Archive

A Costly Mistake?

Assume the following:

- Your flagship software-intensive product has had a long and successful 10 year run in the marketplace. The revenue it has generated has fueled your company’s continued growth over that time span.

- In order to expand your market penetration and keep up with new customer demands, you have no choice but to re-architect the hundreds of thousands of lines of source code in your application layer to increase the product’s scalability.

- Since you have to make a large leap anyway, you decide to replace your homegrown, non-portable, non-value adding but essential, middleware layer.

- You’ve diligently tracked your maintenance costs on the legacy system and you know that it currently costs close to $2M per year to maintain (bug fixes, new feature additions) the product.

- Since your old and tired home grown middleware has been through the wringer over the 10 year run, most of your yearly maintenance cost is consumed in the application layer.

The figure below illustrates one “view” of the situation described above.

Now, assume that the picture below models where you want to be in a reasonable amount of time (not too “aggressive”) lest you kludge together a less maintainable beast than the old veteran you have now.

Cost and time-wise, the graph below shows your target date, T1, and your maintenance cost savings bogey, $75K per month. For the example below, if the development of the new product incarnation takes 2 years and $2.25 M, your savings will start accruing at 2.5 years after the “switchover” date T1.

Now comes the fun part of this essay. Assume that:

- Some other product development group in your company is 2 years into the development of a new middleware “candidate” that may or may not satisfy all of your top four prioritized goals (as listed in the second figure up the page).

- This new middleware layer is larger than your current middleware layer and complicated with many new (yet at the same time old) technologies with relatively steep learning curves.

- Even after two years of consumed resources, the middleware is (surprise!) poorly documented.

- Except for a handful of fragmented and scattered powerpoint files, programming and design artifacts are non-existent – showing a lack of empathy for those who would want to consider leveraging the 2 year company investment.

- The development process that the middleware team is using is fairly unstructured and unsupervised – as evidenced by the lack of project and technical documentation.

- Since they’re heavily invested in their baby, the members of the development team tend to get defensive when others attempt to probe into the depths of the middleware to determine if the solution is the right fit for your impending product upgrade.

How would you mitigate the risk that your maintenance costs would go up instead of down if you switched over to the new middleware solution? Would you take the middleware development team’s word for it? What if someone proposed prototyping and exploring an alternative solution that he/she thinks would better satisfy your product upgrade goals? In summary, how would you decrease the chance of making a costly mistake?

Exploring Processor Loading

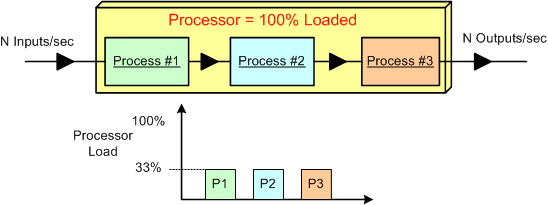

Assume that we have a data-centric, real-time product that: sucks in N raw samples/sec, does some fancy proprietary processing on the input stream, and outputs N value-added measurements/sec. Also assume that for N, the processor is 100% loaded and the load is equally consumed (33.3%) by three interconnected pipeline processes that crunch the data stream.

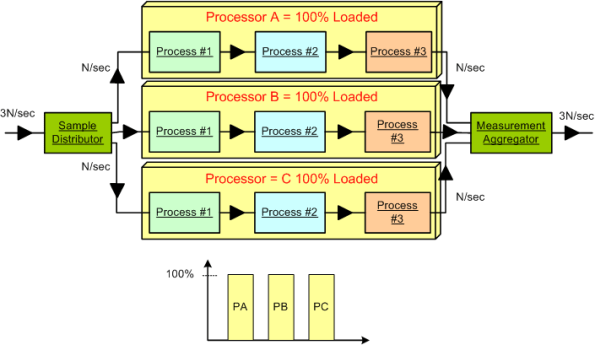

Next, assume that a new, emerging market demands a system that can handle 3*N input samples per second. The obvious solution is to employ a processor that is 3 times as fast as the legacy processor. Alternatively, (if the nature of the application allows it to be done) the input data stream can be split into thirds , the pipeline can be cloned into three parallel channels allocated to 3 processors, and the output streams can be aggregated together before final output. Both the distributor and the aggregator can be allocated to a fourth system processor or their own processors. The hardware costs would roughly quadruple, the system configuration and control logic would increase in complexity, but the product would theoretically solve the market’s problem and produce a new revenue stream for the org. Instead of four separate processor boxes, a single multi-core (>= 4 CPUs) box may do the trick.

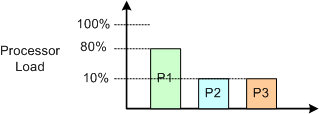

We’re not done yet. Now assume that in the current system, process #1 consumes 80% of the processor load and, because of input sample interdependence, the input stream cannot be split into 3 parallel streams. D’oh! What do we do now?

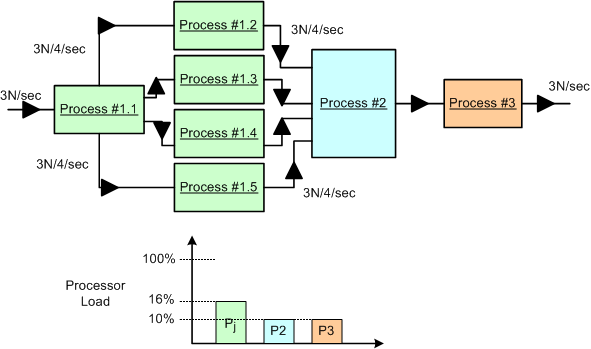

One approach is to dive into the algorithmic details of the P1 CPU hog and explore parallelization options for the beast. Assume that we are lucky and we discover that we are able to divide and conquer the P1 oinker into 5 equi-hungry sub-algorithms as shown below. In this case, assuming that we can allocate each process to its own CPU (multi-core or separate boxes), then we may be done solving the problem at the application layer. No?

Do you detect any major conceptual holes in this blarticle?

Archeosclerosis

Archeosclerosis is sclerosis of the software architecture. It is a common malady that afflicts organizations that don’t properly maintain and take care of their software products throughout the lifecycle.

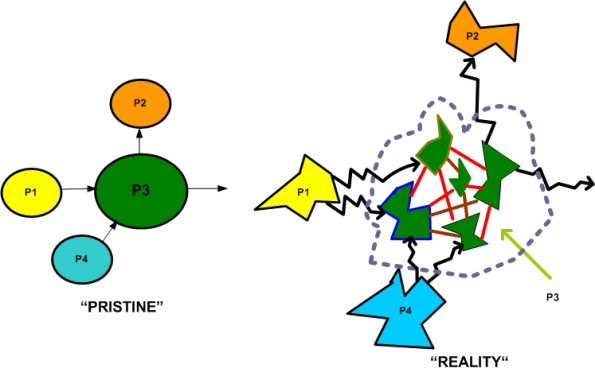

The time lapsed figure below shows the devastation caused by the failure to diligently keep entropy growth in check over the lifetime of a product. On the left, we have a four process application program that satisfies a customer need. On the right, we have a snapshot of the same program after archeosclerosis has set in.

Usually, but not always, the initial effort to develop the software yields a clean design that’s easy to maintain and upgrade. Over time, as new people come on board and the original developers move on to other assignments, the structure starts turning brittle. Bug fixes and new feature additions become swashbuckling adventures into the unknown and lessons in futility.

Fueled by schedule pressure and the failure of management to allocate time for periodic refactoring, developers shoehorn in new interfaces and modules. Pre-existing components get modified and lengthened. The original program structure fragments and the whole shebang morphs into a jagged quagmire.

Of course, the program’s design blueprints and testing infrastructure suffer from neglect too. Since they don’t directly generate revenue, money, time, and people aren’t allocated to keep them in sync with the growing software hairball. Besides, since all resources are needed to keep the house of cards from collapsing, no resources can be allocated to these or any other peripheral activities.

As long as the developer org has a virtual monopoly in their market, and the barriers to entry for new competitors are high, the company can stay in business, even though they are constantly skirting the edge of disaster.