Archive

Prune Me, Please

In “Integrating CMMI and Agile Development“, Paul E. McMahon asserts that even though they’d like to, many orgs don’t “prune” their fatty, inefficient, and costly processes because:

..it requires a commitment of the time of key people in the organization who really use the processes. Usually these people are just too busy with direct contract work and the priority doesn’t allow this to happen.

One of BD00’s heroes, the Oracle of Omaha, has a different take on it:

There seems to be some perverse human characteristic that likes to make easy things difficult. – Warren Buffet

Of course, both reasons could apply.

Four Reasons

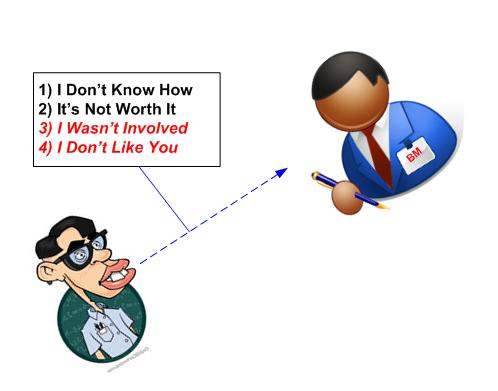

When I don’t do something that I’m “supposed” to do, it comes down to one of two reasons:

- I don’t know how to do it because of a lack of expertise/experience (ability).

- I don’t believe it adds any, or enough, value (motivation).

But wait, I lied! There are also two more potential, but publicly undiscussable reasons. They’re elegantly put into words by Mr. Alexander Hamilton:

Men often oppose a thing merely because they have had no agency in planning it, or because it may have been planned by those whom they dislike. – Alexander Hamilton

How about you? When you don’t do something expected of you, why don’t you do it?

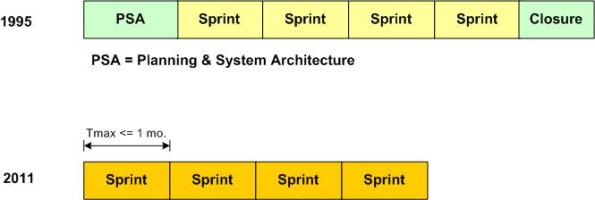

Bring Back The Old

The figure below shows the phases of Scrum as defined in 1995 (“Scrum Development Process“) and 2011 (The 2011 Scrum Guide). By truncating the waterfall-like endpoints, especially the PSA segment, the development framework became less prescriptive with regard to the front and back ends of a new product development effort. Taken literally, there are no front or back ends in Scrum.

The well known Scrum Sprint-Sprint-Sprint-Sprint… work sequence is terrific for maintenance projects where the software architecture and development/build/test infrastructure is already established and “in-place“. However, for brand new developments where costly-to-change upfront architecture and infrastructure decisions must be made before starting to Sprint toward “done” product increments, Scrum no longer provides guidance. Scrum is mum!

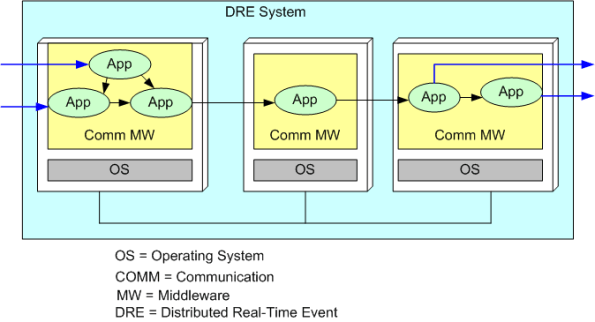

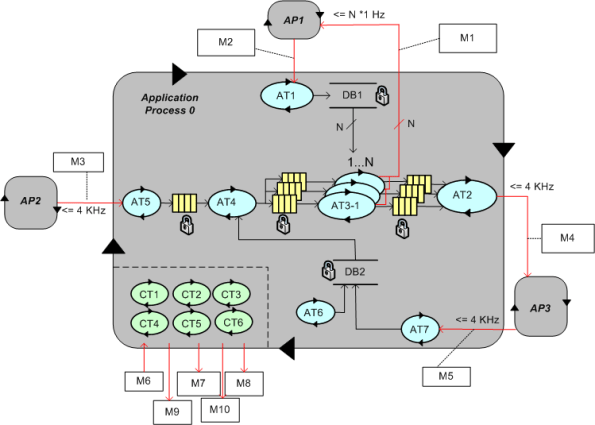

The figure below shows a generic DRE system where raw “samples” continuously stream in from the left and value-added info streams out from the right. In order to minimize the downstream disaster of “we built the system but we discovered that the freakin’ architecture fails the latency and/or thruput tests!“, a bunch of critical “non-functional” decisions and must be made and prototyped/tested before developing and integrating App tier components into a potentially releasable product increment.

I think that the PSA segment in the original definition of Scrum may have been intended to mitigate the downstream “we’re vucked” surprise. Maybe it’s just me, but I think it’s too bad that it was jettisoned from the framework.

The time’s gone, the money’s gone, and the damn thing don’t work!

Humbled And Overjoyed

I’m humbled and overjoyed that some people actually appreciate and want to hear what BD00 has to say:

If you don’t overcome the fear of publicly expressing yourself somehow, then how else can you experience the same warm feelings – outside of your small, bounded, circle of family and friends? Why, daily, at work, of course.

From Complexity To Simplicity

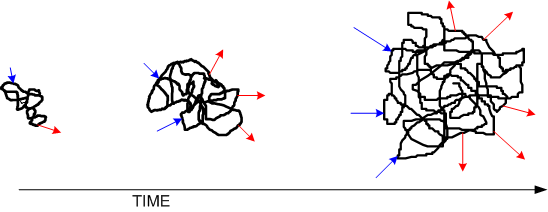

As the graphic below shows, when a system evolves, it tends to accrue more complexity – especially man-made systems. Thus, I was surprised to discover that the Scrum product development framework seems to have evolved in the opposite direction over time – from complexity toward simplicity.

The 1995 Ken Schwaber “Scrum Development Process“ paper describes Scrum as:

The 1995 Ken Schwaber “Scrum Development Process“ paper describes Scrum as:

Scrum is a management, enhancement, and maintenance methodology for an existing system or production prototype.

However, The 2011 Scrum Guide introduces Scrum as:

Scrum is a framework for developing and sustaining complex products.

Thus, according to its founding fathers, Scrum has transformed from a “methodology” into a “framework“.

Even though most people would probably agree that the term “framework” connotes more generality than the term “methodology“, it’s arguable whether a framework is simpler than a methodology. Nevertheless, as the figure below shows, I think that this is indeed the case for Scrum.

In 1995, Scrum was defined as having two bookend, waterfall-like, events: PSA and Closure. As you can see, the 2011 definition does not include these bookends. For good or bad, Scrum has become simpler by shedding its junk in the trunk, no?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that is not there; because it isn’t needed. (Middle management?)

I think, but am not sure, that the PSA event was truncated from the Scrum definition in order to discourage inefficient BDUF (Big Design Up Front) from dominating a project. I also think, but am not sure, that the Closure event was jettisoned from Scrum to dispel the myth that there is a “100% done” time-point for the class of product developments Scrum targets. What do you think?

Related articles

- Scrum Cheat Sheet (bulldozer00.com)

- Ultimately And Unsurprisingly (bulldozer00.com)

- Introduction to scrum (slideshare.net)

- Scrum Master, a management position? (scrumguru.wordpress.com)

- Developing, and succeeding, with Scrum (techworld.com.au)

Software Reuse

As a follow up to my last post, I decided to post this collection of quotes on software reuse from some industry luminaries:

Planned? Top-down? Upfront? In this age of “agile“, these words border on blasphemy.

The Odds May Not Be Ever In Your Favor

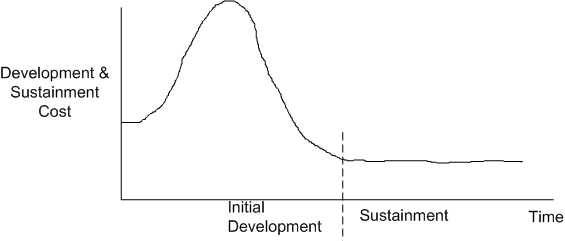

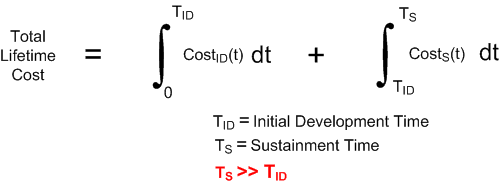

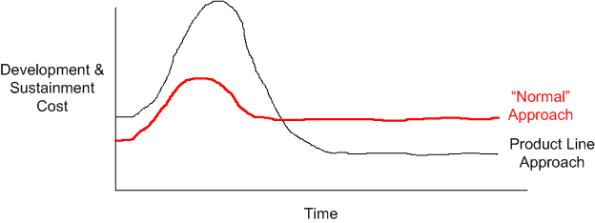

The sketch below models a BD00 concocted reference cost curve for a single, one-off, software-intensive product. Note that since the vast majority of the accumulated cost (up to 3/4 of it according to some experts) of a long-lived product is incurred during the sustainment epoch of a product’s lifetime, the graph is not drawn to scale.

If you’re in the business of providing quasi-similar, long-lived, software-intensive products in a niche domain, one strategy for keeping sustainment costs low is to institutionalize a Software Product Line Approach (SPLA) to product development.

A software Product Line is a set of software-intensive systems that share a common, managed set of features satisfying the specific needs of a particular market segment or mission and that are developed from a common set of core assets in a prescribed way. – Software Engineering Institute

As the diagram below shows, the idea behind the SPLA is to minimize the Total Lifetime Cost by incurring higher short-term costs in order to incur lower long-term costs. Once the Product Line infrastructure is developed and placed into operation, instantiating individual members of the family is much less costly and time consuming than developing a one-off implementation for each new application and/or customer.

Some companies think themselves into a false sense of efficiency by fancying that they’re employing an SPLA when they’re actually repeatedly reinventing the wheel via one-off, copy-and-paste engineering.

You can’t copy and paste your way to success – Unknown

If your engineers aren’t trained in SPLA engineering and you’re not using the the terminology of SPLA (domain scoping, core assets, common functionality, variability points, etc) in your daily conversations, then the odds may not be ever in your favor for reaping the benefits of an SPLA.

Related articles

- Out Of One, Many (bulldozer00.com)

- Product Line Blueprint (bulldozer00.com)

Beginner, Intermediate, Expert

Check out this insightful quote from Couchbase CTO Damien Katz:

Threads are hard because, despite being extremely careful, it’s ridiculously easy to code in hard to find, undeterministic, data races and/or deadlocks. That’s why I always model my multi-threaded programs (using the MML, of course) to some extent before I dive into code:

Note that even though I created and evolved (using paygo, of course) the above, one page “agile model” for a program I wrote, I still ended up with an infrequently occurring data race that took months, yes months, to freakin’ find. The culprit ended up being a data race on the (supposedly) thread-safe DB2 data structure accessed by the AT4, AT6, and AT7 threads. D’oh!

Don’t Do This!

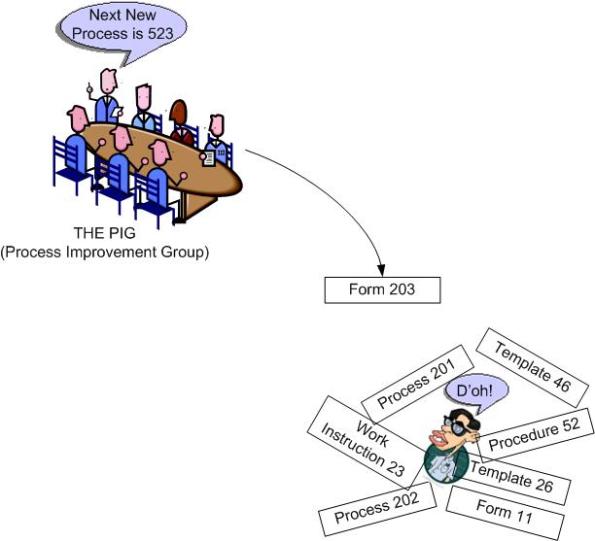

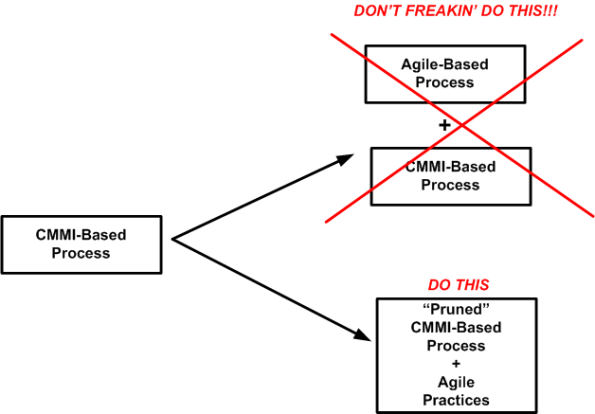

Because of its oxymoronic title, I started reading Paul McMahon’s “Integrating CMMI and Agile Development: Case Studies and Proven Techniques for Faster Performance Improvement“. For CMMI compliant orgs (Level >= 3) that wish to operate with more agility, Paul warns about the “pile it on” syndrome:

So, you say “No org in their right mind would ever do that“. In response, BD00 sez “Orgs don’t have minds“.

Ultimately And Unsurprisingly

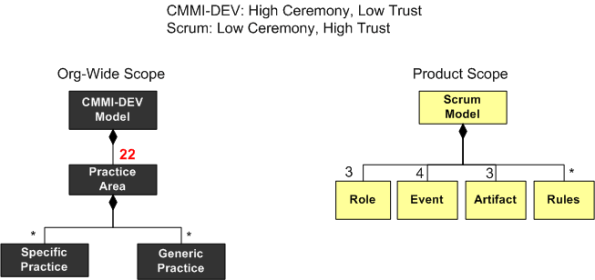

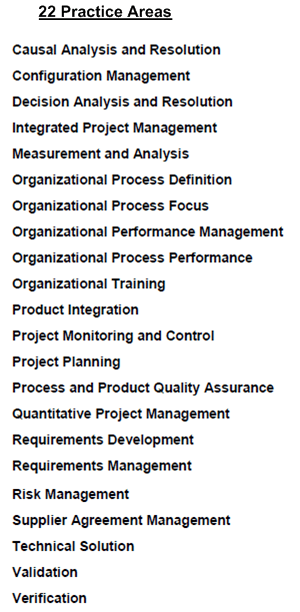

Take a look at the latest, dorky, BD00 diagram below. The process model on the left is derived from the meaty, 482 page CMMI-DEV SEI Technical Report. The model on the right is derived from the lean, 16 page Scrum Guide.

Comparing CMMI-DEV and Scrum may seem like comparing apples to oranges, but it’s my blog and I can write (almost) whatever I want on it, no?

Don’t write what you know, write what you want to know – Jerry Weinberg

The overarching purpose of both process frameworks is to help orgs develop and sustain complex products. As you can deduce, the two approaches for achieving that purpose appear to be radically different.

The CMMI-DEV model is comprised of 22 practice areas, each of which has a number of specific and generic practices. Goodly or badly, note that the word “practice” dominates the CMMI-DEV model.

Unlike the “practice” dominated CMMI-DEV model, the Scrum model elements are diverse. Scrum’s first class citizens are roles (people!), events, artifacts, and the rules of the game that integrate these elements into a coherent socio-technical system. In Scrum, as long as the rules of the game are satisfied, no practice is off limits for inclusion into the framework. However, the genius inclusion of time limits for each of Scrum’s 4 event types implicitly discourages heavyweight practices from being adopted by Scrum implementers and practitioners.

Of course, following either model or some hybrid combo can lead to product quality/time/budget success or failure. Aficionados on both sides of the fence publicly tout their successes and either downplay their failures (“they didn’t understand or really follow the process!“) or they ignore them outright. As everyone knows, there are just too many freakin’ metaphysical factors involved in a complex product development effort. Ultimately and unsurprisingly, success or failure comes down to the quality of the people participating in the game – and a lot of luck. Yawn.