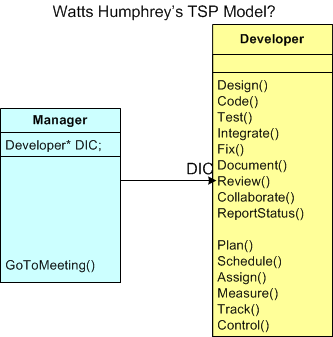

The figure below provides a UML class diagram (“class” is such an appropriate word for this blarticle) model of the Manager-Developer relationship in most software development orgs around the globe. The model is so ubiquitous that you can replace the “Developer” class with a more generic “Knowledge Worker” class. Only the Code(), Test(), and Integrate() behaviors in the “Developer” class need to be modified for increased global applicability.

Everyone knows that this current model of developing software leads to schedule and cost overruns. The bigger the project, the bigger the overruns. D’oh!

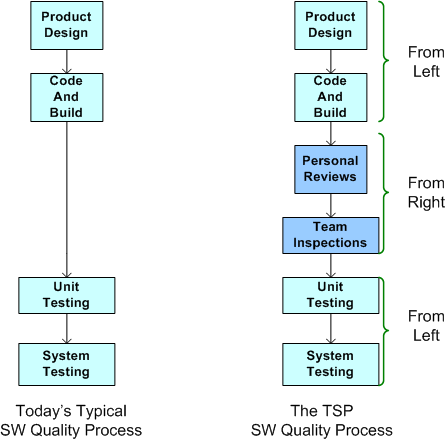

In this article and this interview, Watts Humphrey trumps up his Team Software Process (TSP) as the cure for the disease. The figure below depicts an exaggerated and distorted model of the manger-developer relationship in Watts’s TSP. Of course, it’s an exaggerated and distorted view because it sprang forth from my twisted and tortured mind. Watts says, and I wholeheartedly agree (I really do!), that the only way to fix the dysfunction bred by the current way of doing things is to push the management activities out of the Manager class and down into the Developer class (can you say “empowerment”, sic?). But wait. What’s wrong with this picture? Is it so distorted and exaggerated that there’s not one grain of truth in it? Decide for yourself.

Even if my model is “corrected” by Watts himself so that the Manager class actually adds value to the revolutionary TSP-based system, do you think it’s pragmatically workable in any org structured as a CCH? Besides reallocating the control tasks from Manager to Developer, is there anything that needs to socially change for the new system to have a chance of decreasing schedule and cost overruns (hint: reallocation of stature and respect)? What about the reward and compensation system? Does that need to change (hint: increased workload/responsibility on one side and decreased workload/responsibility on the other)? How many orgs do you know of that aren’t structured as a crystalized CCH?

Strangely (or not?), Watts doesn’t seem to address these social system implications of his TSP. Maybe he does, but I just haven’t seen his explanations.

Double Whammy

Five Principles

Watts Humphrey is perhaps the most decorated and credentialed member of the software engineering community. Even though his project management philosophy is a tad too rigidly disciplined for me, the dude is 83 years young and he has obtained eons of experience developing all kinds of big, scary, software-intensive systems. Thus, he’s got a lot of wisdom to share and he’s definitely worth listening to.

In “Why Can’t We Manage Large Projects?“, Watts lists the following principles as absolutely necessary for the prevention of major cost and time overruns on knowledge-intensive projects – big and small.

Since nobody’s perfect (except for me — and you?), all tidy packages of advice contain both fluff and substance. The 5 point list above is no different. Numbers 1, 4 and 5, for example, are real motherhood and apple pie yawners – no? However, numbers 2 and 3 contain some substance.

Trustworthy Teams

Number 2 is intriguing to me because it moves the screwup spotlight away from the usual suspects (BMs of course), and onto the DICforce. Watt’s (rightly) says that DIC-teams must be willing to manage themselves. Later in his article, Watts states:

To truly manage themselves, the knowledge workers… must be held responsible for producing their own plans, negotiating their own commitments, and meeting these commitments with quality products.

Now, here’s the killer double whammy:

Knowledge worker DIC-types don’t want to do management work (planning, measuring, watching, controlling, evaluating), and BMs don’t want to give it up to them. – Bulldozer00

Besides disliking the nature of the work, the members of the DICforce know they won’t be rewarded or given higher status in the hierarchy for taking on the extra workload of planning, measuring, and status taking. Adding salt to the wound, BMs won’t give up their PWCE “job” responsibilities because then it would (rightfully) look like they’re worthless to their bosses in the new scheme of things. Bummer, no?

Facts And Data

As long as orgs remain structured as stratified hierarchies (which for all practical purposes will be forever unless an act of god occurs), Watts’s noble number 3 may never take hold. Ignoring facts/data and relying on seniority/status to make decisions is baked into the design of CCHs, and it always will be.

It’s the structure, stupid! – Bulldozer00