Archive

Line, Dot, Cone

My friend and mentor from afar (if you’ve looked around your local environment, there’s an incredible dearth of mentors from a-near), William L. Livingston, is about to hatch his fourth book: “Design For Prevention“. I’m happy to say that I’ve served as a reviewer and a source of feedback for D4P. I’m sad to say that it won’t become a New York Times bestseller because it’s one of those blasphemous books that goes against the grain and will be rejected/ignored by those it could help the most – institutional leaders.

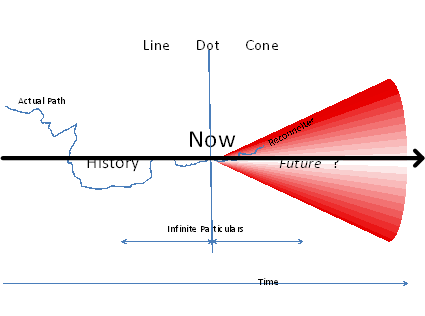

One of the graphics in DfP that I’ve fixated on is the “Line Dot Cone” drawing. As shown below, the path to “now” is not smooth and deterministic. It’s non-linear and quite haphazard. Likewise, the future holds an infinite cone of possibilities. The only way to narrow the cone of future uncertainty is to perform continuous reconnaissance via sensing/probing/simulating and then intelligently acting upon the knowledge gained from the effort, where intelligence = appropriate selection (W. Ross Ashby) and not academic knowlege.

CCH corpocracies don’t acknowledge the existence of the Line-Dot-Cone reality. It would undermine the carefully crafted illusion that the dudes in the penthouse have projected about their ability to make the future happen. In their fat heads, as the overlay below shows, progress always occurs linearly in accordance with their infallible control actions. Thus, no reconnaissance is needed and all will be well for as long as they rule the roost.

Ego Appeasement

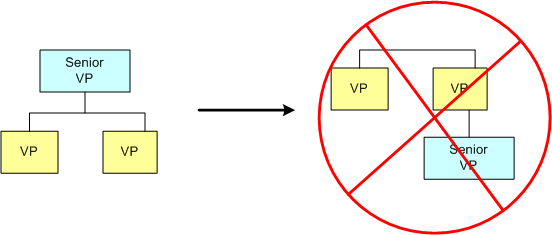

It’s funny how dysfunctional orgs will demand unquestioned loyalty from the masses in order to help the org grow and develop, but at the same time thwart that goal by appeasing egos to the detriment of the org as a whole. In defiance to what’s best for the community that they lead, top echelon leaders will not merge or disassemble org units if middle managers will have their egos bruised.

For example, if it makes economic sense to tuck or merge an obsolete unit run by a senior VP under a “regular” VP for the betterment of the whole org, the top dogs won’t do it out of “respect” for the titular system of privilege. God forbid that a senior VP report to a regular VP. It’s verboten in CCH-land. Another corpo faux pas is forming an org that may increase profitability but has a VP reporting to a lowly Director. Ain’t gonna happen.

Such is the power of titular hierarchies to thwart their own development.

Byzantine Labyrinth

During the birth and growth of dysfunctional CCHs, here is what happens:

- silos form and harden,

- a bewildering array of narrow specialist roles get continuously defined,

- layers of self-important and entitled RAPPERS emerge, and

- a byzantine labyrinth of processes and procedures are created by those in charge.

This not only happens under the “watchful eyes” of the head shed, but incredibly, those inside the shed-of-privilege are the chief proponents and instigators of all the added crap that slows down and frustrates the DICforce. Peter Drucker nailed it when he opined:

Ninety percent of what we call ‘management’ consists of making it difficult for people to get things done – Peter Drucker

On the other hand, T.S. Eliot also pegged it with:

“Half of the harm that is done in this world is due to people who want to feel important. They do not mean to do harm… They are absorbed in the endless struggle to think well of themselves.” – T. S. Eliot

Unscalable Orgs

My friend Byron Davies sent me a link to this 3 minute MIT Media Lab video in which associate Media Lab Director Andy Lippman challenges us to recognize four common flaws plaguing all of our institutions. Obtaining a new awareness and understanding of the plague is the first step toward meaningful redesign.

According to Lippman, the top four reasons for organizational decline are:

- They’re out of scale – they’ve grown too big to perform in accordance with their original design

- They’re monocultures – they all act the same

- They’re opaque – nobody from within or without understands how they freakin’ work

- They’ve lost their original mission – A summation of the previous three reasons.

Because of the pervasive institutional obsession for growth, Lippman seems to think that solving the scaling problem through the development of nested communities is the most promising strategy for halting the decline.

Nested Bureaucracies

By definition, ineffective bureaucracies (are there any effective ones?) consume more resources than they produce in equivalent value to their users/consumers. According to Russell Ackoff, the only way an ineffective bureaucracy can remain in place is by external subsidization that is totally disconnected with its performance. In other words, bureaucracies rely on clueless sugar daddies supplying them with operating budgets without regard to whether they are contributing more to “the whole” than they are withdrawing. Unchecked growth of internal bureaucracies siphons off profits and it can, like a cancer, kill the hosting org.

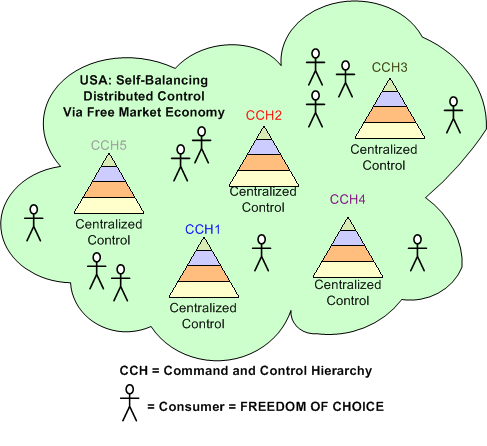

The figure below shows a simplistic bird’s eye view of an American economic system dominated by CCH bureaucracies. The irony in this situation is that even though the Corpo Granite Heads (CGH) in charge of the CCHs are staunch supporters of the distributed free market model which rewards value creation and punishes under-performance, they run their own orgs like the old Soviet Union. Ala GM and most huge government departments, they operate as centralized, nested bureaucracies where the sloth at the top trickles money down to the mini-bureaucracies below – without regard to value produced.

Bureaucracies, being what they are and seeking to survive at all costs, jump through all kinds of hoops to camouflage their worthlessness and keep the money flowing down from the heavens. Since the cabal at the top is too ignorant to recognize that it’s a bureaucracy in its own right, it’s an expert camouflage spinner to the corpocracy’s stakeholders (who gobble up the putrid camouflage with nary a whimper) and it sucks much more out of the corpo coffers than it adds value without being “discovered and held accountable”. In the worst nested bureaucracies, none of the groups in the hierarchy, from the top layer all the way down the tree to the bottom layer, produce enough value to offset their ravenous appetite for resources. They collapse under the weight of their own incompetence and then wonder WTF happened. From excellence to bankruptcy in 24 hours.

The really sad part is that before a bureaucracy auto-snaps into place, it wasn’t a bureaucracy in the first place. Everybody in the “startup” contributed more than they withdrew from the whole, and the excess value translated into external sales and internal profits. Like the boiled frog story, the transformation into a bureaucracy was slooow and undetectable to the CGHs in charge. Bummer.

The answer to this cycle of woe, according to Ackoff, is for the leaders in an org to operate the whole (including themselves) as a system of nested free markets, where each internal consumer of services gets to choose whether it will purchase needed services from internal groups, or external groups. Each internal group, including the formerly untouchable head shed, must operate as a measurable profit and loss center. Mr. Ackoff describes all the details of nested free market operation, including responses to many of the “it can’t work because of……” elite whiners, in his insightful book: Ackoff’s Best. Check it out, if you dare.

Accessible And Accessed

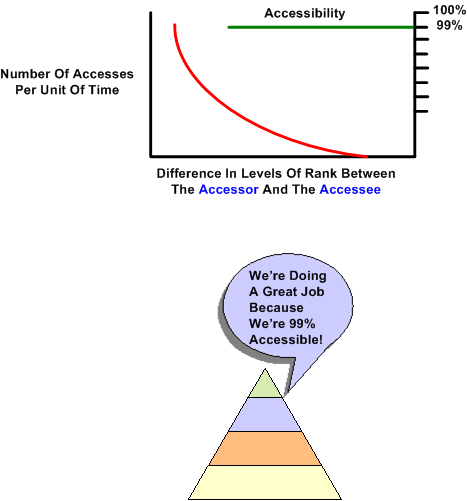

One of the metrics that a lot of corpo hierarchs assess themselves on is how accessible they are to their people. However, being accessible (textbook open door policy, walking the halls, e-mail, pseudo-mandated all hands meetings) doesn’t mean being accessed. For obvious reasons, they don’t measure themselves on this important metric, especially how frequently they are accessed (voluntarily and unsolicited) by their non-direct reports. In the vast majority of corpocracies, the number of accesses per unit of time goes down as the difference between caste levels of the accessor and accessee goes up. Just because that’s the way it’s always been doesn’t mean that’s the way it should or could be.

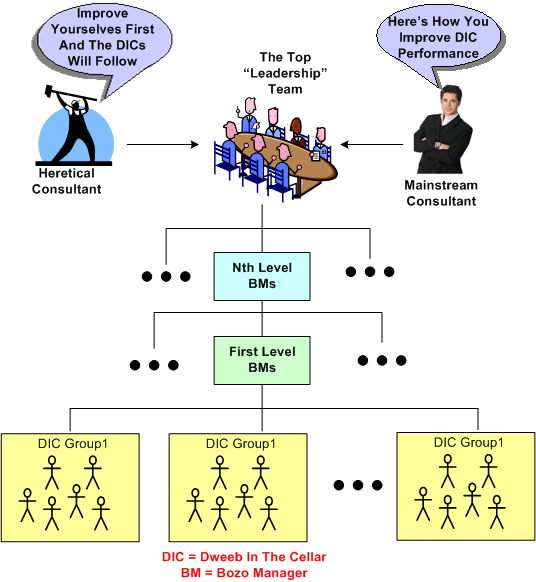

Management Gurus

Every student of management methods has heard of the blah, blah mainstream gurus like Prahalad, Charan, Christensen, Covey, Collins et al. How many of you have heard of Argyris, Mintzberg, Ackoff, Warfield, Ackoff, Beer, Livingston? You never hear of these dudes because they’re out on the lunatic fringe. They’re heretical, in-your-face realists who tell it like it is; which rubs CEOs and self-important top management teams the wrong way, of course. Thus, their work is ignored.

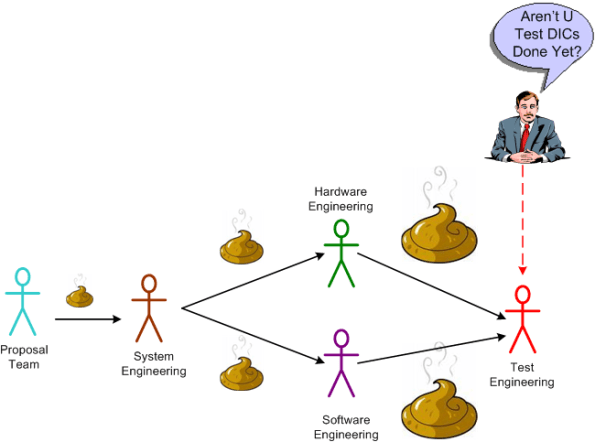

Poor Test Dudes

Out of all the types of DICs in a textbook CCH, the poor test dudes always have the roughest go of it. Out of necessity, they have mastered the art of nose pinching.

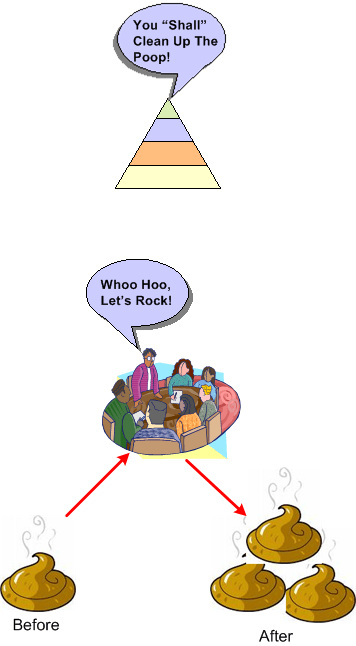

A Flurry Of Activity

It’s always fun to watch the initial stages of euphoria emerge and then disappear when a corpo-wide initiative that’s intended to improve performance is attempted. The anointed “design” team, which is almost always filled exclusively with managers and overhead personnel who conveniently won’t have to implement the behavioral changes that they poop out of the initiative themselves, starts out full of energy and bright ideas on how to solve the performance problem. After the kickoff, a resource-burning flurry of activity ensues, with meeting after meeting, discussion after discussion, and action item after action item being tossed left and right. When the money’s gone, the time’s gone, and the smoke clears, business returns to the same old, same old.

As a hypothetical example, assume that an initiative to institute a metrics program throughout the org has been mandated from the heavens. At best, after spending a ton of money and time working on the issue, the anointed design team generates a long list of complicated metrics that “someone else” is required to collect, analyze, and act upon. The team then declares victory and self-congratulatory pats on the back abound. At worst, the team debates the issue for a few meetings, conveniently forgets it, and then moves on to some other initiative – hoping that no one notices the useless camouflage that they left in their wake. Bummer.

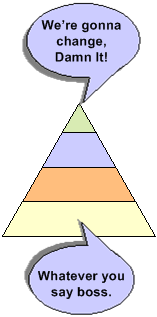

We Promise To Change, And We Really Mean It This Time

GM is a classic example of a toxic Command and Control Hierarchical (CCH) corpocracy. In this NY Times article, the newly anointed hierarchs and their spin doctors promise that “things will be different” in the future. Uh, OK. If you say so.

According to corpo insiders, here’s the way things were.

…employees were evaluated according to a “performance measurement process” that could fill a three-ring binder.

“We measured ourselves ten ways from Sunday,” he said. “But as soon as everything is important, nothing is important.”

Decisions were made, if at all, at a glacial pace, bogged down by endless committees, reports and reviews that astonished members of President Obama’s auto task force.

“Have we made some missteps? Yes,” said Susan Docherty, who last month was promoted to head of United States sales. “Are we going to slip back to our old ways? No.”

G.M.’s top executives prized consensus over debate, and rarely questioned its elaborate planning processes. A former G.M. executive and consultant, Rob Kleinbaum, said the culture emphasized past glories and current market share, rather than focusing on the future.

“Those values were driven from the top on down,” said Mr. Kleinbaum. “And anybody inside who protested that attitude was buried.”

In the old G.M., any changes to a product program would be reviewed by as many as 70 executives, often taking two months for a decision to wind its way through regional forums, then to a global committee, and finally to the all-powerful automotive products board.

“In the past, we might not have had the guts to bring it up,” said Mr. Reuss. “No one wanted to do anything wrong, or admit we needed to do a better job.”

In the past, G.M. rarely held back a product to add the extra touches that would improve its chances in a fiercely competitive market.

“If everybody is afraid to do anything, do we have a chance of winning?” Mr. Stephens said in one session last month.

The vice president would say, ‘I got here because I’m a better engineer than you, and now I’m going to tell you how bad a job you did.’ ”

The Aztek was half-car, half-van, and universally branded as one of the ugliest vehicles to ever hit the market. … but his job required him to defend it as if it were a thing of beauty.

Here’s what they’re doing to change their culture of fear, malaise, apathy, and mediocrity:

G.M.’s new chairman, Edward Whitacre Jr., and directors have prodded G.M. to cut layers of bureaucracy, slash its executive ranks by a third, and give broad, new responsibilities to a cadre of younger managers.

Replacing a binder full of job expectations with a one-page set of goals is just one sign of the fresh start, said Mr. Woychowski.

Mr. Lauckner came up with a new schedule that funneled all product decisions to weekly meetings of an executive committee run by Mr. Henderson and Thomas Stephens, the company’s vice chairman for product development.

Mr. Stephens has been leading meetings with staff members called “pride builders.” The goal, he said, was to increase the “emotional commitment” to building better cars and encourage people to speak their minds.

“But now we need to be open and transparent and trust each other, and be honest about our strengths and weaknesses.”

So, what do you think? Do you think that these “creative” CCH dissolving solutions and others like them will do the trick? Do you think they’ll pull it off? Is it time to invest in the “new” GM’s stock?