Archive

Unavailability II

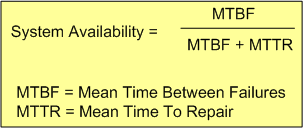

The availability of a software-intensive, electro-mechanical system can be expressed in equation form as:

With the complexity of modern day (and future) systems growing exponentially, calculating and measuring the MTBF of an aggregate of hardware and (especially) software components is virtually impossible.

Theoretically, the MTBF for an aggregate of hardware parts can be predicted if the MTBF of each individual part and how the parts are wired together, are “known“. However, the derivation becomes untenable as the number of parts skyrockets. On the software side, it’s patently impossible to predict, via mathematical derivation, the MTBF of each “part“. Who knows how many bugs are ready to rear their fugly heads during runtime?

From the availability equation, it can be seen that as MTTR goes to zero, system availability goes to 100%. Thus, minimizing the MTTR, which can be measured relatively easily compared to the MTBF ogre, is one effective strategy for increasing system availability.

The “Time To Repair” is simply equal to the “Time To Detect A Failure” + “The Time To Recover From The Failure“. But to detect a failure, some sort of “smart” monitoring device (with its own MTBF value) must be added to the system – increasing the system’s complexity further. By smart, I mean that it has to have built-in knowledge of what all the system-specific failure states are. It also has to continually sample system internals and externals in order to evaluate whether the system has entered one of those failures states. Lastly, upon detection of a failure, it has to either inform an external agent (like a human being) of the failure, or somehow automatically repair the failure itself by quickly switching in a “good” redundant part(s) for the failed part(s). Piece of cake, no?

Unavailable For Business

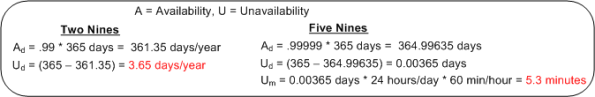

The availability of a system is usually specified in terms of the “number of nines” it provides. For example, a system with an availability specification of 99.99 provides “two nines” of availability. As the figure below shows, a service that is required to provide five nines of availability can only be unavailable 5.3 minutes per year!

Like most of the “ilities” attributes, the availability of any non-trivial system composed of thousands of different hardware and software components is notoriously difficult and expensive to predict or verify before the system is placed into operation. Thus, systems are deployed and fingers crossed in the hope that the availability it provides meets the specification. D’oh!

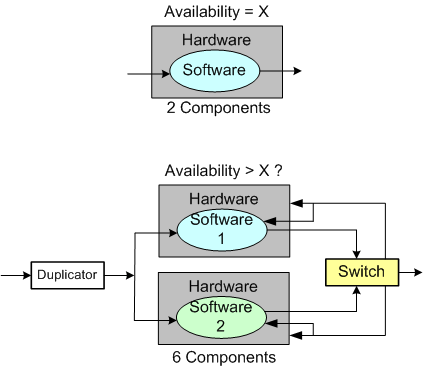

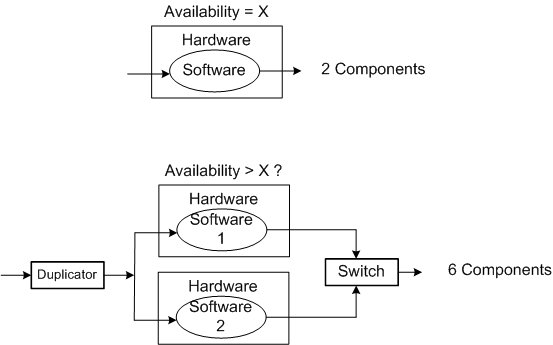

One way of supposedly increasing the availability of a system is to add redundancy to its design (see the figure below). But redundancy adds more complex parts and behavior to an already complex system. The hope is that the increase in the system’s unavailability and cost and development time caused by the addition of redundant components is offset by the overall availability of the system. Redundancy is expensive.

As you might surmise, the switch in the redundant system above must be “smart“. During operation, it must continuously monitor the health of both output channels and automatically switch outputs when it detects a failure in the currently active channel.

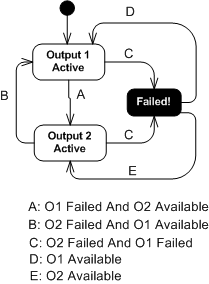

The state transition diagram below models the behavior required of the smart switch. When a switchover occurs due to a detected failure in the active channel, the system may become temporarily unavailable unless the redundant subsystem is operating as a hot standby (vs. cold standby where output is unavailable until it’s booted up from scratch). But operating the redundant channel as a hot standby stresses its parts and decreases overall system availability compared to the cold spare approach. D’oh!

Another big issue with adding redundancy to increase system availability is, of course, the BBoM software. If the BBoM running in the redundant channel is an exact copy of the active channel’s software and the failure is due to a software design or implementation defect (divide by zero, rogue memory reference, logical error, etc), that defect is present in both channels. Thus, when the switch dutifully does its job and switches over to the backup channel, it’s output may be hosed too. Double D’oh! To ameliorate the problem, a “software 2” component can be developed by an independent team to decrease the probability that the same defect is inserted at the same place. Talk about expensive?

Achieving availability goals is both expensive and difficult. As systems become more complex and human dependence on their services increases, designing, testing, and delivering highly available systems is becoming more and more important. As the demand for high availability continues to ooze into mainstream applications, those orgs that have a proven track record and deep expertise in delivering highly available systems will own a huge competitive advantage over those that don’t.