Archive

Proximity In Space And Time

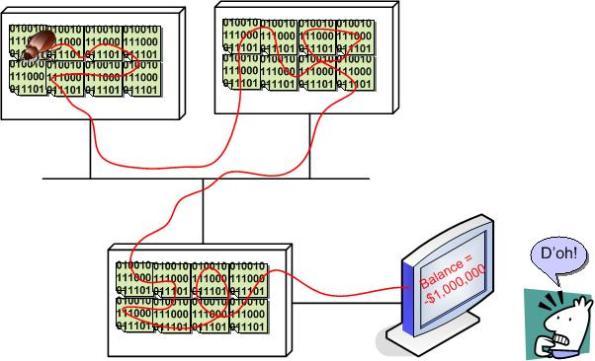

When a failure occurs in a complex, networked, socio-technical system, the probability is high that the root cause is located far away from the failure detection point in time, space, or both. The progression in time goes something like this:

fault ———–> error———-> error—————–>error——>failure discovered!

An unanticipated fault begets an error, which begets another error(s), which begets another error(s), etc, until the failure is manifest via loss of life or money somewhere and sometime downstream in the system. In the case of a software system, the time from fault to catastrophic failure may take milliseconds, but the distance between fault and failure can be in the 100s of thousands of lines of source code sprinkled across multiple machines and networks.

Let’s face it. Envisioning, designing, coding, and testing for end-to-end “system level” error conditions in software systems is unglamorous and tedious (unless you’re using Erlang – which is thoughtfully designed to lessen the pain). It’s usually one of the first things to get jettisoned when the pressure is ratcheted up to meet some arbitrary schedule premised on a baseless, one-time, estimate elicited under duress when the project was kicked-off. Bummer.

Heaven And Hell

This is one of those picture-only posts where BD00 invites you to fill in the words of the missing story…

Code First And Discover Later

In my travels through the whacky world of software development, I’ve found that bottom up design (a.k.a code first and “discover” the real design later) can lead to lots of unessential complexity getting baked into the code. Once this unessential complexity, in the form of extraneous classes and a rats nest of unneeded dependencies, gets baked into the system and the contraption “appears to work” in a narrow range of scenarios, the baker(s) will tend to irrationally defend the “emergent” design to the death. After all, the alternative would be to suffer humility and perform lots of risky, embarrassing, and ego-busting disentanglement rework. Of course, all of these behaviors and processes are socially unacceptable inside of orgs with macho cultures; where publicly admitting you’re wrong is a career-ending move. And that, my dear, is how we have created all those lovable, “legacy” systems that run the world today.

Don’t get BD00 wrong here. The esteemed one thinks that bottom up design and coding is fine for small scoped systems with around 7 +/- 2 classes (Miller’s number), but this “easy and fun and fast” approach sure doesn’t scale well. Even more ominously, the bottom up coding and emergent design strategy is unacceptable for long-lived, safety-critical systems that will be scrutinized “later on” by external technical inspectors.

Four Possible Paths, Eight Possible Outcomes

The graphic below transforms the title of this post into a visual manifestation that can be discussed “rationally” (<— LOL!).

The graphic shows that pursuing any of the four path selections can lead to a “number 2” outcome. It’s just a matter of how much time and money are exhausted before the steaming pile is discovered. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Obviously, the path to the holy grail is D->1. Simply take whatever info is known about the problem, code up the solution, get paid tons o’ munny, move on to the next problem to be solved, and never look back. Whoo Hoo! I love when that happens.

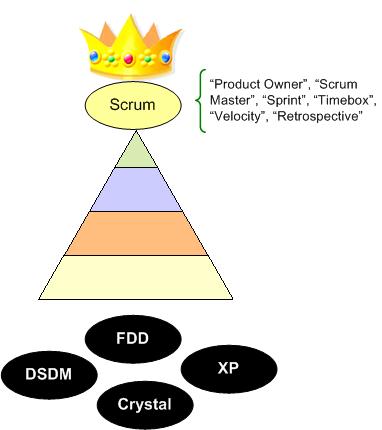

King Of The Hill

Scrum is an agile approach to software development, but it’s not the only agile approach. However, because of its runaway success of adoption compared to other agile approaches (e.g. XP, DSDM, Crystal, FDD), a lot of the pro and con material I read online seems to assume that Agile IS Scrum.

This nitpicking aside, until recently, I wondered why Scrum catapulted to the top of the agile heap over the other worthy agile candidates. Somewhere online, someone answered the question with something like:

“Scrum is king of the hill right now because it’s closer to being a management process than a geeky, code-centric set of practices. Thus, since enlightened executives can pseudo-understand it, they’re more likely to approve of its use over traditional prescriptive processes that only provide an illusion of control and a false sense of security.”

I think that whoever said that is correct. Why do you think Scrum is currently the king of the hill?

Related articles

- The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (bulldozer00.com)

- Scrum And Non-Scrum Interfaces (bulldozer00.com)

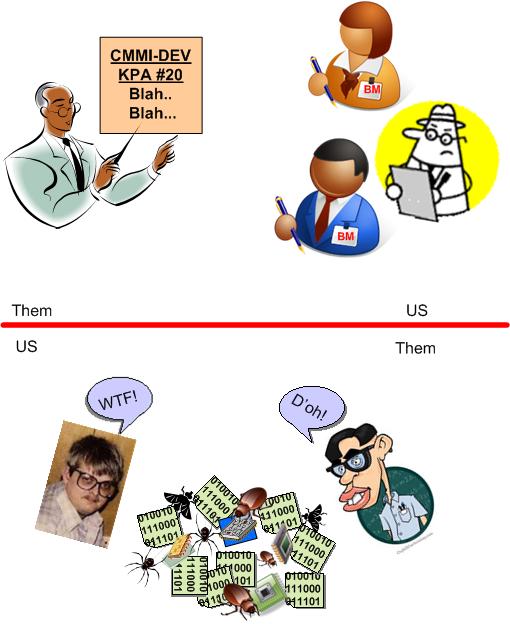

Blown, Busted, And Riddled

The CMMI-DEV model for software development contains 20+ Key Process Areas (KPA) that are required to be addressed by an org in order to achieve a respectable level of compliance. With such complexity, one could think that L3+ orgs would sponsor periodic process refresher courses for their DICforces in order to minimize social friction between process enforcers and enforcees and reduce time-sucking rework resulting from innocent process execution errors made by the enforcees.

BD00 postulates that many CMMI L3+ orgs don’t hold periodic, rolling process refreshers for their cellar dwellers. The worst of the herd periodically retrains its technical management and process groups (enforcers) , but not its product development teams (enforcees). These (either clueless or innocently ignorant) orgs deserve what they get. Not only do they get blown budgets, busted schedules, and bug-riddled products, but they ratchet up the “us vs. them” social friction between the uninformed hands-on product dweebs and the informed PWCE elites.

A Stone Cold Money Loser

A widespread and unquestioned assumption deeply entrenched within the software industry is:

For large, long-lived, computationally-dense, high-performance systems, this attitude is a stone cold money loser. When the original cast of players has been long departed, and with hundreds of thousands (perhaps millions) of lines of code to scour, how cost-effective and time-effective do you think it is to hurl a bunch of overpaid programmers and domain analysts at a logical or numerical bug nestled deeply within your golden goose. What about an infrastructure latency bug? A throughput bug? A fault-intolerance bug? A timing bug?

Everybody knows the answer, but no one, from the penthouse down to the boiler room wants to do anything about it:

To lessen the pain, note that to be “kind” (shhh! Don’t tell anyone) BD00 used the less offensive “artifacts” word – not the hated “D” word. And no, I don’t mean huge piles of detailed, out-of-synch, paper that would torch your state if ignited. And no, I don’t mean sophisticated-looking, semantic-less garbage spit out by domain-agnostic tools “after” the code is written.

Wah, wah, wah:

- “But it’s impossible to keep the artifacts in synch with the code” – No, it’s not.

- “But no one reads artifacts” – Then make the artifacts readable.

- “But no one knows how to write good artifacts” – Then teach them.

- “But no one wants to write artifacts” – So, what’s your point? This is a business, not a vacation resort.

Under Or Over?

In general, humans suck at estimating. In specific, (without historical data,) software engineers suck at estimating both the size and effort to build a product – a double whammy. Thus, the bard is wrong. The real thought worth pondering is:

To underestimate or overestimate, that is the question.

In “Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art“, Steve McConnell boldly answers the question with this graph:

As you can see, the fiscal penalty for underestimation rockets out of control much quicker than the penalty for overestimation. In summary, once a project gets into “late” status, project teams engage in numerous activities that they don’t need to engage in if they overestimated the effort: more status meetings with execs, apologies, triaging of requirements, fixing bugs from quick-dirty workarounds implemented under schedule duress, postponing demos, pulling out of trade shows, more casual overtime, etc.

So, now that the under/over question has been settled, what question should follow? How about this scintillating selection:

Why do so many orgs shoot themselves in the foot by perpetuating a culture where underestimation is the norm and disappointing schedule/cost performance reigns supreme?

Of course, BD00 has an answer for it (cuz he’s got an answer for everything):

Via the x-ray power of POSIWID, it’s simply what hierarchical command and control social orgs do; and you can’t ask such an org to be what it ain’t.

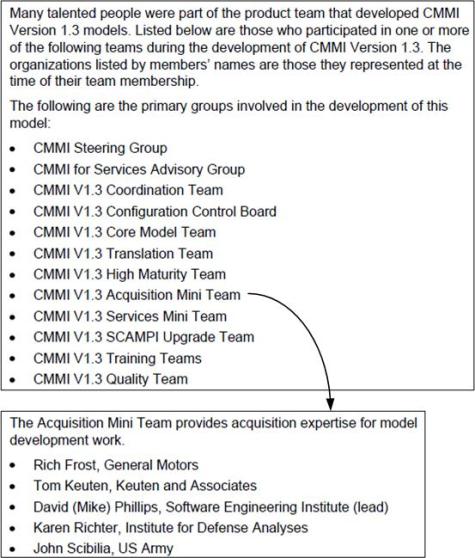

The Org Is The Product

Someone once said something like: “the products an organization produces mirror the type of organization that produces them“. Thus, a highly formal, heavyweight, bureaucratic, title-obsessed, siloed, and rigid org will most likely produce products of the same ilk.

With this in mind, let’s look at the US DoD funded Software Engineering Institute (SEI) and one of its flagship products: the “CMMI® for Development, Version 1.3“. The snippet below was plucked right out of the 482 page technical report that defines the CMMI-DEV:

So, given no other organizational information other than that provided above, what kind of product would you speculate the CMMI-DEV is? Of course, like BD00 always is, you’d be dead wrong if you concluded that the CMMI-DEV is a highly formal, heavyweight, bureaucratic, title-obsessed, siloed, and rigid model for product development.

Firefighter Fran

Being anointed as a firefighter in an org that’s constantly battling blazes is one of the highest callings there is for any group member not occupying a coveted slot in the chief’s inner circle. Hell, since you didn’t start the fire and you’re gonna try your best to save the lot from a financial disaster, it’s a can’t-lose situation. If you fail, you’ll be patted on the back with a “nice try soldier; now we’re gonna go find the firestarter and kick his arse to kingdom come”. If you extinguish the blaze, at least you’ll lock in that 2% raise for this fiscal year. You might even get an accompanying $25 Dunkin Donuts gift card to keep your spare tire inflated with dozens of delectable, confectionary delights.

Given the above context, let’s start this heart-warming story off with you in the glorious role of firefighter Fran. You, my dear Fanny, oops, I mean Franny, have been assigned to put out a major blaze in one of your flagship legacy software products before it spreads to one of the nearby money silos and blows it sky high. Time, as always, is of the utmost importance. D’oh!

Since the burning pile of poop’s “agile” architecture and design documentation is a bunch of fluffy camouflage created solely to satisfy some process compliance checklist, you check out the code base and directly fire up vi (IDEs are for new age pussies!) for some serious sleuthing.

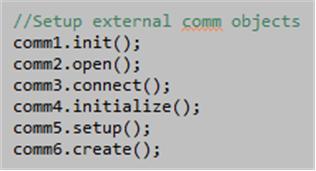

After glancing at the source tree‘s folder structure and concluding that it’s an incomprehensible, acronym-laden quagmire, you take the random plunge. With fingers a tremblin’ and fire hose a danglin’, you open up one of the 5000 source code files that’s postfixed with the word “Main“. You then start sequentially reading some hieroglyphics that’s supposed to be source code and you come to an abrupt halt when you see this:

And… that’s it! The story pauses here because BD00’s lizard brain is about to explode and it’s your turn to provide some “collaborative“, creative input.

So, what does our guaranteed-to-be-hero, fireman Fran, do next? Does the fire get doused? Does the pecuniary silo explode? Is the firestarter ever found? Does Fanny get the DD gift card? If so, how many crullers and donut holes does he scarf down?

Who knows, maybe you can become a self-proclaimed l’artiste like BD00 too, no?