Archive

What Happened To Ross?

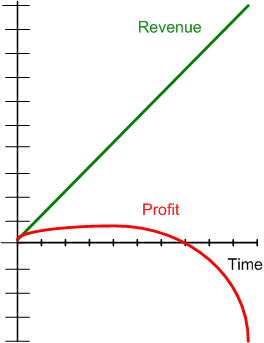

In the ideal case, an effectively led company increases both revenues and profits as it grows. The acquisition of business opportunities grows the revenues, and the execution of the acquired business grows the profits. It is as simple as that (I think?).

ROS (Return On Sales) is a common measure of profitability. It’s the amount of profit (or loss) that remains when the cost to execute some acquired business is subtracted from the revenue generated by the business. ROS is expressed as a percentage of revenue and the change in ROS over time is one indicator of a company’s efficiency.

The figure below shows the financial performance of a hypothetical company over a 10 year time frame. In this example, revenues grew 100% each year and the ROS was skillfully maintained at 50% throughout the 10 year period of performance. Steady maintenance of the ROS is “skillful” because as a company grows, more cost-incurring bureaucrats and narrow-skilled specialists tend to get added to manage the growing revenue stream (or to build self-serving empires of importance that take more from the org than they contribute?).

For comparison, the figure below shows the performance of a poorly led company over a 10 year operating period. In this case the company started out with a stellar 50% ROS, but it deteriorated by 10% each subsequent year. Bummer.

So, what happened to ROS? Who was asleep at the wheel? Uh, the executive leadership of course. Execution performance suffered for one or (more likely) many reasons. No, or ineffective, actions like:

- failing to continuously train the workforce to keep them current and to teach them how to be more productive,

- remaining stationary and inactive when development and production workers communicated ground-zero execution problems,

- standing on the sidelines as newly added “important ” bureaucrats and managers piled on more and more rules, procedures, and process constraints (of dubious added-value) in order to maintain an illusion of control,

- hiring more and more narrow and vertically skilled specialists that increased the bucket brigade delays between transforming raw inputs into value-added outputs,

may have been the cause for the poor performance. Then again, maybe not. What other and different reasons can you conjure up for explaining the poor execution performance of the company?

Business Acquisition And Execution

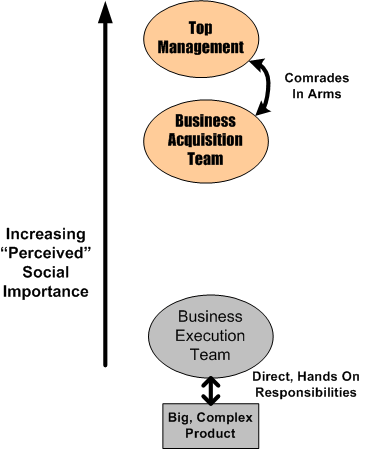

To become and maintain a successful business, a company must both acquire and efficiently execute ongoing chunks of business. When top management values both of these critical work activities equally, then all is well. When they value one over the other, and in my business domain it’s always business acquisition that’s shown preferential treatment, then mediocrity reigns.

How do you know when top management is one sided? It’s easy, just look around. Who gets the single offices and single cubes? Who gets the bigger salaries? Who do the executives give way more face time to?

Business acquisition is glamorous and difficult, but in comparison, business execution is dirty, messy, and down right hard. When an acquisition team submits a proposal to a customer after a long and arduous courting period, it’s party time, and rightfully so. However, and this is key, the proposal doesn’t “have to work”. Products “have to work”, or else….

If a proposal is rejected and fails to acquire a chunk of business, then it’s usually because a competitor has offered up a similar or superior product for a lower price and/or a faster delivery time. The loser washes his hands clean and then just moves on to the next opportunity. It’s done and over with, kaput.

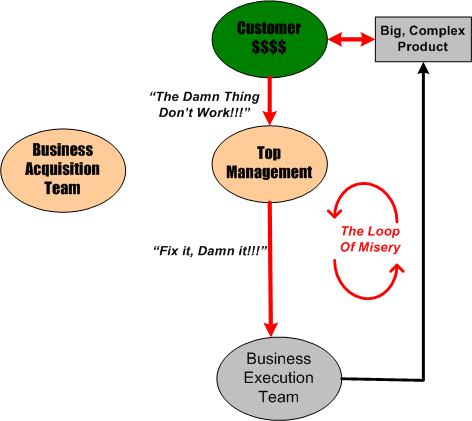

When a big, complex, and software-intensive product repeatedly and frequently fails in a customer’s day to day use of it, then continuous stress and pressure is placed on the execution team for what could be quite a long and sustained period of time. Until the execution team, usually through heroic acts of team sacrifice, makes the product behavior and performance “acceptable” to the customer, the two step chain of events is as follows: the customer pressures top management, and top management pressures the execution team. The loop of misery has been ignited. Notice that the acquisition team does not participate in the fun. In the worst case, the acquisition team merges with the top management team to apply greater pressure on the execution team.

Don’t be a stupid arse like me. If you’re given the choice between participating on an acquisition team or an execution team, choose the acquisition team 🙂

Round And Round We Go

Engineering Councils, Master Engineering Groups, Centers of Excellence, yada-yada-yada. Has your company repeatedly formed and dissolved elite groups like these over the years? The purpose of sanctioning these groups is always well-intentioned, but always doomed. Why are they doomed? Because:

- they are always underfunded and, at the first hint of corpo financial stress, they are abandoned because they are an overhead expense group that doesn’t create or add value.

- all of the sitting members have real day jobs that need to get done in order to put money in the corpo coffers and food on the table.

- they don’t actively solicit input from the people who have to operate by their decisions – if they ever make any decisions and produce non-verbal output at all.

- they ignore input from non-members when they do get it – losing credibility and respect in the process.

- they never agree to a systematic method of making decisions when they are formed.

- they spend all their time in philosophical debates, with each elite member trying show how smart he/she is.

I could probably make up some more excuses for the repeated cyclical failure of elite councils, but I’ll leave it as an exercise for you, dear reader, to add your own reasons to the list. Feel free to add your own thoughts on this via the comments section.

Each time the elite council idea is recycled, nobody seems to remember the failures of the past and the same unproductive group behavior emerges. Everybody but the BOTG (Boots On The Ground) innocently thinks that this time it will be “different”. I’ve participated in these elite groups in the past, but from now on, I’ll always respectfully decline membership when asked. The last time I was asked, I declined to sit on one of these boards (that’s exactly what they do – just sit) . However, I offered up my services to work on any specific and funded task that the group deemed important. Unsurprisingly, nobody has taken me up on my offer. Bummer :^)

So how can the elite council idea be successful and add value to an org? Just invert the reasons-for-failure list above. Even if you do manage to change the context from disabling to enabling, it still might not work but, at least it will have a chance.