Archive

iSpeed OPOS

A couple of years ago, I designed a “big” system development process blandly called MPDP2 = Modified Product Development Process version 2. It’s version 2 because I screwed up version 1 badly. Privately, I named it iSpeed to signify both quality (the Apple-esque “i”) and speed but didn’t promote it as such because it didn’t sound nerdy enough. Plus, I was too chicken to introduce the moniker into a conservative engineering culture that innocently but surely suppresses individuality.

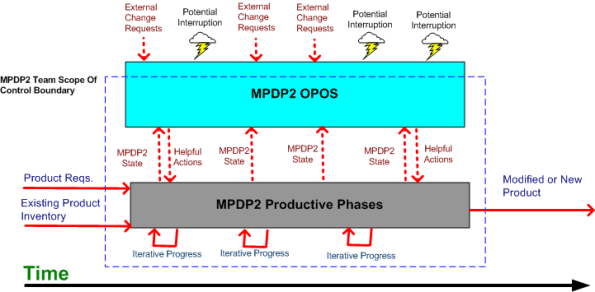

One of the MPDP2 activties, which stretches across and runs in parallel to the time sequenced development phases, is called OPOS = Ongoing Planning, Ongoing Steering. The figure below shows the OPOS activity gaz-intaz and gaz-outaz.

In the iSpeed process, the top priority of the project leader (no self-serving BMs allowed) is to buffer and shield the engineering team from external demands and distractions. Other lower priority OPOS tasks are to periodically “sample the value stream”, assess the project state, steer progress, and provide helpful actions to the multi-disciplined product development team. What do you think? Good, bad, fugly? Missing something?

Plumbers And Electricians

Putting an expert in one technical domain “in charge” of a big risky project that requires deep expertise in a different technical domain is like putting plumbers in charge of a team of electricians on a massive skyscraper electrical job – or vice versa. Putting a generic PMI or MBA trained STSJ in charge of a complex, mixed-discipline engineering product development project is even worse. When they don’t know anything about WTF they’re managing, how can innocently ignorant project “leaders”:

- Understand what needs to be done

- Know what information artifacts need to be generated along the way for downstream project participants

- Estimate and plan the work with reasonable accuracy

- Correctly interpret ongoing status so that they have an idea where the project is located in terms of cost, schedule, and quality

- Make effective mid-course corrections when things go awry and ambiguity reigns

- See through any bullshit used to camouflage shoddy work or to cut corners,

- Stop small but important problems from falling through the cracks and growing into ominously huge obstacles

- Perform the “verify” part of “trust but verify”.

Well, they can’t – no matter how many impressive and glossy process templates are stored in the standard corpo database to guide them. Thus, these poor dudes spend most of their time spinning out massive, impressive excel spreadsheets and microsoft project schedules so fine grained that they’re obsolete before they’re showcased to the equally clueless suits upstairs. But hey, everything looks good on the surface for a long stretch of time. Uh, until the fit hits the shan.

Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule

I read this Paul Graham essay quite a while ago; Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule, and I’ve been wanting to blog about it ever since. Recently, it was referred to me by others at least twice, so the time has come to add my 2 cents.

In his aptly titled essay, Paul says this about a manager’s schedule:

The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.

Regarding the maker’s schedule, he writes:

But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started. When you’re operating on the maker’s schedule, meetings are a disaster.

When managers graduate from being a maker and morph into bozos (of which there are legions), they develop severe cases of ADHD and (incredibly,) they “forget” the implications of the maker-manager schedule difference. For these self-important dudes, it’s status and reporting meetings galore so that they can “stay on top” of things and lead their teams to victory. While telling their people that they need to become more efficient and productive to stay competitive, they shite in their own beds by constantly interrupting the makers to monitor status and determine schedule compliance. The sad thing is that when the unreasonable schedules they pull out of their asses inevitably slip, the only technique they know how to employ to get back on track is the ratcheting up of pressure to “meet schedule”. They’re bozos, so how can anyone expect anything different – like asking how they could personally help out or what obstacles they can help the makers overcome. Bummer.

The Rise Of The “ilities”

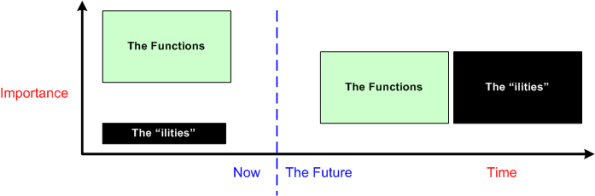

The title of this post should have been “The Rise Of Non-Functional Requirements“, but that sounds so much more gauche than the chosen title.

As software-centric systems get larger and necessarily more complex, they take commensurately more time to develop and build. Making poor up front architectural decisions on how to satisfy the cross-cutting non-functional requirements (scalability, distribute-ability, response-ability (latency), availability, usability, maintainability, evolvability, portability, secure-ability, etc.) imposed on the system is way more costly downstream than making bad up front decisions regarding localized, domain-specific functionality. To exacerbate the problem, the unglamorous “ilities” have been traditionally neglected and they’re typically hard to quantify and measure until the system is almost completely built. Adding fuel to the fire, many of the “ilities” conflict with each other (e.g. latency vs maintainability, usability vs. security). Optimizing one often marginalizes one or more others.

When a failure to meet one or more non-functional requirements is discovered, correcting the mistake(s) can, at best, consume a lot of time and money, and at worst, cause the project to crash and burn (the money’s gone, the time’s gone, and the damn thang don’t work). That’s because the mechanisms and structures used to meet the “ilities” requirements cut globally across the entire system and they’re pervasively weaved into the fabric of the product.

If you’re a software engineer trying to grow past the coding and design patterns phases of your profession, self-educating yourself on the techniques, methods, and COTS technologies (stay away from homegrown crap – including your own) that effectively tackle the highest priority “ilities” in your product domain and industry should be high on your list of priorities.

Because of the ubiquitous propensity of managers to obsess on short term results and avoid changing their mindsets while simultaneously calling for everyone else to change theirs, it’s highly likely that your employer doesn’t understand and appreciate the far reaching effects of hosing up the “ilities” during the front end design effort (the new age agile crowd doesn’t help very much here either). It’s equally likely that your employer ain’t gonna train you to learn how to confront the growing “ilities” menace.

Staffing Profiles

The figure below shows the classic smooth and continuous staffing profile of a successful large scale software system development project. At the beginning, a small cadre of technical experts sets the context and content for downstream activity and the group makes all the critical, far reaching architectural decisions. These decisions are documented in a set of lightweight, easily accessible, and changeable “artifacts” (I try to stay away from the word “documentation” since it triggers massive angst in most developers).

If the definitions of context and content for the particular product are done right, the major incremental development process steps that need to be executed will emerge naturally as byproducts of the effort. An initial, reasonable schedule and staffing profile can then be constructed and a project manager (hopefully not a BM) can be brought on-board to serve as the PHOR and STSJ.

Sadly, most big system developments don’t trace the smooth profiling path outlined above. They are “planned” (if you can actually call it planning) and executed in accordance with the figure below. No real and substantive planning is done upfront. The standard corpo big bang WBS (Work Breakdown Structure) template of analysis/SRR/design/PDR/CDR/coding/test is hastily filled in to satisfy the QA police force and a full, BM led team is blasted at the project. Since dysfunctional corpocracies have no capacity to remember or learn, the cycle of mediocre (at best) performance is repeated over and over and over. Bummer.

Spoiled And Lazy; Hungry And Energetic

A few years ago, I read an opinion piece regarding the demise of the US auto industry. The author stated that because they were spoon fed boatloads of money by the US government to design and build military hardware during WWII, the car companies morphed into spoiled and lazy sloths; they stopped innovating on their own nickel. Unless a sugar daddy (like the US government) was going to externally subsidize the effort, they weren’t gonna open the company coffers to develop new products or vastly improve their existing ones. Because of this overly conservative mindset (and the poo pooing away of Deming’s quality movement), the Japanese eventually blew right by the big three – even though their nation was decimated by the war and they had to start from scratch.

The same danger applies today, every day, to every company that builds things, especially big things, for government orgs. Understandably, since creating and continuously improving big complex systems requires big investments and big scary risks to be overcome, companies are loathe to pour money into what may eventually turn out to be an infinite rat hole. However, if all the competitors in the market space have the same welfare mindset, then no one will sprint out ahead of the pack and all participants may still prosper – until money gets tight. When the external dollar stream slows to a trickle, those (if any) competitors who’ve boldly invested in the future and successfully transformed their investments into product improvements and new product portfolio additions, rise to the top. It’s the hungry and energetic, not the spoiled and lazy, that continuously prosper through good times and bad.

Is your company spoiled and lazy, or hungry and energetic? If it’s the former, what actions does your company take when tough economic times emerge and the money stream slows?

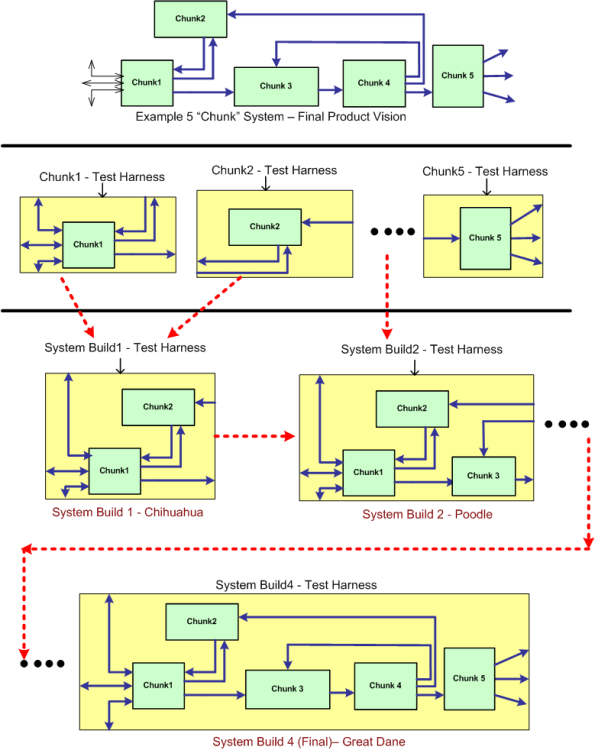

Incremental Chunked Construction

Assume that the green monster at the top of the figure below represents a stratospheric vision of a pipelined, data-centric, software-intensive system that needs to be developed and maintained over a long lifecycle. By data-centric, I mean that all the connectors, both internal and external, represent 24 X 7 real-time flows of streaming data – not “client requests” for data or transactional “services”. If the Herculean development is successful, the product will both solve a customer’s problem and make money for the developer org. Solving a problem and making money at the same time – what a concept, eh?

One disciplined way to build the system is what can be called “incremental chunked construction”. The system entities are called “chunks” to reinforce the thought that their granularity is much larger than a fine grained “unit” – which everybody in the agile, enterprise IT, transaction-centric, software systems world seems to be fixated on these days.

Follow the progression in the non-standard, ad-hoc diagram downward to better understand the process of incremental chunked development. It’s not much different than the classic “unit testing and continuous integration” concept. The real difference is in the size, granularity, complexity and automation-ability of the individual chunk and multi-chunk integration test harnesses that need to be co-developed. Often, these harnesses are as large and complex as the product’s chunks and subsystems themselves. Sadly, mostly due to pressure from STSJ management (most of whom have no software background, mysteriously forget repeated past schedule/cost performance shortfalls, and don’t have to get their hands dirty spending months building the contraption themselves), the effort to develop these test support entities is often underestimated as much as, if not more than, the product code. Bummer.

CCP

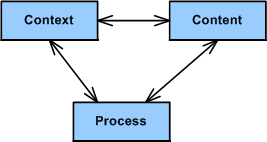

Relax right wing meanies, it’s not CCCP. It’s CCP, and it stands for Context, Content, and Process. Context is a clear but not necessarily immutable definition of what’s in and what’s out of the problem space. Content is the intentionally designed static structure and dynamic behavior of the socio-technical solution(s) to be applied in an attempt to solve the problem. Process is the set of development activities, tasks, and toolboxes that will be used to pre-test (simulate or emulate), construct, integrate, post-test, and carefully introduce the solution into the problem space. Like the other well-known trio, schedule-cost-quality, the three CCP elements are intimately coupled and inseparable. Myopically focusing on the optimization of one element and refusing to pay homage to the others degrades the performance of the whole.

I first discovered the holy trinity of CCP many years ago by probing, sensing, and interpreting the systems work of John Warfield via my friend, William Livingston. I’ve been applying the CCP strategy for years to technical problems that I’ve been tasked to solve.

You can start using the CCP problem solving process by diving into any of the three pillars of guidance. It’s not a neat, sequential, step-by-step process like those documented in your corpo standards database (that nobody follows but lots of experts are constantly wasting money/time to “improve”). It’s a messy, iterative, jagged, mistake discovering and correcting intellectual endeavor.

I usually start using CCP by spending a fair amount of time struggling to define the context; bounding, iterating and sketching fuzzy lines around what I think is in and what is out of scope. Next, I dive into the content sub-process; using the context info to conjure up solution candidates and simulate them in my head at the speed of thought. The first details of the process that should be employed to bring the solution out of my head and into the material world usually trickle out naturally from the info generated during the content definition sub-process. Herky-jerky, iterative jumping between CCH sub-processes, mental simulation, looping, recursion, and sketching are key activities that I perform during the execution of CCP.

What’s your take on CCP? Do you think it’s generic enough to cover a large swath of socio-technical problem categories/classes? What general problem solving process(es) do you use?

A Costly Mistake?

Assume the following:

- Your flagship software-intensive product has had a long and successful 10 year run in the marketplace. The revenue it has generated has fueled your company’s continued growth over that time span.

- In order to expand your market penetration and keep up with new customer demands, you have no choice but to re-architect the hundreds of thousands of lines of source code in your application layer to increase the product’s scalability.

- Since you have to make a large leap anyway, you decide to replace your homegrown, non-portable, non-value adding but essential, middleware layer.

- You’ve diligently tracked your maintenance costs on the legacy system and you know that it currently costs close to $2M per year to maintain (bug fixes, new feature additions) the product.

- Since your old and tired home grown middleware has been through the wringer over the 10 year run, most of your yearly maintenance cost is consumed in the application layer.

The figure below illustrates one “view” of the situation described above.

Now, assume that the picture below models where you want to be in a reasonable amount of time (not too “aggressive”) lest you kludge together a less maintainable beast than the old veteran you have now.

Cost and time-wise, the graph below shows your target date, T1, and your maintenance cost savings bogey, $75K per month. For the example below, if the development of the new product incarnation takes 2 years and $2.25 M, your savings will start accruing at 2.5 years after the “switchover” date T1.

Now comes the fun part of this essay. Assume that:

- Some other product development group in your company is 2 years into the development of a new middleware “candidate” that may or may not satisfy all of your top four prioritized goals (as listed in the second figure up the page).

- This new middleware layer is larger than your current middleware layer and complicated with many new (yet at the same time old) technologies with relatively steep learning curves.

- Even after two years of consumed resources, the middleware is (surprise!) poorly documented.

- Except for a handful of fragmented and scattered powerpoint files, programming and design artifacts are non-existent – showing a lack of empathy for those who would want to consider leveraging the 2 year company investment.

- The development process that the middleware team is using is fairly unstructured and unsupervised – as evidenced by the lack of project and technical documentation.

- Since they’re heavily invested in their baby, the members of the development team tend to get defensive when others attempt to probe into the depths of the middleware to determine if the solution is the right fit for your impending product upgrade.

How would you mitigate the risk that your maintenance costs would go up instead of down if you switched over to the new middleware solution? Would you take the middleware development team’s word for it? What if someone proposed prototyping and exploring an alternative solution that he/she thinks would better satisfy your product upgrade goals? In summary, how would you decrease the chance of making a costly mistake?

Exploring Processor Loading

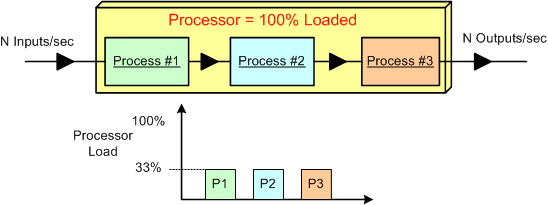

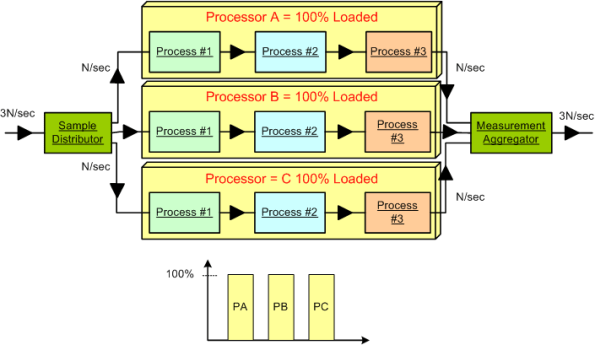

Assume that we have a data-centric, real-time product that: sucks in N raw samples/sec, does some fancy proprietary processing on the input stream, and outputs N value-added measurements/sec. Also assume that for N, the processor is 100% loaded and the load is equally consumed (33.3%) by three interconnected pipeline processes that crunch the data stream.

Next, assume that a new, emerging market demands a system that can handle 3*N input samples per second. The obvious solution is to employ a processor that is 3 times as fast as the legacy processor. Alternatively, (if the nature of the application allows it to be done) the input data stream can be split into thirds , the pipeline can be cloned into three parallel channels allocated to 3 processors, and the output streams can be aggregated together before final output. Both the distributor and the aggregator can be allocated to a fourth system processor or their own processors. The hardware costs would roughly quadruple, the system configuration and control logic would increase in complexity, but the product would theoretically solve the market’s problem and produce a new revenue stream for the org. Instead of four separate processor boxes, a single multi-core (>= 4 CPUs) box may do the trick.

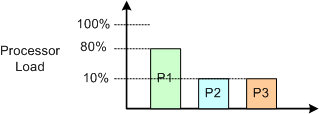

We’re not done yet. Now assume that in the current system, process #1 consumes 80% of the processor load and, because of input sample interdependence, the input stream cannot be split into 3 parallel streams. D’oh! What do we do now?

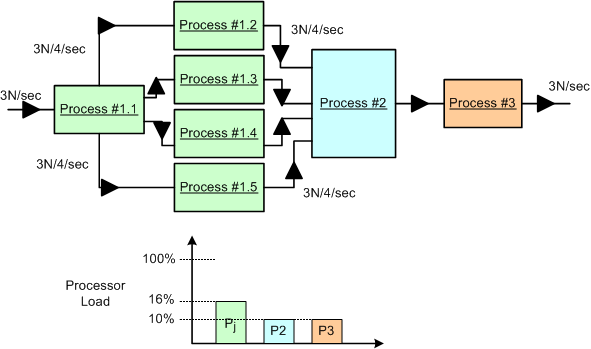

One approach is to dive into the algorithmic details of the P1 CPU hog and explore parallelization options for the beast. Assume that we are lucky and we discover that we are able to divide and conquer the P1 oinker into 5 equi-hungry sub-algorithms as shown below. In this case, assuming that we can allocate each process to its own CPU (multi-core or separate boxes), then we may be done solving the problem at the application layer. No?

Do you detect any major conceptual holes in this blarticle?