Archive

Ackoff On Systems Thinking

Russell Ackoff, bless his soul, was a rare, top echelon systems thinker who successfully avoided being assimilated by the borg. Checkout the master’s intro to systems thinking in the short series of videos below.

What do you think?

Leverage Point

In this terrific systems article pointed out to me by Byron Davies, Donella Meadows states:

Physical structure is crucial in a system, but the leverage point is in proper design in the first place. After the structure is built, the leverage is in understanding its limitations and bottlenecks and refraining from fluctuations or expansions that strain its capacity.

The first sentence doesn’t tell me anything new, but the second one does. Many systems, especially big software systems foisted upon maintenance teams after they’re hatched to the customer, are not thoroughly understood by many, if any, of the original members of the development team. Upon release, the system “works” (and it may be stable). Hurray!

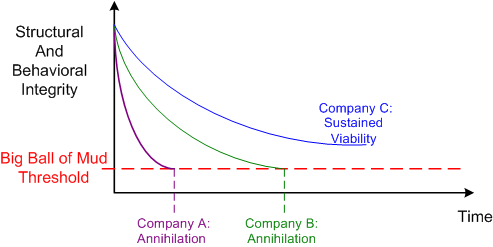

In the post delivery phase, as the (always) unheralded maintenance team starts adding new features without understanding the system’s limitations and bottlenecks, the structural and behavioral integrity of the beast starts surely degrading over time. Scarily, the rate of degradation is not constant; it’s more akin to an exponential trajectory. It doesn’t matter how pristine the original design is, it will undoubtedly start it’s march toward becoming an unlovable “big ball of mud“.

So, how can one slow the rate of degradation in the integrity of a big system that will continuously be modified throughout its future lifetime? The answer is nothing profound and doesn’t require highly skilled specialists or consultants. It’s called PAYGO.

In the PAYGO process, a set of lightweight but understandable and useful multi-level information artifacts that record the essence of the system are developed and co-evolved with the system software. They must be lightweight so that they are easily constructable, navigable, and accessible. They must be useful or post-delivery builders won’t employ them as guidance and they’ll plow ahead without understanding the global ramifications of their local changes. They must be multi-level so that different stakeholder group types, not just builders, can understand them. They must be co-evolved so that they stay in synch with the real system and they don’t devolve into an incorrect and useless heap of misguidance. Challenging, no?

Of course, if builders, and especially front line managers, don’t know how to, or don’t care to, follow a PAYGO-like process, then they deserve what they get. D’oh!

Continuous Husbandry

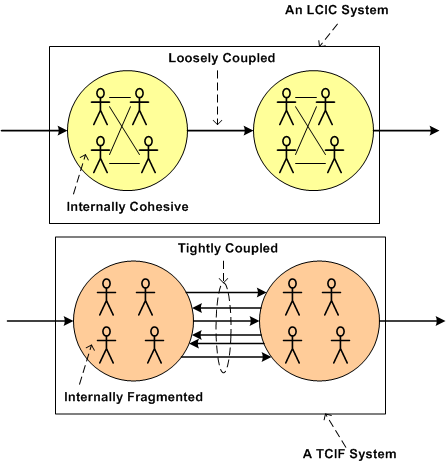

One definition of a system is “a collection of interacting elements designed to fulfill a purpose“. A well known rule of thumb for designing robust and efficient social, technical, and socio-technical systems is:

Keep your system elements Loosely Coupled and Internally Cohesive (LCIC)

The opposite of this golden rule is to design a system that has Tightly Coupled and Internally Fragmented (TCIF) elements. TCIF systems are rigid, inflexible, and tough to troubleshoot when the system malfunctions.

Designing, building, testing, and deploying LCIC systems is not enough to ensure that the system’s purpose will be fulfilled over long periods of time. Because of the relentless increase in entropy dictated by the second law of thermodynamics, continuous husbandry (as my friend W. L. Livingston often says) is required to arrest the growth in entropy. Without husbandry, LCIC systems (like startup companies) morph into TCIF systems (like corpocracies). The transformation can be so slooow that it is undetectable – until it’s too late. In subtle LCIC-to-TCIF transformations, it takes a crisis to shake the system architect(s) into reality. In a sudden jolt of awareness, they realize that their cute and lovable baby has turned into an uncontrollable ogre capable of massive stakeholder destruction. Bummer.

Background Daemons

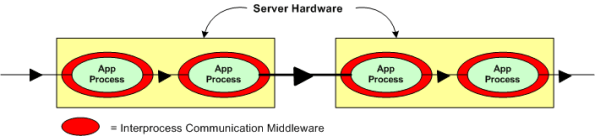

Assume that you have to build a distributed real-time system where your continuously communicating application components must run 24×7 on multiple processor nodes netted together over a local area network. In order to save development time and shield your programmers from the arcane coding details of setting up and monitoring many inter-component communication channels, you decide to investigate pre-written communication packages for inclusion into your product. After all, why would you want your programmers wasting company dollars developing non-application layer software that experts with decades of battle-hardened experience have already created?

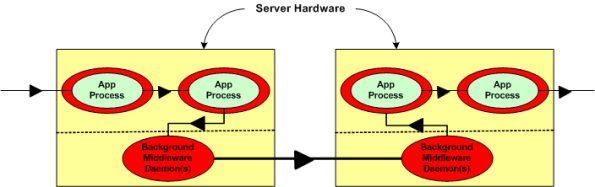

Now, assume that the figure below represents a two node portion of your many-node product where a distributed architecture middleware package has been linked (statically or dynamically) into each of your application components. By distributed architecture, I mean that the middleware doesn’t require any single point-of-failure daemons running in the background on each node.

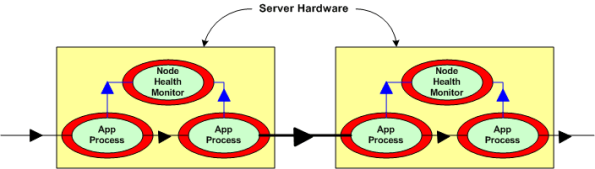

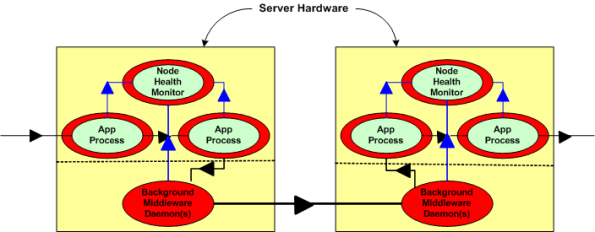

Next, assume that to increase reliability, your system design requires an application layer health monitor component running on each node as in the figure below. Since there are no daemons in the middleware architecture that can crash a node even when all the application components on that node are running flawlessly, the overall system architecture is more reliable than a daemon-based one; dontcha think? In both distributed and daemon-based architectures, a single application process crash may or may not bring down the system; the effect of failure is application-specific and not related to the middleware architecture.

The two figures below represent a daemon-based alternative to the truly distributed design previously discussed. Note the added latency in the communication path between nodes introduced by the required insertion of two daemons between the application layer communication endpoints. Also note in the second figure that each “Node Health Monitor” now has to include “daemon aware” functionality that monitors daemon state in addition to the co-resident application components. All other things being equal (which they rarely are), which architecture would you choose for a system with high availability and low latency requirements? Can you see any benefits of choosing the daemon-based middleware package over a truly distributed alternative?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that is not there – because it isn’t needed.

iSpeed OPOS

A couple of years ago, I designed a “big” system development process blandly called MPDP2 = Modified Product Development Process version 2. It’s version 2 because I screwed up version 1 badly. Privately, I named it iSpeed to signify both quality (the Apple-esque “i”) and speed but didn’t promote it as such because it didn’t sound nerdy enough. Plus, I was too chicken to introduce the moniker into a conservative engineering culture that innocently but surely suppresses individuality.

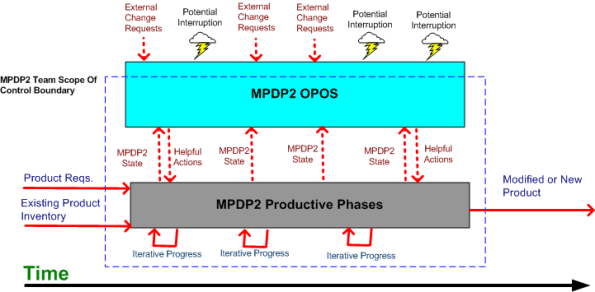

One of the MPDP2 activties, which stretches across and runs in parallel to the time sequenced development phases, is called OPOS = Ongoing Planning, Ongoing Steering. The figure below shows the OPOS activity gaz-intaz and gaz-outaz.

In the iSpeed process, the top priority of the project leader (no self-serving BMs allowed) is to buffer and shield the engineering team from external demands and distractions. Other lower priority OPOS tasks are to periodically “sample the value stream”, assess the project state, steer progress, and provide helpful actions to the multi-disciplined product development team. What do you think? Good, bad, fugly? Missing something?

The Rise Of The “ilities”

The title of this post should have been “The Rise Of Non-Functional Requirements“, but that sounds so much more gauche than the chosen title.

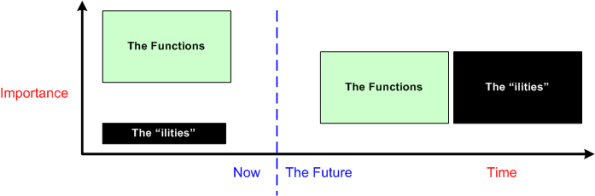

As software-centric systems get larger and necessarily more complex, they take commensurately more time to develop and build. Making poor up front architectural decisions on how to satisfy the cross-cutting non-functional requirements (scalability, distribute-ability, response-ability (latency), availability, usability, maintainability, evolvability, portability, secure-ability, etc.) imposed on the system is way more costly downstream than making bad up front decisions regarding localized, domain-specific functionality. To exacerbate the problem, the unglamorous “ilities” have been traditionally neglected and they’re typically hard to quantify and measure until the system is almost completely built. Adding fuel to the fire, many of the “ilities” conflict with each other (e.g. latency vs maintainability, usability vs. security). Optimizing one often marginalizes one or more others.

When a failure to meet one or more non-functional requirements is discovered, correcting the mistake(s) can, at best, consume a lot of time and money, and at worst, cause the project to crash and burn (the money’s gone, the time’s gone, and the damn thang don’t work). That’s because the mechanisms and structures used to meet the “ilities” requirements cut globally across the entire system and they’re pervasively weaved into the fabric of the product.

If you’re a software engineer trying to grow past the coding and design patterns phases of your profession, self-educating yourself on the techniques, methods, and COTS technologies (stay away from homegrown crap – including your own) that effectively tackle the highest priority “ilities” in your product domain and industry should be high on your list of priorities.

Because of the ubiquitous propensity of managers to obsess on short term results and avoid changing their mindsets while simultaneously calling for everyone else to change theirs, it’s highly likely that your employer doesn’t understand and appreciate the far reaching effects of hosing up the “ilities” during the front end design effort (the new age agile crowd doesn’t help very much here either). It’s equally likely that your employer ain’t gonna train you to learn how to confront the growing “ilities” menace.

Incremental Chunked Construction

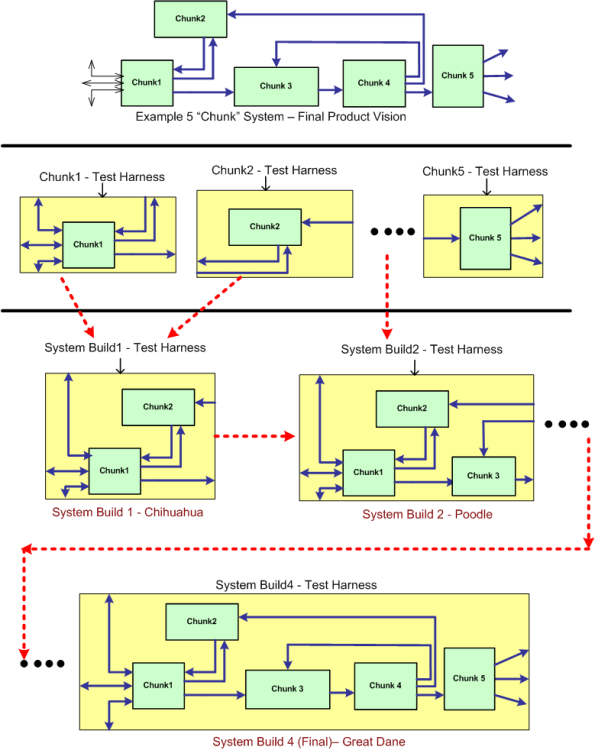

Assume that the green monster at the top of the figure below represents a stratospheric vision of a pipelined, data-centric, software-intensive system that needs to be developed and maintained over a long lifecycle. By data-centric, I mean that all the connectors, both internal and external, represent 24 X 7 real-time flows of streaming data – not “client requests” for data or transactional “services”. If the Herculean development is successful, the product will both solve a customer’s problem and make money for the developer org. Solving a problem and making money at the same time – what a concept, eh?

One disciplined way to build the system is what can be called “incremental chunked construction”. The system entities are called “chunks” to reinforce the thought that their granularity is much larger than a fine grained “unit” – which everybody in the agile, enterprise IT, transaction-centric, software systems world seems to be fixated on these days.

Follow the progression in the non-standard, ad-hoc diagram downward to better understand the process of incremental chunked development. It’s not much different than the classic “unit testing and continuous integration” concept. The real difference is in the size, granularity, complexity and automation-ability of the individual chunk and multi-chunk integration test harnesses that need to be co-developed. Often, these harnesses are as large and complex as the product’s chunks and subsystems themselves. Sadly, mostly due to pressure from STSJ management (most of whom have no software background, mysteriously forget repeated past schedule/cost performance shortfalls, and don’t have to get their hands dirty spending months building the contraption themselves), the effort to develop these test support entities is often underestimated as much as, if not more than, the product code. Bummer.

My OSEE Experience

Intro

A colleague at work recently pointed out the existence of the Eclipse org’s Open System Engineering Environment (OSEE) project to me. Since I love and use the Eclipse IDE regularly for C++ software development, I decided to explore what the project has to offer and what state it is in.

The OSEE is in the “incubation” stage of development, which means that it is not very mature and it may require a lot more work before it has a chance of being accepted by a critical mass of users. On the project’s main page, the following sentences briefly describe what the OSEE is:

The Open System Engineering Environment (OSEE) project provides a tightly integrated environment supporting lean principles across a product’s full life-cycle in the context of an overall systems engineering approach. The system captures project data into a common user-defined data model providing bidirectional traceability, project health reporting, status, and metrics which seamlessly combine to form a coherent, accurate view of a project in real-time.

The feature list is as follows:

- End-to-end traceability

- Variant configuration management

- Integrated workflows and processes

- A Comprehensive issue tracking system

- Deliverable document generation

- Real-time project tracking and reporting

- Validation and verification of mission software

I don’t know about you, but the OSEE sounds more like an integrated project management tool than a system engineering toolset that facilitates requirements development and system design. Promoting the product ambiguously may be intended to draw in both system engineers and program managers?

The OSEE is not a design-by-committee, fragmented quagmire, it’s a derivation of a real system engineering environment employed for many years by Boeing during the development of a military helicopter for the US government. Like IBM was to the Eclipse framework, Boeing is to the OSEE.

“Standardization without experience is abhorrent.” – Bjarne Stroustrup

Download, Install, Use

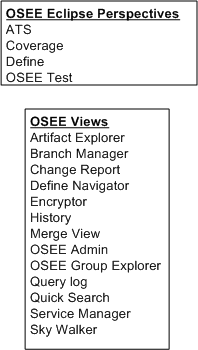

The figure below shows a simple model of the OSEE architecture. The first thing I did was download and install the (19) Eclipse OSEE plugins and I had no problem with that. Next, I tried to install and configure the required PostgresQL database and OSEE application and OSEE arbitration servers. After multiple frustrating tries, and several re-reads of the crappy install documentation, I said WTF! and gave up. I did however, open and explore various OSEE related Eclipse perspectives and views to try and get a better feel for what the product can do.

As shown in the figure below, the OSEE currently renders four user-selectable Eclipse perspectives and thirteen views. Of course, whenever I opened a perspective (or a view within a perspective) I was greeted with all kinds of errors because the OSEE back end kludge was not installed correctly. Thus, I couldn’t create or manipulate any hypothetical “system engineering” artifacts to store in the project database.

Conclusion

As you’ve probably deduced, I didn’t get much out of my experience of trying to play around with the OSEE. Since it’s still in the “incubation” stage of development and it’s free, I shouldn’t be too harsh on it. I may revisit it in the future, but after looking at the OSEE perspective/view names above and speculating about their purposes, I’ve pre-judged the OSEE to be a heavyweight bureaucrat’s dream and not really useful to a team of engineers. Bummer.

Exploring Processor Loading

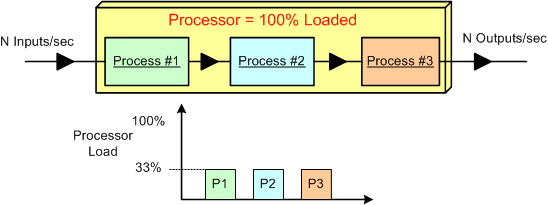

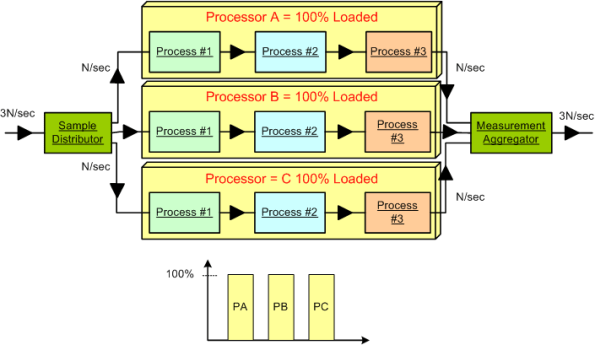

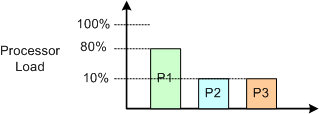

Assume that we have a data-centric, real-time product that: sucks in N raw samples/sec, does some fancy proprietary processing on the input stream, and outputs N value-added measurements/sec. Also assume that for N, the processor is 100% loaded and the load is equally consumed (33.3%) by three interconnected pipeline processes that crunch the data stream.

Next, assume that a new, emerging market demands a system that can handle 3*N input samples per second. The obvious solution is to employ a processor that is 3 times as fast as the legacy processor. Alternatively, (if the nature of the application allows it to be done) the input data stream can be split into thirds , the pipeline can be cloned into three parallel channels allocated to 3 processors, and the output streams can be aggregated together before final output. Both the distributor and the aggregator can be allocated to a fourth system processor or their own processors. The hardware costs would roughly quadruple, the system configuration and control logic would increase in complexity, but the product would theoretically solve the market’s problem and produce a new revenue stream for the org. Instead of four separate processor boxes, a single multi-core (>= 4 CPUs) box may do the trick.

We’re not done yet. Now assume that in the current system, process #1 consumes 80% of the processor load and, because of input sample interdependence, the input stream cannot be split into 3 parallel streams. D’oh! What do we do now?

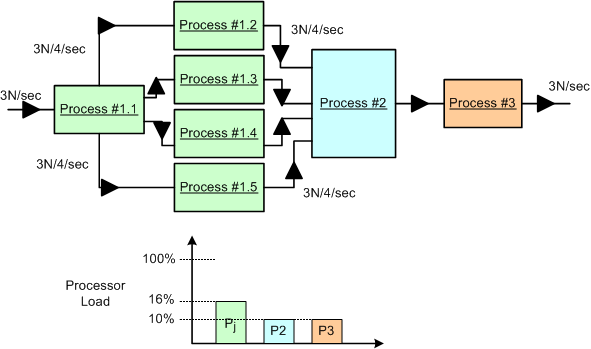

One approach is to dive into the algorithmic details of the P1 CPU hog and explore parallelization options for the beast. Assume that we are lucky and we discover that we are able to divide and conquer the P1 oinker into 5 equi-hungry sub-algorithms as shown below. In this case, assuming that we can allocate each process to its own CPU (multi-core or separate boxes), then we may be done solving the problem at the application layer. No?

Do you detect any major conceptual holes in this blarticle?

Machine Age Thinking, Systems Age Thinking

In Ackoff’s Best, Mr. Russell Ackoff states the following

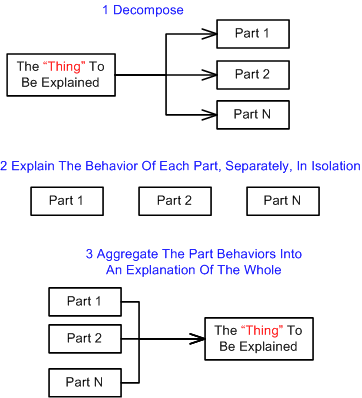

…Machine-Age thinking: (1) decomposition of that which is to be explained, (2) explanation of the behavior or properties of the parts taken separately, and (3) aggregating these explanations into an explanation of the whole. This third step, of course, is synthesis.

The figure below models the classical machine age, mechanistic thinking process described by Ackoff. The problem with this antiquated method of yesteryear is that it doesn’t work very well for systems of any appreciable complexity – especially large socio-technical systems (every one of which is mind-boggingly complex). During the decomposition phase, the interactions between the parts that animate the “thing to be explained” are lost in the freakin’ ether. Even more importantly, the external environment in which the “thing to be explained” lives and interacts is nowhere to be found. This is a huge mistake because the containing environment always has a profound effect on the behavior of the system as a whole.

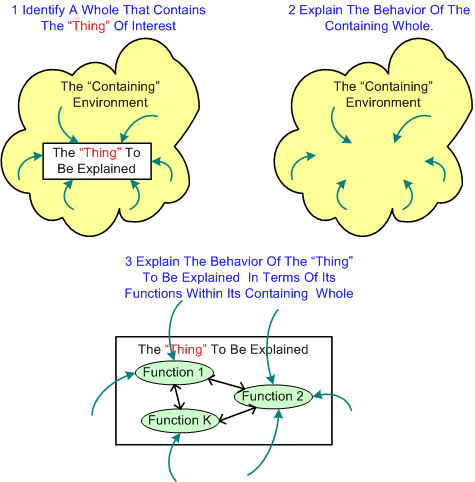

Mr. Ackoff professes that the antidote to mechanistic thinking is……. system thinking (duh!):

In the systems approach there are also three steps:

1. Identify a containing whole (system) of which the thing to be explained is a part.

2. Explain the behavior or properties of the containing whole.

3. Then explain the behavior or properties of the thing to be explained in terms of its role(s) or function(s) within its containing whole.

Note that in this sequence, synthesis precedes analysis.

The figure below graphically depicts the systems thinking process. Note that the relationships between the “thing to be explained” and its containing whole are first class citizens in this mode of thinking.

One of the primary reasons why we seek to understand systems is so that we can diagnose and solve problems that arise within established systems; or to design new systems to solve problems that need to be controlled or ameliorated. By applying the wrong thinking style to a system problem, the cure often ends up being worse than the disease. D’oh!

One of the primary reasons why we seek to understand systems is so that we can diagnose and solve problems that arise within established systems; or to design new systems to solve problems that need to be controlled or ameliorated. By applying the wrong thinking style to a system problem, the cure often ends up being worse than the disease. D’oh!