Archive

Benevolent Dictators And Unapologetic Aristocrats

The Editor in Chief of Dr. Dobb’s Journal, Andrew Binstock, laments about the “committee-ization” of programming languages like C, C++, and Java in “In Praise of Benevolent Language Dictators“:

Where the vision (of the language) is maintained by a single individual, quality thrives. Where committees determine features, quality declines inexorably: Each new release saps vitality from the language even as it appears to remedy past faults or provide new, awaited capabilities.

I think Andrew’s premise applies not only to languages, but it also applies to software designs, architectures, and even organizations of people. These constructs are all “systems” of dynamically interacting elements wired together in order to realize some purpose – not just bags of independent parts. As an example, Fred Brooks, in his classic book, “The Mythical Man-Month“, states:

To achieve conceptual integrity, a design must proceed from one mind or a small group of agreeing minds.

If a system is to have conceptual integrity, someone must control the concepts. That is an aristocracy that needs no apology.

The greater the number of people involved in a concerted effort, the lower the coherency within, and the lower the consistency across, the results. That is, unless a benevolent dictator or unapologetic aristocrat is involved AND he/she is allowed to do what he/she decides must be done to ensure that conceptual integrity is preserved for the long haul.

Of course, because of the relentless increase in entropy guaranteed by the second law of thermodynamics, all conceptually integrated “closed systems” eventually morph into a disordered and random mess of unrelated parts. It’s just a matter of when, but if an unapologetic aristocrat who is keeping the conceptual integrity of a system intact leaves or is handcuffed by clueless dolts who have power over him/her, the system’s ultimate demise is greatly accelerated.

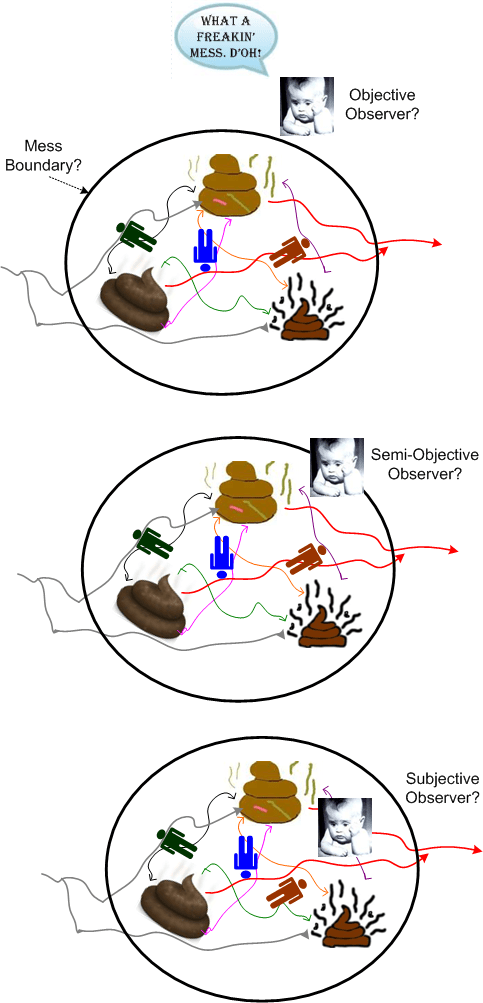

Tainted Observations

Based on his rudimentary understanding of quantum physics, BD00 thinks there is no such thing as a truly objective observer. Every observation is tainted by the instantaneous and unconscious coupling of personal (a.k.a subjective) beliefs, desires, and fears to the observed. The closer one is to a perceived “mess“, the more the taint.

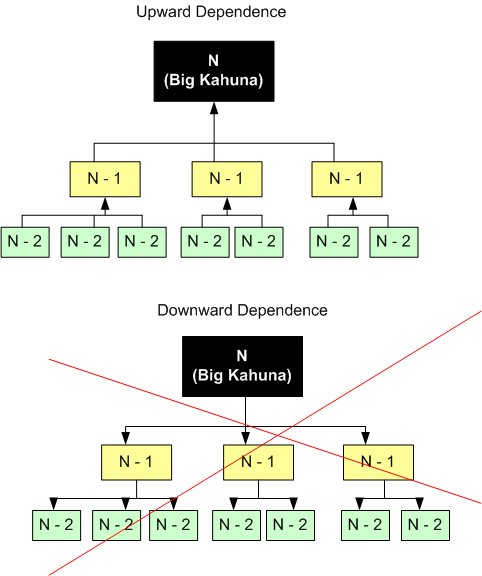

Downward Dependence

Almost everybody knows about, and behaves in accordance with, the concept of “Upward Dependence“. You know, the hapless dependence of the many toiling in the lower levels of a hierarchically structured org upon the few in the higher levels for financial, psychological and, in extreme cases (e.g. despot-commandeered governments), physical health. However, in CLORGs and DYSCOs, the reality of “Downward Dependence” is willfully ignored in the minds of the DICforce and the SCOLs who rule over them.

The term “Downward Dependence” captures the fact that the health of the whole org, which obviously includes its upper echelons, depends heavily on the quality and efficiency of the work performed in the lower tiers. As a minimum, a recognition of the reality of “Downward Dependence” requires:

- humility on the part of SCOLs

- assertiveness on the part of DICsters

In viable and cutting edge orgs, these behaviors are on display daily, but not in CLORGs or DYSCOs. In these types of monstrosities, the 18th century reward and punishment system they utilize requires the org’s SCOLs to don masks of infallibility and its DICs to be unassertive – regardless of whether the participants know it or not. Bummer for the “whole“, no?

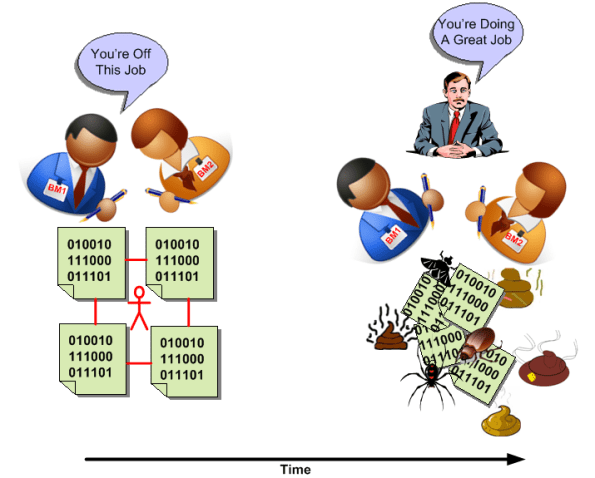

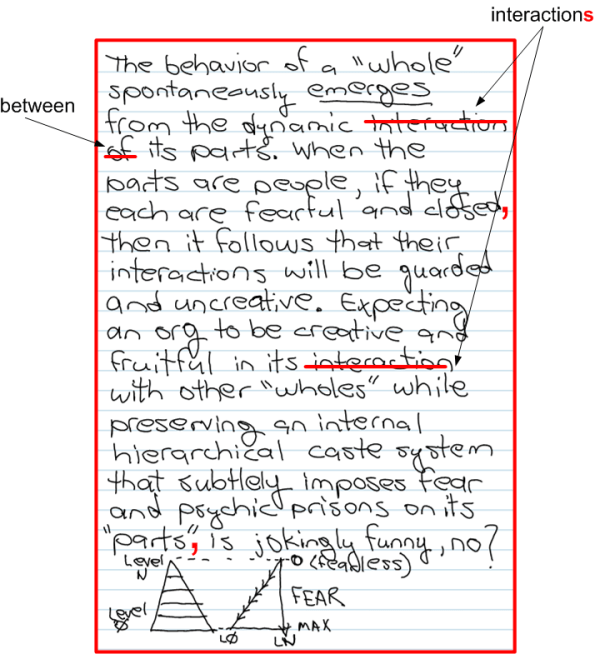

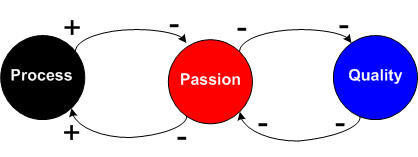

Process, Passion, And Quality

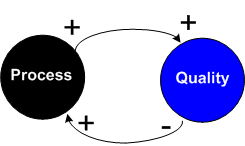

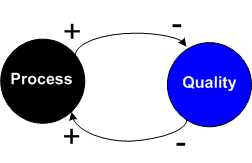

Naive managers (usually those who get drunk on large quantities of 6-sigma, CMMI, ISO-90XX, EVM, and/or PMP kool aid) tend to think of the correlation between process and quality like this:

This cause-effect diagram can be read as “more process imposition leads to more quality; less quality leads to more process imposition“. What’s missing in this simplistic diagram? Could it be something that represents the human element?

This cause-effect diagram can be read as “more process imposition leads to more quality; less quality leads to more process imposition“. What’s missing in this simplistic diagram? Could it be something that represents the human element?

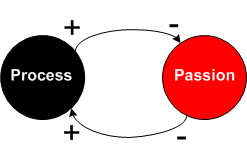

In the blarticle, “Process kills developer passion“, James Turner writes about the human element of “passion“:

…passionate programmers write great code, but process kills passion. Disaffected programmers write poor code, and poor code makes management add more process in an attempt to “make” their programmers write good code. That just makes morale worse, and so on.

If you believe Mr. Turner, then the cause-effect diagram for process and passion is a self-reinforcing loop that may snuff out passion over time:

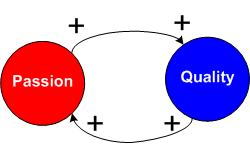

So, what about the relationship between passion and quality? I think that many would agree that it is thus:

So, what about the relationship between passion and quality? I think that many would agree that it is thus:

When we integrate the two models above, we get….

When we integrate the two models above, we get….

Moving from left to right, and then from right to left we read that:

Moving from left to right, and then from right to left we read that:

an increase in process triggers a decrease in passion, which triggers a decrease in quality, which triggers a further decrease in passion, which triggers an increase in process imposition. Round and round we go.

If we assume that “passion” is an integral player in the system, but hide it in the above diagram to simulate a common managerial blindspot, the end to end process-quality cause-effect diagram emerges as:

If we compare this derived result to the first naive manager mental model which doesn’t include the messy “passion” element, what’s the difference?

If we compare this derived result to the first naive manager mental model which doesn’t include the messy “passion” element, what’s the difference?

What’s On Your List?

In Russell Ackoff‘s “Idealized Design” method, he suggests that designers assume that the system they’re trying to improve/re-design exploded last night and it no longer exists. D’oh! He does this in order to put a jackhammer to the layers of unquestioned, un-noticed, outdated, and hard-wired assumptions that reside in every designer’s mind.

So, if you were part of an emergency task force charged with re-designing your no-longer-existing org, what candidate list of ideas would you concoct? To help jumpstart your underused, but innately powerful creative talents, here’s an outrageous example list that I stole from a raging lunatic:

- Provide two computer monitors for every employee and religiously refresh workstations every three years.

- Provide two projectors and multiple whiteboards in each conference room. Ensure a plentiful supply of working markers. No exclusive executive conference rooms – all rooms equally accessible to all, with negotiated overrides.

- Physically co-locate all product and project teams for the duration. Disallow a rotating door where projectees can come and go as they please or management pleases – with rare exceptions of course.

- Put round tables in every conference room.

- Distribute executive and middle manager offices throughout the org. No bunching in a cloistered, elitist corner, space, or glistening building with HR/Marketing/PR/finance/contracts or other overhead functions.

- Require every manager in the org with direct reports to periodically ask each direct report: “How can I help you do your job better?” at frequent one-on-one meetings. If a manager has too many direct reports – then fix it somehow.

- Require every manager who has managers reporting to him/her to ask each of his/her subordinate managers: “Can you give me an example of how you helped one or more of your direct reports to grow and develop this year?“.

- Require periodic, skip-level manager-subordinate meetings where the manager triggers the conversation and then just listens.

- If “schedule is king” all the time, then write it into your prioritized core values list – just above “engineering excellence and elegant products“. If your core values list contains conflicting values, then prioritize it.

- Carefully and continuously monitor group (not individual) interaction protocols and behaviors. Diligently prevent protocol bloat and convert tightly coupled, synchronous client-server relationships into loosely couple, asynchronous, peer-to-peer exchanges.

- Explicitly budget X days of user-chosen training to every person in the org and enforce the policy’s execution.

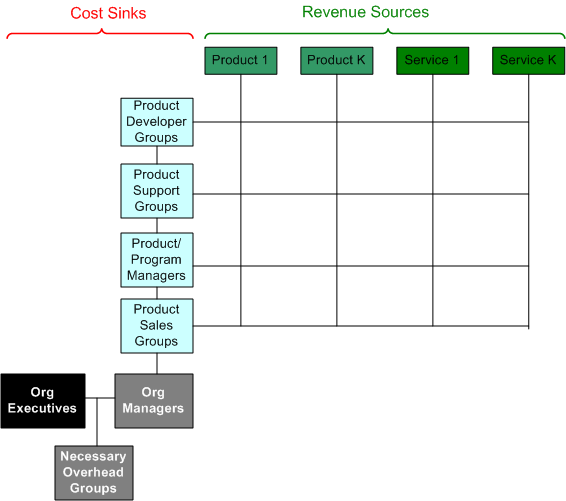

- To reinforce why the org exists and de-emphasize who is “more important” than who, publish a product and/or service-centric org chart with products/services across the top and groups, including all managers, down the side. Preferably, the managers should be on the bottom propping up the org. (See figure below).

- Abandon the “employee-in-a-box” classification and reward system. Pay each person enough so that pay isn’t an issue, and publicly publish all salaries as a self-regulating mechanism.

- Create policy making and problem solving councils up and down the org. Members must consist of three levels of titles and include both affectees in addition to effectors.

- Give leadees a say regarding who their leaders are. Publicly publish all reviews of leaders by leadees.

- Require periodic job rotations to reduce the org’s truck number.

- Frequently survey the entire org for ideas and problem hot spots. Visibly act on at least concern within a relatively short amount of time after each survey.

- Provide every employee with an org credit card and budget a fixed amount of money where no approvals are required for purchases. Fix the purchasing system to make it ridiculously easy for expenses to be submitted.

Synthanalysis

According to Russell Ackoff, there are two thinking tools for developing an understanding of how existing socio-technical systems work: analysis (reductionism) and synthesis (constructionism). Since analysis is taught in school (and synthesis is not – except in the arts), analysis is a well known tool to problem solvers. Synthesis is not taught in schools because it’s hard to teach – it’s a less methodical and more metaphysical technique than analysis.

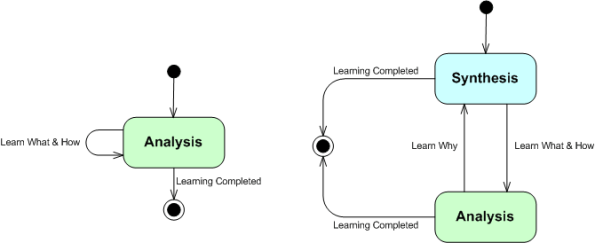

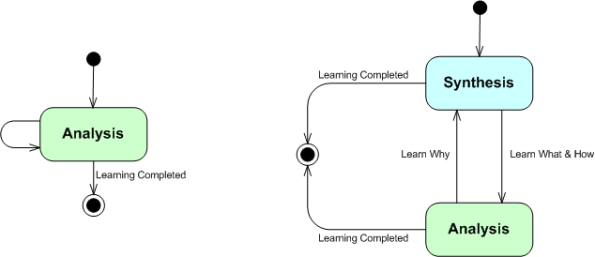

The UML state machine diagram below models the behavior of two different problem solvers – one that exclusively uses analysis and one that bounces non-deterministically between analysis and synthesis. Note that the purpose of entering and dwelling in the synthesis state is to learn the holistic “why” of a system – which always lies outside of the system.

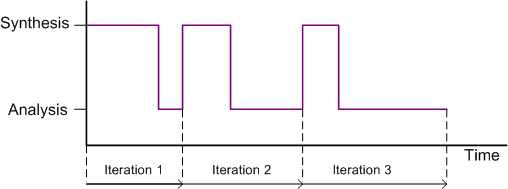

The figure below shows a typical example trace of a synthanalyst problem solver’s behavior over time. Over each iteration toward a viable solution to the problem at hand, a synthanalyst dwells less and less in the synthesis state and more and more in the analysis state. The behavior trace for a one dimensional analyzer is not shown because it’s trivial. It’s a boring and unadventurous flat line – one that self-smug managers trace out every day at work.

SOI Sauce

Assume that you’re given a bounded “System Of Interest” (SOI) you desperately want to understand. Cuz it’s a ‘nuther whole can of worms, please suspend “reality” for a moment and fuggedaboud who defined the SOI boundaries and plopped it onto your lap to study.

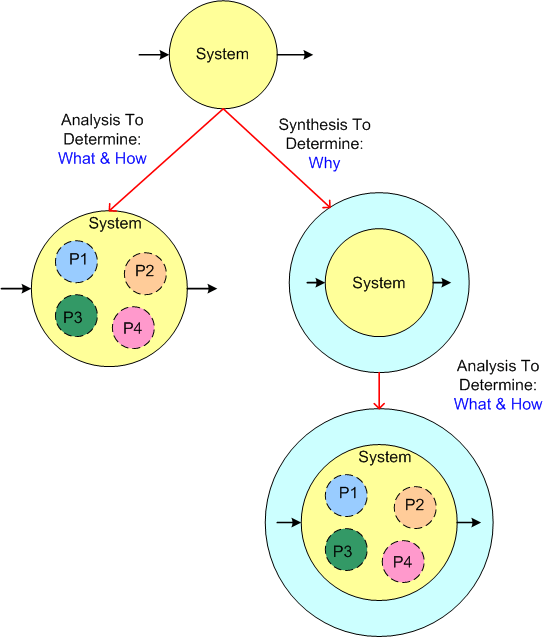

So, where and how do you start attacking the task at hand? Being a member of a western, logical, science-revering culture, you’ll most likely take the analysis path as depicted in the left side of the figure below. You’d try to discern what the SOI’s elemental parts are (forming your own arbitrary part-boundaries, of course) and how each of the parts behaves independently of the others. After performing due diligence at the parts level, you’d aggregate the fragmented part-behaviors together into one grand theory of operation and voila….. you’re done! Because the reductionist approach doesn’t explore the why of the SOI, you’d most likely be wrong. If one or more of the system “parts” is self-purposeful, uh, like people, you’d most likely be 100% wrong.

A complementary approach to understanding a SOI concerns formulating the why of the system – first. As the right-side path in the above figure conveys, the synthesis approach to understanding starts with the exploration of the super-system that contains the SOI. Upon gaining an understanding of the operational context of the SOI within its parent system (the why), the what and the how of the SOI’s parts can be determined with greater accuracy and insight.

The figure below illustrates side-by-side state machine models of the two approaches toward system understanding. Which one best represents the way you operate?

Undetected Course Change

Every organized system of interdependent parts has a primary purpose – otherwise the conglomeration wouldn’t be a “system“. Assume that at T=0, a hypothetical system whose parts are an assemblage of people and machines is placed into operation. As the figure below shows, the system will start moving toward the achievement of its purpose.

Over time, assume that our fictitious system “loses its way” because of ineffective control actions. In hierarchically structured systems, the likelihood that the internal system controllers will detect the derailment and steer the system back on course is pitifully small. That’s because hierachical forms of human organization tend to instill a false sense of infallibility and hubris in those who control the system’s trajectory. Thus, via the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance and the inability to admit mistakes, the controllers will continue to shepherd the system away from its primary purpose toward a different, and most likely less noble purpose – all the while espousing that “we are on course to achieve our objectives“.

Idioticon

When I first saw the word “idioticon“, I thought it was a concatenation of the two words “idiot” and “icon“. You know, something like this:

Here’s what it really means:

The fine folks at Triarchy Press have started writing an online idioticon of systems thinking ideas. The first two fascinating entries are titled “The Edge of Chaos” and “The Accursed Share“. Go check them out.