Archive

Don’t Be Evil

If you don’t know that Google’s informal corporate motto is “Don’t Be Evil“, then either you were born yesterday or you shouldn’t be reading this ridiculously inane blog – or both.

While reading Stephen Levy‘s well written, informative, and entertaining book, “In The Plex“, Mr. Levy tells the story of how the controversial and tough-to-live-up-to Google war cry came into existence. Here, he describes the first triggering event:

Mr. Levy goes on to say:

Note that 15 employees were assembled from across a broad swath of the company. Do you notice something amiss? Uh, how about the fact that the two founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page weren’t involved?

As the group debated the motto, here’s what one group member said:

Note that everyone had a chance to weigh in, and thus, “Don’t Be Evil” was internalized by the whole org. It wasn’t handed down from on high by a politburo or junta or God-like individual that “obviously knows what’s best for all the children in the borg“.

Did, or do, you have the chance to provide feedback on your corpo values or philosophy? Are they authentic like Google’s and Zappos.com’s, or are they a copy-and-paste job from a 1970’s vintage management book? If they’re a copy-and-paste job, have you suggested revisiting them? If so, how was your suggestion received?

Structure And Behavior

One of the principles of systems thinking is that structure facilitates or inhibits specific behaviors. For example, if we didn’t have hands (or, in some cases, neither hands or feet), we wouldn’t be able to write – the structure wouldn’t allow it. If we didn’t have vocal chords, we wouldn’t be able to speak – the structure wouldn’t allow it. If a car’s engine didn’t connect to the drive shaft, it wouldn’t be able to “transport” – the structure wouldn’t allow it. If a system didn’t have redundant elements, it wouldn’t be able to automatically recover from failures – the structure wouldn’t allow it.

The same holds true for organizational structures that group people together for a purpose. The org structure can be an enabler or inhibitor of the behaviors required to fulfill the purpose for which the group has been assembled. A mismatch between purpose and structure usually leads to failure at some unknown time in the future.

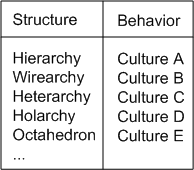

The table below lists several org structures concocted by BD00, including the ubiquitously pervasive and manager-revered “hierarchy“, along with the obscure, Fuller/Beer “octahedron“. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each structure?

Expertise And Position

In Seeing Your Company as a System, Andrea Gabor cites Weick and Sutcliffe’s book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty“:

Mindful organizations, they (Weick and Sutcliffe) explain, are characterized by a broadly defined “deference to expertise” in a setting where “expertise is not necessarily matched with hierarchical position.” Mindful organizations are also capable of seeing weak signals of systemic failure and responding with vigor. To support this capability, such organizations strive for open communication, recognizing that if people refuse to speak up out of fear, this capability will be undermined.

In unmindful orgs (“unmindful” is the politically correct way of referring to CLORGs and DYSCOs), most people in the borg are conditioned to auto-think that expertise equates to hierarchical position. Thus, the infallibles in the upper layers, while espousing otherwise, don’t strive for open communication and they ignore both weak and strong negative feedback signals from the DICs in the lower, less “expert” layers. To add insult to injury, since the DICsters down in the boiler room are conditioned to auto-think the same expertise-position relationship, they don’t “speak up” out of fear of looking, or being told that they are, stupid. Bummer.

Process, Passion, And Quality

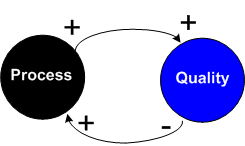

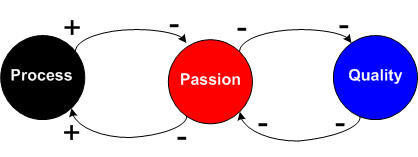

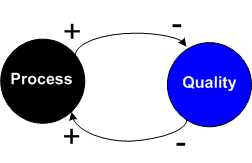

Naive managers (usually those who get drunk on large quantities of 6-sigma, CMMI, ISO-90XX, EVM, and/or PMP kool aid) tend to think of the correlation between process and quality like this:

This cause-effect diagram can be read as “more process imposition leads to more quality; less quality leads to more process imposition“. What’s missing in this simplistic diagram? Could it be something that represents the human element?

This cause-effect diagram can be read as “more process imposition leads to more quality; less quality leads to more process imposition“. What’s missing in this simplistic diagram? Could it be something that represents the human element?

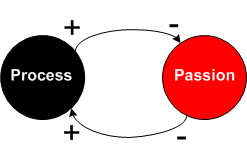

In the blarticle, “Process kills developer passion“, James Turner writes about the human element of “passion“:

…passionate programmers write great code, but process kills passion. Disaffected programmers write poor code, and poor code makes management add more process in an attempt to “make” their programmers write good code. That just makes morale worse, and so on.

If you believe Mr. Turner, then the cause-effect diagram for process and passion is a self-reinforcing loop that may snuff out passion over time:

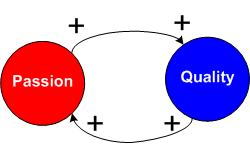

So, what about the relationship between passion and quality? I think that many would agree that it is thus:

So, what about the relationship between passion and quality? I think that many would agree that it is thus:

When we integrate the two models above, we get….

When we integrate the two models above, we get….

Moving from left to right, and then from right to left we read that:

Moving from left to right, and then from right to left we read that:

an increase in process triggers a decrease in passion, which triggers a decrease in quality, which triggers a further decrease in passion, which triggers an increase in process imposition. Round and round we go.

If we assume that “passion” is an integral player in the system, but hide it in the above diagram to simulate a common managerial blindspot, the end to end process-quality cause-effect diagram emerges as:

If we compare this derived result to the first naive manager mental model which doesn’t include the messy “passion” element, what’s the difference?

If we compare this derived result to the first naive manager mental model which doesn’t include the messy “passion” element, what’s the difference?

What’s On Your List?

In Russell Ackoff‘s “Idealized Design” method, he suggests that designers assume that the system they’re trying to improve/re-design exploded last night and it no longer exists. D’oh! He does this in order to put a jackhammer to the layers of unquestioned, un-noticed, outdated, and hard-wired assumptions that reside in every designer’s mind.

So, if you were part of an emergency task force charged with re-designing your no-longer-existing org, what candidate list of ideas would you concoct? To help jumpstart your underused, but innately powerful creative talents, here’s an outrageous example list that I stole from a raging lunatic:

- Provide two computer monitors for every employee and religiously refresh workstations every three years.

- Provide two projectors and multiple whiteboards in each conference room. Ensure a plentiful supply of working markers. No exclusive executive conference rooms – all rooms equally accessible to all, with negotiated overrides.

- Physically co-locate all product and project teams for the duration. Disallow a rotating door where projectees can come and go as they please or management pleases – with rare exceptions of course.

- Put round tables in every conference room.

- Distribute executive and middle manager offices throughout the org. No bunching in a cloistered, elitist corner, space, or glistening building with HR/Marketing/PR/finance/contracts or other overhead functions.

- Require every manager in the org with direct reports to periodically ask each direct report: “How can I help you do your job better?” at frequent one-on-one meetings. If a manager has too many direct reports – then fix it somehow.

- Require every manager who has managers reporting to him/her to ask each of his/her subordinate managers: “Can you give me an example of how you helped one or more of your direct reports to grow and develop this year?“.

- Require periodic, skip-level manager-subordinate meetings where the manager triggers the conversation and then just listens.

- If “schedule is king” all the time, then write it into your prioritized core values list – just above “engineering excellence and elegant products“. If your core values list contains conflicting values, then prioritize it.

- Carefully and continuously monitor group (not individual) interaction protocols and behaviors. Diligently prevent protocol bloat and convert tightly coupled, synchronous client-server relationships into loosely couple, asynchronous, peer-to-peer exchanges.

- Explicitly budget X days of user-chosen training to every person in the org and enforce the policy’s execution.

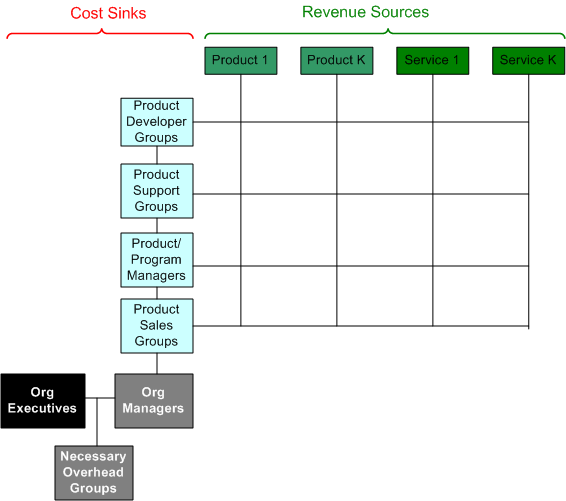

- To reinforce why the org exists and de-emphasize who is “more important” than who, publish a product and/or service-centric org chart with products/services across the top and groups, including all managers, down the side. Preferably, the managers should be on the bottom propping up the org. (See figure below).

- Abandon the “employee-in-a-box” classification and reward system. Pay each person enough so that pay isn’t an issue, and publicly publish all salaries as a self-regulating mechanism.

- Create policy making and problem solving councils up and down the org. Members must consist of three levels of titles and include both affectees in addition to effectors.

- Give leadees a say regarding who their leaders are. Publicly publish all reviews of leaders by leadees.

- Require periodic job rotations to reduce the org’s truck number.

- Frequently survey the entire org for ideas and problem hot spots. Visibly act on at least concern within a relatively short amount of time after each survey.

- Provide every employee with an org credit card and budget a fixed amount of money where no approvals are required for purchases. Fix the purchasing system to make it ridiculously easy for expenses to be submitted.

Centralized, Federated, Decentralized

1 Prelude

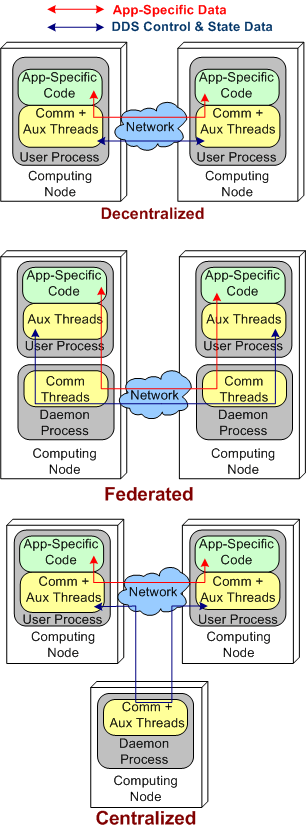

A colleague on LinkedIn.com pointed me toward this Doug Schmidt, et al, paper: “Evaluating Technologies for Tactical Information Management in Net-Centric Systems“. In it, Doug and crew qualitatively (scalability, availability, configurability) and quantitatively (latency, jitter) evaluate three different architectural implementations of the Object Management Group‘s (OMG) Data Distribution Service (DDS): centralized, federated, and decentralized.

The stacked trio of figures below model the three DDS architecture types. They’re slightly enhanced renderings of the sketches in the paper.

2 Quantitative Comparisons

DDS was specifically designed to meet the demanding latency and jitter (the standard deviation of latency) performance attributes that are characteristic of streaming, Distributed Real-Time Event (DRE) systems like defense and air traffic control radars. Unlike most client-server, request-response systems, if data required for human or computer decision-making is not made available in a timely fashion, people could die. It’s as simple and potentially horrible as that.

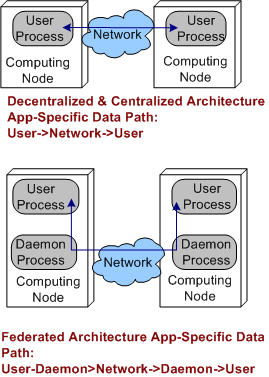

Applying the systems thinking idiom of “purposeful, selective ignorance“, the pics below abstract away the unimportant details of the pics above so that the architecture types can be compared in terms of latency and jitter performance.

By inspecting the figures, it’s a no brainer, right? The steady-state latency and jitter performance of the decentralized and centralized architectures should exceed that of the federated architecture. There is no “middleman“, a daemon, for application layer data messages to pass through.

Sure enough, on their two node test fixture (I don’t know why they even bothered with the one node fixture since that really isn’t a “distributed” system in my mind) , the Schmidt et al measurements indicate that the latency/jitter performance of the decentralized and centralized architectures exceed that of the federated architecture. The performance difference that they measured was on the order of 2X.

3 Qualitative Comparisons

In all distributed systems, both DRE and Client-Server types, achieving high operational availability is a huge challenge. Hell, when the system goes bust, fuggedaboud the timeliness of the data, no freakin’ work can get done and panic can and usually does set in. D’oh!

With that scary aspect in mind, let’s look at each of the three architectures in terms of their ability to withstand faults.

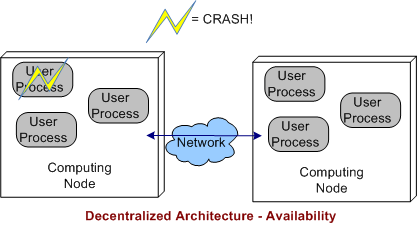

3.1 Decentralized Architecture Availability

In a decentralized architecture, there are no invasive daemons that “leak” into the application plane so we can’t talk about daemon crashes. Thus, right off the bat we can “arguably” say that a decentralized architecture is more resistant to faults than the federated or centralized architectures.

As the picture below shows, when a user application layer process dies, the others can continue to communicate with each other. Depending on what the specific application is required to do during operation, at least some work may be able to still get accomplished even though one or more app components go kaput.

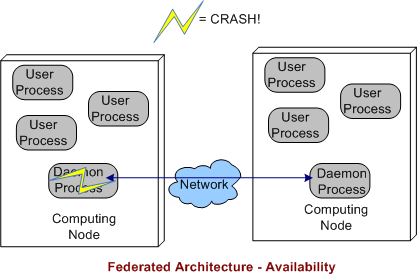

3.2 Federated Architecture Availability

In a federated architecture, when a daemon process dies, a whole node and all the subscriber application user processes running on it are severed from communicating with the user processes running on the other nodes (see the sketch below) in the system. Thus, the federated architecture is “arguably” less fault tolerant than the decentralized and (as we’ll see) centralized architectures. However, through judicious “allocation” of user processes to nodes (the fewer the better – which sort of defeats the purpose of choosing a federation for per node intra-communication performance optimization), some work still may be able to get accomplished when a node’s daemon crashes.

If the node daemons stay viable but a user application dies, then the behavior of a federated architecture, DDS-based system is the same as that of a decentralized architecture

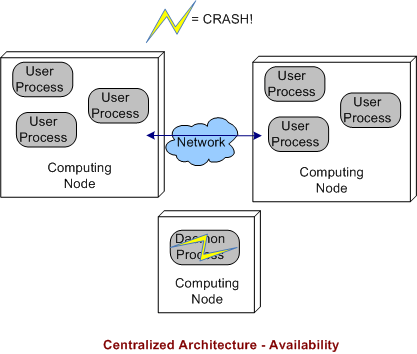

3.3 Centralized Architecture Availability

Finally, we come to the robustness of a centralized DDS architecture. As shown below, since the single daemon overlord in the system is not (or should not be) involved in inter-process application layer data communications, if it crashes, then the system can continue to do its full workload. When a user process crashes instead of, or in addition to, the daemon, then the system’s behavior is the same as a decentralized architecture.

4 BD00 Commentary

Because he works on data streaming DRE radar systems, Jimmy likes, I mean BD00 likes, the DDS pub-sub architectural style over broker-based, distributed communication technologies like C/S CORBA and JMS queues. It should be obvious that the latter technologies are not a good match for high availability and low latency DRE applications. Thus, trying to jam fit a new DRE application into a CORBA or JMS communication platform “just because we have one” is a dumb-ass thing to do and is sure to lead to high downstream maintenance costs and a quicker route to archeosclerosis.

Within the DDS space, BD00 prefers the decentralized architecture over the federated and centralized styles because of the semi-objective conclusions arrived at and documented in this post.

Seven Unsurprising Findings

In the National Acadamies Press’s “Summary of a Workshop for Software-Intensive Systems and Uncertainty at Scale“, the Committee on Advancing Software-Intensive Systems Producibility lists 7 findings from a review of 40 DoD programs.

- Software requirements are not well defined, traceable, and testable.

- Immature architectures; integration of commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) products; interoperability; and obsolescence (the need to refresh electronics and hardware).

- Software development processes that are not institutionalized, have missing or incomplete planning documents, and inconsistent reuse strategies.

- Software testing and evaluation that lacks rigor and breadth.

- Lack of realism in compressed or overlapping schedules.

- Lessons learned are not incorporated into successive builds—they are not cumulative.

- Software risks and metrics are not well defined or well managed.

Well gee, do ya think they missed anything? What I’d like to know is what, if anything, they found right with those 40 programs. Anything? Maybe that would help more than ragging on the same issues that have been ragged on for 40 years.

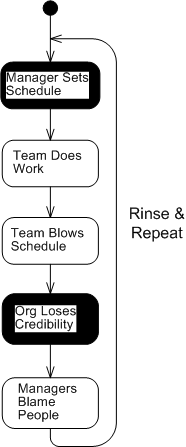

My fave is number five (with number 1 a close second). When schedules concocted by non-technical managers without any historical backing or input from the people who will be doing the work are publicly promised to customers, how can anyone in their right mind assert that they’re “realistic“? The funny thing is, it happens all the time with nary a blink – until the fit hits the shan, of course. D’oh!

Meeting schedules based on historically tracked data and input from team members is challenging enough, but casting an unsubstantiated schedule in stone without an explicit policy of periodically reassessing it on the basis of newly acquired knowledge and learning as a project progresses is pure insanity. Same old, same old.

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by. – Douglas Adams

Would YOU Join My Group?

I’m recently toyed with the idea of starting a LinkedIn.com group named “Frontal Assault Idiots“. This would be the group’s logo:

Alas, I rejected the idea because the only members who would join are me & my buddy, Chetan Dhruve – and no one would post any discussions. D’oh!

Using The New C++ DDS API

PrismTech‘s Angelo Corsaro is a passionate and tireless promoter of the OMG’s Data Distribution Service (DDS) distributed system communication middleware technology. (IMHO, the real power of DDS over other messaging services and messaging-based languages like Erlang (which I love) is the rich set of Quality of Service (QoS) settings it supports). In his terrific “The Present and Future of DDS” pitch, Angelo introduces the new, more streamlined, C++ and Java DDS APIs.

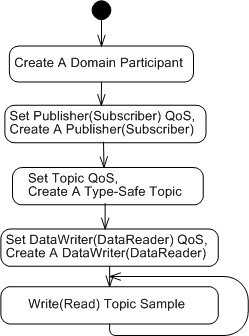

The UML activity diagram below illustrates the steps for setting up and sending (receiving) topic samples over DDS: define a domain; create a domain participant; create a QoS configured, domain-resident publisher (or subscriber); create a QoS configured and type-safe topic; create a QoS configured, publisher-resident, and topic-specific dataWriter; and then go!

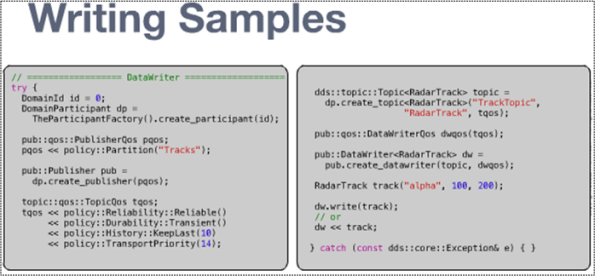

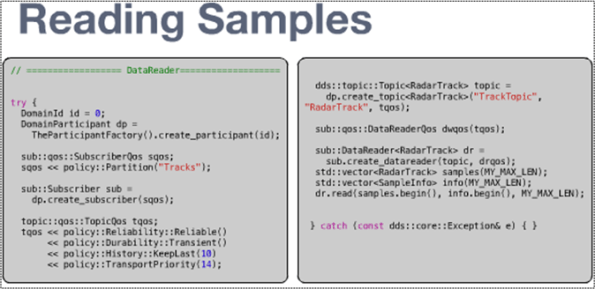

Concrete C++ implementations of the activity diagram, snipped from Angelo’s presentation, are presented below. Note the incorporation of overloaded insertion operators and class templates in the new API. Relatively short and sweet, no?

Even though the sample code shows non-blocking, synchronous send/receive usage, DDS, like any other communication service worth its salt, provides API support for blocked synchronous and asynchronous notification usage.

So, what are you waiting for? Skidaddle over to PrismTech’s OpenSplice DDS page, download the community edition libraries for your platform, and start experimenting!

Rare Sighting

A friend and colleague sent me this terrific link: “The Wall Says It’s Time To Go“. He asked me for my highly esteemed, expert opinion on the manager described in the “You’re On Your Own” story. I told him that the manager’s behavior was a great example of the rarely-seen-in-nature, PHOR species. Here are a coupla snippets from which I formulated my unassailable opinion:

While his staff worked away, he sat with his feet resting on his desk reading the newspaper. The only time he got up was when an employee came in to ask for help. Then the manager dropped his paper and embraced whatever problem the employee was grappling with.

…a manager’s job is to be a mentor, and although the manager spends most of the day with his feet up, his role is more important than any work being done in the office. His job is to enable his employees to take whatever steps are necessary to ensure their continuing value to the company.

OK, so there’s no context for this example – we don’t know what the nature of the work is, or what products/services the enterprise creates and delivers. Nevertheless, in any setting, I’d prefer to have managers sit around doing mostly nothing until they’re needed instead of jetting around to one useless half-hour meeting after another feigning business and importance. But that’s me, and maybe only me. What about you?