Archive

From Wanted To Unwanted

You can have a product without a business, but you can’t have a business without a product. If you build a product that people want, a business will be born either from your loins or from some copycat’s. There’s no chicken and egg dilemma here. It’s simply, product-first and business-second. Ka-ching!

But wait, that’s not all! Let’s say you do get lucky and start a biniss around a “wanted” product that you built. To sustain your business, you gotta sustain your product. That means continuously maintaining it via the addition of new value-added features and the correction of customer-annoying defects.

Upon observing the deterioration of his original ArsDigita product under the so-called leadership of “new management”, Philip Greenspun said:

Once you have a product that nobody wants, it doesn’t matter how good your management team is. – Phil Greenspun (Founders At Work, Jessica Livingston)

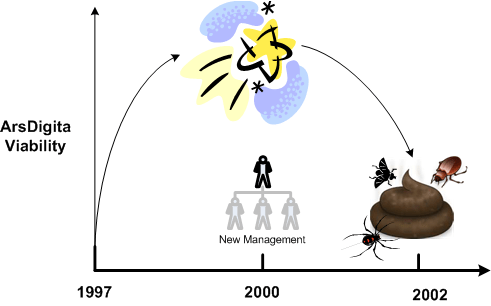

So, how does a “wanted” product morph into an “unwanted” product? Via neglect and indifference. That’s what happened to Phil’s baby when the vulture capitalists he hooked up with installed an incompetent “professional management team” to run ArsDigita (into the ground). By focusing on the superficial instead of the substance, the promotion instead of the maintenance, the company’s product, and then the company itself, went down hill fast:

ArsDigita grew out of the software that Greenspun wrote for managing photo.net, a popular photography site. He released the software under an open source license and was soon deluged by requests from big companies for custom features. He and some friends founded ArsDigita in 1997 to take on such consulting projects. In 2000, ArsDigita took $38 million from venture capitalists. Within weeks of the deal closing, conflict arose between the new investors and the founders. They marginalized and then fired most of the founders, who responded by retaking control of the company using a loophole the VCs had overlooked. The legal battle culminated in Greenspun’s being bought out, and a few months later the company crashed. ArsDigita was dissolved in 2002. – (Founders At Work, Jessica Livingston)

No Spin From Greenspun

Jessica Livingston interviews a boatload of founders (32 to be exact) of startup companies in her book “Founders At Work“. The most fascinating interview that I’ve read to date is with Phil Greenspun. It’s especially fascinating because it strongly reinforces “my belief system” that most corpo SCOLs are incompetent and most venture capitalists are obsessed with greed. You know how it is, relentlessly seeking out and amassing stories and evidence that irrefutably “prove” that you’re right while ignoring any and all disconfirming evidence to the contrary.

After reading the Livingston-Greenspun dialog, I was so giddy with ego-inflating joy that I wanted to copy and paste the entire interview into this post. However, I thought that would be too extravagant and probably a copyright law violation to boot. Here are some jucilicious fragments that prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that I’m absolutely right and anyone who disagrees with me is absolutely wrong. Hah Hah! Nyuk, nyuk, nyuk!

We talked to a headhunting firm, and the guy was candid with me and said, “Look, we can’t recruit a COO for you because anybody who is capable of doing that job for a company at your level would demand to be the CEO.” And I thought, “That’s kind of crazy. How could they be the CEO? They don’t know the business or the customers. How could we just plunk them down?” In retrospect, that was pretty good thinking; look at Microsoft: it took them 20 years to hand off from Bill Gates to Steve Ballmer. He needed 20 years of training to take that job. Jack Welch was at GE for 20 years before he became CEO. Sometimes it does work, but I think for these fragile little companies, just putting a generic manager at the top is oftentimes disastrous.

The guys on my Board had been employees all of their lives. You can’t turn an employee into a businessman. The employee only cares about making his boss happy. The customer might be unhappy and the shareholders are taking a beating, but if the boss is happy, the employee gets a raise.

Some of my cofounders and more experienced folks were also stretched pretty thin because of the growth. I thought, “We just need the insta-manager solution.” Which, in retrospect, is ridiculous. How could someone who didn’t know anything about the company, the customers, and the software be the CEO?

A lot of the traditional skills of a manager were kind of irrelevant when you only have two or three-person teams building something. So it was almost more like you were better off hiring a process control person or factory quality expert instead of a big executive type.

The CEO was a guy who had never been a CEO of any organization before, and he brought in his friend to be CFO. His buddy didn’t have an accounting degree and he was really bad with numbers. He couldn’t think with numbers, he couldn’t do a spreadsheet model accurately. That generated a lot of acrimony at the board meetings. I would say, “Things are going badly.” And he’d say, “Look at this beautiful spreadsheet. Look at these numbers; it’s going great.” In 5 minutes I had found ten fundamental errors in the assumptions of this spreadsheet, so I didn’t think it would be wise to use it to make business decisions. But they couldn’t see it. None of the other people on the board were engineers, so they thought, “Well, he’s the CFO, so let’s rely on his numbers.” Having inaccurate numbers kept people from making good decisions. They just thought I was a nasty and unpleasant person, criticizing this guy’s numbers, because they couldn’t see the errors. From an MIT School of Engineering standpoint, they were all innumerate.

Meanwhile, because these people didn’t know anything about the business, they were continuing to lose a lot of money. They hired a vice president of marketing who would come in at 10 a.m., leave at 3 p.m. to play basketball, and had no ideas. He wanted to change the company’s name. This was a product that was in use in 10,000 sites worldwide—so at least 10,000 programmers knew it as the ArsDigita Community System. There were thousands and thousands of people who had come to our face-to-face seminars. There were probably 100,000 people worldwide who knew of us, because it was all free. And he said, “We should change the company name because, when we hire these sales-people and they’re cold-calling customers, it will be hard for the customer to write down the name; they’ll have to spell it out.” And they did hire these professional salespeople to go around and harass potential customers, but they never really sold anything.