Archive

Unjustifiable Precision

In “Object-Oriented Analysis and Design with Applications“, Grady Booch bluntly states:

Unjustifiable precision—in requirements or plans—has proven to be a substantial yet subtle recurring obstacle to success. Most of the time, early precision is just plain dishonest and serves to provide a façade for more progress of more quality than actually exists. – Grady Booch

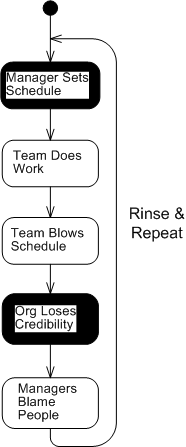

Pretty harsh, but wise, words, no? So, why do managers, directors, and executives repeatedly demand micro-granularized schedules and commitments from knowledge workers from day one throughout the life of a project?

- Because “that’s the way it has always been done“

- To maintain the illusion of control

- To flex their muscles and “hold people accountable” each time a micro-commitment is broken

Premature Optimization And Simplification

Premature optimization is the root of all evil – Donald Knuth

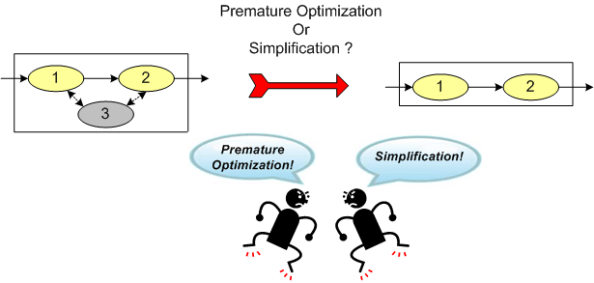

Most, if not all software developers will nod their heads in agreement with this technical proverb. However, as you may have personally experienced, one man’s premature optimization is another man’s simplification. Some people, especially BMs and BMWs shackled from above with a “schedule is king; what is quality?” mindset, will use that unspoken mantra as a powerful weapon (from a well stocked arsenal) to resist any change – all the while espousing “we’re agile and we embrace change“. Lemme give you a hypothetical example.

Assume that you’re working on a project and you discover that you can remove some domain layer code with no impact on the logical correctness of the system’s output. Furthermore, you discover that removal of the code, since it is used many times throughout the BBoM code base, will increase throughput and reduce latency. A win-win situation, right?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that’s not there – because it’s not needed. – Unknown

Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. – Antoine de Saint-Exupery

OK, so:

- you disclose your discovery to the domain “experts”,

- they whole-heartedly agree and thank you,

- you remove the code, and all is well.

Well, think again. Here’s what may happen:

- you disclose your discovery to the domain “experts”,

- you receive silence (because you’re not a member of the domain layer “experts” guild),

- you persist like a gnat until the silence cannot be maintained,

- you’re “told” that your proposal is a pre-mature optimization,

- you say “WTF?” to yourself, you fire a verbal cruise missile at the domain experts’ bunker, and you move on.

Illusion, Not Amplification

The job of the product development team is to engineer the illusion of simplicity, not to amplify the perception of complexity.

Software guru Grady Booch said the first part of this quote, but BD00 added the tail end. Apple Inc.’s product development org is the best example I can think of for the Booch part of the quote, and the zillions of mediocre orgs “out there” are a testament to the BD00 part.

According to Warren Buffet, the situation is even worse:

There seems to be some perverse human characteristic that likes to make easy things difficult. – Warren Buffet

Translated to BD00-lingo:

Engineers like to make make easy things difficult, and difficult things incomprehensible.

Why do they do it? Because:

A lot of people mistake unnecessary complexity for sophistication. – Dan Ward

Conclusion:

The quickest routes to financial ruin are: wine, women, gambling….. and engineers

Unavailable For Business

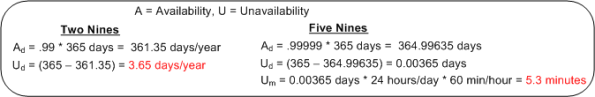

The availability of a system is usually specified in terms of the “number of nines” it provides. For example, a system with an availability specification of 99.99 provides “two nines” of availability. As the figure below shows, a service that is required to provide five nines of availability can only be unavailable 5.3 minutes per year!

Like most of the “ilities” attributes, the availability of any non-trivial system composed of thousands of different hardware and software components is notoriously difficult and expensive to predict or verify before the system is placed into operation. Thus, systems are deployed and fingers crossed in the hope that the availability it provides meets the specification. D’oh!

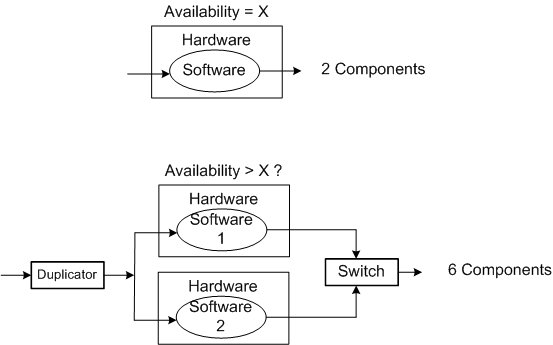

One way of supposedly increasing the availability of a system is to add redundancy to its design (see the figure below). But redundancy adds more complex parts and behavior to an already complex system. The hope is that the increase in the system’s unavailability and cost and development time caused by the addition of redundant components is offset by the overall availability of the system. Redundancy is expensive.

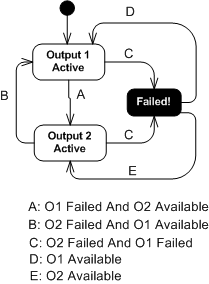

As you might surmise, the switch in the redundant system above must be “smart“. During operation, it must continuously monitor the health of both output channels and automatically switch outputs when it detects a failure in the currently active channel.

The state transition diagram below models the behavior required of the smart switch. When a switchover occurs due to a detected failure in the active channel, the system may become temporarily unavailable unless the redundant subsystem is operating as a hot standby (vs. cold standby where output is unavailable until it’s booted up from scratch). But operating the redundant channel as a hot standby stresses its parts and decreases overall system availability compared to the cold spare approach. D’oh!

Another big issue with adding redundancy to increase system availability is, of course, the BBoM software. If the BBoM running in the redundant channel is an exact copy of the active channel’s software and the failure is due to a software design or implementation defect (divide by zero, rogue memory reference, logical error, etc), that defect is present in both channels. Thus, when the switch dutifully does its job and switches over to the backup channel, it’s output may be hosed too. Double D’oh! To ameliorate the problem, a “software 2” component can be developed by an independent team to decrease the probability that the same defect is inserted at the same place. Talk about expensive?

Achieving availability goals is both expensive and difficult. As systems become more complex and human dependence on their services increases, designing, testing, and delivering highly available systems is becoming more and more important. As the demand for high availability continues to ooze into mainstream applications, those orgs that have a proven track record and deep expertise in delivering highly available systems will own a huge competitive advantage over those that don’t.

Learn To Estimate?

Item number 50 in “97 Things Every Programmer Should Know” is titled:

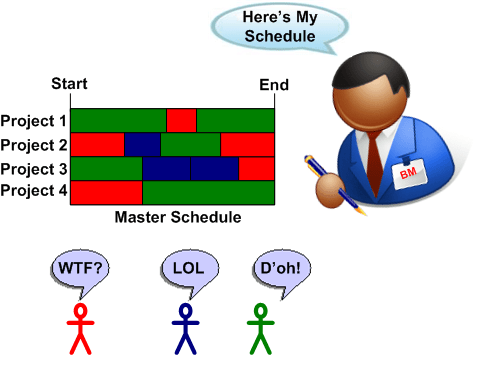

Since most schedules magically appear from the heavens without any input from below, why is there a need to learn how to estimate? If, by chance, schedule inputs ARE solicited from those who will do the work, they’re often ignored since heavenly commitments have already been made behind the scenes.

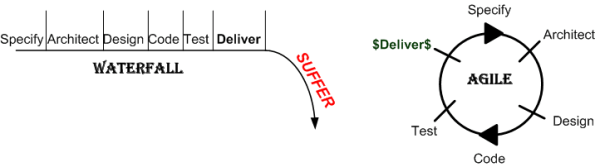

Deliverance

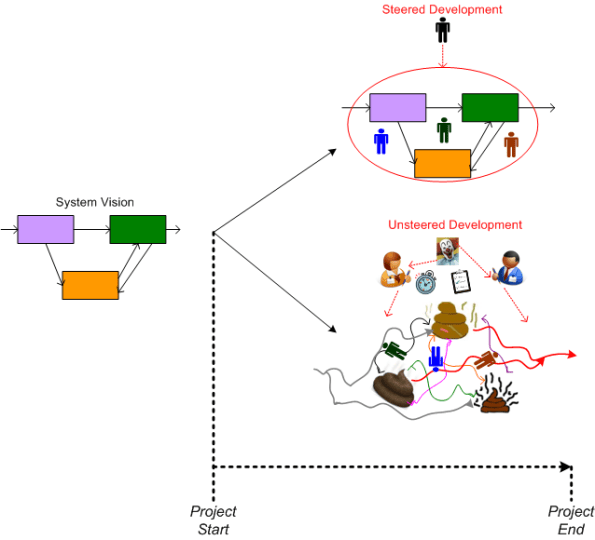

Steered, Or Unsteered

Complicated != Complex

For the non-geeks reading this post, the “!=” symbol is the C++ programming language token for “not equal“.

It seems like a lot of people think that classifying something as “complex” is the same as calling it “complicated“, and vice-versa. That conclusion can be, and often is, true, but it can also be false. I associate “complicated” with “not-understandable” – except to a select few experts. I think of “complex” to be the equivalent of something like “intricately elegant” and understandable to far more people than just experts.

Let’s take an example to illuminate my viewpoint. Assume that the black box system below functions delightfully. It’s reliable, responsive, easy to learn, and does what its users want without frustrating them in the slightest.

Now, in terms of complicated and complex, consider what the system may look like under the covers:

Now, in terms of complicated and complex, consider what the system may look like under the covers:

Of course, most users don’t give a shite what goes on under the covers, but the designing org and its people better well know what does – unless they luckily don’t have any competition to deal with, and hence, have their customers in a vice grip.

You see, at some point in time, the users will want improvements to the system as their needs evolve. If the original team of builders of implementation #1 are the only people who know the (so-called) design well enough to change it without breaking any existing capabilities, then the development org is hosed if those people leave. In effect, the org is held hostage by a small cadre of people. D’oh!

In the complex-complex implementation on the far right, even if the original builders leave the development org, the (relatively) elegant and well thought out design structure facilitates easy on-boarding of replacement builders. As an added bonus, the effort needed to add features and enhancements to the product is way less costly and risky than the other jaggedly complicated implementations.

So, given the portfolio of products in your org, how would you assess them in terms of the complexity and complicated attributes? If, and it’s probably a big IF, you could publicly communicate your assessment without fear of marginalization, or worse, how many people in your org do you think would publicly agree with your assessment? Uh, how abut privately? Would the number of public “agreers” match the number of private “agreers“?

Seven Unsurprising Findings

In the National Acadamies Press’s “Summary of a Workshop for Software-Intensive Systems and Uncertainty at Scale“, the Committee on Advancing Software-Intensive Systems Producibility lists 7 findings from a review of 40 DoD programs.

- Software requirements are not well defined, traceable, and testable.

- Immature architectures; integration of commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) products; interoperability; and obsolescence (the need to refresh electronics and hardware).

- Software development processes that are not institutionalized, have missing or incomplete planning documents, and inconsistent reuse strategies.

- Software testing and evaluation that lacks rigor and breadth.

- Lack of realism in compressed or overlapping schedules.

- Lessons learned are not incorporated into successive builds—they are not cumulative.

- Software risks and metrics are not well defined or well managed.

Well gee, do ya think they missed anything? What I’d like to know is what, if anything, they found right with those 40 programs. Anything? Maybe that would help more than ragging on the same issues that have been ragged on for 40 years.

My fave is number five (with number 1 a close second). When schedules concocted by non-technical managers without any historical backing or input from the people who will be doing the work are publicly promised to customers, how can anyone in their right mind assert that they’re “realistic“? The funny thing is, it happens all the time with nary a blink – until the fit hits the shan, of course. D’oh!

Meeting schedules based on historically tracked data and input from team members is challenging enough, but casting an unsubstantiated schedule in stone without an explicit policy of periodically reassessing it on the basis of newly acquired knowledge and learning as a project progresses is pure insanity. Same old, same old.

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by. – Douglas Adams

Requirements Stability

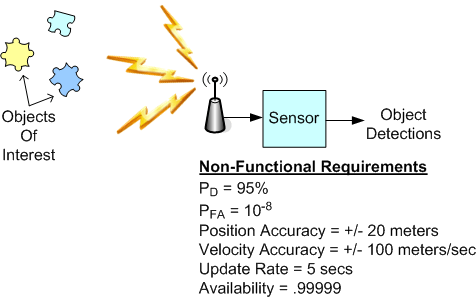

Over the years, I’ve been assigned to the roles of specifier, designer, documenter, writer, and maintainer of source code for radar sensor systems that are used in safety-critical applications. These sensors get deployed in noisy, interference-infested environments and they must perform at high levels of availability and with great fidelity.

The figure below shows a generic sensor system context diagram along with some typical non-functional requirements (with made-up values) that are critical for customer acceptance. My experience has indicated that once these black-box level requirements are specified, they rarely change. Thus, the agile war cry to continuously “embrace requirements change” may not fully apply to the development of this class of systems, no?

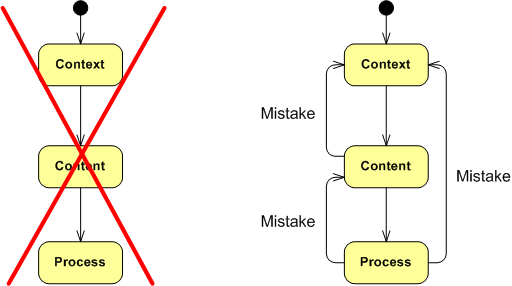

The point I’m trying to make here is to be wary of morphing into a lap-dog zealot for any technique, process, method, or practice – which includes the hallowed “agile” brand. For a long time, my motto (thanks to the work of W. L. Livingston and John Warfield) has been: Context, Content, and then Process (CCP). Synthesize an understanding of the problem context, design the content of the solution (structure and behavior), and only then design the solution construction process – tailored to the context and content. Of course, since mistakes and errors will be made during the journey, backtracking and iterative convergence are expected. Thus, “embrace mistakes, errors, backtracking, and iteration” is my war cry. What’s yours? What’s your org’s?