Archive

Islands Of Sanity

Via InformIT: Safari Books Online – 0201700735 – The C++ Programming Language, Special Edition, I snipped this quote from Bjarne Stroustrup, the creator of the C++ programming language:

“AT&T Bell Laboratories made a major contribution to this by allowing me to share drafts of revised versions of the C++ reference manual with implementers and users. Because many of these people work for companies that could be seen as competing with AT&T, the significance of this contribution should not be underestimated. A less enlightened company could have caused major problems of language fragmentation simply by doing nothing.”

There are always islands of sanity in the massive sea of corpocratic insanity. AT&T’s behavior at that time during the historical development of C++ showed that they were one of those islands. Is AT&T still one of those rare anomalies today? I don’t have a clue.

Another Bjarne quote from the book is no less intriguing:

“In the early years, there was no C++ paper design; design, documentation, and implementation went on simultaneously. There was no “C++ project” either, or a “C++ design committee.” Throughout, C++ evolved to cope with problems encountered by users and as a result of discussions between my friends, my colleagues, and me.”

WTF? Direct communication with users? And how can it be possible that no PMI trained generic project manager or big cheese executive was involved to lead Mr. Stroustrup to success? Bjarne should’ve been fired for not following the infallible, proven, repeatable, and continuously improving, corpo product development process. No?

Stacks And Icebergs

The picture below attempts to communicate the explosive growth in software infrastructure complexity that has taken place over the past few decades. The growth in the “stack” has been driven by the need for bigger, more capable, and more complex software-intensive systems required to solve commensurately growing complex social problems.

In the beginning there was relatively simple, “fixed” function hardware circuitry. Then, along came the programmable CPU (Central Processing Unit). Next, the need to program these CPUs to do “good things” led to the creation of “application software”. Moving forward, “operating system software” entered the picture to separate the arcane details and complexity of controlling the hardware from the application-specific problem solving software. Next, in order to keep up with the pace of growing application software size , the capability for application designers to spawn application tasks (same address space) and processes (separate address spaces) was designed into the operating system software. As the need to support geographically disperse, distributed, and heterogeneous systems appeared, “communication middleware software” was developed. On and on we go as the arrow of time lurches forward.

As hardware complexity and capability continues to grow rapidly, the complexity and size of the software stack also grows rapidly in an attempt to keep pace. The ability of the human mind (which takes eons to evolve compared to the rate of technology change) to comprehend and manage this complexity has been overwhelmed by the pace of advancement in hardware and software infrastructure technology growth.

Thus, in order to appear “infallibly in control” and to avoid the hard work of “understanding” (which requires diligent study and knowledge acquisition), bozo managers tend to trivialize the development of software-intensive systems. To self-medicate against the pain of personal growth and development, these jokers tend to think of computer systems as simple black boxes. They camouflage their incompetence by pretending to have a “high level” of understanding. Because of this aversion to real work, these dudes have no problem committing their corpocracies to ridiculous and unattainable schedules in order to win “the business”. Have you ever heard the phrase “aggressive schedule”?

“You have to know a lot to be of help. It’s slow and tedious. You don’t have to know much to cause harm. It’s fast and instinctive.” – Rudolph Starkermann

Don’t Be Late!

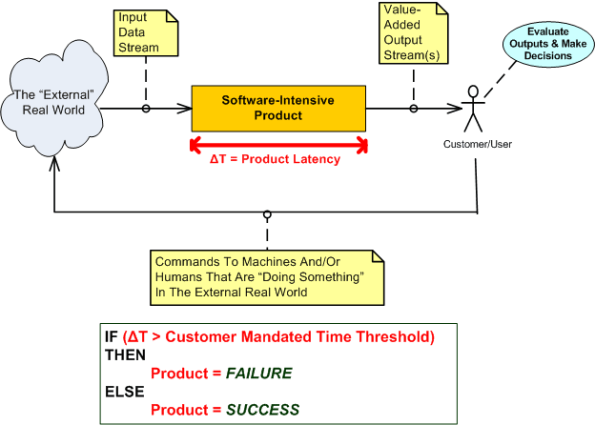

The software-intensive products that I get paid to specify, design, build, and test involve the real-time processing of continuous streams of raw input data samples. The sample streams are “scrubbed and crunched” in order to generate higher-level, human interpretable, value-added, output information and event streams. As the external stream flows into the product, some samples are discarded because of noise and others are manipulated with a combination standard and proprietary mathematical algorithms. Important events are detected by monitoring various characteristics of the intermediate and final output streams. All this processing must take place fast enough so that the input stream rate doesn’t overwhelm the rate at which outputs can be produced by the product; the product must operate in “real-time”.

The human users on the output side of our products need to be able to evaluate the output information quickly in order to make important and timely command and control decisions that affect the physical well-being of hundreds of people. Thus, latency is one of the most important performance metrics used by our customers to evaluate the acceptability of our products. Forget about bells and whistles, exotic features, and entertaining graphical interfaces, we’re talking serious stuff here. Accuracy and timeliness of output are king.

Latency (or equivalently, response time) is the time it takes from an input sample or group of related samples to traverse the transformational processing path from the point of entry to the point of egress through the software-dominated product “box” or set of interconnected boxes. Low latency is good and high latency is bad. If product latency exceeds a time threshold that makes the output effectively unusable to our customers , the product is unacceptable. In some applications, failure of the absolute worst case latency to stay below the threshold can be the deal breaker (hard real time) and in other applications the average latency must not exceed the threshold xx percent of the time where xx is often greater than 95% (soft real time).

Latency is one of those funky, hard-to-measure-until-the-product-is-done, “non-functional” requirements. If you don’t respect its power to make or break your wonderful product from the start of design throughout the entire development effort, you’ll get what you deserve after all the time and money has been spent – lots of rework, stress, and angst. So, if you work on real-time systems, don’t be late!

Four Or Two?

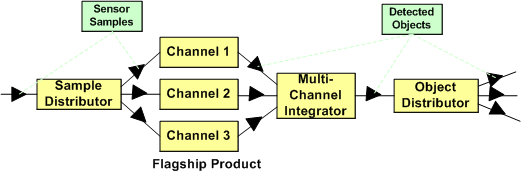

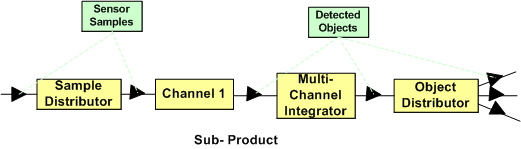

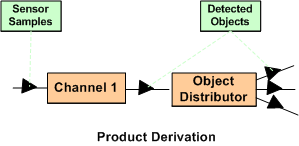

Assume that the figure below represents the software architecture within one of your flagship products. Also assume that each of the 6 software components are comprised of N non-trivial SLOC (Source Lines Of Code) so that the total size of the system is 6N SLOC. For the third assumption, pretend that a new, long term, adjacent market opens up for a “channel 1” subset of your product.

To address this new market’s need and increase your revenue without a ton of investment, you can choose to instantiate the new product from your flagship. As shown in the figure below, if you do that, you’ve reduced the complexity of your new product addition by 1/3 (6N to 4N SLOC) and hence, decreased the ongoing maintenance cost by at least that much (since maintainability is a non-linear function of software size).

Nevertheless, your new product offering has two unneeded software components in its design: the “Sample Distributor” and the “Multi-Channel Integrator”. Thus, if as the diagram below shows, you decide to cut out the remaining fat (the most reliable part in a system is the one that’s not there – because it’s not needed), you’ll deflate your long term software maintenance costs even further. Your new product portfolio addition would be 1/3 the original size (6N to 2N SLOC) of your flagship product.

If you had the authority, which approach would you allocate your resources to? Would you leave it to chance? Is the answer a no brainer, or not? What factors would prevent you from choosing the simpler two component solution over the four component solution? What architecture would your new customers prefer? What would your competitors do?

Sum Ting Wong

- SYS = Systems

- SW = Software

- HW = Hardware

When the majority of SYS engineers in an org are constantly asking the HW and SW engineers how the product works, my Chinese friend would say “sum ting (is) wong”. Since they’re the “domain experts”, the SYS engineers supposedly designed and recorded the product blueprints before the box was built. They also supposedly verified that what was built is what was specified. To be fair, if no useful blueprints exist, then 2nd generation SYS engineers who are assigned by org corpocrats to maintain the product can’t be blamed for not understanding how the product works. These poor dudes have to deal with the inherited mess left behind by the sloppy and undisciplined first generation of geniuses who’ve moved on to cushy “staff” and “management” positions.

Leadership is exploring new ground while leaving trail markers for those who follow. Failing to demand that first generation product engineers leave breadcrumbs on the trail is a massive failure of leadership.

If the SYS engineers don’t know how the product works at the “white box” level of detail, then they won’t be able to efficiently solve system performance problems, or conceive of and propose continuous improvements. The net effect is that the mysterious “black box” product owns them instead of vice versa. Like an unloved child, a neglected product is perpetually unruly. It becomes a serial misbehaver and a constant source of problems for its parents; leaving them confounded and confused when problems manifest in the field.

A corpocracry with leaders that are so disconnected from the day-to-day work in the bowels of the boiler room that they don’t demand system engineering ownership of products, get what they deserve; crappy products and deteriorating financial performance.

My “Status” As Of 09-27-09

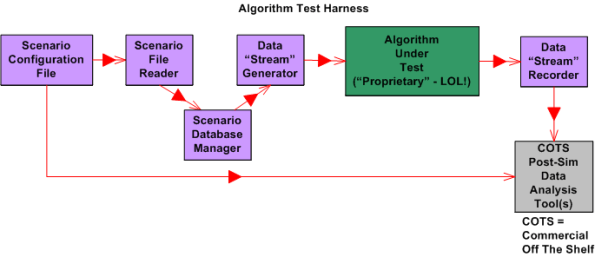

I recently finished a 2 month effort discovering, developing, and recording a state machine algorithm that produces a stream of integrated output “target” reports from a continuous stream of discrete, raw input message fragments. It’s not rocket science, but because of the complexity of the algorithm (the devil’s always in the details), a decision was made to emulate this proprietary algorithm in multiple, simulated external environmental scenarios. The purpose of the emulation-plus-simulation project is to work out the (inevitable) kinks in the algorithm design prior to integrating the logic into an existing product and foisting it on unsuspecting customers :^) .

The “bent” SysML diagram below shows the major “blocks” in the simulator design. Since there are no custom hardware components in the system, except for the scenario configuration file, every SysML block represents a software “class”.

Upon launch, the simulator:

- Reads in a simple, flat, ASCII scenario configuration file that specifies the attributes of targets operating in the simulated external environment. Each attribute is defined in terms of a <name=value> token pair.

- Generates a simulated stream of multiplexed input messages emitted by the target constellation.

- Demultiplexes and processes the input stream in accordance with the state machine algorithm specification to formulate output target reports.

- Records the algorithm output target report stream for post-simulation analysis via Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) tools like Excel and MATLAB.

I’m currently in the process of writing the C++ code for all of the components except the COTS tools, of course. On Friday, I finished writing, unit testing, and integration testing the “Simulation Initialization” functionality (use case?) of the simulator.Yahoo!

The diagram below zooms in on the front end of the simulator that I’ve finished (100% of course) developing; the “Scenario File Reader” class, and the portion of the in-memory “Scenario Database Manager” class that stores the scenario configuration data in the two sub-databases.

The next step in my evil plan (moo ha ha!) is to code up, test, and integrate the much-more-interesting “Data Stream Generator” class into the simulator without breaking any of the crappy code that has already been written. 🙂

If someone (anyone?) actually reads this boring blog and is interested in following my progress until the project gets finished or canceled, then give me a shoutout. I might post another status update when I get the “Data Stream Generator” class coded, tested, and integrated.

What’s your current status?

90 Percent Done

In order for those in charge (and those who are in charge of those who are in charge ad infinitum) to track and control a project, someone has to estimate when the project will be 100% complete. For any software development project of non-trivial complexity, it doesn’t matter who conjures up the estimate, or what drugs they were on when they verbalized it, the odds are huge that the project will be underestimated. That’s because in most corpo command and control hierarchies, there is always implicit pressure to underestimate the effort needed to “get it done”. After all, time is money and everyone wants to minimize the cost to “get it done”. Even though everybody smells the silent-but-deadly stank in the air and knows that’s how the game is played, everybody pretends otherwise.

The graph below shows a made up example (like John Lovitt, I’m a patholgical liar who makes everything up, so don’t believe a word I say) of a project timeline. On day zero, the obviously infallible project manager (if you browse linkedin.com, no manager has ever missed a due date) plots a nice and tidy straight (blue) line to the 100% done date. During the course of executing the project, regular status is taken and plotted as the “actual” progress (red) line so that everybody who is important in the company can know what’s going on.

For the example project modeled by the graph, the actual progress starts deviating from the planned progress on day one. Of course, since the vast majority of project (and product and program) managers are klueless and don’t have the expertise to fix the deficit, the gap widens over time. On really dorked up projects, the red line starts above the blue line and the project is ahead of schedule – whoopee!

At around the 90-95% scheduled-to-be-done time, something strange (well, not really strange) happens. Each successive status report gets stuck at 90% done. Those in charge (and those who are in charge of those who are in charge ad infinitum) say “WTF?” and then some sort of idiotic and ineffective action, like applying more pressure or requiring daily status meetings or throwing more DICs (Dweebs In the Cellar) on the project, is taken. In rare cases, the project (or product or program) manager is replaced. It’s rare because project (and product and program) managers and those who appoint them are infallible, remember?

So, is “continuous replanning”, where new scheduled-to-be-done dates are estimated as the project progresses, the answer? It can certainly help by reducing the chance of a major “WTF” discontinuity at the 90% done point. However, it’s not a cure all. As long as the vast majority of project (and product and program) managers maintain their attitude of infallibility and eschew maintaining some minimum level of technical competence in order to sniff out the real problems, help the team, and make a difference, it’ll remain the same-old same-old forever. Actually, it will get worse because as the inherent complexity of the projects that a company undertakes skyrockets, this lack of leadership excellence will trigger larger performance shortfalls. Bummer.

Architectural, Mechanistic, And Detailed

Bruce Powel Douglass is one of my favorite embedded systems development mentors. One of his ideas is to categorize the activity of design into three levels of increasingly detailed abstraction:

- Architectural (5 views)

- Mechanistic

- Detailed

The SysML figure below tries to depict the conceptual differences between these levels. (Even if you don’t know the SysML, can you at least viscerally understand the essence of what the drawings are attempting to communicate?)

Since the size, algorithmic density, and safety critical nature of the software intensive systems that I’ve helped to develop require what the agile community mocks as BDUF (Big Design Up Front), I’ve always communicated my “BDUF” designs in terms of the first and third abstractions. Thus, the mechanistic design category is sort of new to me. I like this category because it shortens the gulf of understanding between the architectural and the detailed design levels of abstraction. According to Mr. Douglass, “mechanistic design” is the act of optimizing a system at the level of an individual collaboration ( a set of UML classes or SysML blocks working closely together to realize a single use case). From now on, I’m gonna follow his three tier taxonomy in communicating future designs, but only when it’s warranted, of course (I’m not a religious zealot for or against any method), .

BTW, if you don’t do BDUF, you might get CUDO (Crappy and Unmaintanable Design Out back). Notice that I said “might” and not “will”.

The Vault Of No Return

In big system development projects, continuous iteration and high speed error removal are critical to the creation of high quality products. Thus, it’s essential to install flexible and responsive Configuration Management and Quality Assurance (CMQA) support systems that provide easy access to intermediate work products that (most definitely) will require rework as a result of ongoing learning and new knowledge acquisition.

As opposed to virtually all methodologies that exhort early involvement of the CMQA folks in projects, I (but who the hell am I?) advise you to consider otherwise. If you have the power (and sadly, most people don’t), then keep the corpo CMQA orgs out of your knickers until the project enters the production phase. Why? Because I assert that most big company CMQA orgs innocently think they are the ends, and not a means. Thus, in order to project an illusion of importance, the org creates and enforces Draconian, Rube Goldberg-like, high latency, low value-added, schedule-busting procedures for storing work products in the vault of no return. Once project work products are locked in the vault, the amount of effort and time to retrieve them for error correction and disambiguation is so demoralizing and frustrating that most well-meaning information creators just give up. Sadly, instead of change management, most CMQA orgs unconsciously practice change prevention.

The figure below contrasts two different product developments in terms of when a CMQA org gets intertwined with the value creation project pipeline. The top half shows early coupling and the bottom half shows late coupling. Since upstream work products are used by downstream workgroups to produce the next stage’s outputs, the downstreamers will discover all kinds of errors of commission and (worse,) omission. However, since the project info has been locked in the vault of no return, if the culture isn’t one of infallible machismo, upstream producers and downstream consumers will circumvent the “system” and collaborate behind the scenes to fix mistakes and clarify ambiguities to increase quality. If and when that does happen, the low quality, vault-locked information gets out of synch with the informal and high quality information in the pipeline. Even though that situation is better than having both the vault and project pipeline filled with error infested information, post-delivery product maintenance teams will encounter outdated and incorrect blueprints when they retrieve the “formal” blueprints from the vault. Bummer.

UML and SysML Behavior Modeling

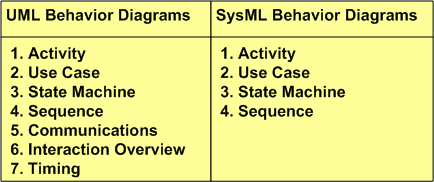

Most interesting systems exhibit intentionally (and sometimes unintentionally) rich behavior. In order to capture complex behavior, both the UML and its SysML derivative provide a variety of diagrams to choose from. As the table below shows, the UML defines 7 behavior diagram types and the SysML provides a subset of 4 of those 7.

Activity diagrams are a richer, more expressive enhancement to the classic, stateless, flowchart. Use case diagrams capture a graphical view of high level, text-based functional requirements. State machine diagrams are used to model behaviors that are a function of current inputs and past history. Sequence diagrams highlight the role of “time” in the protocol interactions between SysML blocks or UML objects.

What’s intriguing to me is why the SysML didn’t include the Timing diagram in its behavioral set of diagrams. The timing diagram emphasizes the role of time in a different and more precise way than the sequence diagram. Although one can express precise, quantitative timing constraints on a sequence diagram, mixing timing precision with protocol rules can make the diagram much more complicated to readers than dividing the concerns between a sequence diagram and timing diagram pair. Exclusion of the timing diagram is even more mysterious to me because timing constraints are very important in the design of hard/soft real-time systems. Incorrect timing behavior in a system can cause at least as much financial or safety loss as the production of incorrect logical outputs. Maybe the OMG and INCOSE will reconsider their decision to exclude the timing diagramin their next SysML revision?