Archive

Learn A Little, Do A Lot

There is no “learn” in “do” – manager yoda

Assume that you have a basic skill set, some expertise, and some experience in a domain where a task needs to be performed to solve a problem. Now assume that your boss assigns that problem to you and, out of curiosity you decide to track how you go about solving the problem.

The figure below shows the likely result of tracking your problem solving effort. You probably converged on the solution via a series of continuous Learning-Doing iterations. On your first iteration, you gathered a bunch of information and spent a considerable amount of time immersing yourself in the problem area to “learn” both context and content. Then you “did” a little, producing some type of work output – which was wrong. Next, you spent some more time “learning” by analyzing your output for errors/mistakes and correlating your work against the information pile that you amassed. Then you repeated the cycle, doing more while having to learn less on each subsequent iteration until voila, the problem was solved!

So, how can this natural problem solving process get hosed and low quality, shoddy work outputs be produced? Here are three possible reasons:

- Lack of availability of, or accessibility to, applicable information.

- Low quality, inconsistent, and ambiguous information about the problem.

- Explicit or implicit pressure to abandon the natural and iterative Learn-then-Do problem solving process.

IMHO, it should be a manager’s top priority to remove these obstacles to success. If a manager ignores, or can’t fulfill, this critical responsibility and he/she is just an obsessive, textbook-trained “status taker and schedule jockey”, then his/her team will transform into a group of low quality performers. More importantly, he/she will lose the respect of those team members who deeply care about quality.

Accountability

Everybody loves to talk about “holding people accountable!”. You know, in the sense of “Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia“. The dilemma is that lots of people want to hold others accountable without being held accountable themselves. Management wants to hold the workforce accountable, but not vice-versa. The DICforce wants to hold management accountable, but not vice-versa.

When managers clearly define, specify, and communicate expected employee outputs along with the times that those outputs are due, then they have the information to hold an employee “accountable” if those requirements are not met. However, bad managers (of which there are many) aren’t competent enough to know how to clearly define, specify, and communicate what specifically is needed to get the job done. They do, however, know how to specify and monitor due dates – because it doesn’t require much brain matter to do so. Any wino off the street could be hired to dictate and watch unrealistic due dates.

On the other side of the fence, since bad managers don’t contribute anything to the org other than “status taking and schedule jockeying“, employees have no reliable and honest way of holding managers accountable (even if they were “allowed” to; which they aren’t). What’s an employee supposed to do? Call out a manager for not “taking status and watching schedule“? Yeah, right.

Sooooooo. Once you become a manager, a rare good one or a ubiquitous bad one, you’ve got it made. Your buddies who anointed you into the management guild won’t hold you accountable because it’ll make them look bad for choosing you (and of course, they can’t look bad in front of the troops because they have to maintain the illusion of infallibility). Your employees won’t hold you accountable either, because they want to remain hassle-free and you most likely don’t contribute anything of substance that is publicly and scrutably visible. It’s the best of both worlds and, in management lingo, a “win-win” situation.

Directagers

Director of communications, director of operations, director of engineering, director of marketing, director of strategy. Yada, yada, yada. Everyone is, or wants to become, a “Director” of something. The ultimate directorship, of course, is to be elected to sit on one or more cushy Boards Of “Directors”.

Not discounting the title of “Chief”, the title of “Director” seems to have overtaken “Manager” as the coveted corpo title dujour. Compared to an honorable and esteemed “Director”, a “Manager” is now almost as unimportant as an “associate”, or equivalently, an “in-duh-vidual contributor” (gasp!). The title of “Manager” is……. so yesterday.

So what’s the next title to be inserted into the divisive corpo caste system, the “Directager“? Come on, take a guess.

Three Things

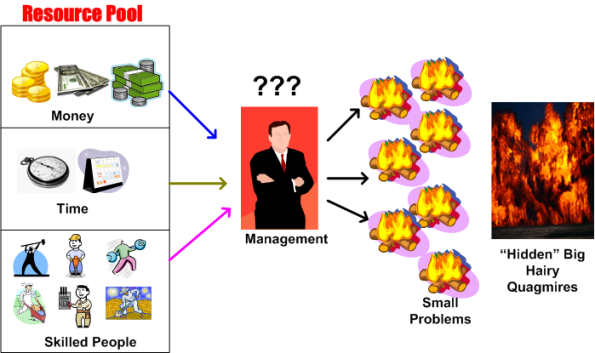

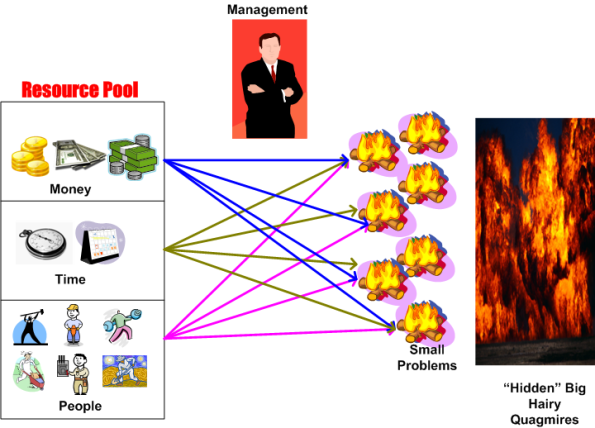

Three things: people, money, and time. These three interdependent resource types are the weapons that managers can deploy to create and sustain wealth for an organization. Managers are tasked with the challenge of judiciously apportioning these raw resources to the creation and sustainment of value-added products and services that solve customer problems. In addition to the creation and sustainment of products and services, the difficulty of continuously aligning and steering large groups of people toward the goals of growth and increasing profitability causes problem “fires” to be ignited within the corpo citadel. Bloated processes and warring factions are just two examples of the infinite variety of “pop up” fires that impede growth and profitability.

Left unchecked, internal brush fires always grow and merge into paradoxically massive, but hidden, forest fires that consume valuable resources. Brush fires feed on neglect and ignorance. Instead of creating wealth and continuously satisfying the external customer base, the three resource pools get exhausted by constantly being allocated to extinguishing internal fires.

Unless managers can “see” the growing fires, one or more massive fireballs can burn the organization to the ground. So, how can managers prevent massive fireballs from consuming would-be profits and customer goodwill? By constantly listening to, and investigating, and smartly acting on, the concerns of their people and their customers. Just listening is not enough. Just investigating is not enough. Just listening and investigating is not enough. Just listening and investigating and ineffective action is not enough. Listening, investigating, and effective action are all required.

Analysis Paralysis Vs. 59 Minutes

“If I had an hour to save the world, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute finding solutions” – Albert Einstein

If they didn’t know that Einstein said the quote above, MBA taught and metrics-obsessed “go-go-go” textbook managers would propose that the person who did say it was a slacker who suffered from “analysis paralysis”. In the Nike age of “just do it” and a culture of “act first and think later” (in order to show immediate progress regardless of downstream consequences), not following Einstein’s sage advice often leads to massive financial or human damage when applied to big, multi-variable hairball problems.

The choice between “act first, think later” (AFTL) and “think first, act later” (TFAL) is not so simple. For small, one dimensional problems where after-the-fact mistakes can be detected quickly and readjustments can be made equally as quickly, AFTL is the best way to go. However, most managers, because they are measured on schedule and cost performance and not on quality (which is notoriously difficult to articulate and quantify), apply the AFTL approach exclusively. They behave this way regardless if the situation cries out for TFAL because that’s the way that hierarchical structured corpo orgs work. Since the long term downstream effects of crappy decisions may not be traceable back to the manager who made them, and he/she will likely be gone when the damage is discovered, everybody else loses – except the manager, of course. Leaders TFAL and managers AFTL.

Sassy!

The SAS Institute has been one of my favorite software companies to watch over the years. They were like Google before Google. The reason that I’m mentioning SAS is because while I was browsing through my notes, I stumbled upon this quote from a SAS manager:

Nothing corrodes respect between a boss and an employee more quickly than the sense that the boss has no idea what the employee is doing. Managers who understand the work that they oversee can make sure that details don’t slide. At SAS, groups agree on deadlines, and managers understand what their groups do — so unrealistically optimistic promises about time-tables and completion dates are relatively rare.

The quote came from this 2004 article in Fast Company magazine: Sanity Inc. The quote struck a chord with me back then, and it still does now. In my case, I don’t necessarily disrespect a manager that doesn’t know what I’m doing. I disrespect managers who:

- Are apathetic and show no interest in what I’m doing, regardless of whether they know the subject matter or not.

- Don’t ask me how I’m doing, and how they can help me do my job better, regardless of whether they know the subject matter or not.

- Just stop by only when they need to collect status, without wanting to hear about any bureaucratic procedural roadblocks that are, or specific people who are, hindering my progress.

- Pretend to know what I’m doing and make suggestions on what to do next, even though we both know (or, at least I know) that the manager has no clue.

How about you? What causes you to lose respect for your manager(s)?

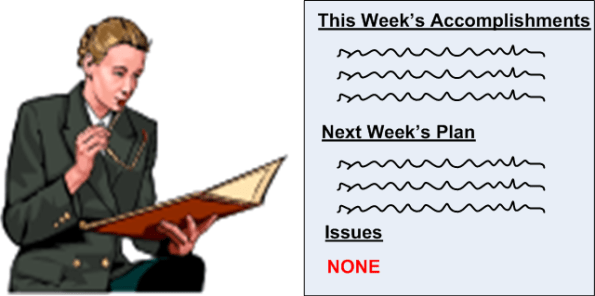

No Issues Please!

One of the differences between a leader and a manager is the way that they handle status reports from team members. When a leader receives a status report from a team member, she zeros in on the issues/roadblocks section and gets immediately to work. She talks to the team member to ferret out the problem specifics. For those issues that are out of the control of the team member, the leader becomes proactive and goes out and resolves the problem. It’s that simple.

What does a manager do with an issue? A manager ignores it. Hell, it’s work and thus, it’s outside the scope of her responsibility. After a few weeks of submitting issues and seeing no action taken, team members flip the bozo bit on the manager. Trust and respect, which are hard to earn but easy to lose, go right out the window.

Leaders rule, managers drool.