Archive

Functional Allocation III

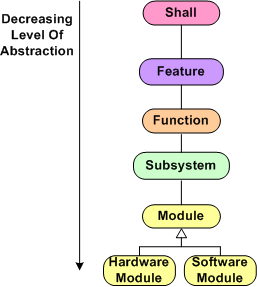

The figure below shows the movement from the abstract to the concrete through a nested “allocation” process designed for big and complex products (thus, hackers and duct-tapers need not apply). “Shalls” are allocated to features, which are allocated to functions, which are allocated to subsystems, which are allocated to hardware and software modules. Since allocation is labor intensive, which takes time, which takes money, are all four levels of allocation required? Can’t we just skip all the of the intermediate levels, allocate “shalls” to HW/SW modules, and start iteratively building the system pronto? Hmmm. The answer is subjective and, in addition to product size/complexity, it depends on many corpo-specific socio-technical factors. There is no pat answer.

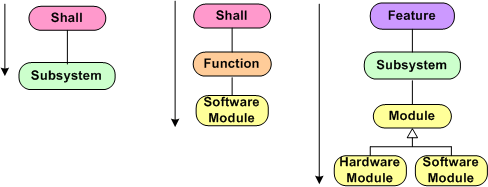

The figure below shows three variations derived from the hypothetical six-level allocation reference template. In the left-most process, two or more product subsystems that will (hopefully) satisfy a pre-existing set of “shalls” are conceived. At the end of the allocation process, the specification artifacts are released to teams of people “allocated” to each subsystem and the design/construction process continues. In the middle process, each SW module, along with the set of shalls and functions that it is required to implement is allocated to a SW developer. In the right process, which, in addition to custom software requires the creation of custom HW, the specification artifacts are allocated to various SW and HW engineers. (Since multiple individuals are involved in the development of the product, the definition of all entity-to-entity interfaces is at least as crucial as the identification and definition of the entities themselves, but that is a subject for another future post.)

Which process variation, if any, is “best”? Again, the number of unquantifiable socio-technical factors involved can make the decision daunting. The sad part is, in order to avoid thinking and making a conscious decision, most corpo orgs ram the full 6 level process down their people’s throats no matter what. To pour salt on the wound, management, which is always on the outside and looking-in toward the development teams, piles on all kinds of non-value-added byzantine approval procedures while simultaneously pounding the team(s) with schedule pressure to compplete. If you’re on the inside and directly creating or indirectly contributing to value creation, it’s not pretty. Bummer.

Functional Allocation II

Assume that you’re lucky and your company has a standard, generic product breakdown structure as follows:

- Product

- Functions

- Subsystems

- Configuration Items (Hardware and Software modules)

In order to achieve business success, an operating product needs to perform the functions that a user needs or wants for some reason. The functions are implemented by the number of, and interconnections between, the product subsystems. The subsystems are comprised of the hardware and software modules that animate the product.

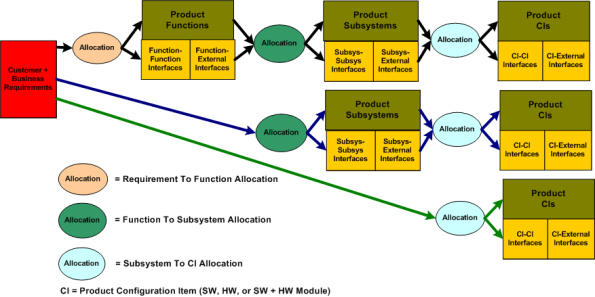

Depending on the complexity of the new product that is required to be developed, between one and three “allocation” paths from concept to product can be pursued. The figure below shows these paths.

If the problem that the product is required to control or solve is simple, the relatively short bottom path can be selected. If the finished aggregation of CIs do their intended job of seamlessly and elegantly supplying users with the functionality that they want/need, then the product will, in all likelihood, be successful. Profits will flow and customers will be happy. Classic win-win.

If the problem is complex, then the top path should be followed. Consciously or unconsciously pursuing the bottom path for complex products can, and usually is, disasterous. At best, money will be lost. At worst, people can die as a result of the end product’s failure to do what it was intended to do. Even if the top path is correctly chosen, failure to execute the process effectively can produce the same result as choosing the wrong bottom path. For success, the product and the “allocation” process must match. Success won’t be guaranteed, but the likelihood of success will increase.

So, what can cause a business failure even when the product and process are correctly matched at the outset? The list of reasons is long. Here are just a few that come to mind:

- Technical incompetence

- Managerial incompetence

- Massive external or internal schedule pressure that leads to corner-cutting

- Inter and/or intra-group rivalries naturally encouraged by hierarchically structured organizations of rank and privilege.

- An unfair reward system

- An obsession with following a rigid, micro-prescribed process to the letter of the law (dotting all the i’s and crossing all the t’s)

In summary, a product-process mismatch virtually guarantees long term business failure, but a product-process match may, just may, result in business success. The odds seem to be stacked in favor of failure. Bummer.

Functional Allocation I

Some system engineering process descriptions talk about “Functional Allocation” as being one of the activities that is performed during product development. So, what is “Functional Allocation”? Is it the allocation of a set of interrelated functions to a set of “something else”? Is it the allocation of a set of “something else” to a set of function(s)? Is it both? Is it done once, or is it done multiple times, progressing down a ladder of decreasing abstraction until the final allocation iteration is from something abstract to something concrete and physically measurable?

I hate the word “allocation”. I prefer the word “design” because that’s what the activity really is. Given a specific set of items at one level of abstraction, the “allocator” must create a new set of items at the next lower level of abstraction. That seems like design to me, doesn’t it? Depending on the nature and complexity of the product under development, conjuring up the next lower level set of items may be very difficult. The “allocator” has an infinite set of items to consciously choose from and purposefully interconnect. “Allocation” implies a bland, mechanistic, and deterministic procedure of apportioning one set of given items to another different set of given items. However, in real life only one set of items is “given” and the other set must be concocted out of nowhere.

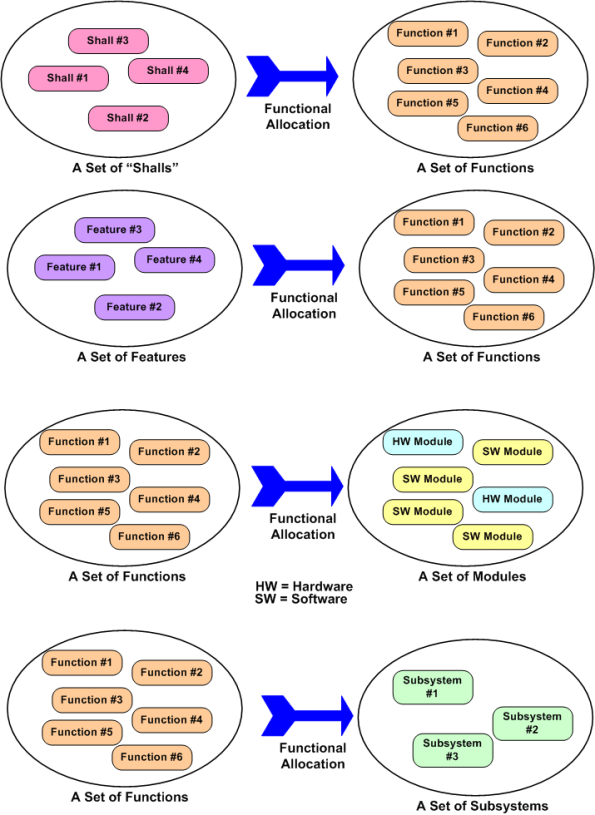

The figure below shows four different types of functional allocations: shalls-to-functions, features-to-functions, functions-to-modules, and functions-to-subsystems. Each allocation example has a set of functions involved. In the first two examples, the set of functions have been allocated “to”, and in the last two examples, the set of functions have been allocated “from”.

So, again I ask, what is functional allocation? To managers who love to remove people from the loop and automate every activity they possibly can to reduce costs, can human beings ever be removed from the process of functional allocation? If you said no, then what can you do to help make the process of allocation more efficient?

Product Development Systems

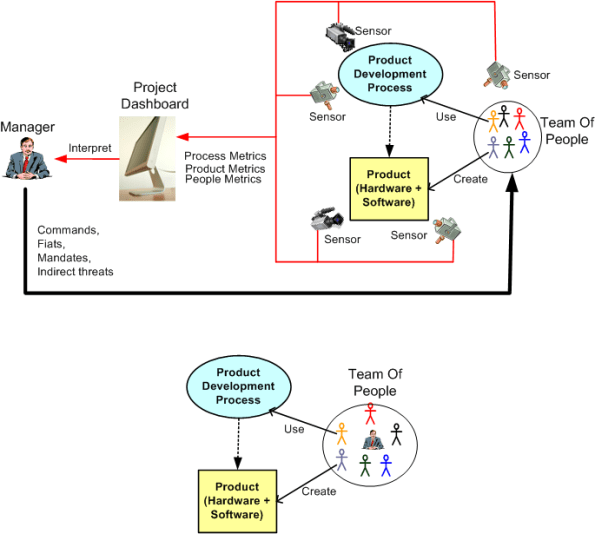

The figure below shows two (out of a possibly infinite number of) product development systems. Which one will produce the higher quality, lower cost product in the shortest time? Would a hybrid system be better?

How And What

“Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.” – George S. Patton

One of my pet peeves is when a bozo manager dictates the how, but has no clue of the what – which he/she is supposed to define:

“Here’s how you’re gonna create the what (whatever the what ends up being): You will coordinate Fagan inspections of your code, write code using Test First Design, comply with the corpo coding standards, use the corpo UML tool, run the code through a static analyzer, write design and implementation documents using the corpo templates, yada-yada-yada. I don’t know or care what the software is supposed to do, what type of software it is, or how big it will end up being, but you shall do all these things by this XXX date because, uh, because uh, be-be-because that’s the way we always do it. We’re not burger king, so you can’t have it your way.”

Focusing on the means regardless of what the ends are envisioned to be is like setting a million monkeys up with typewriters and hoping they will produce a Shakespear-ian masterpiece. It’s a failure of leadership. On the other hand, allowing the ends to be pursued without some constraints on the means can lead to unethical behavior. In both cases, means-first or ends-first, a crappy outcome may result.

On the projects where I was lucky to be anointed the software lead in spite of not measuring up to the standard cookie cutter corpo leadership profile, I leaned heavily toward the ends-first strategy, but I tried to loosely constrain the means so as not to suffocate my team: “eliminate all compiler warnings, code against the IDD, be consistent with your coding style, do some kind of demonstrable unit and integration testing and take notes on how you did it.”