Archive

What’s The Diff?

One of the problems I’ve always had with the word “agile” is that it’s so overloaded (like “system“) that anyone can claim “agility“:

Everyone is doing agile these days – even those who aren’t – Scott Ambler

Along this vein, check out this slide from a unnamed agile expert:

Now tell me, how is this advice different from the unconscionable and anti-agile:

To define tests, you have to have some understanding of the requirements to test against in your cranium, no? It’s just that, in agile-land, you’ll be excommunicated from the cult if you formally write them down before slinging code. WTF?

Like “agile” was a backlash against “waterfall” in the past, maybe “waterfall” will be a circular backlash against “agile” in the future?

Likewise, instead of creating an emergent Frankensteinian design with revered “TDD“, why not hop off the bandwagon and create emergent tests with “DDT“?

Asynchronous Flows And Synchronous Transactions

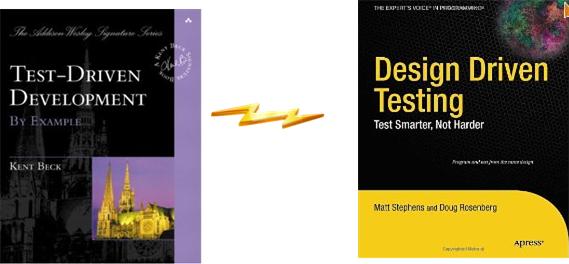

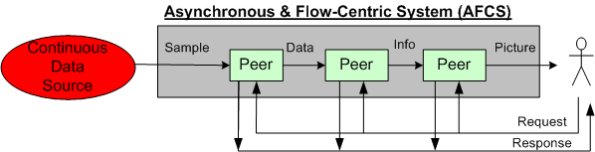

The figure below shows a pair of BD00 concocted models for two classes of systems; peer-to-peer and client-server:

The primary mission of an AFCS is to progressively transform a high rate stream of incoming raw samples into a higher level, abstract representation of some phenomena that’s important to its users. In an STCS, the system’s primary mission is to transform low rate user requests into information that’s important to its users.

In business support applications, STC systems dominate the scene. In aerospace and defense applications, AFC systems are king. Of course, the situation is never as simplistic as BD00 sez. Hybrid systems like the sensor-based command and control model below can be found everywhere.

For some reason (maybe market size and/or community culture and/or media exposure?), most software technology advancements (languages, patterns, methodologies, frameworks, etc) seem to emerge out of the STCS space. Those innovations that are “applicable” get adopted in the AFCS space. Hell, even those that are inapplicable (because they weren’t designed with performance as the top priority) get adopted.

Boulders And Pebbles

When embarking on a Software Product Line (SPL) development, one of the first, far-reaching cost decisions to be tackled is the level of “granularity” of the component set. Obviously, you don’t want to develop one big, fat-ass, 5 million line monstrosity that has to have 1000s of lines changed/added/hacked for each customer “instantiation“. Gee, that’s probably how you operate now and why you’re tinkering with the idea of an SPL approach for the future.

On the other hand, you don’t want to build 1000s of 10K-line pieces that are a nightmare for composition, configuration, versioning and integration. For a given domain, there’s a “subjective” sweet spot somewhere between a behemoth 5M-line boulder and a basket of 10K-line pebbles. However, if you’re gonna err on one side or the other, err on the side of “bigger“:

…beware of overly fine-grained components, because too many components are hard to manage, especially when versioning rears its ugly head, hence “DLL hell.” – Martin Fowler (UML Distilled)

The primacy of system functions and system function groups allows a new member of the product line to be treated as the composition of a few dozen high-quality, high-confidence components that interact with each other in controlled, predictable ways as opposed to thousands of small units that must be regression tested with each new change. Assembly of large components without the need to retest at the lowest level of granularity for each new system is a critical key to making reuse work. – Brownsword/Clements (A Case Study In Successful Product Line Development)

Time For A Toga Party!

Three Degrees Of Distribution

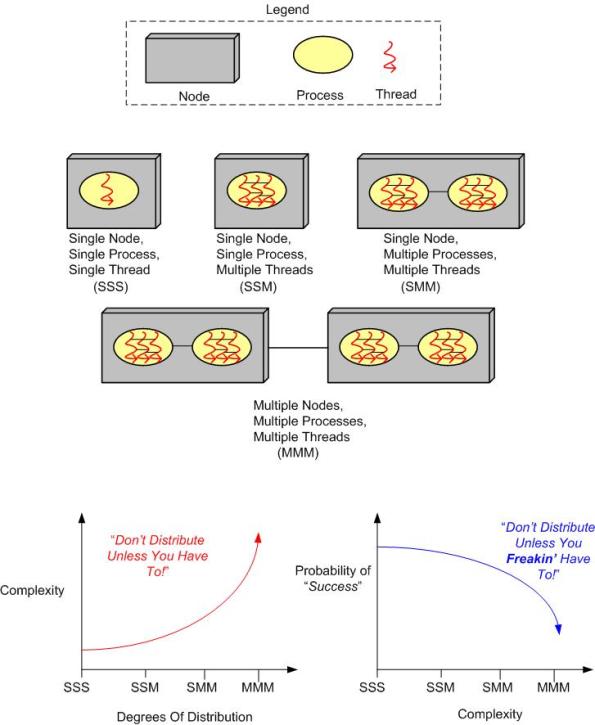

Behold the un-credentialed and un-esteemed BD00’s taxonomy of software-intensive system complexity:

How many “M”s does the system you’re working on have? If the answer is three, should it really be two? If the answer is two, should it really be one? How do you know what number of “M”s your system design should have? When tacking on another “M” to your system design because you “have to“, what newly emergent property is the largest complexity magnifier?

Now, replace the inorganic legend at the top of the page with the following organic one and contemplate how the complexity and “success” curves are affected:

Defect Density

ln “Software’s Hidden Clockwork: A General Theory of Software Defects“, Les Hatton presents these two interesting charts:

The thing I find hard to believe is that Les has concluded that there is no obvious significant relationship between defect density and the choice of programming language. But notice that he doesn’t seem to have any data points on his first chart for the relatively newer, less “tricky“, and easier-to-program languages like Java, C#, Ruby, Python, et al.

So, do you think Les might have jumped the gun here by prematurely asserting the virtual independence of defect density on programming language?

Proximity In Space And Time

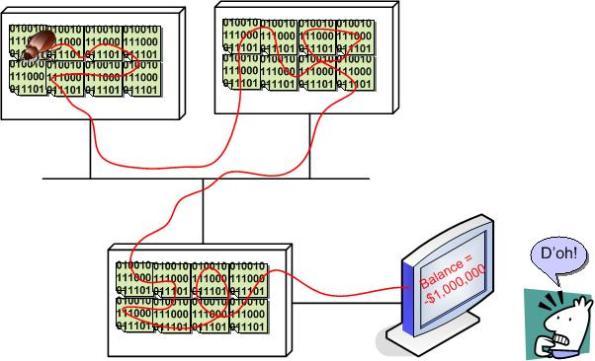

When a failure occurs in a complex, networked, socio-technical system, the probability is high that the root cause is located far away from the failure detection point in time, space, or both. The progression in time goes something like this:

fault ———–> error———-> error—————–>error——>failure discovered!

An unanticipated fault begets an error, which begets another error(s), which begets another error(s), etc, until the failure is manifest via loss of life or money somewhere and sometime downstream in the system. In the case of a software system, the time from fault to catastrophic failure may take milliseconds, but the distance between fault and failure can be in the 100s of thousands of lines of source code sprinkled across multiple machines and networks.

Let’s face it. Envisioning, designing, coding, and testing for end-to-end “system level” error conditions in software systems is unglamorous and tedious (unless you’re using Erlang – which is thoughtfully designed to lessen the pain). It’s usually one of the first things to get jettisoned when the pressure is ratcheted up to meet some arbitrary schedule premised on a baseless, one-time, estimate elicited under duress when the project was kicked-off. Bummer.

Code First And Discover Later

In my travels through the whacky world of software development, I’ve found that bottom up design (a.k.a code first and “discover” the real design later) can lead to lots of unessential complexity getting baked into the code. Once this unessential complexity, in the form of extraneous classes and a rats nest of unneeded dependencies, gets baked into the system and the contraption “appears to work” in a narrow range of scenarios, the baker(s) will tend to irrationally defend the “emergent” design to the death. After all, the alternative would be to suffer humility and perform lots of risky, embarrassing, and ego-busting disentanglement rework. Of course, all of these behaviors and processes are socially unacceptable inside of orgs with macho cultures; where publicly admitting you’re wrong is a career-ending move. And that, my dear, is how we have created all those lovable, “legacy” systems that run the world today.

Don’t get BD00 wrong here. The esteemed one thinks that bottom up design and coding is fine for small scoped systems with around 7 +/- 2 classes (Miller’s number), but this “easy and fun and fast” approach sure doesn’t scale well. Even more ominously, the bottom up coding and emergent design strategy is unacceptable for long-lived, safety-critical systems that will be scrutinized “later on” by external technical inspectors.

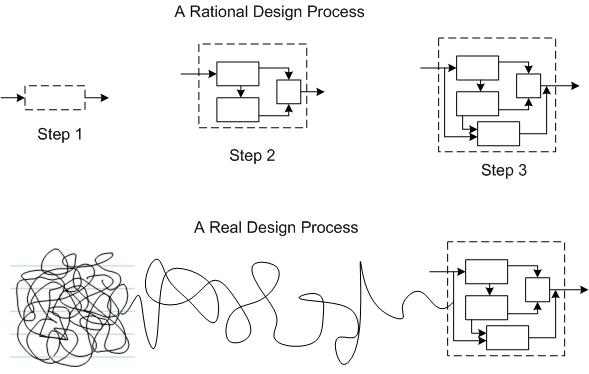

Faking Rationality

I recently dug up and re-read the classic Parnas/Clement 1986 paper: “A Rational Design Process: How And Why To Fake It“. Despite the tendency of people to want to desperately believe the process of design is “rational“, it never is. The authors know there is no such thing as a sequential, rational design process where:

- There’s always a good reason behind each successive design decision.

- Each step taken can be shown to be the best way to get to a well defined goal.

The culprit that will always doom a rational design process is “learning“:

Many of the details only become known to us as we progress in the implementation (of a design). Some of the things that we learn invalidate our design and we must backtrack (multiple times during the process). The resulting design may be one that would not result from a rational design process. – Parnas/Clements

Since “learning“, in the form of going backwards to repair discovered mistakes, is a punishable offense in social command & control hierarchies where everyone is expected to know everything and constantly march forward, the best strategy is to cover up mistakes and fake a rational design process when the time comes to formally present a “finished” design to other stakeholders.

Even though it’s unobtainable, for some strange reason, Spock-like rationality is revered by most orgs. Thus, everyone in org-land plays the “fake-it” game, whether they know it or not. To expect the world to run on rationality is irrational.

Executives preach “evidence-based decision-making“, but in reality they practice “decision-based evidence-making“.

Annoying And Disappointing

Atego’s Artisan Real-Time Studio, Sparx’s Enterprise Architect, and IBM’s Rational Rhapsody are big and expensive UML modeling tools. You would think they support all of the basic visual modeling elements of the UML, no?

On the left side of the figure below, I show the four fundamental, visual UML symbols for conjuring up (wrong, incomplete, and inconsistent) structural views of an object-oriented software system in the form of class diagrams, deployment diagrams, component diagrams, etc.

It blows BD00’s already incoherently twisted mind that Artisan Studio doesn’t provide visual elements for a UML Node or a Component. As can be seen on the right side of the figure, the work-around is to use stereotyped Classifier elements to fill the void. It’s annoying and disappointing, dontcha think?

But hey, not many people (especially extreme left-wing agile zealots) buy into the potential of the UML for shortening the development time and long-term cost of big, sprawling, long-lived software systems . So, “meh” to this irrelevant post.

Note: I’m a relatively newbie user of Artisan Studio. If you’re an advanced user and you know that I’m mistaken here, then please speak up and tell me how to find these two seemingly-hidden buggers.